Introduction

In February 2022 the Sprits Business magazine published a list of the 2022 Rum and Cachaca Masters competition awards (also referred to as the Global Spirits Masters’ Awards), which I would strongly recommend you read (it’s not a long article and the list of awardees is at the bottom).

Normally I pass by spirits competitions without comment (and occasionally with indifference), since I think they have more value as marketing tools; they may possibly alert me to something I might want to check out and review one day, though. So when first scanning the list of the medal winners for these “Masters” I just sighed and – almost – moved on.

But the more I looked a that medals list, the more I saw how this one awards extravaganza was being repeated and shared online (once by Forbes Magazine, no less) the more I realised that there was far more wrong with the whole business than that brief first read had suggested.

In brief: here was a competition stratified into 24 different categories into which 222 “rums” were sorted (a list of the categories is given below this article); and evaluated by 15 judges divided into five panels (what the panels were for is unclear), only three names of which I recognized.

Within these bare-bones facts lurked what I gradually began to see as endemic problems not limited to just this competition but which it exemplified in a fashion more obvious than before. And whether they considered them or not, they have impacts way beyond their ephemeral online life.

Part 1 – The Big Issues

One of my main concerns here, is the business of using price as a determinant in some categories — it was used inconsistently, for some but not all entrants, and for the first time in any major competition of recent note (as far as I am aware). This strikes me as a completely spurious subcategory, given the inevitable variation in the cost of a rum around the world (even within the same country and if you are going to use the UK as your base case, don’t call the competition “Global”). Price points are not, of course, accepted by anyone as a rigorous standard, and I certainly would never rank my purchases or ratings according to such a criterion. It doesn’t stop there either: these pound-denominated values were related to equally problematic categories of “premium”, “super premium” and “ultra premium” categories. I mean, whose wallet is being consulted here, really? One person’s budget may suggest a super premium starts at a fifty quid, not £26, while another’s might be a hundred. Though, as far as I am concerned, the twenty-six-pound price point is insultingly low for anything boasting the cachet of a “premium” of any sort, and does nothing but cheapen the word.

As if to add insult to injury, it was decided (as had also been the case in the 2021 Competition) that colour could be used as a category marker, when it has been shown for many years that it is useless as a barometer of grouping like with like. I want to repeat this loud and clear: “Gold” and “Dark” in particular have exactly zero meaning and zero standing as classifiers, and even “White” has its issues, especially in the last five years. But this was evidently not enough, because having now used it and combined colour coding with the equally meaningless “premium” terms, rums were also divided up into age bands … but this was in yet another set of categories, not the coloured, priced or premiumised categories that had already been established. Clearly then, dark and gold rums that are premium can’t also have ages, and dark or gold rums that are aged can’t be any kind of premium.

A point of lesser importance to some but of greater value to others (I’m one of the latter), is that unless we know how many rums were in a competition, and within that competition by category, and not just a list of the winners, we can’t gauge its usefulness because we have no basis for comparison. And even looking at the list and the narrative itself, I felt uneasy – because okay, there were 222 entrants…but of these, a staggering 189 of them, more than 85%, were awarded medals (I hesitate to say “won” because that’s just demeaning the word). This really defeats the purpose of a competition, because it is simply getting a medal for showing up. To be honest, after disbelievingly checking that stat (twice), what I really wanted to know was more about the 33 losers than any of the winners. The value of any medal is conferred by its exclusivity, not by how many others are sharing the podium. Just think about it…10 silver medals awarded to spiced entrants, and another 12 silvers for flavoured rums? No sir.

I appreciate that by now you may be feeling a little punch drunk. Sorry. But it doesn’t end there.

Consider the title of the competition: “Rum & Cachaca Masters” with a category cachacas combined with cane spirits . With that kind of title, you would expect a lot of Brazilian cachacas in the lineup, right? Loads of cane juice agricole-style rhums? Wrong. Four cachacas copped a score, three hailing from one company. Excuse me? Even in the wasteland of Toronto or nominally dry states south of 49, one can pick up more than that, and with Brazil having hundreds and thousands of them, is this really the best that could be found to rate? Even if all the other 33 non-winners of the entire competition were cachacas, a total of 37 is not useful as a barometer of the quality that’s out there to judge.

Lastly there are the non-rums or “not-quite-rums” which are the flavoured variants. A spiced rum being part of this kind of mashup is, I suppose, tolerable, even though I personally disagree (because I do not believe spiced rums have any place in this competition as “rums” and should have their own rankings independent of non-adulterated fare). But to then have added categories of “flavoured”, “flavoured overproof”, “spirit drink” and “flavoured spirit drink” just adds categories for the sake of having them, conflates them with real rums, and mangles any kind of understanding people might possibly have of what rum truly is.

(Lest you think it’s all bad, at least they didn’t confuse unaged agricoles rhums with their conception of white rums and only one rum (the CDI Jamaica Navy Strength) was in more than one category. I assure you, I am grateful for that).

Part 2 – Origins

To some extent I blame Spirits Business itself for this, though the issue is really about poor award administration, and poorer education and knowledge of the field of rums, as well as preconceptions about them made that really seem to be as unkillable as Voldemort.

I don’t doubt that the editorial staff, organisers and judges had their hearts in the right place, wanted to rank things honestly and by their own lights; and just to get a couple hundred entrants into the room to be judged at all must have taken some doing. I’ve heard the panels were set up to be independent, the tastings were blind, all of which is nice – though it’s sort of a least common denominator for such things.

But I believe that the categorizations – by far my biggest concern – was not chosen or defined by people in the rumworld or by anyone who really knew rum (or cared), because no reputable rum connoisseur, blogger, influencer, or even halfway involved enthusiast would ever chose such stratifications. None. They would have laughed and pointed the organisers to the Cates method, the Gargano system, or any of the other hybrid versions of these that are used by rum festivals around the world for many years (Cates and Gargano are not universally accepted, though they are the best known and among the most popular).

Also, I think the selection of the judges was poor, including SB’s own editorial staff, the magazine’s writers and one person who was into spirits for five years and mostly dealing with gin, not rum. This sounds fine on paper – a balanced set of experts from across the spectrum – but when taken to its logical outcome, it falls down flat.

Also, I think the selection of the judges was poor, including SB’s own editorial staff, the magazine’s writers and one person who was into spirits for five years and mostly dealing with gin, not rum. This sounds fine on paper – a balanced set of experts from across the spectrum – but when taken to its logical outcome, it falls down flat.

For some perspective, let me put it this way: everyone knows I am into rum and have been for over a decade. I do appreciate whiskies and have a smattering of knowledge about wine and gin and vodka and even cocktails – but would you trust me to knowledgeably and appropriately rate and rank and judge any of those drinks in a competition? Of course not — you would be right not to want me there, and I would be wrong to accept. In short, much as the judges were enthusiastic and dedicated and honest about their evaluations, I question the knowledge base when their love is so widely dispersed among other spirits and not really rum at all (except for three of them, who I know from experience focus their attentions there).

And all is done this by a self-professed professional industry publication, Spirits Business, which touts itself as “…the only dedicated international spirits magazine and website in the world” and revels in how its “varied and insightful features and analysis cover a broad range of topics” and boasts of “our team of award-winning journalists”. This is all well and good, and I do appreciate the breadth of knowledge of the team: but alongside that is perhaps an issue of trying too hard, and doing too much with too few (or too many) resources in the running of all these various such competitions for whiskey, gin, vodka etc etc without actually getting people who know their subject intimately doing the set up, judging and awarding.

Part 3 – Recommendations

So, let’s sum up. This competition is too poorly categorised to be taken seriously, the sample set is too small to be meaningful, too few brands and companies were represented to deserve the title “Global” and too many medals are handed out too generously to reflect real quality and value of their award. They may have thought they were promoting rum, showing off the best of what is out there – what they have in fact accomplished is to denigrate the category and confuse the consumers who take this stuff seriously, or who want to.

But fair is fair, if I bitch and moan about this kind of thing, well, what are my better ideas to fix it, do better?

Rum is problematic not in that it lacks categorization, but that it has too many variations to be neatly summarised in just a few, and it doesn’t help that no overarching body exists to even set voluntary classification standards. If was up to me I’d do what SB did with whiskies and have a separate competition for cane juice and molasses based rums, another for spiced and flavoured stuff, a category for multi-styled blends, and then stratify within those broad bands. Or, I’d hang my hat on either the Cate or Gargano system and proselytise for that to be accepted and used by others. But no way would I allow mealy-mouthed, wishy-washy, undetermined, undefined and unstandardized nonsense to be used.

Also, a minor point perhaps: I would find a way to dispense with the entry fees as far as possible because this just discourages entrants and reduces the numbers. One of the weaknesses of this and other competitions is that only what gets entered gets judged, and producers have to pay for each item they submit to be evaluated. A quick calculation shows that to bring five rums into this competition (not that many companies bothered) costs a thousand pounds . Now, mid-sized to large companies have no issues with that, but it’s hardly likely some small outfit will bother when they can do so much better at rum festivals where consumers actually get to taste, and journos and bloggers pay more attention. Maybe it’s wishful thinking to expect fees to be eliminated but I do argue they discourage candidates, encourage a medal-extravaganza by the organizers so the fees keep flowing, and if they can’t be done away with, at least they should be kept really really low to encourage maximum participation, and be bolstered by a “Contestant of the XYZ Competition” sticker / logo that can be used as a marketing tool if it doesn’t get a “Medal Winner” tag.

Lastly, I’d really try to rope in some judges who are well known and respected in the community from which the drinks originate. Getting a bunch of whisky anoraks, wine experts and spirits lovers, no matter how well-intentioned and broad-based, is not the best way forward here. Ditto for editors and newsies who take the entire field of global spirits as their fief, or those whose expertise is not in rum but in gin, wine, scotch, vodka or what have you. No doubt they bring good tasting chops to the table, but really, they are hands down losers when they come up against a real rum aficionado who knows what she’s looking for and what to experience.

Part 4 – Implications

So why did I write this piece? Normally I don’t get involved with this kind of thing because aside from others regarding the lists of awardees as useful for their own reasons, it makes me come off like some grumpy and crotchety old fart feigning intellectual pomposity (like Sir Scrotimus always was). The reason I chose to do so on this occasion was because too many things were out to lunch here, and the Forbes repost / reshare – with a headline of “The Wold’s Best Rums According to the Global Spirits Masters” really disturbed me (as did some of the medal winners’ unseemly crowing about how well they did, when they really didn’t). I was reminded forcibly of a comment I had written on Reddit about a HipLatina faux-journalistic hagiography of Bacardi, where my final observation was “… [it asks]…to be taken seriously as a sort of objective recounter of real history and factual information, and fails at both — and since people will read it and some will believe it, it’s best to get the objections and criticisms right out there, right now.”

That’s it, really. Not so much that the issues exist, but that knowledgeable folks keep repeating the same old tropes without correction, and that others will not know any better and accept it; that people will believe the veracity and usefulness of the exercise without critical inquiry. They will see the awards as some kind of real arbiter of agreed upon quality using formal standards of evaluation, when neither is the case. What these carelessly awarded medal-extravaganzas do is confuse and make people continue to dismiss rum as some kind of good-time drink lacking in credibility that still can’t get its act together. “They can’t even get their definitions and categories in order,” you can almost sense a whisky anorak sniff disdainfully as he buries his beak in a Bowmore.

So yes, I feel so strongly about the matter and I doubt I’m alone in this: after all the years of publicly available rum fests, deeply informative master classes, of aficionados writing about distillery tours (given or taken), gallons of digital ink spilled in writing educational pieces, non fiction pieces, reviews, backgrounders and deep dives into the world of rum, all this is so easily undone by a single awards show done on the quick and on the cheap without serious thought.

Awards competitions are taken seriously, and many of those reading about them will presume that the medals gained represent a real cross-section of the rumworld and its best rums. My contention is that this is simply not true in this case and it is allowing misinformation to creep into the minds of the up and coming next generation. Organizers of such competitions should take the responsibilities of what they are doing more seriously and understand the impact they have on the perceptions and knowledge of their readers. Anything less is an abdication of their duty of care to us as consumers and all those who are now coming into the field.

At least, that’s the way I see it.

Other Notes

- Some of the comments I make here are also incorporated into a similar post on reasons to beware of lists and not to accept them uncritically. It’s a good companion piece.

- The categories were as follows

-

- White Rum – Standard (£0‐£15)

- White Rum – Premium (£16‐£20)

- White Rum – Ultra Premium (£31+)

- White Overproof

- Gold Rum – Premium (£0‐£25)

- Gold Rum – Super Premium (£26‐£40)

- Gold Rum – Ultra Premium (£40+)

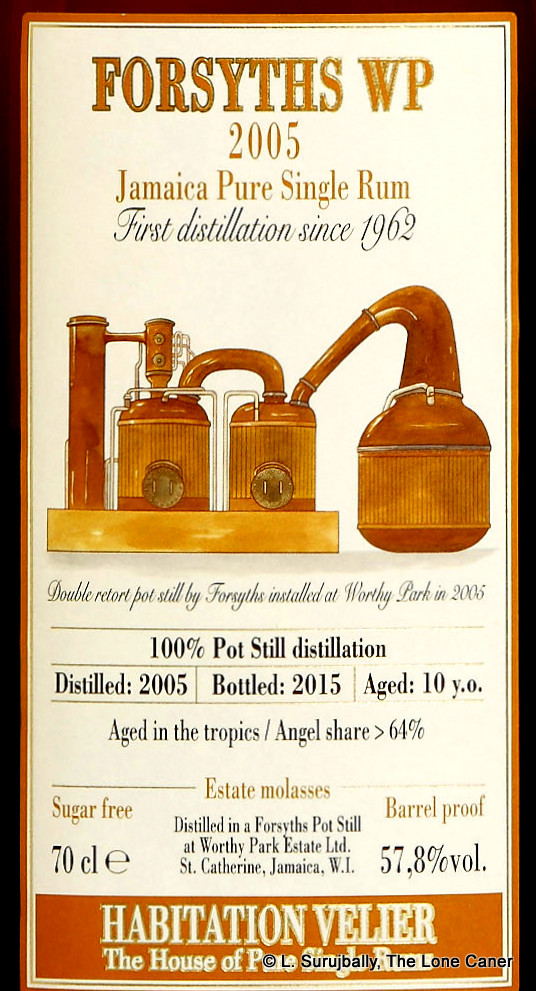

- Gold Rum – Aged up to 7 years

- Gold Rum – Aged 8‐12 years

- Dark Rum – Premium (£0‐£25)

- Dark Rum – Super Premium (£26‐£40)

- Dark Rum – Ultra Premium (£40+)

- Dark Rum – Aged up to 7 years

- Dark Rum – Aged 7 to 12 years

- Dark Rum – Aged over 13 years

- Dark Rum – Overproof

- Agricole Rhum

- Spiced

- Cane Spirit/Cachaça

- Flavoured Rum

- Flavoured Overproof

- Spirit Drink (up to 37.5% ABV)

- Flavoured Spirit Drink (up to 37.5% ABV)

- Rum Liqueurs

Rum and rhum aficionados are no strangers to Depaz, the distillery on Martinique now owned by Bardinet-La Martiniquaise. The sugar factory and (later) distillery had once been a family operation — the Depaz family from Livorno in Italy had been part of Martinique society since the 1700s — and was in existence even before its destruction by the eruption of Mt. Pelee in 1902. The estate’s modern history can truly be said to have begun with the reconstruction of the distillery in 1917; their immediate success at rum-making could be inferred from their winning of medals at the Marseille expos of 1922, 1927 and 1931, at a time when French island rhums were hardly very well known (even Bally only started making the good stuff around 1924). In 1989 the head of the family at the time, André Depaz, allowed a long time customer and distributor, the Bardinet Group, to take over Depaz, and in 1993 La Martiniquaise, another major spirits conglomerate who already owned Dillon, bought a controlling interest in Bardinet, and so remains the current owner.

Rum and rhum aficionados are no strangers to Depaz, the distillery on Martinique now owned by Bardinet-La Martiniquaise. The sugar factory and (later) distillery had once been a family operation — the Depaz family from Livorno in Italy had been part of Martinique society since the 1700s — and was in existence even before its destruction by the eruption of Mt. Pelee in 1902. The estate’s modern history can truly be said to have begun with the reconstruction of the distillery in 1917; their immediate success at rum-making could be inferred from their winning of medals at the Marseille expos of 1922, 1927 and 1931, at a time when French island rhums were hardly very well known (even Bally only started making the good stuff around 1924). In 1989 the head of the family at the time, André Depaz, allowed a long time customer and distributor, the Bardinet Group, to take over Depaz, and in 1993 La Martiniquaise, another major spirits conglomerate who already owned Dillon, bought a controlling interest in Bardinet, and so remains the current owner. That’s quite an intro from a rhum positioned as entry level, not costing too much, and quite young. Admittedly, the palate is not quite up to that level, but it’s not too shabby either: it presents a bit rough and sharp and spicy at the beginning, until it settles down, and then it becomes softer and warmer, like a scratchy old blanket you use on the sofa while watching TV. Sweet caramel, coconut shavings, vanilla, sugar cane juice, pears, apples, very ripe cherries and black grapes, are all noticeable right bout of the gate. The edges have not been entirely rounded off with some further ageing or blending, so much of the young and frisky nature of the rhum comes through, like a half-grown long-haired mutt that hasn’t quite adjusted to its strength. The finish is sharpish, medium long, mostly sugar water, citrus, herbs, toffee, some fruits and a light hint of lemon grass.

That’s quite an intro from a rhum positioned as entry level, not costing too much, and quite young. Admittedly, the palate is not quite up to that level, but it’s not too shabby either: it presents a bit rough and sharp and spicy at the beginning, until it settles down, and then it becomes softer and warmer, like a scratchy old blanket you use on the sofa while watching TV. Sweet caramel, coconut shavings, vanilla, sugar cane juice, pears, apples, very ripe cherries and black grapes, are all noticeable right bout of the gate. The edges have not been entirely rounded off with some further ageing or blending, so much of the young and frisky nature of the rhum comes through, like a half-grown long-haired mutt that hasn’t quite adjusted to its strength. The finish is sharpish, medium long, mostly sugar water, citrus, herbs, toffee, some fruits and a light hint of lemon grass.