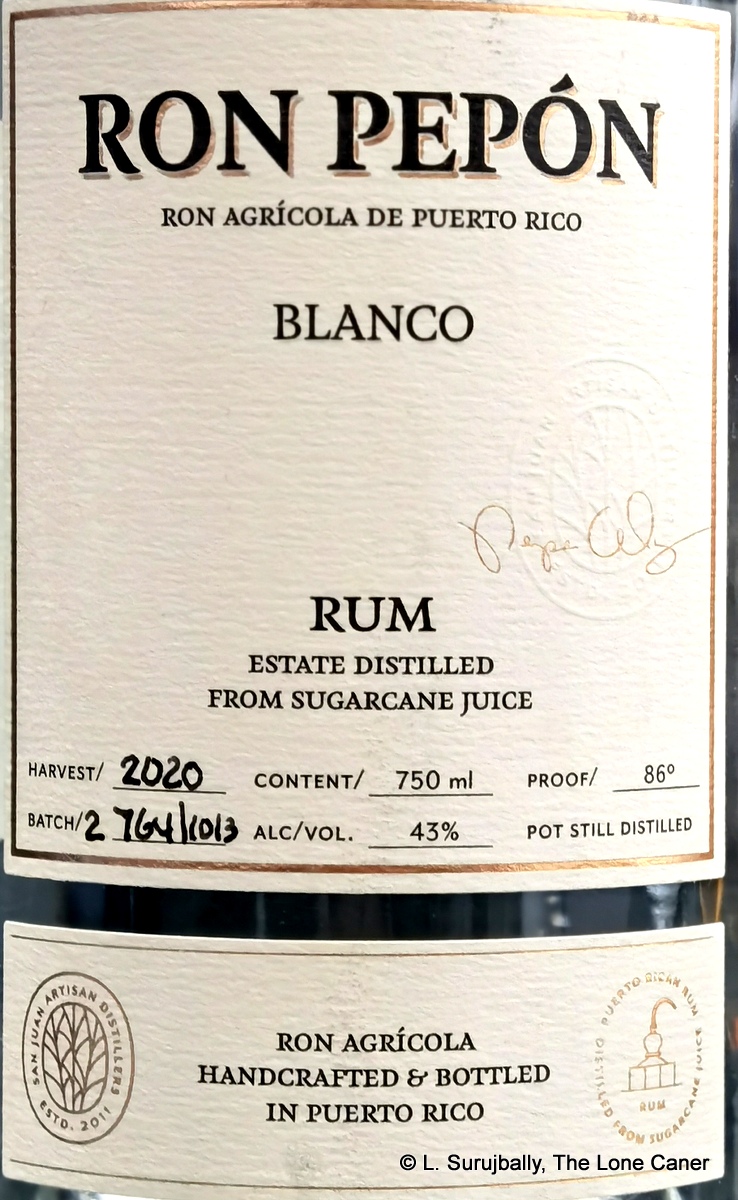

The stats by themselves are enough to make a committed rum geek shed a happy tear. It’s from a new distillery in the Caribbean, committed to making artisanal rum from sugar cane it grows itself. It’s pot still distillation: and not just any pot stills, but the charentais cognac stills that Moet Hennesy sold after abandoning their grandiose project to make rums in Trinidad with the aborted Ten Cane brand. Cane juice agricole style rums. Ageing in ex Bourbon casks for between two and three years. 43% ABV, so more than standard proof. No additives. I mean, you read all that, and how can you not be enthused? This is the horse on which French islands and Asian micro-distilleries have ridden to fame and fortune.

And yet, San Juan Artisanal’s Ron Pepón Añejo, Puerto Rico’s first agricole style cane juice rum, is somewhat of a letdown, presenting a lacklustre sort of profile that’s too shy to appeal to the geek squad, not distinctive enough to make it with the cocktail crowd and a hard sell to the majority of drinkers who have quite different ideas as to how both an agricola or a Latin style rum should taste. At best one can say it’s a decent enough starter-kit rum for those who want to dip their toes into cane juice rum (or ron) waters without being challenged by something as off the reservation as, oh, the Sajous. That’s not exactly a ringing endorsement

Consider the profile: the nose opens with vanilla, some watery but piquant fruits (pears, watermelon, overripe Thai mangoes), plus unsweetened yoghurt, some salt and pepper. One can discern dates, some figs and a faint metallic iodine and herbal tincture, but let’s be honest, it’s slim pickings to smell. The aromas are faint and very light, lacking some of the crisp assertiveness of an unaged agricole while not being aged enough to get any kind of real boost from the barrels.

This same issue is more noticeable when sipped. There really is not a whole lot going on here, even after one senses vanilla, cinnamon, bitter coffee grounds, mixed in with brine, olives, some iodine, figs and sweet smoky paprika. It’s not that there isn’t something there, it’s just too subtle to make a statement fort itself, and the finish is just disappointing, even if it does lead to a slightly more vegetal, sweet and vanilla lading close. It’s too short and too light, like Bacardis from the old days, which revelled in their anonymity as if it were a badge of honour.

This same issue is more noticeable when sipped. There really is not a whole lot going on here, even after one senses vanilla, cinnamon, bitter coffee grounds, mixed in with brine, olives, some iodine, figs and sweet smoky paprika. It’s not that there isn’t something there, it’s just too subtle to make a statement fort itself, and the finish is just disappointing, even if it does lead to a slightly more vegetal, sweet and vanilla lading close. It’s too short and too light, like Bacardis from the old days, which revelled in their anonymity as if it were a badge of honour.

It gives me no real pleasure to mark down a rum made by a bunch of people who work with passion, created a distillery from scratch, and seem to have really tried to come up with something new and interesting (see bio below). And I’m not the only one: a couple of years back LifoAccountant’s observations on the /r/rum subreddit bemoaned several of the same points I do here, and he gave it a rather sub-par 4/10. Almost no other non-marketing reviews exist, so of course there may be others who take the opposite view, that the rum is excellent, and I completely respect that. I just haven’t found any.

Anyway: for now, for me, it’s not good enough to shower it with encomiums. If it’s any consolation, I think any small new distillery that has such interesting equipment and source material and desire to go places, can’t help but succeed in the long term…and so I would chalk this one up to them still finding their rum legs. Because I don’t think they’ll stay in the kiddie pool for long — there’s too much going for them, for me to define or dismiss the entire brand because of one lone rum in their stable for which I didn’t care overmuch.

(#1062)(78/100) ⭐⭐⭐

Company Bio

San Juan Artisan Distillers is one of the new wave of Puerto Rican companies that seeks to muscle in on the long held territory of the mastodons of that island’s rum scene: Bacardi and Serralles. And while others have mostly gone from rum drinking to starting a distillery, a far more economic rationale was the inception of Pepe Álvarez’s project – his landscape and grass business went belly up when the recession of 2008 hit, coupled with US tax incentives for establishing businesses in PR expiring.

Since he was clearly too young to retire, Álvarez looked around and realized that his experience with grass and a 14 acre farm that had been acquired in 1991 which had grown to about 70 acres by now, offered an opportunity to bootstrap both into something unique to the island: rum made directly from sugar cane juice, not molasses. Starting the new company around 2012. he managed to find an investment from the Puerto Rican government, which paid for the irrigation system, tilling equipment, sugarcane seeds and the purchase of the mill. In so doing Alvarez sourced a German made Arnold Holstein pot still, and when the two charentais pot stills from Trinidad became available after Moet Hennessy pulled out of the Ten Cane project, he snapped those up too, and to back them up, he started his own cane fields, since commercial sugar cane growing in the island was a discontinued industry.

And this wasn’t all: his son Jose joined the company after getting his civil engineering degree, and Luis Planas the former master blender of Bacardi (now working for Ron de Barrellito) was asked to consult. As if that kind of horsepower was not enough, Frank Ward (ex-Managing Director at Mount Gay) provided advice on consult.

Initially the idea was to produce an agricola-style series of rums, to be released around 2017, at which point Hurricane Maria decided to derail that plan, demolished all the cane fields and left the island without power for almost a year. Undeterred, Alvarez used stocks he sourced from the Dominican Republic to make a series of fruit-infused rums with the brand name of “Tresclavos” (which, for those with memories of 1423’s unfortunately named sub-brand is not a combination of “Tres” and “esclavos” but “tres clavos” — ‘three nails’). These were well received and have become island staples, which allowed the fledgling company to weather the destruction of the fields so well that small batches of the new Ron Pepon were ready to go by 2018 with other stocks being laid down to age.

The global pandemic impacted the company as much as any other but has managed to come out the other side, and in 2022 had both an unaged white rum and a 30-month or so aged variant to present, which started selling stateside and appearing in Europe. So far the brand is not a huge seller or a famed name, but its reputation is starting to be known.

The place is experiencing growth — they now employ a staff of about six, built a visitor’s centre, have those amazing pot stills, still make only cane juice rum and various personages give them visibility (my friends from the Rumcast interviewed them in October 2022 as part of their Puerto Rican distillery roundup); and there have been several new stories abut them. It’s just a matter of time before they attain greater visibility and greater fame, and expand that series of rums they make. It’ll be worth waiting for, I think.

Other notes

- “Pepón” stands for “Old Pepe” and is a nod to Alvarez’s father, also named Pepe.

- My thanks to Jazz and Indy Anand of Skylark in London, in whose convivial company I tried this rum after filching it from their stocks. I don’t have “crash and pass out under the sink” privileges in Indy’s place: however, free access to the shelves of rum in every room more than makes up for that. Thanks and kudos as always, guys.