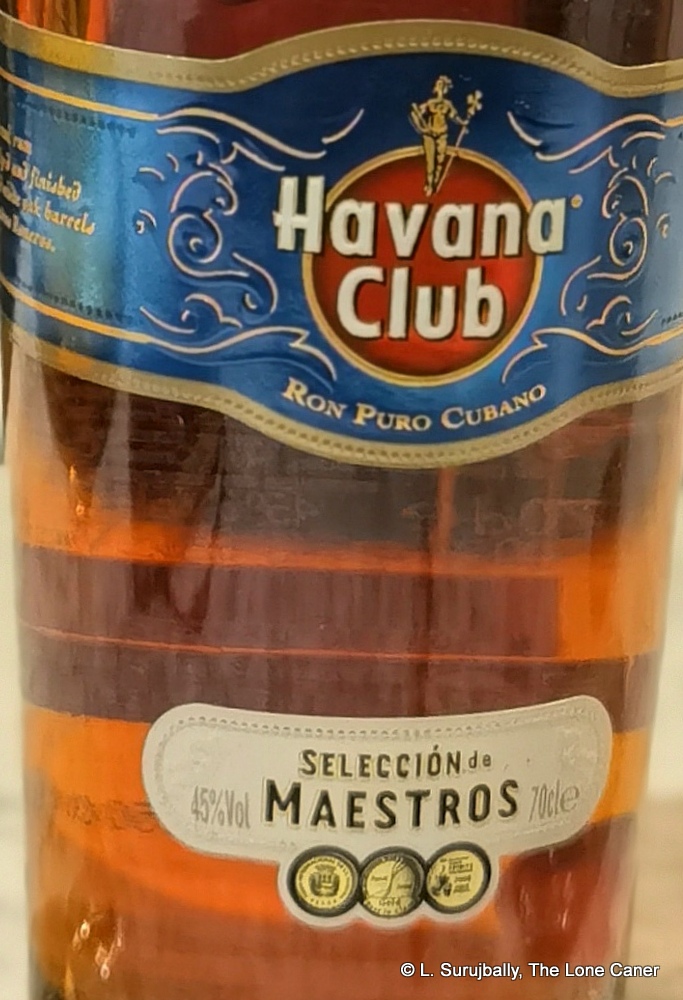

There are several worthy candidates for the claim of being the first one from Cuba. Havana Club 7 YO has been a really strong contender based on ubiquity and price, and the Santiago de Cuba 12 YO was also in the running for the same reasons. When one considers that the core criteria of the series is the Three ‘A’s – Affordability, Approachability and Availability – it would seem a slam dunk to say the HC-7 should get pride of place. Even the Havana Club 3 YO has had its adherents, though eventually I eliminated it based on several tastings and for its focus in the mixing circuit rather than it worth as a sipper. But the moment, there are several reasons why I feel the Selección de Maestros gets the nod for the first Cuban rum instead of the obvious choice, and ask you to walk with me on this one.

To begin with, it almost equals the HC7 in availability: over the last ten years I have travelled frequently and found the Selección in just about every airport and bar and spirits shop which I have passed through. Though America’s futile Cuban embargo remains in place after fifty years of failure, one can now bring rums from Cuba into the country as an individual, and it is gradually becoming known as one of the premiere Cuban rums, and classed as a premium product there and elsewhere. Since becoming widely available in the UK and Europe and elsewhere in the mid 2010s when it replaced its predecessor the Havana Club Barrel Proof (which I thought was really good as well), it has made a reputation for itself as one of the best Cuban rums outside of the special and limited editions premiums. There is hardly a discussion about Cuba’s best rums that doesn’t bring it up.

Initially the rum surprises with its restraint. At 45% ABV one expects somewhat more bite and aggressiveness on the nose (especially first thing in the morning), yet overall it is calm and unhurried, and as firm a no-nonsense nanny waking up the kids. It smells of sweet butterscotch, vanilla, some lime leaves and light breakfast spices. It retains a clean and crisp profile, redolent of olives, a slight bitter saltiness of old leather, and traces of molasses, caramel and brown sugar, together with a touch of coffee grounds.

Most reviewers who have run the rum through its paces seem to agree that if one excludes price, the Seleccion is simply one of the best rums in HC’s stable. On Rum-X it pips the 7YO by an aggregate of 3 points (71 to 68 as of this writing) and the gap is even wider in Rum Ratings with its longer history, where, of some four hundred respondents, ¾ rate it 7/10 or better (while the Seven gets more ratings, but fewer “high” points). The Fat Rum Pirate scored it four stars in 2014, Rum Gallery 8/10, and in a more recent review, Alex over at the Rum Barrel gave it 73/100 (about 86 points on my scale).

As a matter of historical and topical interest, the Seleccion rum is not that faux Havana Club made by Bacardi for sale in the US. That brand – a bastard offspring created by the appallingly careless lapse of the “Havana Club” trademark by the Arechabala family in 1973 – is a copy of the original, and made in Puerto Rico. This one is a true Cuban product, made on the island: it is distilled from molasses and run through a column still before being set to age, and this is where the skill of the maestros roneros comes into play, because here the rum goes through a triple ageing cycle. The first round of ageing to transmute the aguardiente 1into an aged rum then the second round of ageing in used oak barrels (the exact ones used remain unclear) and then the roneros get together like elephants sniffing the wind, chose the best of those and blend them to be aged a third time in new white oak barrels for a quick burst of new flavours to round out the profile.

On the palate the rum is tawny (if that colour could describe a taste). Light white chocolate with almonds, citrus, pears, leather and coffee grounds are the first tastes one gets, a fascinating melange of sweet, sour and salt. The fruits take on more dominance at this stage: raisins, kiwi fruits, papaya, melons, figs and prunes, an interesting combo of both light and fleshy fruits. Yet at no stage do the tannins quite disappear and they balance off these other notes quite well with some molasses, licorice, peanut butter and brine, never enough to spoil the experience. It all leads to a smooth, tasty finish that combines all these elements into a spicy, tasty conclusion where the most remembered notes are leather, smoke, salt caramel ice cream and some orange zest.

Based purely on how it tastes, sips or mixes, I have to give pride of place to the Seleccion as one of the key flagbearers of the Cuban pantheon, and regret it not a bit. This is just one of those times when I have to concede that going a bit upscale — instead of sticking with the objectively safe choice dictated by the numbers — is the way to go. It’s especially the case when one tries the Seleccion in conjunction with others of similar type: the quality is self evident and just shines through and sometimes the comparison is as stark as night and day.

Most likely some will note that the cost should disqualify the rum from serious consideration, and that’s a reasonable criticism for a Key Rum, which claims to represent a more egalitarian perspective of value for money, not being a “great” or “classic” ultra-aged legend of a rum with a three figure price tag. The difficulty I have with blindly applying the letter of the restriction, however (even if it’s my own), is not only staying within the spirit of the rules generally, but in the specific definition of what exactly premium or high priced means in this instance. An average American who may get a 1.75 litre Bacardi rum of good quality for the unconscionably subsidised price of less than twenty bucks, would perhaps consider a premium to start anywhere above $25, and an ultra-premium at twice that. A European with more access and more indie bottlings on hand (all of which cost more) might consider fifty euros to be a starting point. A rich retiree, or a freshly minted (and unemployed) uni graduate would have completely different monetary criteria, as would most of us.

So that is why, here, I argue that every once in a while we have to bend that rule, go a little higher, spend a little more, in order to get something of real quality. In a world where “free” seems to be the order of the day – free internet, free social media, free samples, free reviews – it’s sometimes forgotten that real value costs something. It pays for the labour of people who provide that service or that good, and cannot always be just given away. The Havana Club Selección de Maestros is a truly premium rum that tastes truly good, but doesn’t cost a truly premium sum…just a higher one than usual. In the opinion of this reviewer, that extra price translates into a lot of extra premium, and shows, perhaps, that not all rums — whether or not they call themselves premium — can be reduced to or by something as cold as numbers. Sometimes, it’s more about the experience, and here, that experience is wonderful and a reason as good as any and better than most, to call it one of Cuba’s contributions to the Key Rums of the World.

(#932)(86/100) ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Other notes

- My thanks to Dawn Davies of the Whisky Exchange in London, who spotted me the bottle of this and the 7YO which I was able to try side by side to effect a true comparison at the 2022 Rum Show. I still owe her for both.

- The rum is a blend of rums between 8 and 15 years old.

- The labels have changed over the years but no full scale reformulation has taken place between batches. Some argue the taste is similar to the original Barrel Proof, as is the production methodology.

Tasting notes. The nose is nice. At under 50% not too much sharpness, just a good solid heat, redolent of soda, fanta, coca cola and strawberries. There’s a trace of coffee and rye bread, and also a nice fruity background of apples, green grapes, yellow mangoes and kiwi fruit. It develops well and no fault can found with the balance among these disparate elements.

Tasting notes. The nose is nice. At under 50% not too much sharpness, just a good solid heat, redolent of soda, fanta, coca cola and strawberries. There’s a trace of coffee and rye bread, and also a nice fruity background of apples, green grapes, yellow mangoes and kiwi fruit. It develops well and no fault can found with the balance among these disparate elements.