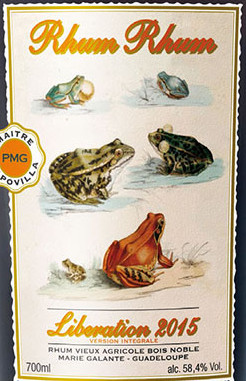

A lovely, supple rhum from the French island.

(#299 / 87/100)

***

La Confrérie du Rhum’s Martinique Extra Vieux (as labelled), a 2007 millésime rhum bottled at a forceful 52.2% had darker notes reminding me of the Damoiseau 1989, until it went off on its own path and in its own way, which makes perfect sense since it’s actually from Habitation St Etienne. And while I have not had enough of those to make any kind of statement, after trying this one I bought a few more just to see whether the quality kept pace…because La Confrérie’s rhum was quite a lovely piece of work.

The Habitation Saint-Étienne is located almost dead centre in the middle of Martinique. Although in existence since the early 1800s, its modern history properly began when it was purchased in 1882 by Amédée Aubéry, an energetic man who combined the sugar factory with a small distillery, and set up a rail line to transport cane more efficiently (even though oxen and people that pulled the railcars, not locomotives). In 1909, the property came into the possession of the Simonnet family who kept it until its decline at the end of the 1980s. The estate was then taken over in 1994 by Yves and José Hayot — owners, it will be recalled, of the Simon distillery, as well as Clement — who relaunched the Saint-Étienne brand using Simon’s creole stills, adding snazzy marketing and expanding markets.

The Brotherhood itself is an odd sort of organization, since it exists primarily on Facebook. Running the show are Benoît Bail, a sort of cheerfully roving rum junkie without an actual title but with an awesome set of tats and love of rum who currently resides in Germany, and Jerry Gitany who moonlights at Christian de Montaguère’s shop in Paris; among various other rum promotional activities, they dabble in importation of spirits, and starting in 2015 they were first approached to be part of a co-branding exercise (they are not precisely independent bottlers). What this means in practice is that they work with a distillery to chose the rum (a cask or two), put La Confrérie’s logo on the label, and designate which shops get to sell it to the final consumers, and work to promote it afterwards. So far they’ve co-branded four expressions: Les Ti’Arrangé de Céd (March 2015), Longueteau (June 2015), La Favorite (December 2015) and this one.

The story of this particular rhum started during one of Jerry’s regular visits to HSE, when Cyrille Lawson, the commercial director, remarked, “Jerry, we want to do a cuvée with La Confrérie.” “Sure,” Jerry said “But you have to do something that you’ve never done before.” And Cyrille, probably relieved not to be asked to go base-jumping in a pink suit, agreed to come up with something good. One year later, Benoît and Jerry were at HSE picking and chosing among six different samples, the final result being this first full proof 52.2% beefcake. It was distilled in a creole column still, then aged in an American oak barrel between July 2007 and February 2016, had no additives, fully AOC compliant, and turned out at a very nice 800 bottles. It turned up for sale just in time for three hundred to be snapped up at the 2016 Paris rumfest, and for me to walk into the establishment two months later, see it and want to check it out.

The story of this particular rhum started during one of Jerry’s regular visits to HSE, when Cyrille Lawson, the commercial director, remarked, “Jerry, we want to do a cuvée with La Confrérie.” “Sure,” Jerry said “But you have to do something that you’ve never done before.” And Cyrille, probably relieved not to be asked to go base-jumping in a pink suit, agreed to come up with something good. One year later, Benoît and Jerry were at HSE picking and chosing among six different samples, the final result being this first full proof 52.2% beefcake. It was distilled in a creole column still, then aged in an American oak barrel between July 2007 and February 2016, had no additives, fully AOC compliant, and turned out at a very nice 800 bottles. It turned up for sale just in time for three hundred to be snapped up at the 2016 Paris rumfest, and for me to walk into the establishment two months later, see it and want to check it out.

The aromas of the gold-amber rhum were excellent: the initial attack was all about anise, fruits, raisins, coffee and some red wine (I’m not good enough to tell you which) – this was the part that reminded me of the Damoiseaus. But then it went its own way, adding orange zest, more coffee, and some molasses (what was that doing here?), with just the slightest bit of vegetals, lemongrass and sugar cane juice. They were crisp notes that scattered like bright jewels on a field of black velvet, somehow vanishing the moment I came to grips with them, like raindrops in moonlight.

The taste, on the other hand, did not begin auspiciously – I actually thought it somewhat uncouth and uncoordinated, being sharp and spicy and seemingly harsh, but then it laughed, apologized and developed into an amazingly beautiful profile: honey, dill, candied oranges and coffee, bound tightly together by the clear hot firmness of very strong black tea. And that was just the beginning: as it relaxed and opened up (and with some water), sugar cane juice and herbals and grasses came up from behind to become more assertive (though not dominating). Again there as that odd caramel and molasses backtaste, and then came one I’m at a loss to explain except to say trust me, it was there: the scent of salt beef in a tub, hold the beef (I am not making this up, honest). It all finishing up with a lovely fade, long and warm, dry, not overly tannic, with some smoke and light dusty haylofts mixed in with chocolate, juice, zest and grass. I mean, guys, I had this thing in my glass for almost two hours while I went back and forth in that shop, and what I’m describing was real – the rhum has a phenomenal palate…less sharp than might be expected for 52.2%, and yet quite distinct and strong, a veritable smorgasbord of cooperating tastes.

Years ago when studying the games of go-masters, I remember reading that one of them lost not when he played the most promising or “proper” moves, but when following lines of play which resulted in an elegance and purity of his game which overwhelmed his desire to win. It was all about the pleasing arrangement of stones on the board, you see: the beauty. The ending was, in its own way, superfluous. Irrelevant. The pattern was everything.

I have a feeling HSE’s master blender might know this game. He started with nothing – an empty board, so to speak – and stone by stone, element by element, year by year, built a mosaic, a poem in liquid, that resulted in this fascinating rhum. He has not won, no — there are indeed weak points in the final result. But I contend that what has been made here is a thing of rare skill, of elegance, and yes, even of beauty. That alone, to me, makes it worth buying

***

Other notes

A sample straight from the bottle, one of several that Jerry Gitany let me try in Christian’s shop in Paris in early 2016. You could argue that I was positively influenced by it being a freebie, but since I picked it and he didn’t, and since a fair bit of my coin had just vanished into his till, I chose to believe otherwise.

The dates on the label make it clear this is an eight year old. Benoît confirms it is a true millésime.

As an aside, so Jerry informs me, HSE was so happy with this rhum that they asked La Confrérie to collaborate on a second batch, supposedly to be even better. It will be delivered by the end of 2016 (November or December).