Drinking this rum is knowing what harpooning Moby Dick felt like. A wild-haired full-proof bodybuilder of a rhum, so absolutely unique in taste that it it defied easy description. I sampled it and knew I wanted to write about it immediately.

So there I was in Paris at La Maison du Whiskey in April 2015, with some fellow rummies. Hundreds of bottles of rhum and rum beckoned from groaning shelves. Samples from years past – decades past! – winked in their little bottles, inviting us to get started. Straight-out rumporn, honestly. Our hands were itching to start the pours, but we were having too much fun just talking with each other to get going.

We were discussing rum classifications – colour, country, age, style – and the organizer of our ramblings (who wanted to remain nameless so I shall simply refer to him as The Sage) suggested that origin was probably best as a primary separator – pot still, single column still, multiple column still, juice versus molasses, etc – before going into further possible gradations of colour and ageing and country and style.

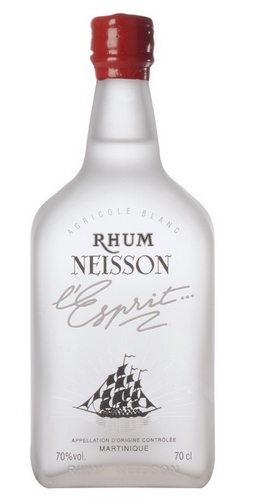

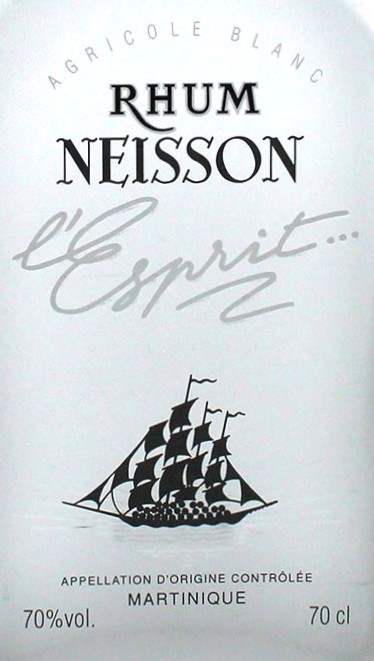

“You simply cannot mistake a pot still product, fresh off the still,” he argued. “Like Pere Labatt white, or Neisson, HSE, any of the agricole makers who produce a white rum at full proof.”

“Don’t forget Haiti,” I suggested, thinking mostly, it must be said, of Barbancourt. But also of the new stuff Velier was developing, from that half-island.

“Yes, absolutely,” said the Sage, switching directions in a heartbeat. “There are five hundred small producers in Haiti making clear rum the way they have for ages and ages. Barbancourt is good but gone mass market. If you want to see what a really original white pot still product is like, you have to try these small ones that only get sold locally, at any strength. Fully organic, old-school stuff.”

“Never tried one,” I admitted.

There was a hushed sound of indrawn breaths as the room fell silent. Serge’s impressive mustache – the one that Tom Selleck weeps himself every night to sleep wishing he had – twitched. Cyril dropped his glass, and Daniele choked into his. They all regarded me with pitying stares. The Sage himself looked utterly scandalized at my ignorance: I had evidently dropped a few notches in his esteem. After huffing and puffing his indignation for a moment, he darted behind the counter, rummaged around a bit and came back carefully holding a tasting glass brimming with a white liquid like he feared it might explode.

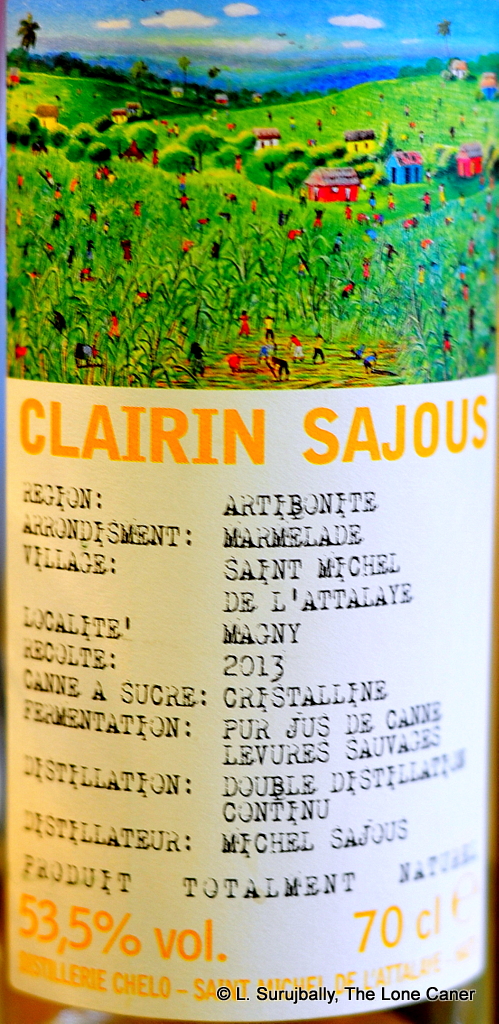

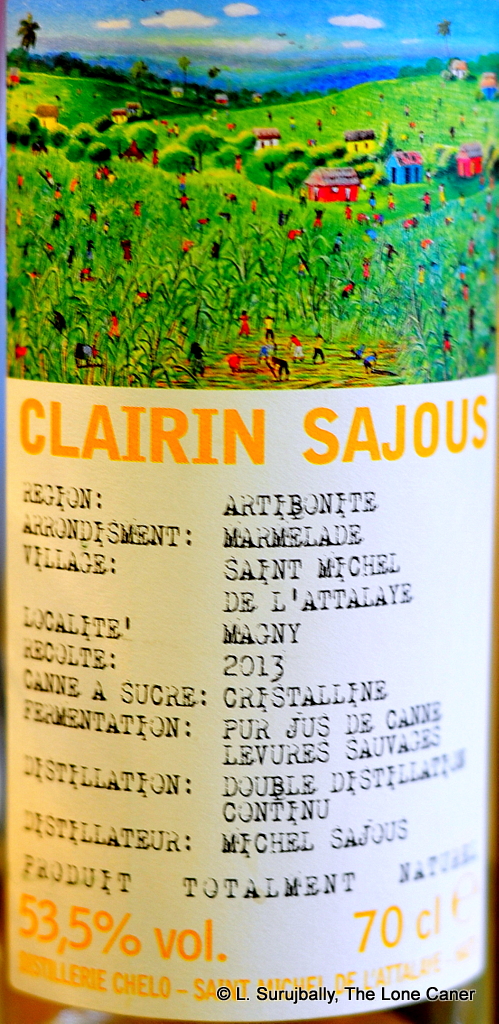

“Try this. Full proof Clairin Sajous, bottled straight from the still. 53.5%”

The term “clairin” is not a common one: references to it only exist online dating back to 2008. Clairin is, quite simply, clear white creole (often pot, sometimes primitive column) still rhum made in Haiti from cane juice, sometimes with wild yeast and a longer fermentation period, often without any ageing whatsoever. They can range from a please-don’t-hurt-me 30% or so, to (in more extreme cases) a more feral gun-toting, bring-it-on 60%. It’s the drink of the country, the way cachaca is in Brazil.

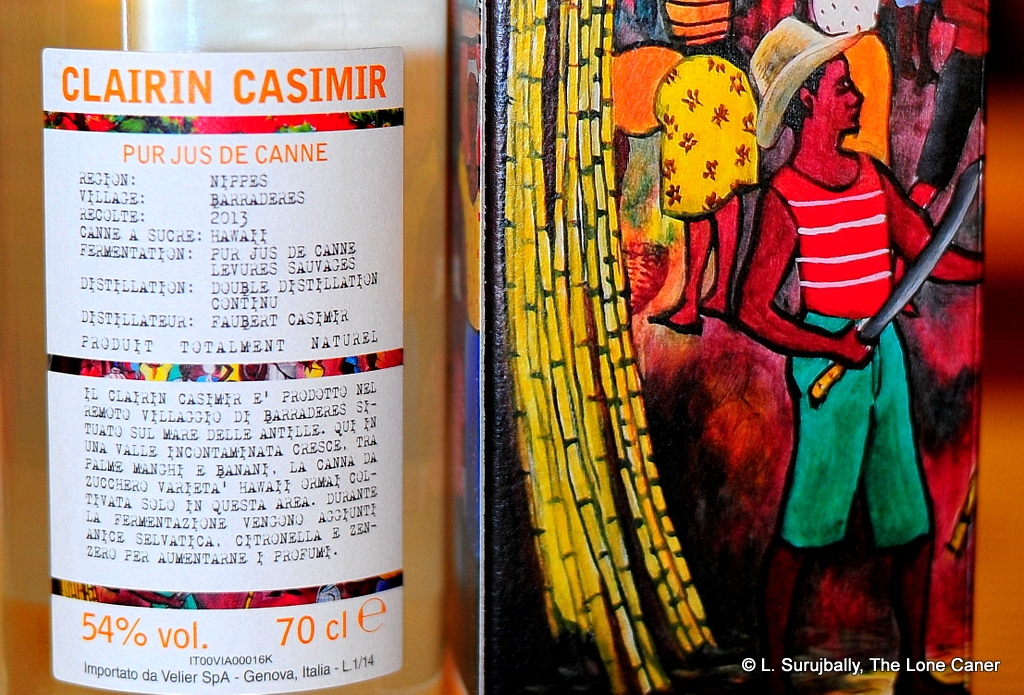

The variants of the rhum span the whole gamut of quality as well: some are rough, bathtub-brewed popskull as likely to kill you as enthuse you, bottled in whatever containers are on hand for the benefit of local consumption; others are slightly more upscale and professionally made stuff, from small one-man outfits like Sajous, Vaval and Casimir – these are occasionally sent abroad. Velier has distributed these three in its latest offerings, for example, and it was the Sajous I was trying.

The rhum looked harmless, defenceless, innocuous…meek and demure. I regarded it suspiciously as a result. I remembered traumatic incidents with cachaca, as well as unexpected clear taste bombs from Rum Nation and Nine Leaves. “Not aged at all?” I asked.

“No.”

I took a tentative pull with my nose. Even that tiny, delicate, sommelier-sniffing-the-wine sniff was too much. My eyes watered, my vision swam, my nose puckered, and my knees trembled. My God but this stuff was pungent. Not so much the strength, which was a relatively strong-but-bearable 53.5%, but its sheer intense potency. If I was older, I might have asked for a defibrillator to be on standby.

There was this incredibly large bubble of salt and wax expanding through my head. Brine and gunpowder exploded on the nose, mixed in with kerosene and fuel oil, turpentine and lacquer. It was almost like sniffing a tub of salt beef, yet behind all that, there was the herbal clarity of water in which a whole lot of sugar was dissolved (“swank” we called it in my bush-working days), crushed green mint leaves and just-mown grass on which the sprinkler is irrigating in bright sunlight.

I withdrew my nose after a few tries of this, scribbled my notes down in a shaking hand, and moved on to taste. I had learnt caution, as you can see. And if you’re trying a full-proof Clairin yourself for the first time after a lifetime of molasses-based rums, I’d recommend it.

The feel of the Sajous in the palate was hot, thick and heavy, even though the thing was not raw or excruciatingly sharp by any means. It was as intense and flavourful as the nose, if not more so – sap, thick and sweet and oily started things out. The rhum coated the tongue with the tenacity of a junkie clutching five dollar bill. I don’t often use the word “chewy” but it really works to describe how it felt. Initially the Sajous presented itself as heated and spicy, and then it smoothened out well, giving over to a buttery, and more agricole-like profile – fresh cut sugar cane, wax, furniture polish, salt beef in malt vinegar (yeah, I know how that sounds), and all shot through with green, unripe fruit, some lemon peel, and that vegetal, green flavour that drives agricole lovers into transports. More kerosene and brine permeated the back end, and the fade, long and deep, lingered for a damned long time – enough to make me put down the glass after a bit, inhale deeply and just try to wait the thing out. Before starting again.

I finally stopped my sampling, caught my breath, and looked over at Cyril from DuRhum, who was grinning at me with a glass of his own in his hand. “What did you think of it?” I asked him. He and I both liked the Nine Leaves Clear and had good things to say about Rum Nation’s 57% White Pot Still. Perhaps the closest rum to this profile I’d ever tried was the SMWS Longpond 9 81.3%). Those were similar to this, but nowhere near as uncultured, as elemental. They had been babied a little, smoothened a mite in the cuts, while this hadn’t even progressed to training wheels. It reminded me of three explosive cachacas I had tried (twice) from a small booth at the 2014 Berlin RumFest – they exhibited that same off-the-scale craziness and untamed wild freedom.

Cyril’s understatement was massively un-Gallic: “It’s different, isn’t it?” He, Daniele and The Sage were vastly amused at my reaction. I guess that was understandable – I don’t have a poker face worth a damn, and had never tried a white rhum with quite this level of profile intensity before. Just the aroma was enough to make you rethink any preconceptions of what a rum or rhum could be.

“All right then,” I said to The Sage, stealing another sip and shuddering a little less. “What can you tell me about the Sajous?”

He told me what he knew (much of which was on the label): it was made from pure sugar harvested from Java cane originating from India, grown in a small 30-hectare estate owned by Michel Sajous, in Saint Michel de l’Attalaye just north of Port-au-Prince. It was all organic and un-messed with from start to finish. Fermentation was done over seven to ten days using wild yeast, double distilled on a pot still at the Chelo distillery on the property – and then run straight into the bottles after coming off the still. No ageing, no additives, no dilution, no nothing.

“Real traditional agricole rhum before it gets tampered with, purest example of the type,” he said, and it was clear he wasn’t kidding. If there was ever an “original” rhum, the Sajous wasn’t far away from it – the only issue I had with it was perhaps a bit too much. I liked it…more or less. And the more intoxicated I got, the better it was, which may have been the point.

Cyril, Serge, Daniele, The Sage and I moved on to other things, sampled a load of old rums, went to dinner, talked about rum, drank some more, talked about rum, and had a wonderful time. They were all courteous enough to speak English to me, as my French is execrable – I got my own back by carrying on in Russian with The Sage’s beautiful better half. You’d think we would run out of things to say about rum after a while, but no – the subject was as inexhaustible as the varieties. Alas, I had to excuse myself after several hours of it, since my wife was waiting for me and probably getting grumpy.

As I walked back to my hotel, I tried to summarize my feelings about the Clairin Sajous. Without dissing the thing, I can say that this is not everyone’s rum, or a must-have unicorn you share like pictures of your first-born. In fact, Spanish and English style molasses-based rum lovers would likely never approach it again after trying it once. Even agricole enthusiasts might back off a bit. I’m scoring it reasonably high because of good production value, great heft, an enormously intriguing profile, and an original character that stands supremely alone on the prow of its self-proclaimed awesomeness, saying “Call me Sajous”. It would make a tiki drink or a complex cocktail that would blow your hair back, no problem, yet it is probably too different from the mainstream to appeal to most – in that lies both its attraction and its downfall.

Because, you see, some taming of this beast is likely to be required, before it finds real favour and acceptance in the bars of the broader rum world. I liked it for that precise reason, and will get it (and its brothers) again but must be honest enough to say I’d only buy one at a time, far apart…and always have a defibrillator handy.

(#212. 82/100)

Other notes

- Made by Sajous at Chelo, but distributed and promoted by Velier.

- For the guys I met and who took the time to talk rum, a big Merci. It really was a wonderful get-together.

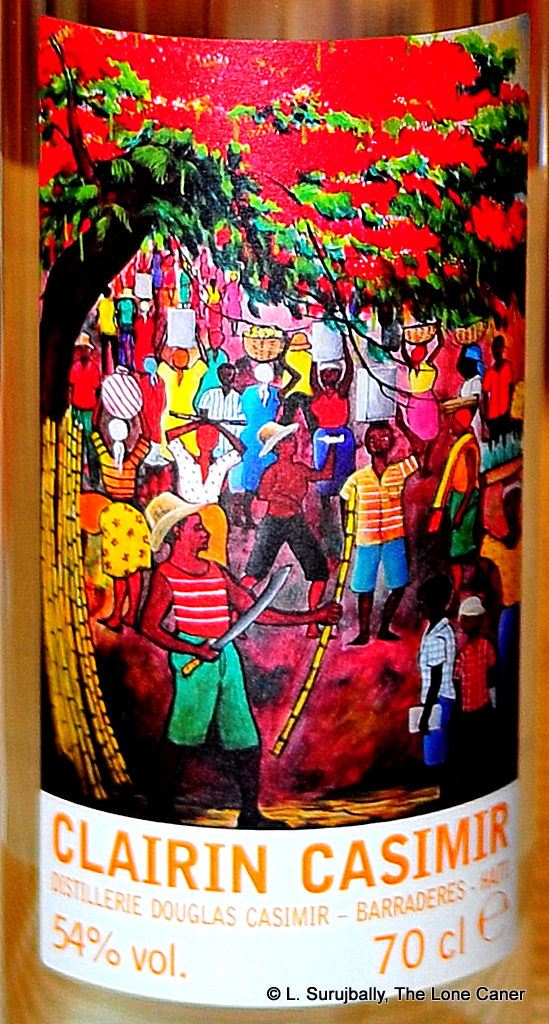

- The artwork on both this and the Casimir was done by Simeon Michel, a well known Haitian artist. There’s a better story behind the Vaval design, if you’re interested, at the bottom of the review.

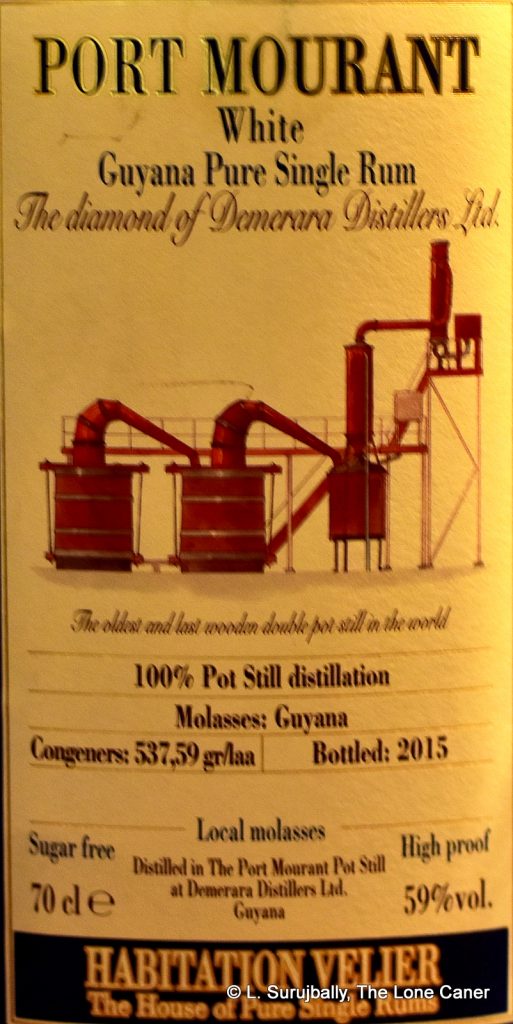

Unaged rums take some getting used to because they are raw from the barrel and therefore the rounding out and mellowing of the profile which ageing imparts, is not a factor. That means all the jagged edges, dirt, warts and everything, remain. Here that was evident after a single sip: it was sharp and fierce, with the licorice notes subsumed into dirtier flavours of salt beef, brine, olives and garlic pork (seriously!). It took some time for other aspects to come forward – gherkins, leather, flowers and varnish – and even then it was not until another half hour had elapsed that crisper acidic notes like unripe apples and thai lime leaves (I get those to buy in the local market), were noticeable. Plus some vanilla – where on earth did that come from? It all led to a long, duty, dry finish that provided yet more: sweet, sugary, sweet-and-salt soy sauce in a clear soup. Damn but this was a heady, complex piece of work. I liked it a lot, really.

Unaged rums take some getting used to because they are raw from the barrel and therefore the rounding out and mellowing of the profile which ageing imparts, is not a factor. That means all the jagged edges, dirt, warts and everything, remain. Here that was evident after a single sip: it was sharp and fierce, with the licorice notes subsumed into dirtier flavours of salt beef, brine, olives and garlic pork (seriously!). It took some time for other aspects to come forward – gherkins, leather, flowers and varnish – and even then it was not until another half hour had elapsed that crisper acidic notes like unripe apples and thai lime leaves (I get those to buy in the local market), were noticeable. Plus some vanilla – where on earth did that come from? It all led to a long, duty, dry finish that provided yet more: sweet, sugary, sweet-and-salt soy sauce in a clear soup. Damn but this was a heady, complex piece of work. I liked it a lot, really.

See, while furious aggression

See, while furious aggression