This rum is like Hooters: delightfully tacky, enjoyable as hell, and unrefined to a fault. And once you’ve given it a shot, it’s like you have a sneaking suspicion you’ll soon be back, grumbling all the while “Poukisa rum nan toujou fini?”

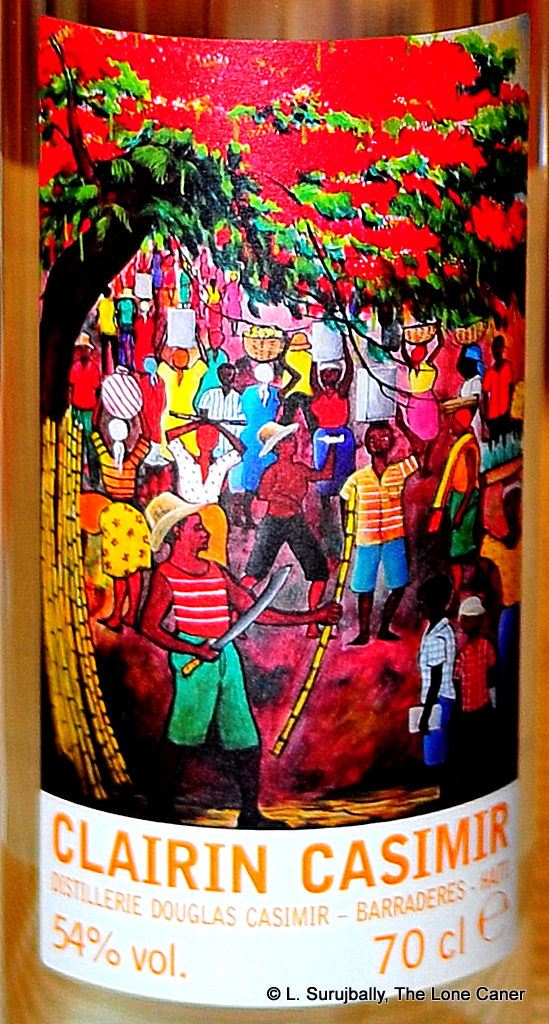

The Clairin “Casimir” white rum, the third of the Haitian Clairins, is maddening and strange if you are not in tune with it, mesmerizing if you are. I noted in a comment on the Vaval that it’s tough to love, and the same applies here, only more so. If you have not thrown the thing away in disgust after ten minutes, it’s very likely that thereafter, you will never entirely get it out of the mental arsenal of your tasting memories.

Does that make it a good rum? Not necessarily for all people, in all places…although it does make it an original, cut from wholly different cloth. And as with any such thing, we must be ready for strange detours, waves of difference and surreal experiences without clear analogues in our minds…except perhaps other Clairins. I first sampled the Sajous back in Paris in April 2015 and was enthralled on the spot; my love affair continued with the Vaval, and I felt it was only fair to get the review of the Casimir out the door just so the full set was available for those who don’t mind straying not only off the beaten path, but into another country entirely.

I make these points to prepare you for the massive pungency of the Casimir’s initial attack. As I’ve mentioned before for the other two, I recommend approaching it with care (maybe even trepidation) especially if this is your first sojourn into the world of these organic, traditionally-made, pot-still, unaged white full-proofs. Because while it initially presented to the nose very prettily, this was just a way to lure you into the same smack in the face. Powerful, pungent scents of boot polish, fusel oils, freshly lacquered wooden floors lunged smoothly out of the gate, skewering the unwary sniffer. I felt the sugar to be stronger here than on either the Vaval or the Sajous, with additional notes of soy sauce, teriyaki chicken with loads of green vegetables, Knorr packet soup, thick, heavy and my God, it didn’t ever let up. Even at a “mere” 54% it handily eclipsed the 57% Rum Nation Jamaican white pot still rum in sheer potent olfactory badassery. The Casimir quite simply makes you rethink what ageing means – nothing this young and unrefined should be this remarkable.

On the palate, I remember thinking, Man this is great. It had the smooth, hot body of an energetic and buxom porn star, and took a sharp left turn from the nose, starting out with sweet sugar water and cucumber slices in diluted vinegar…it sported a mouthfeel that alternated between silk and steel. Mint, marzipan, more floor polish, faint olive oil notes drummed on the tongue. It had less of the fusel oil that so marked the Sajous, with dill, coriander, lemon pepper, fennel, fish sauce, and some weird mineral/vegetal component that reminded me of peat for some reason. I don’t know how it managed that trick, but somehow it walked the delicate line between tongue-in-cheek titillation and overt sleaze. Really quite a lovely taste to it, the best of the trio. And the finish, no major complaints from me there either, it was long, sweet and oily, with just a note of kerosene in the background to mar what was otherwise a great drinking experience, and I gotta tell you, I really liked this one (different though it was).

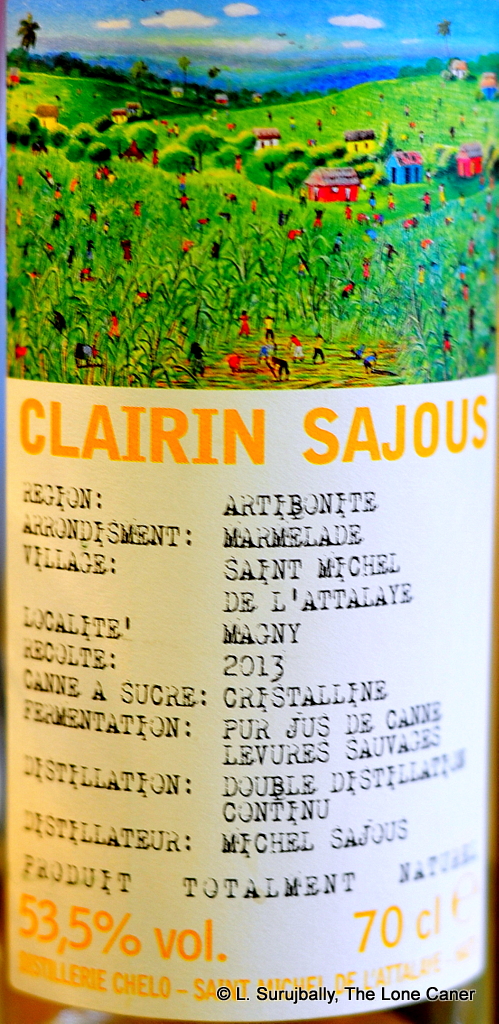

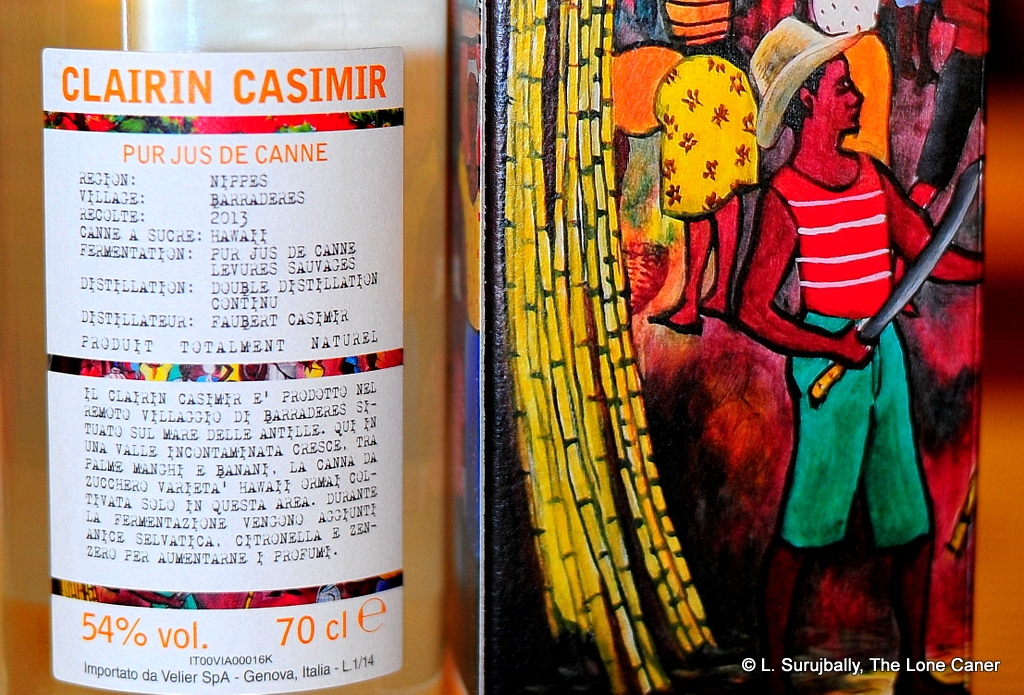

The Casimir is made by those friendly Haitian folk down by Barradères, which is a small village in the commune of Nippes Department in the southwestern leg of the half-island. It’s not far from Port-au-Prince, but still needs a tough-ass 4×4 to get to since it is (to use West Indian parlance) “way down dere behine Gad back.” Not much going on in the village, it’s subsistence farming all the way – but this small place has more distilleries than Barbados, Trinidad, Guyana and Jamaica combined – thirteen in all, though admittedly these are small-shack Mom-and-Pop operations for the most part and not industrial powerhouses in the business of stocking global shelves.

Faubert Casimir is a second generation distiller (his father began making the white lightning back in the late 1970s), and is considered by some to be the local maestro of Clairins. The rum derives from Hawaii White and Hawaii Red sugar cane grown on the 120-acre “plantation” out back, and, in a peculiarity of the region, the makers add some herbs or vegetable matter to pure cane juice in fermentation, to enhance the flavors. M. Casimir himself adds leaves of citronella, cinnamon, and in some batches, ginger, and some of that evidently carried over into the final product. Does that make it an adulterated rhum? Maybe. But for something this rich and powerful and bat-bleep-crazy, I’m willing to let it pass just to observe how joyously these guys run headfirst into a wall in making a rhum so distinct.

Of course, if you have already tried the Sajous or the Vaval (or read my notes on them both), none of this will come as news to you. And you might think, “Bah! They’re all the same, so why buy three when one can tell the tale?” You’d be right, of course…but only up to a point. They are variations on a theme, each with a subtle point of difference, a slightly different note, making each one similar, yes….and also unique. Perhaps you have to try all three to get that…or simply be deep into rums.

Yon gran mèsi, Faubert

(#248 / 86.5/100)

Other notes:

- A short video on production techniques of Casimir was released by Spirit of Haiti in 2023

- I love those bright, hectic, almost primitive labels — as an attention-getter, the bottle this rum comes in ranks somewhere between running naked through your dronish cubicle farm and throwing a brick through a shop window. The Haitian artist Simeon Michel provided the paintings for the Casimir and the Sajous (but alas, I have no clever story for this one).

Rumanicas Review 010 | 0410

Rumanicas Review 010 | 0410