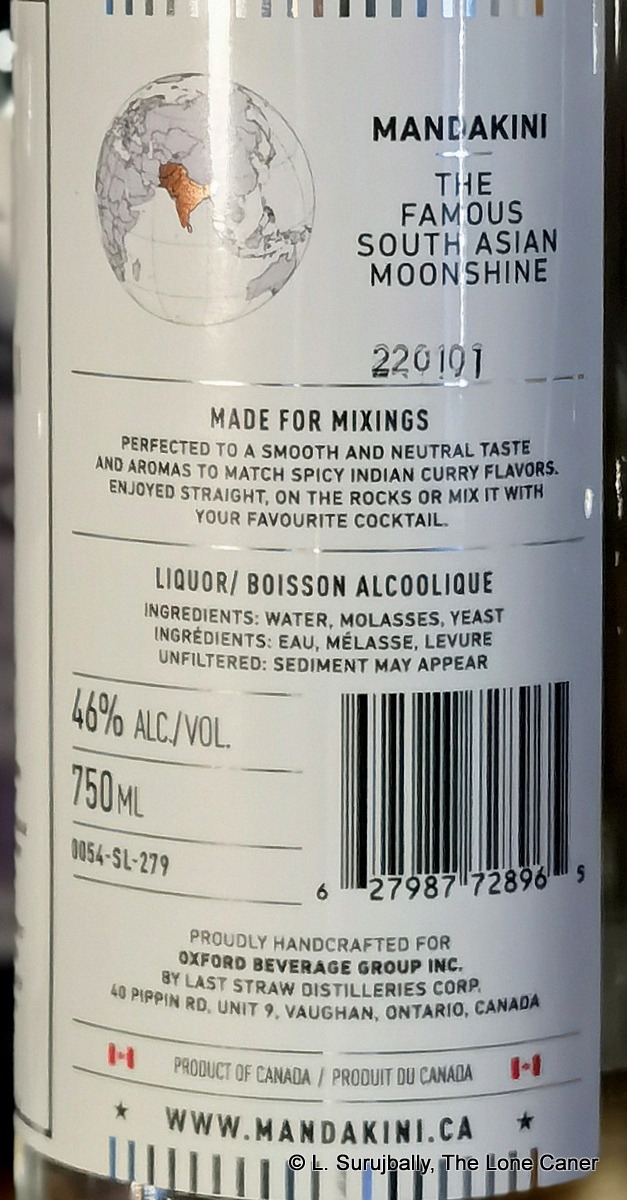

The real question is not so much how good this Malabari Vaatté, is, where it originates, or what it purports to be…but what exactly it is. Part of the issue surrounding the Mandakini is that the wording on the label could equally well be describing a real rum, a disguised alcoholic beverage claiming to be one, a spiced spirit, or some peculiar amalgam of all of the above.

The rum (I’ll use the term for now) is made in Canada, and therefore falls into the rabbit hole of the country’s arcane liquor laws, one of which, like Australia’s, states that a rum — assuming it meets the basic criteria of being made from cane derivatives like molasses, juice or vesou — can only be so labelled if it is aged for a minimum time of one year. That’s all well and good except for this catch: the same terms one would use to describe a true rum not quite meeting the criteria (for example by being a completely unaged one), are also used to describe a neutral spirit that is doctored up to be more palatable. In this case it is labelled as being an “unaged spirit from sugar cane extract” which could be either one or the other, or neither. So which is it, exactly? The producers never say.

After scanning all available sources without resolution, I finally picked up the phone and asked them directly. The bottom line is that the Mandakini derives from a wash of blackstrap molasses fermented with natural yeast for two weeks or more, and is then double-distilled through a third party’s pot-still, after which a small amount of neutral spirit is added to the mix and it’s diluted down to 46%. There’s a reason for the addition, according to Abish Cheriyam, one of the founders who very kindly took the time to tell me all about it – it’s to bring the price down so it’s affordable to the target audience, as well as smoothening out batch variation.

Trying it out (with three other Indian rums on the table as comparators) makes it obvious that this is not a rum of the kind we know, even taking into account its heritage. The nose is all sweet light candy and icing sugar, some vague sugar water, swank, lime peel, peppermint, bananas, and the kind of weak syrupy essence they dash into your flavoured coffee. Unfortunately the neutral spirit takes away from what could otherwise develop into much more interesting drink: it smells too much like a lightly sweet vodka. Those who are into Jamaican high ester beefcakes or strong unaged indigenous white rums will not find the droids they’re looking for here, and will likely note that this does not channel a genuine product made by some village still…at least not what they’ve come to expect from one.

The taste also makes this point: it is quite inoffensive, and it doesn’t feel like 46%, which to some extent is to its credit. Light, sweet, a little sharp, yet the downside is that there is too little to distinguish it. Some light florals, sugar water, coconut shavings, bananas and maybe the slightest touch of allspice. There is nothing distinctive here, and the rum feels too tamped down and softened up. I try to keep an open mind and am not exactly looking for the raw nastiness and sweat infused crap that real moonshine (like, oh, say, clairin) is often at pains to provide – but at least a hint of such brutality would have been nice. It shrugs and coughs up a touch of mint, alcohol, medicine, cotton candy, it flexes its thin body a bit, and that’s pretty much the whole ball game. The finish is short, light, has some alcohol fumes, white fruit and light candy floss to recommend it, but alas is gone faster than my paycheck into Mrs. Caner’s hands when purses are on sale.

While members of the Indian diaspora would probably get this, the rum does not channel the subcontinent to me, and that’s not a guess, because Mandakini, irrespective of its Indian origins (all three of its founders are from the southern state of Kerala), is actually made by a small craft distillery called Last Straw, in Ontario. This is a small family outfit that was founded in 2013 as a whisky distillery with two small stills; it makes all kinds of spirits on its own account — whisky, vodka, gin, rum and experimentals (including the fragrantly named “Mangy Squirrel Moonshine”) — and nowadays also does contract distilling, designing products from scratch for any client with an idea.

While members of the Indian diaspora would probably get this, the rum does not channel the subcontinent to me, and that’s not a guess, because Mandakini, irrespective of its Indian origins (all three of its founders are from the southern state of Kerala), is actually made by a small craft distillery called Last Straw, in Ontario. This is a small family outfit that was founded in 2013 as a whisky distillery with two small stills; it makes all kinds of spirits on its own account — whisky, vodka, gin, rum and experimentals (including the fragrantly named “Mangy Squirrel Moonshine”) — and nowadays also does contract distilling, designing products from scratch for any client with an idea.

Clearly Abish Cheriyam, Alias Cheriyam and Sareesh Kunjappan – engineers all, who have worked and lived in Canada for many years – had such an idea, one that they felt deeply about, though unlike the Minhas family in western Canada, they had no background in the spirits business aside from their own enthusiasm. They did however, identify some gaps in Canada’s liquor landscape: there was very little Indian liquor on the shelves aside from Amrut’s whiskies or their Two Indies and Old Port rums, and Mohan Meakin’s Old Monk; and none at all that was an Indian equivalent to vaatte, a locally distilled liquor native to Kerala (also called patta charayam or nadan vaattu charayam), which, though banned in the state since the late 1990s (a holdover from pre-independence days when the Brits forbade local liquor so as not to damage sales of their own), retains an underground popularity almost impossible to stamp out. Rural folks disdain the imported whiskies and rums and gins – they leave that frippery to city folks who can afford it, and much prefer their locally-made hooch. And like Jamaicans with their overproofs or Guyanese with their High Wine, no wedding or other major social occasion is complete without some underground village distiller producing several gallons to lubricate the festivities.

Since they could not afford to launch a distillery or wait for the endless licensing process to finish, they went to Last Straw to have them create it, and after experimenting endlessly with various blends and combinations, launched in August 2021, calling it a Malabari Vaatté (the similarity of that word to “water” is likely no accident), and aiming at the local Sri Lankan and Indian diaspora. Both the shape of the bottle and the lettering in five languages (Malayalam, Hindi, Punjabi, Tamil and Telegu) is directed at this population and the fact that the first batch sold out within days in Ontario – at the distillery, because they had not gotten a deal with the LCBO at the time – suggests it worked just fine. People were driving from all over the province to get themselves some.

In Kerala, Malabari vaatté is often made from the unrefined sugar called jaggery or from red rice like arrack, and also with any fruits or other ingredients as are on hand; it has a long and distinguished history as a perennially popular underground hooch, and that very likely comes from its easygoing nature which this one channels quite well. It shares that with other Asian spirits, like Korean shojus, Indonesian arracks, Cabo Verde grogues, or Vietnamese rượu: in other words, it is a (sometimes flavoured) drink of the masses, though Abish was at pains to emphasise that no flavourings or additives (aside from the aforementioned neutral alcohol) were included in his product.

As a casual hot weather drink and maybe a daiquiri ingredient, then, I freely admit it’s quite a pleasant experience, while also observing that true backwoods character is not to be looked for. To serious rum drinkers or bartending boozehounds who mix for a living, that’s an issue — some kind of restrained unhinged lunacy is exactly what we as rum drinkers want from such a purportedly indigenous drink. A sort of nasty, tough, batsh*t-level taste bomb that leaves it all out there on the table.

That said, I can see why it sells — especially and even more so to those with a cultural attachment for it – Old Monk tapped into that same vein many decades earlier. But that to some extent limits the Mandakini to that core audience, since people without that connection to its origins might pass it by. For all its good intentions and servicing the nostalgia and homesickness of an expatriate population far from their homelands, the Mandakini does not yet address the current market of the larger rum drinking population. It remains to be seen whether it can surmount that hurdle and become a bigger seller outside its core demographics. I hope it does.

(#1021)(74/100) ⭐⭐½

Other notes

- Video review on YouTube is here

- The name “Mandakini” is a common female name, familiar to most Indians from north or south. It was chosen not to represent anyone in particular but to instantly render it relatable and recognizable.

- The “Malabari” in the title refers to Kerala’s Malabar Coast, famed for its spices: it’s where Vasco da Gama made landfall in 1498 after rounding Africa.

- There is currently a 65% ABV version of the Mandakini called “Malabari 65”, available at the distillery in Vaughn. This is one I wouldn’t mind trying just to see how it compares. If they were to make a high ester version of that, my feeling is it would fly off the shelves.

- The range is now expanded to the original Malabari Vaatté, the 65, a Spiced Vaatté, and a Flavoured Vaatté. The latter two are apparently closer to the kind of drinks the founders initially envisioned and which are popular in Kerala, having ginger, cardamom and other spices more forward in the profile.

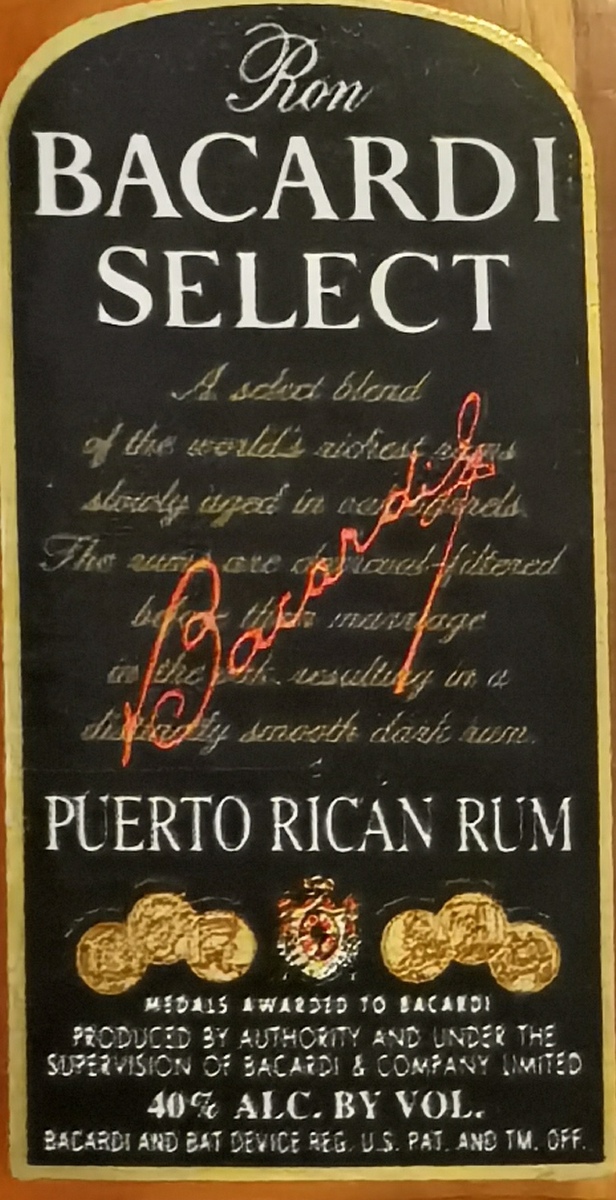

Strength – 40%

Strength – 40%