#502

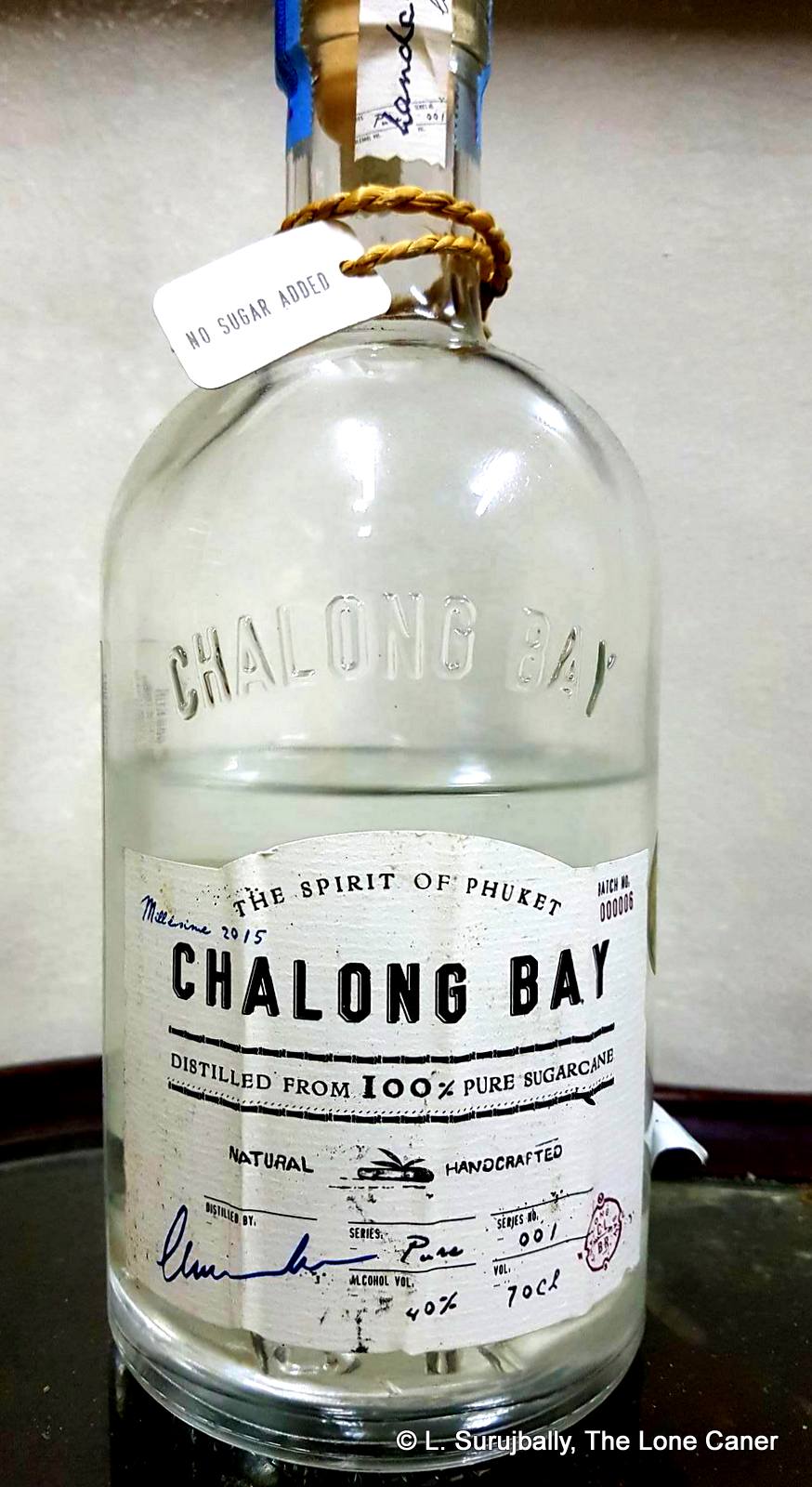

Asia may be the next region to discover for rummies. Some companies from there already have good visibility – think Nine Leaves or Ryoma from Japan, Tanduay from the Phillipines, Amrut from India, Laotian from Laos and so on – and we should not forget Thailand. So far I’ve only tried the Mekhong “rum” from there, and that was a while ago…but for the last few years I’ve been hearing about a new company called Chalong Bay, from the resort area of Phuket; and when John Go and I traded samples a while back, he sent me one of their interesting whites that for sure deserves a look-see from the curious who want to expand their horizons.

Chalong Bay is the brainchild of another pair of entrepreneurs from France (like those chaps who formed Sampan, Whisper and Toucan rums) named Marine Lucchini and Thibault Spithakis. They opened the company in 2014, brought over a copper column still from France and adhered to an all-natural production philosophy: no chemicals or fertilizers for the cane crop, no burning prior to harvesting, and a spirit made from fresh pressed cane juice with no additives. Beyond that, there’s the usual marketing stuff on their site, their Facebook page, and just about everywhere else, which always surprises me, since one would imagine the history of their own company would be a selling point, a marketing plug and a matter of pride, but no, it’s nowhere to be found.

Be that as it may, it’s quite a nifty rum (or rhum, rather), even if somewhat mild. The 40% ABV to some extend gelds it, so one the nose it does not present like one of the proud codpieces of oomph sported by more powerful blancs out there. Olives, brine, swank, generally similar to Damoiseau, J. Bally, Neisson, St Aubin blanc, or the clairins, just…less. But it is an interesting mix of traditional and oddball scents too: petrol, paint, wax, a little brie, rye bread, and just a touch of sweet sugar cane juice. Faint spices, lemongrass, light pears…before moving on to hot porridge with salt and butter(!!). Talk about a smorgasbord.

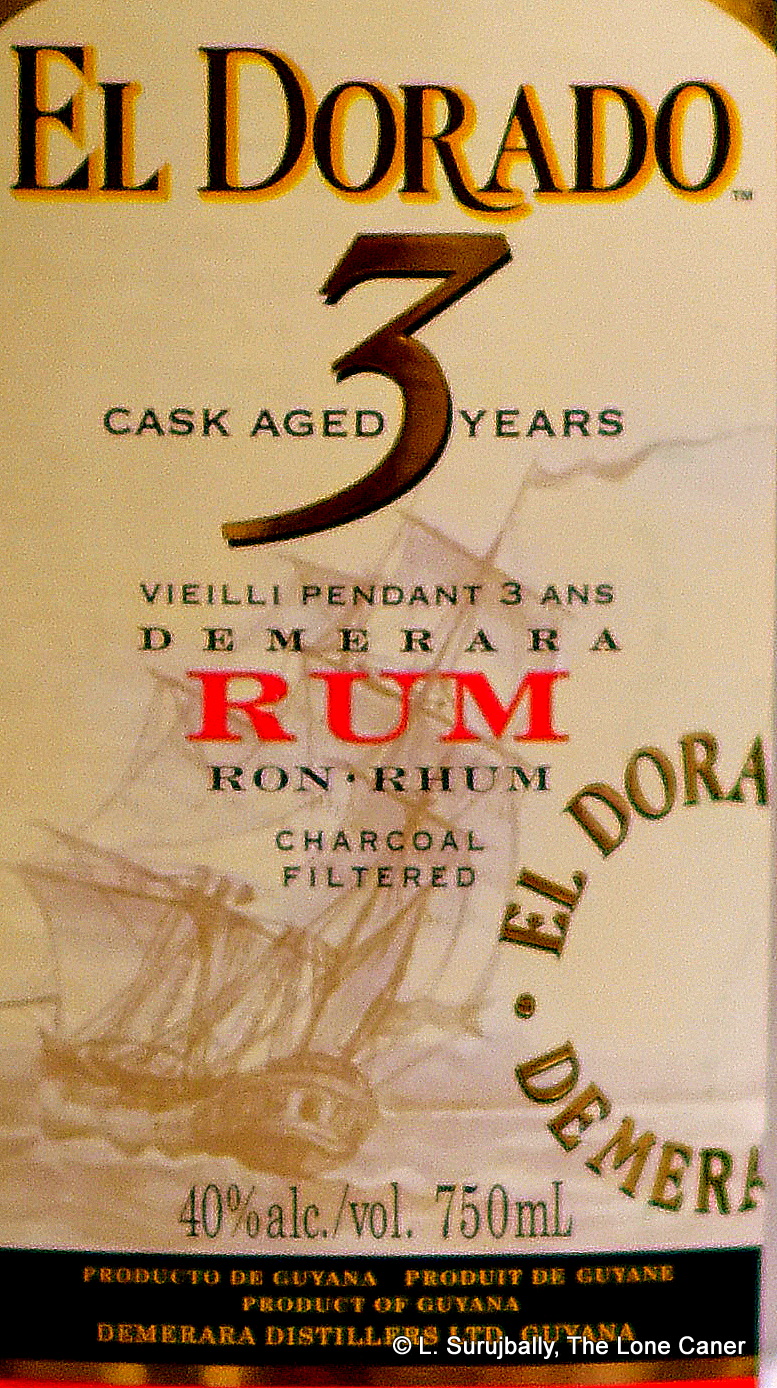

The taste on the palate takes a turn to the right and is actually quite pleasing. Thin of course (couldn’t get away from the anemic proof), a little sharp. Sweet and tart fruity ice cream. A little oily, licorice-like, akin to a low rent ouzo, in which are mixed lemon meringue pie and clean grassy tastes. Not as much complexity as one might hope for, though well assembled, and the flavours at least come together well. Citrus, pears and watermelon emerge with time, accompanied by those muffled softer tastes – cereal, milk and salted oatmeal – which fortunately do not create a mishmash of weird and at-odds elements that would have sunk the thing. Finish is short, thin, quite crisp and almost graceful. Mostly sugar water, a little citrus, avocado, bananas and brine. Frankly, I believe this is a rum, like the Toucan No 4 or the El Dorado 3 Year Old White, which could really benefit from being ratcheted up a few notches – 50% would not be out of place for this rhum to really shine.

After all is done, the clear drink finished, the unemotional tasting notes made, the cold score assigned, perhaps some less data-driven words are required to summarize the actual feelings and experience it evoked in me. I felt that there was some unrealized artistry on display with the Chalong Bay – it has all the delicacy of a sunset watercolour by Turner, while other clear full proofs springing up around the globe present brighter, burn more fiercely, are more intense…like Antonio Brugada’s seascape oils (or even some of Turner’s own). It’s in the appreciation for one or the other that a drinker will come to his own conclusions as to whether the rum is a good one, and deserving a place on the part of the shelf devoted to the blancs. I think it isn’t bad at all, and it sure has a place on mine.

(80/100)

Other notes

- Interestingly, the rum does not refer to itself as one: the label only mentions the word “Spirit”. Russ Ganz and John Go helpfully got back on to me and told me it was because of restrictions of Thail law. I’m calling it a rhum because it conforms to all the markers and specs.

- Tried contacting the founders for some background, but no feedback yet.

- The company also makes a number of flavoured variants, which I have not tried.

Yeah, 40%. I nearly put the thing back on the shelf just because of that. Just going by comments on FB, there is something of a niche market for well made 45-50% whites which DDL could be colonizing, but it seems that the standard strength rums are their preferred Old Dependables and so they probably don’t want to rock the boat by going higher (yet). I can only shrug, and move on…and it’s a good thing I didn’t ignore the rum, because it presented remarkably well, punching above its weight and dispelling many of my own initial doubts.

Yeah, 40%. I nearly put the thing back on the shelf just because of that. Just going by comments on FB, there is something of a niche market for well made 45-50% whites which DDL could be colonizing, but it seems that the standard strength rums are their preferred Old Dependables and so they probably don’t want to rock the boat by going higher (yet). I can only shrug, and move on…and it’s a good thing I didn’t ignore the rum, because it presented remarkably well, punching above its weight and dispelling many of my own initial doubts.

See, while furious aggression

See, while furious aggression