Photo copyright morealtitude.wordpress.com

In December 2014, Ian Burrell put a survey up on FB’s The Global Rum Club Page. It read: “If you had to pick 5 people who have been a major influence for the rum category, who would you pick ? It can be brand founder, distiller, blender, brand ambassador, bartender, promoter, blogger, marketer, etc. Vote for your pick or add your own major influence. I’ll throw 5 (pre 1950’s) into the mix (in no order) Don Facundo Bacardi Massó ; Ernest Raymond Beaumont Gantt AKA Don the Beachcomer; Admiral Edward Vernon aka Old Grog; Constantino Ribalaigua Vert and James Man (ED & F Man)”

I both love and hate lists. Perhaps because I’m into the numbers game as part of my day job, I love the exactitude of things nailed down and screwed shut, copper-bottomed and airtight. And so I devour top ten lists, readers favourites, drinker’s grails and all the various classifiers we humans enjoy creating so as to rank the objects of our passion. As a reviewer of rum, I dislike them intensely. Because in any subjective endeavour – be it art, literature, film, food, drink, the perfect significant other – taste and experience and quirks of personality dictate everything, and what one person might enjoy and declaim from the rooftops, another vocally despises (both with flashing eyes and elevated blood pressure). So for me to create a list of any kind is problematic, and I try not to.

Still, this one piqued my interest. Until I saw it, I sort of thought I was reasonably knowledgeable about matters of the cane (even if it’s possible I’m the only one, in the country currently called “home”). But as I went down the list, I could tell that I was as green as a shavetail louie, and my own knowledge, while extensive, couldn’t come near to figuring out who all these people were, or how they could rank in terms of influence. And of course, loving a challenge, I decided to create a small glossary for that one person who might have a question. Indulge my sense of humour as I go along…I’m kinda stoked up on hooch-infused coffee right now.

***

Don Facundo Bacardi Masso – you’re kidding right? Who doesn’t know the Catalan-born founder of Bacardi, the bête noir of those who prefer premium rums, that guy who founded the company which whips up a gajillion barrels of dronish tipple a year, and has a market cap that eclipses the GDP of small nations.

Don the Beachcomber – actually named Ernest Raymond Beaumont Gantt, hailing from Texas, he was the founding father of tiki restaurants, bars and nightclubs, often with a Polynesian flavour. A bootlegger and bar-owner (he opened Don’s Beachcomber Café in 1933 in Hollywood), he was increasingly referred to by the name of that bar. He actually changed his name several times to variations of this, until finally settling on Donn Beach. He was a lover and ardent mixer of potent rum cocktails, God love him. Supposedly created the Zombie cocktail, Navy Grog, Tahitian Rum Punch, Mai Tai and others. Trader Vic was a competitor of his (the rivalry was reputedly amicable). Died in 1989

Victor “Trader Vic” Bergeron – much like Don the Beachcomber, Victor Jules Bergeron Jr., a California native, founded a chain of Polynesian themed restaurants, which he named after his nom de guerre, “Trader Vic,” the first one way back in 1932 as a pub, which moved into alcohol in a big way as a as soon as Prohibition ended (that one was called Hinky Dink’s, renamed Trader Vic’s in 1936 and it did not have the tropical décor and flavour it later acquired). The first franchised “Trader Vic’s” restaurant/bar opened in 1940 in Seattle. It supposedly created the franchise model which many other restaurants – not the least MacDonald’s – subsequently emulated. It hit its high point in the 50s and 60s when the Tiki culture fad was at its height. Both The Trader and the Beachcomber claim to have invented the Mai Tai. There are a line of rums of the same name that are readily available in the US.

Ian Burrell – London based drinks enthusiast with his own bar not too far from Camden Town. Instrumental in organizing the annual UK Rumfest, and holds the Guinness Record for largest single tasting event (in 2014). And he started this list going. I meant to go visit his rum bar in December that year and hoist a few rarities with him, but got drunk on Woods 100 and ended up in Greenwich.

Ernest Hemmingway – Also known as “Papa” Hemmingway; journalist, war correspondent, writer, deep-sea fisherman, Nobel Prize winning author of superbly spare, masculine tales. Popularized rum and rum cocktails during his later life when he resided in Cuba, with the amusing side-effect of having every Cuban rum – and quite a few others – claiming to be his favourite and the one he liked best. Alas, he killed himself in 1960, but one hopes he had a good rum or three before deciding there was no better rum to be had and he’d better go out on a high note.

Christopher Columbus – nope, not my Italian neighbour across the way, nor a film director of fluff puff pieces. A Genoese mapmaker from the 15th century who legend has it, was looking for India when he accidentally bumped into the Caribbean islands in 1492, and promptly named the natives “Indians.” Sure glad he wasn’t looking for Turkey.

Admiral Edward Vernon (“Old Grog”, died 1757) – popularized the sadly discontinued practice of issuing rum diluted with lemon juice on board Royal Navy ships partly to ward off vitamin C deficiency (scurvy), to make shipboard drinking water more palatable, and – we can hope – to boost morale. You could argue he therefore created the first cocktail. We still, call rum “grog” because of his being affectionately named after his frock coat, called a Grogram. As a nice bit of trivia, George Washington’s estate, Mount Vernon, was named after him.

Aeneas Coffey – inventor (or perfecter) of the single column still in 1830 — he enhanced a previous 1828 design of Robert Stein’s , and this led directly to the industrial mass-production of rum; previously, pot stills were the main source of rum production, but suffered from higher costs, wide batch variation and small batch sizes of lower alcoholic content. The Coffey still addressed all these issues and kicked off the explosion of rum production (and, one can argue, the 20th century resurgence in craft pot still products). I suspect he was more interested in whisky than in rum, but nobody’s perfect.

Constantino Ribalaigua Vert – Catalan immigrant who began working in the famous Floridita fish restaurant and cocktail bar in old Havana, back in 1914…four years later he became the owner. Constantine is on this list because he invented what is one of the most famous rum cocktails ever made, the Daiquiri, somewhere in the 1930s, and it became inextricably linked with Floridita’s, which even today is known as La Cuna del Daiquiri. The bar became known for producing highly skilled cantineros whose expertise lay in crafting cocktails made with fresh fruit juices and rum, which he may have been instrumental in promoting. Hemmingway supposedly frequented the joint.

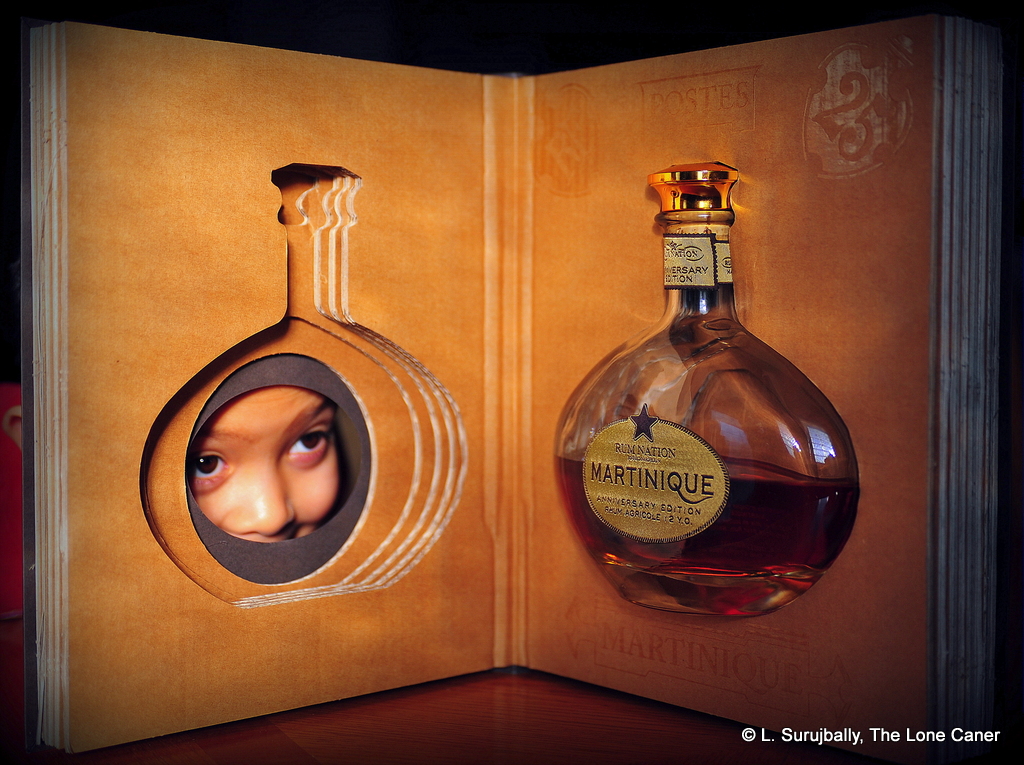

Homère Clément – founder of one of Martinique’s better known distilleries and rum houses, Clemente, which makes superlative agricoles to this day. Clemente was mayor of La Francois and purchased a prestigious sugar plantation Domaine de l’Acajou in the 1880s, just when the introduction of sugar beets was decimating the Caribbean sugar industry. He instigated the practice of using sugar cane juice to create rhum agricole, and modeled his rhums after the brandy makers and distillers of Armagnac in southwest France. I haven’t done enough research to test the theory, but Old Homere might have saved the French sugar islands from utter ruin with his rhum.

Jeff “Beachbum” Berry – Jeff is a bartender, author, contributor and cocktail personality who specializes in cocktails and Tiki culture; thus far he’s written six books on vintage Tiki drinks and cuisine, and he is referred to by the Los Angeles Times as “A hybrid of street smart gumshow, anthropologist and mixologist.” He’s created original cocktail recipes and been published in many trade, liquor, bartending and cocktail magazines. He doesn’t exclusively focus on rum, but it’s certainly a part of his overall interest, and he has raised the profile of rums in the published world like few others have.

Richard Seale – 3rd generation rum-maker; owner and manager of 4-Square distillery in Barbados, and therefore the maker of rums like Doorly’s and 4-Square brands, as well as providing barrels for many craft makers in Europe. He provided the initial distillate for St Nicholas Abbey, as they waited for their own stocks to mature. Has become a global rum icon both as a result of championing pure rums and decrying adulteration, and his collaborations with Velier.

Hunter S. Thompson – No idea why he would be on this list, except insofar as he is the author of “The Rum Diary” which is less about rum than it is about a lustful, jealous men stumbling through life in an alcoholic daze, indulging in violence and treachery at every turn (much like my Aunt Clothilde after a pub crawl). Of course, Thompson was known for imbibing colossal amounts of coke and alcohol (he was, like many young authors of the time, trying to copy the uber-mensch lifestyle of Hemmingway), so maybe this is where the connection arises. As a man with influence on rum as a whole, I’d say he’s more road kill than idol.

Rumporter – publisher of a French language magazine “Rumporter” which is dedicated like few others to the culture of rum. Too bad there isn’t an English version around, but then, I grumbled the same thing about Luca’s book. Maybe I should learn a seventh language.

The average British Navy man – also known as a Jolly Jack Tar; he needs no further intro. Lovers of Navy rums, these boys, and retired or not, keep the names of Watson’s and Woods 100 alive and well in their memories. And mine.

Don Pancho Fernandez – well known Cuban maestro ronero who worked initially for Havana Club. Developed the Zafra line of rums that are a perpetual staple in many liquor cabinets. Additionally acclaimed for the work he has done in raising the quality and profile of Panamanian rums like Varela Hermanos’s Abuelo line, Panamonte, Rum Nation and his own line of Don Pancho. Also the man behind the irritatingly named, but better-than-you-think rum Ron De Jeremy. I met him briefly in 2014. Nice guy, very courtly.

Edward Hamilton and the Ministry of Rum webpage (combined entry) – founder of the Ministry of Rum website where many rum noobs (myself among them) got their start in networking with other rum lovers. Still a very good resource to start researching producers and distillers and rums in general. Ed is also the author of “Rums of the Eastern Caribbean,” and has recently issued the Hamilton line of rums. Holds tastings and seminars all over the place and began his own line of rums in 2014. As a guy who started to pull Rummies together into an online whole, his influence cannot be underestimated – almost all rum bloggers in some way derive from what he started. These days his website is moribund, as the FB page eclipsed it.

All The Poor Slaves – and damn right too. We should never forget the backbreaking labour under inhuman conditions that slaves had to undergo to work in the fields that allowed our ancestors to sweeten their tea and create rumbullion. It is the original sin of rum.

Bartender – a good bartender is the aristocrat of the working class, knows his stuff backwards and forwards, and can whip up any cocktail you want. A great one not only knows your first name, but that of all the rums on his shelf.

Dupré Barbancourt – Founder of the eponymous distillery and rum maker on Haiti. He was a Frenchman from the cognac producing region of Charente, immigrated to Haiti and founded the company in 1862. To this day, they make some phenomenal agricoles.

Don Jose Navarro – A former Professor of Thermodynamics (ask him, not me), Don Navarro is maestro ronero for Havana Club (the Cuban one, or the “real” one). We should all be lucky enough to be able to take a right turn from our day jobs like he did in 1971.

Peter Holland – Curator, writer and owner of the website “The Floating Rum Shack.” The gentleman attends tastings around the worlds, acts as a judge of rum festivals, and is a consultant to various companies in the field. His site deals with primarily rums and cocktails. Apparently he was in Berlin in 2014, just as Don Pancho, Rob Burr and some of my other correspondents were, but we passed like ships in the night and never met each other.

Martin Cate – A San Francisco-based rum and exotic cocktail expert who collects rum like a bandit, conducts seminars and judges rum and cocktail competitions around the world; aside from that, he’s the owner of Smuggler’s Cove San Francisco, which specializes in rum cocktails, and was named by the Sunday Times of London some time back, as one of the 50 greatest bars on earth; Drinks International Magazine thought so too…three years in a row, and several other magazines think the same. I’m beginning to think I should move and crash over at Josh Miller’s place. Or just across the road from the bar.

Robert Burr –A promoter and lover of rum (and Hawaiian shirts), he is the organizer of the premier North American rum expo, the Rum Renaissance in Miami. He and his wife and son publish “Rob’s Rum Guide”, as well as hosting the Rum Renaissance Caribbean Cruise. He created the collective of judges from around the world called the RumXPs and he travels around the world judging and consulting. I met him briefly in Berlin in 2014, but he didn’t recognize my hat, which is something I really have to work on.

Father Pierre Lebat – This should probably be spelled Pere Labat; I’ll assume we’re talking about the man, because there is a rhum by that name still made on Marie Galante (Guadeloupe), where a French missionary polymath called Jean-Baptiste Labat was stationed. He was a clergyman, mathematician, botanist, writer, explorer, soldier, engineer, landowner – and slaveholder (lest we get carried away with admiration). A Dominican friar, he became a missionary and arrived in Guadeloupe in 1696 at the age of 33. While he was the procurator-general of the Dominican convents in the Antilles, he was also an engineer working for the French government; in this capacity and as proprietor of his own estate on Martinique, Labat modernized and developed the sugar industry, building on the pot still of Jean-Baptiste Du Tetre (see below). His methods for manufacture of sugar remained in use for a long time. The white agricole produced on Marie-Galante is named after him.

Luca Gargano – an exploding comet in the skies of rum, Luca made his bones by sourcing what is arguably the best collection of Guyanese still-specific rums in existence, the largest surviving Trinidad Caroni hoard any one company possesses, and in between that, issuing rums at anything between 50-65% ABV. I speak only for myself when I say that he is upping everyone else’s game, and showing that there is a market for full proof rums, just as there is for that obscure Scottish drink. And he’s a great guy.

Pirates – These guys sang shanties, shivered their timbers, pillaged, raped and plundered (and were knighted in at least one case), and drank rum. Lots of it. They may be long gone, them and all their cutlasses and pistols and sailing ships (maybe they migrated to Somalia and the South China Sea), but their shades hang around and inform the culture of rum like nothing else.

Joy Spence – The Nefertiti of the Noble spirit, Joy is the creative force behind J. Wray & Nephew, who make Appleton Estate rums in Jamaica. Since we’ve all swigged Appleton rums for decades, I’m not sure there’s much I can add here, except to note she was the first female master blender ever, and that’s quite an accomplishment in a rather male-dominated industry. With degrees in Chemistry, she took a job as a developmental chemist with Estate Industries (they produced Tia Maria) but got bored and moved on to J. Wray and Newphew, which was right next door..and there she stayed ever since. Owen Tulloch, the master blender for JW&N at the time, took her under his wing and when he retired in 1997, she became the master blender herself. So her hand is behind many of the Appletons we know and admire today. You could argue that the Appleton 50 is her and Mr. Tulloch’s love child.

Captain Morgan – The rum or the pirate? The rum is a world famous spiced baby which in some cases is not too shabby at all, and to some extent sets the bar for decent (read “non-lethal spiced overkill”) flavoured rums. The pirate did himself well. Henry Morgan, who lived and freebooted across the Caribbean in the 17th century was a privateer, not a pirate (meaning he sailed and pillaged under letters of marque issued by the English crown). He acted as an agent to harass Spanish territories and shipping, taking a cut of all plunder and ransoms. Knighted in 1674 and made Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica in 1675. He was replaced in 1681 and then gained a rep for being extremely fat and extremely drunk and extremely rowdy, like many friends of mine (and they’re all fun to hang with). Died 1688. His connection with rum is tenuous at best – about all you can say is he was a licensed pirate and a drunk. Come to think of it, so is my lawyer.

Alexandre Gabriel – the force behind Cognac-Ferrand’s magnificent Plantation double-aged line of rums. Not all of them are top end, but many are, and they have been instrumental, along with other European craft bottlers, in raising the bar for rums in general. Mr. Gabriel defends his process of dosing Plantation rums with small amounts of sugar or additives to attain the desired taste profile, which has caused some flak in the current climate regarding sugar, of “disclose or dispose.” Bought WIRD in Barbados in 2017 and in doing so gained a stake in Longpond Distillery in Jamaica.

Christian Vergier – Cellar master of New Grove rums, which is based in Mauritius. And there was me thinking the gentleman dabbled only in wines. Not much I can say about man or rum, since I’ve never met either of them. I’m sure that will change.

Oliver Rums – Created by Juanillo Oliver a Catalan-Mallorcan immigrant to Cuba in the mid nineteenth century. After the revolution in 1959 the family departed, but later re-established a sugar plantation and rum making concern in the Dominican Republic in the 1990s. They make Opthimus, Cubaney and Quohrum rums with what is supposedly the original rum recipe of the founder.

Tito Cordero – who doesn’t love the Venezuelan rum range of Diplomatico? The Reserva Exclusiva in particular receives rave reviews across the board (although I can’t speak to the ultra premium Ambassador…yet). And it’s all due to this maestro ronero, who, like Joy Spence, has a background in Chemistry (chemical engineering to be exact). And, oh yeah, he received the 2011 Golden Rum Barrel award for Best Rum Master in the world. Not too shabby at all.

Andres Brugal – the founder of Brugal and Co from the Dominican Republic. Also a Catalan (what’s with all these roneros coming from Catalonia?), he migrated from Spain to Cuba and then to the Dominican Republic in the mid 1800s…but not before soaking up equal quantities of rum and expertise. He introduced the first dark rum from his company in 1888, and over a century later, his descendants repaid the favour by naming one of their top end rums the 1888 (I liked it a lot, as a totally irrelevant aside).

James Man – Ever since I bought my Black Tot bottle, I see references to Navy rums wherever I go. And so it is here: James Man was a sugar broker and barrel maker who in 1784 secured the exclusive contract to supply rum to the British Navy. And now, more than two centuries later, his descendants, running a company called ED&F Man still trade in sugar and molasses (they are a general merchant of agricultural commodities). By the way, Man held the rum contract for 186 years – although not exclusively so for that whole time – which ended on…yup, Black Tot Day.

Silvano Samaroli – Silvano, an Italian craft bottler who started with whisky in 1968, makes this list because he may have been the first bottler to source rum, age it and issue it under his on label as a craft product in its own right. To this day I have tasted few Samaroli rums (many of my correspondents wonder what my malfunction is), but what little I’ve tried says the man’s work is superb. He died in 2017, and Fabio Rossi and Luca Gargano are his intellectual heirs.

John Gibbons – a RumXP member, rum judge, bar-trawler, independent spirit ambassador, cocktail enthusiast and rum lover. Moved to UK in 2010. Started the website Cocktail Cloister (no updates since 2011) and the Glasgow Rum Club. Does not appear to have been very active since 2013, but maybe the XP page has simply not been updated. I’ve met him a few times in Berlin, a really cool dude.

Leonardo Isla De Rum – another XP member, Leonardo Pinto has been a rum enthusiast since 2008, and curates his rum-themed website Isladerum. Nothing unusual with all this; but Leonardo has gone a step further, developing the Italian Rum Festival (ShowRum) as well as acting as a consultant for brands that wish to enter the Italian market. Honestly, I feel like a rank amateur next to people with such commitment and drive.

Muhammad ibn Zakariyā Rāzī – this guys gets my vote for sure. A Persian polymath, doctor, chemist (or alchemist, if you prefer) and philosopher, who lived around 854-925 AD. Why is he influential, and why should he be in the list? Well, leave aside his contribution to experimental medicine (he wrote a pioneering books on smallpox and measles as well as treatises on surgery that became de rigeur for western universities in the middle ages); ignore his many philosophical books, his work in chemistry and his desire for factual information not tied to traditional dogma; but just consider that he created (or at least popularized) the forerunner of all modern distillation apparatus – (drum roll) the alembic. We may now know it as a pot still and he’s the guy who is credited with spreading its usage. I’ll drink to him.

Ron Matuselam – one of the best brands of rum coming out of the Dominican Republic, and, like others, an exile from Cuba after the revolution.

Pepin Bosch – The man who could be argued to have saved Bacardi…twice. Jose M. Bosch, who died in 1994, was born in Cuba, and married into the Bacardi family. He was instrumental in rescuing Bacardi from bankruptcy during the Depression, and again in the 1960s when Castro seized all the company’s assets. Mr. Bosch ran the company from 1944 to 1976, when he retired.

E&A Scheer – A Netherlands-based ship owning company formed in the 18th century, heavily involved in the triangular trade between Europe, the West Indies and Africa – they therefore were instrumental in shipping bulk rum to Europe, at a time when (pause for loud cheers) rum was the primary tipple, and whisky wasn’t. They were also involved in shipping Batavia Arrack from the Dutch East indies at that time. By the 19th century, the company specialized in just shipping rums and then started their own blending and bulk distillation processes. To this day, they still concentrate on this aspect of the business (dealing in distillates), though they have expanded into other shipping areas as well.

Retailer –where would we be without the retailers? Too bad most corner store Mom-and-Pops don’t know half of what they sell, or speak knowledgeably about it. But then there are more specialty shops like Berry Bros & Rudd, Willow Park, Kensington Wine Market, or Rum Depot, and these guys keep the flame of expertise burning. Online retailers are going great guns too (this is where I buy 90% of what I taste these days), and if Canada were ever to get its act together regarding postage, I know a lot of guys who would be buying a helluva a lot more.

Pat O’Brien – creator of the Hurricane cocktail in the 1940s (it’s a daiquiri relative), which he made in order to rid himself of low quality rum his distributors were forcing him to accept before they would sell him more popular whiskies. At the time O’Brien was running a tavern in New Orleans (it was known as “Mr. O’Brien’s Club Tipperary” and required a password to get in during Prohibition). It is still served in plastic cups (New Orleans allows drinking in public…but not from glass containers or glasses). The name of the cocktail derives from the shape of the glass it was originally served in which resembled a hurricane lamp. O’Brien’s still exists.

Bertrand-Francois Mahe de La Bourdonnais – (1699–1753) French Naval officer and administrator, who worked in the service of the French East India company, primarily in Mauritius and Reunion. His inclusion on this list stems from his introduction of a free enterprise system on the islands, and the concomitant launch of commercial sugar (and therefore rum) production. This generated great wealth for Mauritius and Reunion, and sugar and rum have remained pillars of their economies ever since.

Jean-Baptiste Du Tertre – (1610-1687) A French blackfriar and botanist, he spent eighteen years in the Antilles and wrote many books about indigenous people, flora and fauna. His written work created the concept of the “Noble Savage”. Why is he on this list? Because he designed a rudimentary pot still (an alembic variation) to process the byproducts of sugar mills on the French islands, and thereby indirectly spurred the development of agricole rhum production upon which Pere Labat built.

Lehman “Lemon” Hart – Like Alfred Lamb and James Man, a purveyor of Navy Rums in the 1800s and liked to boast that he was the first to get such a contract but I think his license, issued in 1804, is eclipsed by Man’s (above).

George Robinson – Another master blender/distiller makes the cut, deservedly so. George Robinson was the Big Kahuna at DDL in Guyana and was in the company for over forty years (he passed away in 2011 but DDL hasn’t gotten the message yet, because their El Dorado website still has him alive and kicking. Maybe they think he’s faking it). The man was a cricketer in his youth, always a path to glory in the West Indies; however, it was his ability to harness the lunacy of the various stills DDL possesses that made his reputation and places him here. RIP, squaddie.

Capt William McCoy – I’m hoping I have the real McCoy here because no glossary of rum could be complete without at least one or five pirates, in this case a bootlegger who paradoxically never touched alcohol. The guy was unique, that’s for sure: he called himself an honest outlaw, never paid money to organized crime, politicians or the law for protection. He thought the Prohibition was daft (as do I) and made it his mission to smuggle likker from the Caribbean. He finally got collared in international waters in 1923, spent less than a year in clink, and ended his smuggling activities. He died in 1948.

Helena Tiare Olsen – Ah, Tiare. Runs one of the most comprehensive, long running and detailed cocktail blogs out there. She does rum reviews (always with the angle of what it would do for a cocktail), and until Marco of Barrel Aged Thoughts took the crown, had one of the best online articles on the stills of Guyana. Her site is an invitation to browse, there’s so much stuff there. She attends various rumfests around the world as and when she finds the time.

Daniel Nunez Bascunan – Danish blogger, rum enthusiast, owner of RumClub bar in Copenhagen and micro-brewer. Don’t know the gentlemen personally, but that bar looks awesome.

Joe Desmond – Rum XP member and mixologist. Lives in New York, acts as a judge to various festivals, collects rums and is reputed to have one of the most extensive collections in New York.

José León Boutellier – You’d think Bacardi ran out of entrants, but no, here’s another one from the House of the Bat. Sometime after Facundo Bacardí Massó came to Cuba in 1830, he inherited (through his wife) an estate of Clara Astie; this included a house, and a tenant, the French Cuban Mr. Boutellier, who ran a small distillery there which produced cognac and sweets. After hammering out the rental agreement, the two joined forces and Facundo was granted use of the pot still, creating the Bacardi, Boutellier y Co. in 1862. By 1874 Don Facundo and his sons bought out Boutellier’s stake as he declined in health. But it is clear that without Boutellier’s pot still and the happenstance of him being in that house, Bacardi would not be the same company. Small beginnings, big endings.

Jennings Stockton Cox – American mining engineer who is said to have invented the Daiquiri, perhaps because at the time when he made it, he had been working in Cuba, close to the village of Daiquiri. Supposedly running out of gin and not trusting local rum served neat, he added lime juice and sugar. Some say that Cox just popularized an already existent drink, but whatever the case, he’s now associated with it.

Rafael Aroyo – Author of an ur-text of rum-making in the 1940s – “The Production of Heavy Rum.” It is used by many home brewers as a veritable bible on how to make home-hooch. I wish I’d had it when I was a young man working in the bush. The white lightning we made could have used some expertise, and I could have saved some IQ points.

José Abel y Otero – founder of Sloppy Joe’s in Cuba just after the First World War. Immigrated from Spain to Cuba in 1904, then moved to New Orleans in 1907, then again to Miami, and returned to Cuba in 1918, where he worked in a bar called The Greasy Spoon before founding his own bodega called Sloppy Joe’s. In 1933 another bar with the same name opened in Florida (and Hemmingway was a patron…the guy sure did get around) which specifically referenced the original from Old Havana.

Alvarez & Camp – the two families who united to form Matusalem.

José Arechabala y Aldama – Founder of the Havana Club rum and the company that made it, before being expropriated following the 1959 Cuban Revolution

Robert Stein – inventor of a columnar still subsequently refined by Aeneas Coffey (see above). Stein’s 1828 still was itself inspired by the continuous whiskey still patented by Sir Anthony Perrier in 1822

George Washington – Possibly one reason the first president of the USA is on this list is because he liked rum – so much so that he demanded a barrel or two to be on hand for his inauguration. On the other hand he did operate a distillery himself on Mount Vernon, and it was the largest in the country at that time. Alas, it mostly produced whiskey.

Owen Tulloch – Joy Spence’s mentor in Appleton, he was the master Blender until 1997. I hope he and Mr. Robinson are having a good gaff somewhere up there, smoking a good Cuban, playing dominos on a plywood table, and arguing about the relative merits of El Dorado versus Appleton.

Alfred Lamb – creator of Lamb’s Navy Rum and London Dock rum in the 1800s. Another pretender to the crown, if either Lemon Hart of James Man are to be believed.

John Barrett – Managing Director of Bristol Spirits. They may not be THE name in craft spirits, but that doesn’t stop ’em from trying to grab the brass ring. Their excellent series of classic and limited edition rums are characterized by bright, eye-catching labels, great enclosures, and a quality not to be sneezed at. Their PM 1980 remains one of my favourites.

Charles Tobias – Founder of Pusser’s in the BVI in 1979 after he bought the rights and blending information for Navy Rum from the Admiralty, with the first sales beginning in 1980. They have trademarked the “Painkiller” cocktail to be made with only their rum. Mr. Tobias has always ensured that a portion of the sale of every bottle goes to charity.

Cadenhead’s – Possibly Scotland’s oldest independent bottler, founded in 1842 and a family owned and managed concern until 1972, when they were taken over by J.A.Mitchell, proprietors of Springbank distillery. While they are more staid whisky boys than rabid rummies, their unadulterated, unfiltered rums are excellent and date back to the successor of founder W.Cadenhead (Mr. Robert Duthie) who took over in 1904, and added Demerara rums to the stable. Because of bad business decisions made in the years following the death of Mr. Duthie in 1931, Christie’s auctioned off the entire stock of whisky and rum in 1972 (the same year the fixed assets and goodwill went to Springbank)…so any Cadenhead rums from this era may well be priceless.

Tony Hart – Brit rum enthusiast, rum expert, trainer of barmen, lecturer, taster, who has worked for Tia Maria and Lemon Hart, and all over the globe. Conducts tastings, workshops and seminars and spreads the gospel

4finespirits – online German rumshop which also has a pretty interesting blog. Not sure what it’s doing in this list since it’s a recently established site (2015). Somebody must sure like them. Recently started a video blog on YouTube.

Andres Brugal – full name Andrés Brugal Montaner, a Spaniard who migrated from Catalonia in Spain to Cuba (where he learned the fundamentals of how to make rum), and thence to the Dominican Republic, where he established Brugal and produced his first dark rum in 1888. The first warehouses for ageing there were built in 1920, and the company exists, making good rums, to this day. However, it is no longer owned by the Brugals, but the Edrington Group out of Scotland, who bought a majority shareholding in 2008.

Bryan Davis – This man may change the rum world, or be conning it. Opinions are fiercely divided on what the man behind Lost Spirits Distillery has accomplished. Short form is that by using chemistry and molecular analysis to build a molecular reactor, he can supposedly churn out rum which shows the profile of a 20 year old spirit…in six days. I’ve heard his rums are pretty good, but never tried any. A good article on Wired is here.

Got Rum? – online rum magazine run by Luis and Margaret Ayala

Samuel Morewood – British etymologist who wrote an essay in 1824 on the origins of the word “rum” in An essay on the Inventions and Customs of both Ancients and Moderns in the use of Inebriating Liquors. It’s actually quite a fascinating read, even now.

Cédric Brément – French maker of flavoured rums, and owner of the company Les Rhums de Ced.

Frank Ward – Chairman of the West Indies Rum and Spirits Producers Association and Managing Director of Mount Gay in Barbados. This gentleman has his work cut out for him. First to try to save the smaller Caribbean producers from the massive subsidies the big guns get, and secondly to impose some order on the crazy patchwork of rum via trying to get agreement on standards. Part of the solution is to create the Authentic Caribbean Rum Marque. An interview with Got Rum? magazine is here.

Enrique Shueg – Brother in law of Emilio, Facundo and Jose Bacardi, the three sons of the founder. Born the same year as the company was founded (1862), he steered the company almost single-handedly into the modern area, and was the key link between the small family firm and the global behemoth it eventually became. He played a leading role in the company for fifty years, expanding the reach of Bacardi to jet set visitors, tourists and even gangsters, and making Cuba the home of rum before moving operations to Puerto Rico.

Dean Martin – drinker of rum, singer and film star and member of the 1950s era Rat Pack.

Reviewers – there are so very few reviewers out there for rum (versus the hundreds who blog about whiskies). Those that enter the field have their work cut out for them, not least because of the paucity of selections which they can review on the budget they have. They serve a useful purpose in that they raise rum awareness as much as any brand ambassador or festival/competition organizer and provide useful (if free) advertising for many small outfits who might otherwise never be heard about outside their state, province, canton or country.

And there you have it. All the reference points people have made on the list. This took me the better part of a day to hammer together under the influence of both coffee and some homemade hooch, so please forgive any errors I’ve made in the spelling. It was fun to do, and I hope you who have had the stomach to read this much and have reached this point (drunk or sober), walk away with an enriched body of knowledge on rum’s past and present Big Guns.

Oh, and one other influence on rums…

All we drinkers: it is we as drinkers, writers and exponents, who make the industry. Cheers to us all!

![[prohibitioncanada.jpg]](https://1.bp.blogspot.com/_z4gXyx6hSl8/Rsxiq3m7uBI/AAAAAAAAAAk/3Dfc_9cjumw/s1600/prohibitioncanada.jpg)

I don’t know of anyone from my generation who did not at least hear of Doom. This one game – first released in 1993 – was the single most eagerly awaited offering of any software company to that time, was a landmark event that crashed the servers of the hosting BBS one minute after the midnight “opening”, and was reputedly the second most common reason quoted for the loss of productivity in offices worldwide (solitaire being the first).

I don’t know of anyone from my generation who did not at least hear of Doom. This one game – first released in 1993 – was the single most eagerly awaited offering of any software company to that time, was a landmark event that crashed the servers of the hosting BBS one minute after the midnight “opening”, and was reputedly the second most common reason quoted for the loss of productivity in offices worldwide (solitaire being the first).