Even now, all these years after the Demeraras, Caronis, Indian Ocean series, Hampdens and Habitation series, Velier continues to be able to pull out a new rabbit from the hat every now and then, something we have not quite seen in this way before. There were the last Nine Leaves expressions from last year, the Amrut from a few years back, the new Habitation Velier Nepalese rum that popped up a few months ago – and last year, at Whisky Live, they debuted the Shakara 12YO rum from Thailand.

Even now, all these years after the Demeraras, Caronis, Indian Ocean series, Hampdens and Habitation series, Velier continues to be able to pull out a new rabbit from the hat every now and then, something we have not quite seen in this way before. There were the last Nine Leaves expressions from last year, the Amrut from a few years back, the new Habitation Velier Nepalese rum that popped up a few months ago – and last year, at Whisky Live, they debuted the Shakara 12YO rum from Thailand.

Now Thailand generally does not loom large in the pantheon of countries whose rums we lust after. I’ve reviewed Sang Som and Mekhong rums in the past, and there are smaller outfits like Issan (quite good) and Chalong Bay (also very good) who are raising the profile of the country with their artisanal rums. They are at opposite ends of the divide: the former is mass market (sometimes possibly adulterated) molasses-based standard-strength tipple for the general population, and the latter is small batch, relatively limited release made from cane juice.

The Shakara rum straddles this divide. It is a molasses-based, column-still rum, made and aged completely in Thailand in the province of Nakhom Pathom, which pinpoints the distillery of origin as Sang Som, even if this is not mentioned anywhere in the available literature (the company, founded in 1977, also makes the Phraya brand of rums, for which I have tasting notes somewhere but never got around to writing about – yet). It has been aged for twelve years in situ, but again, we are not told anything about what kind of barrels they used (I’ve read elsewhere that it’s ex-bourbon), or any more detail about the production process – we can assume it’s the same as the Phraya, perhaps, but the pickings are slim there too.

Be that as it may, this is a rum bottled at 45.7%, and while we do not know the outturn, the rum is being distributed in North America as well as Europe, and we can reasonably assume there are at a minimum several thousand bottles out there, for that kind of geographical spread. It is also quite a nice mid-range rum, I think, strong enough to make it appealing, while not so high-proof as to alarm the less adventurous.

And the profile is really quite good, it must be said, even if it breaks relatively little new ground. It has an initially smoky aroma, redolent of burnt caramel, ginger, brown sugar, coconut jelly, plus some musty paper, cardboard and woody scents behind that. Leaving it to open for a while is helpful: it becomes vaguely sweet with a nice yellow mango and citrus background, together with notes of kimchi, orange peel and some iodine. Some real and surprising character emerges here, I think, yet all the while the rum remains nicely mild and is really easy nosing.

The palate does not veer too far away from this, and builds upon those notes. It is relatively quiet for the strength, a touch thin, but presents well with initial flavours of sandalwood, figs, cereal, coffee grounds, a hint of crushed walnuts, and vanilla. The brown sugar and caramel takes on a more commanding aspect here, and I think that may be a bit excessive at times, although it recedes after a few sips and doesn’t overstay its welcome too much. In all honesty, it reminds me somewhat of a dry Diplomatico, or a less sweet Zacapa – it has the same gentle vibe as those two, and slightly more of an odd edge, and it’s just not as sweet as either, which is a relief. The finish lingers just long enough to make itself known, with final touches of lemongrass, pine, mint, nuts, vanilla, salt caramel ice cream, and again, that touch of overripe orange peel.

Tasting notes are one thing, but what’s the assessment? Well, I think it’s a relatively easy, approachable sort of rum, that will be appreciated by those who prefer a more dialled down product, a blend, not a single cask pot still overproof fighting tiger like the Hampdens or the Habitation series. This is not some exacting full proof hi-test that is for connoisseurs of the top end, but a rum with more in its trousers than just its hands, and is for all to like and appreciate when something is looked for that will work well by itself or in a mix, while not being nearly as simple as it starts out.

Velier is not known for making rums for general audiences in the way that many smaller outfits do in order to make better sales and subsidize the more exclusive upscale halo bottlings, yet here, in chosing the barrels that made this blend, they have admirably found a balance between the fierce and the gentle, the connoisseurs’ jaded palate and the casual drinkers’ less demanding tastes, while taking the whole experience at slightly right angles to any kind of “standard” profile for both. That’s quite an accomplishment, I would say, for a rum so readily available, and so easily affordable.

(#1115)(83/100) ⭐⭐⭐½

Other notes

- Video recap link

- The rum cost me Can$70 at Kensington Wine Market in Calgary in April 2025, but I first tasted it at the WhiskyLive Paris in 2024.

- In his video essay on the rum, Arminder of Rum Revival mentioned that Velier picked up a bulk consignment and built a brand around that. His review is well worth watching and the backgrounder on ThaiBev (the owning company) is very useful.

- “Shakara” is the sanskrit word for sugar (some say sugar cane).

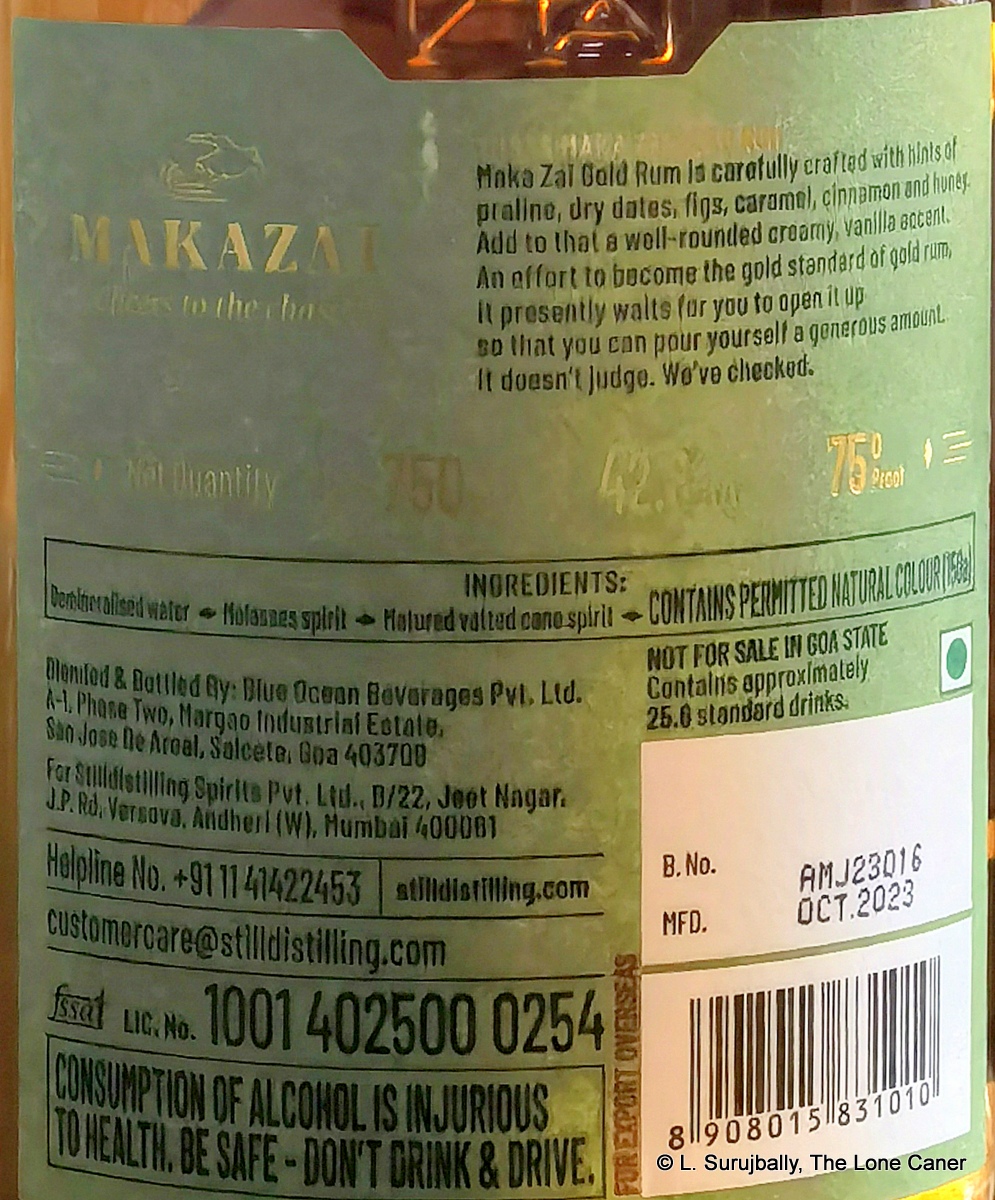

Does this multiple wood ageing result in anything worth drinking? Yes it does – the extra year seems to have had an interesting and salutary effect on the profile – though at 42.7% it remains as easy and soft as its siblings. The nose, for example, is a nice step up: cardboard, musty paper, some dunder of spoiled bananas skins, plus strawberries and soft pineapple or two and brine (which, I swear, made me think of Hawaiian pizza). Caramel and bitter dark chocolate round things off. It’s a relatively easy sniff, inoffensive yet solid.

Does this multiple wood ageing result in anything worth drinking? Yes it does – the extra year seems to have had an interesting and salutary effect on the profile – though at 42.7% it remains as easy and soft as its siblings. The nose, for example, is a nice step up: cardboard, musty paper, some dunder of spoiled bananas skins, plus strawberries and soft pineapple or two and brine (which, I swear, made me think of Hawaiian pizza). Caramel and bitter dark chocolate round things off. It’s a relatively easy sniff, inoffensive yet solid.

This process provides a tasting profile that reminds me of nothing so much than a slightly addled wooden still-rum from El Dorado: it’s sweet, feels the slightest bit sticky, and has strong notes of dark fruits, red licorice, plums, raisins and an almond chocolate bar gone soft in the heat. There’s other stuff in there as well – some caramel, vanilla, pepper again, light orange peel, but overall the whole thing is not particularly complex, and it ambles easily towards a short and gentle finish of no particular distinction that pretty much displays some dark fruit, caramel, anise and molasses, and that’s about it.

This process provides a tasting profile that reminds me of nothing so much than a slightly addled wooden still-rum from El Dorado: it’s sweet, feels the slightest bit sticky, and has strong notes of dark fruits, red licorice, plums, raisins and an almond chocolate bar gone soft in the heat. There’s other stuff in there as well – some caramel, vanilla, pepper again, light orange peel, but overall the whole thing is not particularly complex, and it ambles easily towards a short and gentle finish of no particular distinction that pretty much displays some dark fruit, caramel, anise and molasses, and that’s about it. So, until we know more, focus on the rum itself. It’s quiet and gentle and some cask strength lovers might say – not without justification – that it’s insipid. It has some good tastes, simple but okay, and hews to a profile with which we’re not entirely unfamiliar. It has a few off notes and a peculiar substrate of something different, which is a good thing. So in the end,

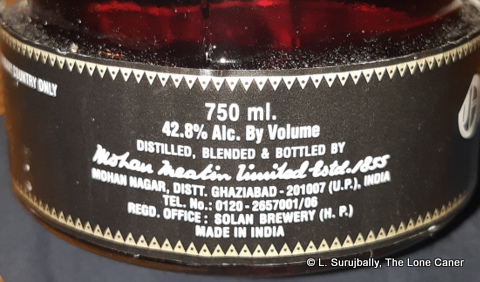

So, until we know more, focus on the rum itself. It’s quiet and gentle and some cask strength lovers might say – not without justification – that it’s insipid. It has some good tastes, simple but okay, and hews to a profile with which we’re not entirely unfamiliar. It has a few off notes and a peculiar substrate of something different, which is a good thing. So in the end,  The Old Monk series of rums, perhaps among the best known to the Western world of those hailing from India, excites a raft of passionate posts whenever it comes up for mention, ranging from enthusiastic fanboy positivity, to disdain spread equally between its lack of disclosure about provenance and make, and the rather unique taste. Neither really holds water, but it is emblematic of both the unstinting praise of adherents who “just like rum” without thinking further, and those who take no cognizance of cultures other than their own and the different tastes that attend to them.

The Old Monk series of rums, perhaps among the best known to the Western world of those hailing from India, excites a raft of passionate posts whenever it comes up for mention, ranging from enthusiastic fanboy positivity, to disdain spread equally between its lack of disclosure about provenance and make, and the rather unique taste. Neither really holds water, but it is emblematic of both the unstinting praise of adherents who “just like rum” without thinking further, and those who take no cognizance of cultures other than their own and the different tastes that attend to them.