In Part I of this short series I described the trends within and position of the rumworld as it existed before Velier began issuing its Demerara rums, and in Part II provided a listing and some brief commentary of the rums themselves, as they were released. In this conclusion, I’ll express my thinking regarding their influence, and also give an epilogue of some of the characters mentioned in Part I.

So, what made the Age? In a time when independent bottlings were already in their ascendancy, why did this one series of rums capture the common imagination to the point where many of the issues have become unicorns and personal grail quests and retail for prices that, on the face of it, are almost absurd? And what was their impact on the wider rumiverse, then and now?

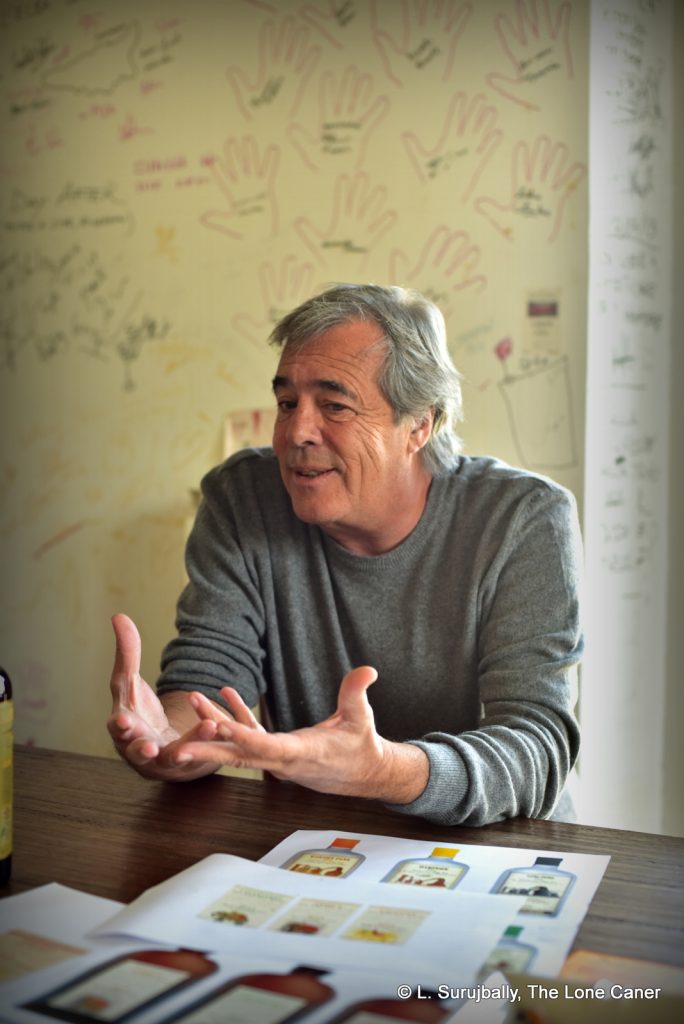

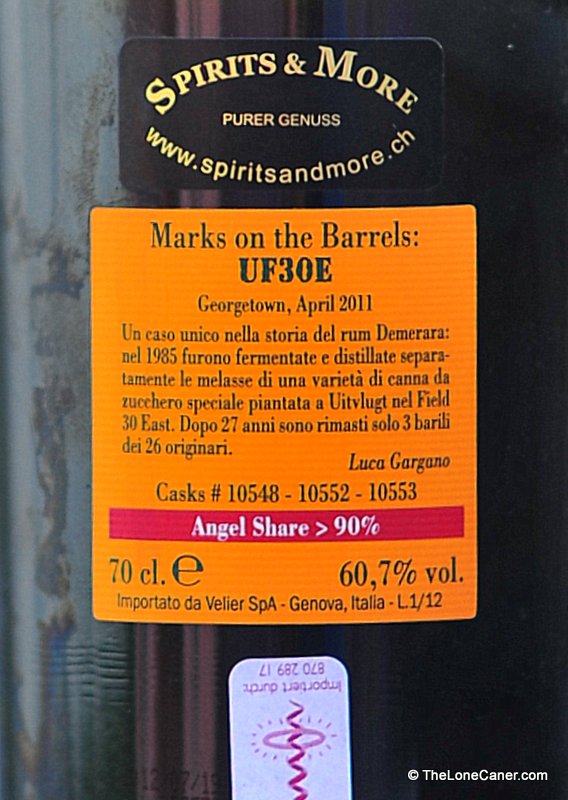

Part of their fame is certainly the proselytizing dynamism and enthusiasm of Luca Gargano himself. He is born storyteller, very focused and very knowledgeable; when you meet him, you can tell he is enraptured with the subject of rum. He travels constantly to private tastings and rumfests, and is well regarded and well known around the world. The rise of Velier is in no small part attributable to the business acumen and personal force of this one man and the dynamic team of Young Turks he employs in his offices in Genoa.

But Luca aside, I think that the Age was what it was because it really was a first, on many differing levels. It broke new ground, created (or legitimized) many new trends, and demonstrated that the rum folks would buy top quality rums even with a limited outturn. It summed up, codified and expanded principles of the rum world the way Citizen Kane did for film.

One has only to look at the way things were and the way things are to see the influence they had, and while it’s perfectly acceptable to state that Velier was only one aspect of the momentous changes in the world and the rum industry — that it was all inevitable anyway, and maybe they were just lucky bystanders who shone in reflected light of greater awareness — I contend that the Demerara series serves a useful marker in rum history that influenced much of what subsequently came along, and which we now take for granted and indeed, expect from a good rum

The Demerara rums released by Velier were several notches in quality above the equivalent rums produced almost anywhere else and entrenched the issue of tropical ageing as a viable way of releasing top quality rum, because aside from the major brands releasing their aged blends (often at 40-46%), it was almost unheard of to have tropically aged rums of such age produced at cask strength and so regularly. Almost without making a major point of it, the Age enhanced the concept of “pure”, and solidified the idea of “full proof” that otherwise might have taken much longer to get to develop.

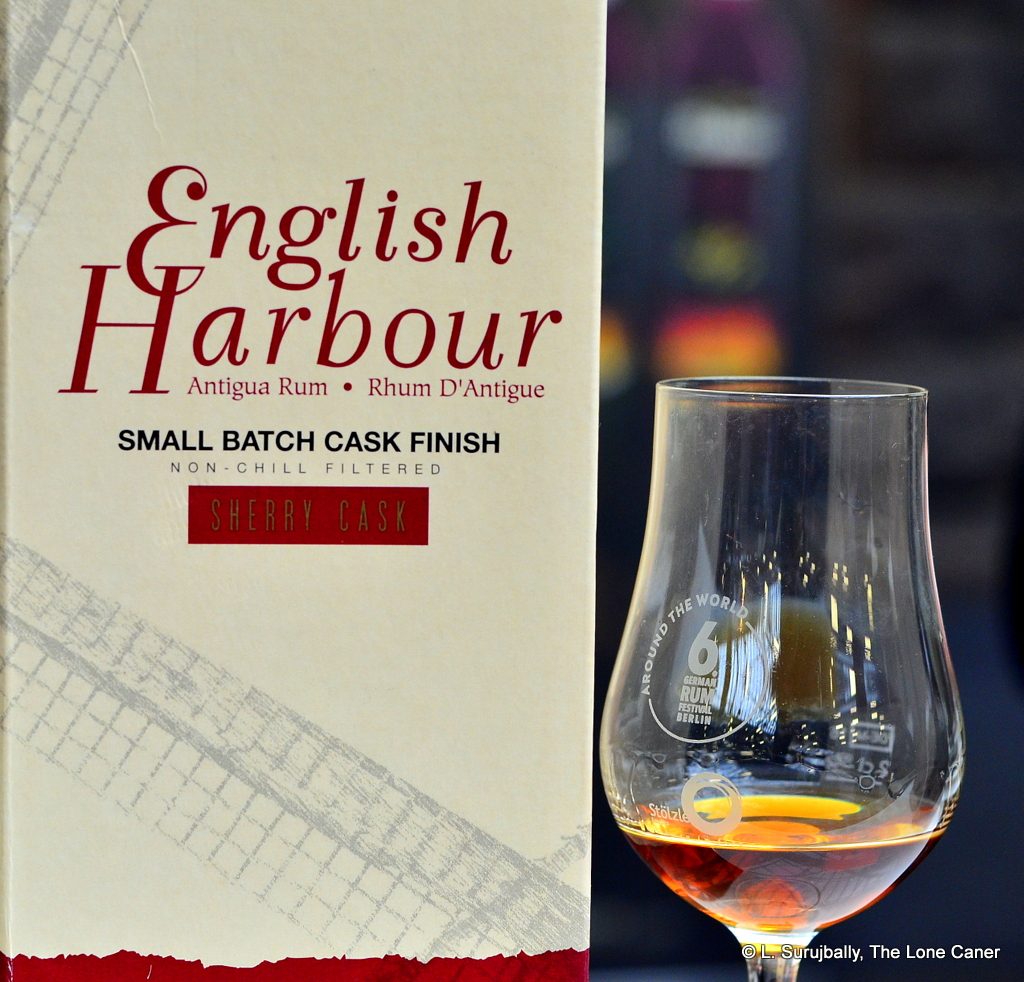

The series pointed the way to the future of Foursquare rums, Mount Gay cask strengths, the El Dorado Rares, as well as English Harbour’s and St. Lucia Distillers’ new and more powerful expressions. They provided an impetus for the re-invigorating of Jamaican distilleries, some of which were all but unknown if not actually defunct, and it could be argued that there is a line of descent from the estate-based Demerara full-proofs to the movement of these Jamaican distilleries to not just sell in bulk abroad, but to issue estate-specific marques of their own.

The Age also moved the epicenter of the top-echelon rums (not always the same as super-premiums) away from aged blends (like El Dorado’s own 21 and 25 year old rums, or Appleton’s 21 and 30 year olds) to single-barrel or limited-edition, estate-specific full proofs. It gave the French agricoles a boost via Velier’s subsequent collaboration with Capovilla (which is not to downplay the impact of the hydrometer tests mentioned below), and provided small, new rum outfits like Nine Leaves and US micro-producers the confidence that their rums made to exacting specifications, at a higher strength and without additives had a chance to succeed in an increasingly crowded marketplace.

And the Age led to a trend in increased participation of independents and private labels in the greater rum world: new or concurrently existing companies like Hamilton, EKTE, Transcontinental, Compagnie des Indes, Bristol Spirits, Mezan, Duncan Taylor, Secret Treasures, Svenska Eldevatten, Kill Devil, Excellence Rum, L’Esprit, as well as the older ones like the Scottish whisky makers, Plantation, Rum Nation, BBR, and Samaroli, are its inheritors (even if their inspiration was not a direct one and they might argue that they had already been doing so before 2005). Nowadays its not uncommon to see annual releases of many different expressions, from many different countries, instead of just a few (or one).

It would be incorrect to say that the Age of the Demeraras proceeded in isolation from the larger rum world. While these Demeraras were being made, others were also gathering a head of steam (Silver Seal and Samaroli are good examples, which is why their older bottlings are expensive rarities on par with Veliers in their own right). All the larger independent bottlers increased their issue of stronger rums from around the world. And I suggest that the work they have done when considered together has led to two of the other great divides in the rum world – cask strength versus standard, and continental (European) ageing versus tropical. To some extent Velier’s Demeraras raised awareness and provided some legitimacy for this trend if not actually initiating it.

Drejer, hydrometers, sugar and the fallout…

One other aspect of the rumworld not directly related to the Age detonated in late 2013 and early 2014, and must be considered. That was the work of the Finland’s ALKO and Sweden’s Systembolaget, closely followed by Johnny Drejer, in analyzing the contents and ABV levels of rums. They used a hydrometer to measure the actual ABV as the instruments displayed, and compared that against the labelled ABV – any difference over and beyond some kind of normal variation was an additive of some kind that changed the density. In the main, that was caramel or sugar in some form or other, and possibly glycerol and/or other adulterants.

Five short years ago, nobody on the consumer side of things ever thought to do such a test. Who could afford that kind of thing with a commercial lab? — and if the producers were doing such analyses, they weren’t publishing. For years before that, there had been rumours and dark stories of additives going around, it’s just that public domain evidence was lacking. Many producers – excepting those prohibited by law from messing around – denied (and had always denied) additives outright, or spouted charming stories about secret cellars and stashes, family recipes, old traditions and rum heritage. Most of the remainder hedged and never answered questions directly.

When the Scandinavians started publishing their results, the roof blew off — it quite literally changed the rum landscape overnight. For the first time there was proof — clear, testable, incontrovertible proof — that something was being added to some very old and well-regarded rums to change them. Almost at once Richard Seale of Foursquare used his regular attendance at international rumfests to speak to the issue (as did Luca Gargano), and he, Johnny Drejer, Wes Burgin, Rum Shop Boy, 4FineSpirits, Cyril of DuRhum, Phil Kellow, and Dave Russell proved that with some inexpensive home apparatus, you could do your own testing that would at the very least prove something else was in your favourite juice (though not what it was). All the blog owners mentioned above now maintain lists of rums and measurements of the ABV differences and the calculated dosage (that’s where the links direct you).

When the Scandinavians started publishing their results, the roof blew off — it quite literally changed the rum landscape overnight. For the first time there was proof — clear, testable, incontrovertible proof — that something was being added to some very old and well-regarded rums to change them. Almost at once Richard Seale of Foursquare used his regular attendance at international rumfests to speak to the issue (as did Luca Gargano), and he, Johnny Drejer, Wes Burgin, Rum Shop Boy, 4FineSpirits, Cyril of DuRhum, Phil Kellow, and Dave Russell proved that with some inexpensive home apparatus, you could do your own testing that would at the very least prove something else was in your favourite juice (though not what it was). All the blog owners mentioned above now maintain lists of rums and measurements of the ABV differences and the calculated dosage (that’s where the links direct you).

That direct measurement of, or reference to, a hydrometer test for ABV discrepancies has become a key determinant of honesty in labelling. Conversations in social media that speak to rums known to have been “dosed” (as the practice has come to be called) are more likely than any other to end in verbal fisticuffs and name-calling, and has created a third great divide in the world of rum drinkers.

This may be seen to be at best peripheral to the Age, but what hydrometer tests and the emergent purity movement did, was instantly (if indirectly) provide enormous legitimacy to the entire Velier Demerara line and those of many of the European indies, as well as the whole pure-rums concept Luca had been talking about for so long. With the exception of the pre-2005 releases, the credibility of these rums was solidified at once, and the increasingly positive word of mouth and written reviews moved them to almost the pinnacle of must-have rums. I’m not saying other rums and producers didn’t benefit from the movement – Jamaican, Bajan and St Lucian rums in particular were were more than happy to trumpet their own purity, as did practically every independent bottler out there – just that Velier reaped a lot of kudos almost without trying, and this helped raise awareness of their Demerara rums. It’s an aside to the main thrust of this essay, but cannot be entirely ignored either.

Epilogue

Many of the players in this short history are still with us, so here’s an update.

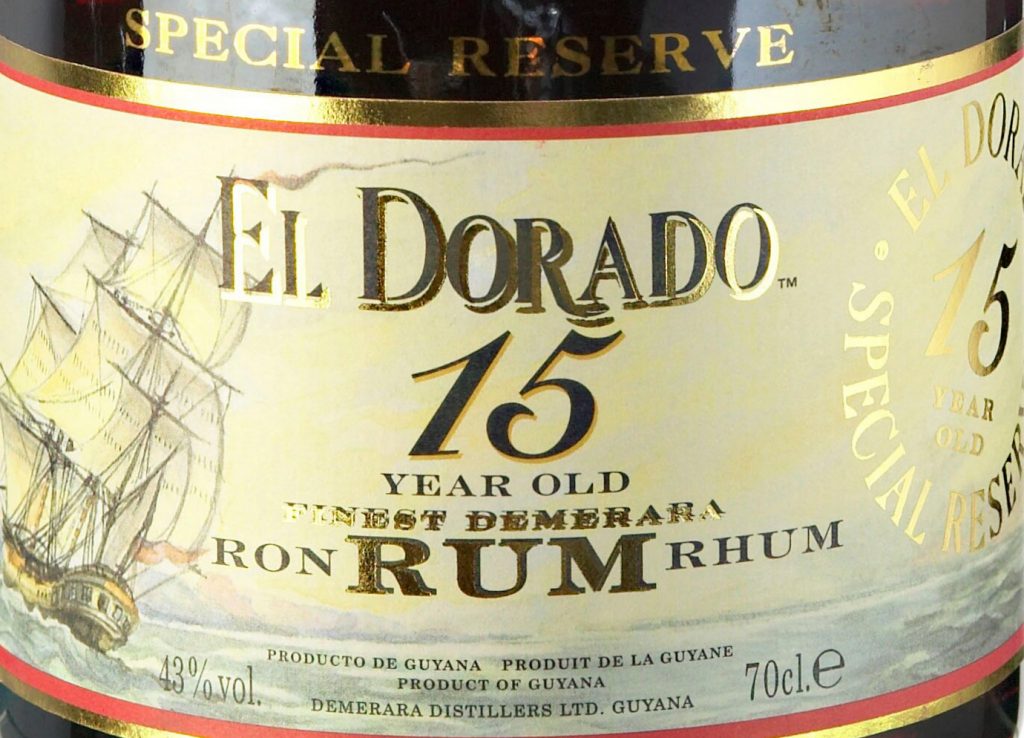

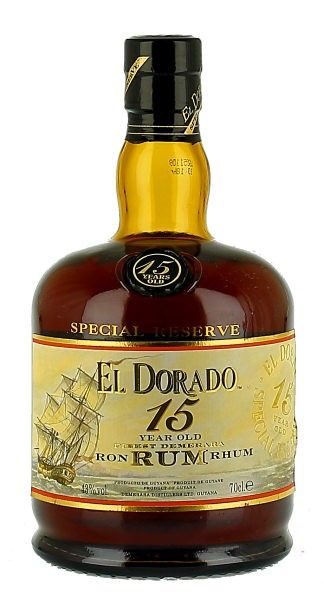

The El Dorado 15 remains a staple of the rum drinking world to this day in spite of its now well-publicized dosage. It has received much opprobrium for the lack of disclosure (DDL never commented on the matter of dosage until an interview with Shaun Caleb in 2020, and for the record the practice is being phased out) and has slipped somewhat in people’s estimation to being a second tier aged product. Yet it remains enormously popular and is a perennial best seller, a rum many new entrants to the field refer to as a touchstone, even though DDL has moved to colonize the space Velier pioneered and begun issuing cask strength limited bottlings from the stills themselves in 2016 (the 1997 anniversary editions at 40% were essays in the craft but predated the Age and were never continued).

The El Dorado 15 remains a staple of the rum drinking world to this day in spite of its now well-publicized dosage. It has received much opprobrium for the lack of disclosure (DDL never commented on the matter of dosage until an interview with Shaun Caleb in 2020, and for the record the practice is being phased out) and has slipped somewhat in people’s estimation to being a second tier aged product. Yet it remains enormously popular and is a perennial best seller, a rum many new entrants to the field refer to as a touchstone, even though DDL has moved to colonize the space Velier pioneered and begun issuing cask strength limited bottlings from the stills themselves in 2016 (the 1997 anniversary editions at 40% were essays in the craft but predated the Age and were never continued).

Photo (c) A Mountain of Crushed Ice

Ed Hamilton has withdrawn somewhat from his publishing and promotional work, and the Ministry of Rum website is a shadow of its glory days, with most of the traffic and rum-chum interaction shifting to Facebook, where his group is one of the top five in the world by user base. Mr. Hamilton is a distributor of many distilleries’ rums into North America and in 2010 began to issue the Hamilton line of rums from around the Caribbean, all pure, all at cask strength. I quite liked the little I’ve tried.

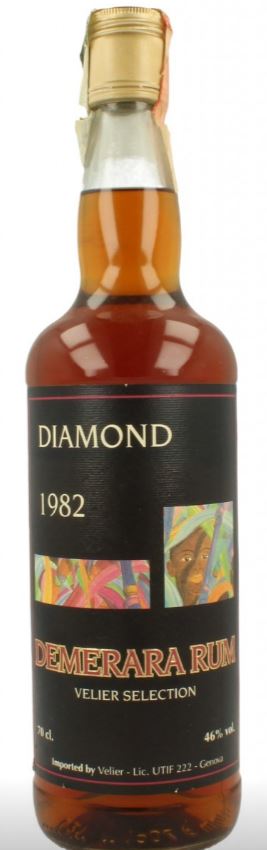

Independent bottlers continue proliferating in Europe and all follow the trail of the Age – full proof, estate (or country) specific rums. When from Guyana, it is now standard practice for the still to be referenced, with the “Diamond” moniker being perhaps the most confusing.

The internet has enabled not just one rum forum on one website, but a whole raft of international rum review websites from the USA, Australia, Japan, France, Germany, Denmark, Spain, and the UK. Oddly, the Caribbean doesn’t have any (and I’m not sure that I qualify, ha ha). There are also news aggregators and online shops in a quantity that astounds anyone who saw it develop in so short a time. Aside from private sales on Facebook, websites are now one of the most common ways to source rums as opposed to walking into a shop. The many Facebook rum clubs are the sites of enormously spirited discussions – these clubs (and to a lesser extent reddit) are the places to get the fastest response to any rum question, and the best in which to take a beating if you profess admiration for a dosed rum.

Johnny Drejer and the others mentioned above are still updating rum sugar lists. They cover most common rums. The test is now considered almost de rigueur. It has its detractors – it can be impacted by more than just sugar, temperature variations affect the readings, it can be fooled by higher actual ABV being labelled as less, and you never know quite what’s been added – but it remains one of the strongest tools in the ongoing battle to have additives or dosage disclosed properly.

Luca Gargano of Velier, April 2018, Genoa

Velier has grown into one of the great distributors, enablers and independents of the rumworld (though they remain at heart a distributor), and not rested on their laurels, but gone from strength to strength. Luca, always on the lookout for new and interesting rums, scored a massive coup when he picked up thousands of barrels from the closed Trinidadian distillery Caroni in 2004. Velier has been issuing them in small batches for years, so much so that it could be argued that as the sun of appreciation set over the Age of Demeraras, it rose on the Age of Caroni (at least in the public perception). He has championed artisanal rums from Haiti and anywhere else where traditional, organic and pure rums are made. He has forged partnerships and fruitful collaborations with producers around the world. One, with Richard Seale of Foursquare resulted in the conceptual thinking behind the Exceptional Series, as well as the collaborations of Habitation Velier, which are tensely awaited and snapped up fast by enthusiastic and knowledgeable rum folks. He has an involvement with Hampden out of Jamaica, and when the 70th Anniversary of Velier rolled around in 2017, partnered up with many producers to get special bottlings from them to mark the occasion. Velier has grown into a company with a scores of employees, and a turnover hundreds of times greater than that with which it began.

I appreciate this sounds like something of a hagiography, but that is not my intention. The purpose of this long essay and this wrap-up, is simply to place the Demerara rums issued during those years at the centre of great changes in our world. (Not the Caronis, because I contend that the appreciation for them took much longer to gestate; not so much the Rhum Rhum line done with Capovilla, since they remain something of a niche market, however popular; and certainly not the one-offs like the Basseterre 1995 and 1997 or the Courcelles 1972, which were too small and individualistic). The Age’s rums did not create all the trends noted above single-handedly. But certainly they had a great influence, and this is why we can correctly refer to an Age, even if it is just to mark the time when a series of exceptional bottlings were made.

It is my belief that what the Demerara series of rums did was to point the way to possibilities that were, back then, merely small-scale, limited or imperfectly executed ideas, waiting to be taken to the next level, like Birth of a Nation and Citizen Kane did for movies in 1915 and 1941. Velier came in, took a look around and re-imagined the map, then went ahead and showed what could be done. Certainly, like most innovators, Luca built on what came before while amending and modifying it to suit his own personal ideas; others contributed, and Velier did not work outside the great social and spirituous trends of its time. But somehow, Luca more than most gathered the strands of his imagination and used them to tie together all the concepts of rum making in which he believed. In doing so he produced rums which remain highly sought-after, and used the credibility they engendered to put his stamp firmly on the industry. We live in the world that he and his rums helped to bring about. Whatever your opinions on the influence of the Age, we had what we had before they appeared, and now we have what we have which is better. The work is worth acknowledging, and respecting. It is to our regret that the Age was over before we even properly acknowledged its existence.

In closing, I should mention that the Age of Velier’s Demeraras was only called that when it was over (and for the record, it was by the Danish blogger Henrik Kristoffersen who first used the term in a Facebook post in early 2016). And even if you don’t believe the Age was so central, or had the sort of rum-cultural impact as I think they do, I believe there’s no gainsaying that the sheer quality of rums that were issued for those nine years supports the idea that there was once an Age, that it really did exist…and the current crop of rums from this company remain at a similar level of quality as those first old and bold ones which were once considered too expensive. It’s great that even now with all their rarity, we can sometimes, just sometimes, still manage to drink from the well of those amazing Demeraras, and consider ourselves fortunate to have done so.

***

This series elicited an interesting discussion on Reddit regarding topical ageing vs continental, here.

As noted in Part 1, after a few years of developing the company and broadening its portfolio, Velier began its move to craft spirits in 1992 (which may not be a coincidence), by beginning its selection of barrels of rum for its brand. This led, in 1996, to the issuance of three Guyanese rums – all issued at 40% (see next paragraph) and using a third partly bottler (Thompson & Co.). All were continentally aged.

As noted in Part 1, after a few years of developing the company and broadening its portfolio, Velier began its move to craft spirits in 1992 (which may not be a coincidence), by beginning its selection of barrels of rum for its brand. This led, in 1996, to the issuance of three Guyanese rums – all issued at 40% (see next paragraph) and using a third partly bottler (Thompson & Co.). All were continentally aged. Luca was dissatisfied with this, and four years later tried again, with three more rums from Guyana. These were bottled by a Holland-based subsidiary of DDL themselves (called Breitenstein), because by this time Velier’s association with DDL had become much firmer and it was felt to be more cost effective – though they remained continentally aged. Of particular note was Luca’s find of the LBI marque, quite rare, though which still produced it remains an open question. The Enmore also comes in for mention because of its strength – it was the first attempt to issue at full proof…why he did not follow on from this concept here is unknown, but considering that the

Luca was dissatisfied with this, and four years later tried again, with three more rums from Guyana. These were bottled by a Holland-based subsidiary of DDL themselves (called Breitenstein), because by this time Velier’s association with DDL had become much firmer and it was felt to be more cost effective – though they remained continentally aged. Of particular note was Luca’s find of the LBI marque, quite rare, though which still produced it remains an open question. The Enmore also comes in for mention because of its strength – it was the first attempt to issue at full proof…why he did not follow on from this concept here is unknown, but considering that the

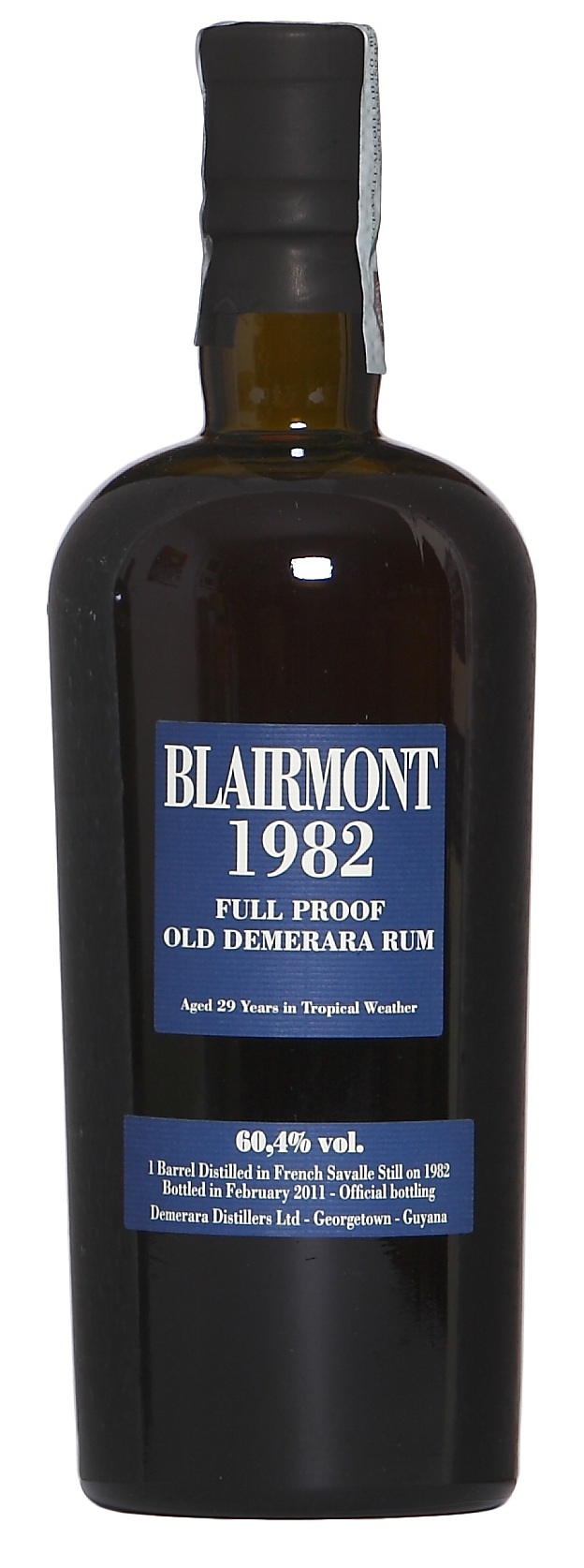

2005 and 2006 together saw the issuance of not only eight different Guyanese rums but nine and eight Caronis respectively. None of these received especially wide acclaim or attention, though my feeling is that the 1991 Blairmont was definitely one of the better rums I’ve tried from the stable and the one occasion I tried (without notes) the PM 1993, it was equally impressive, though relatively young compared to its siblings issued in those two years.

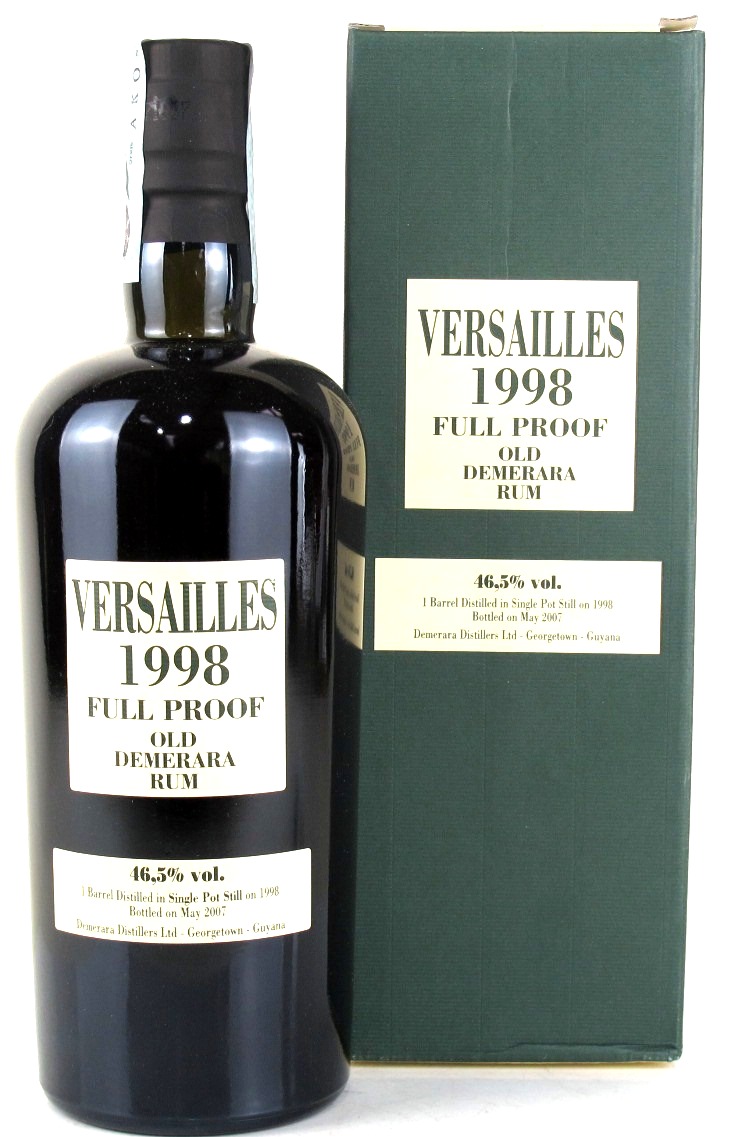

2005 and 2006 together saw the issuance of not only eight different Guyanese rums but nine and eight Caronis respectively. None of these received especially wide acclaim or attention, though my feeling is that the 1991 Blairmont was definitely one of the better rums I’ve tried from the stable and the one occasion I tried (without notes) the PM 1993, it was equally impressive, though relatively young compared to its siblings issued in those two years. 2007 was an odd year, when everything issued was under ten years old, which may just have been a function of what was put in front of Luca to inspect and select. The first Versailles rum since 1996 was issued in 2007, and somehow another LBI rum was found – it would prove to be the last.

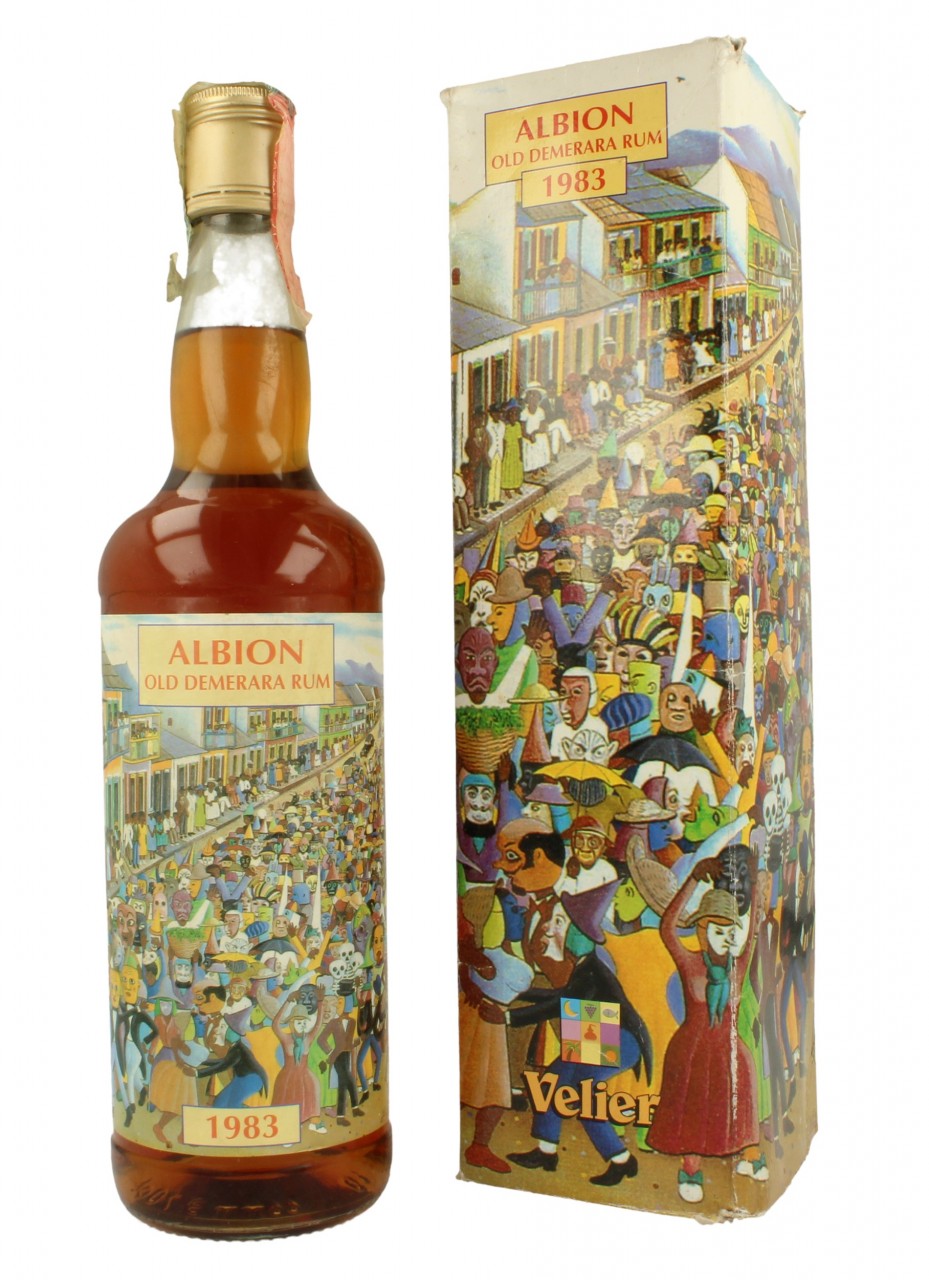

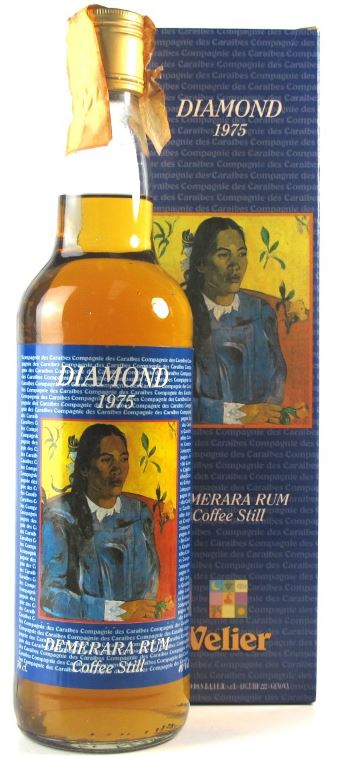

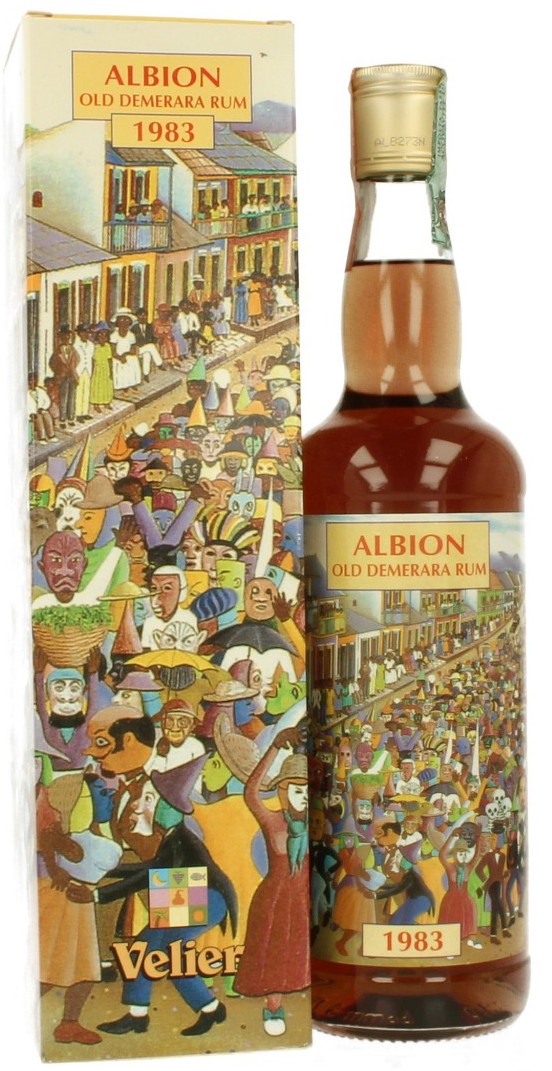

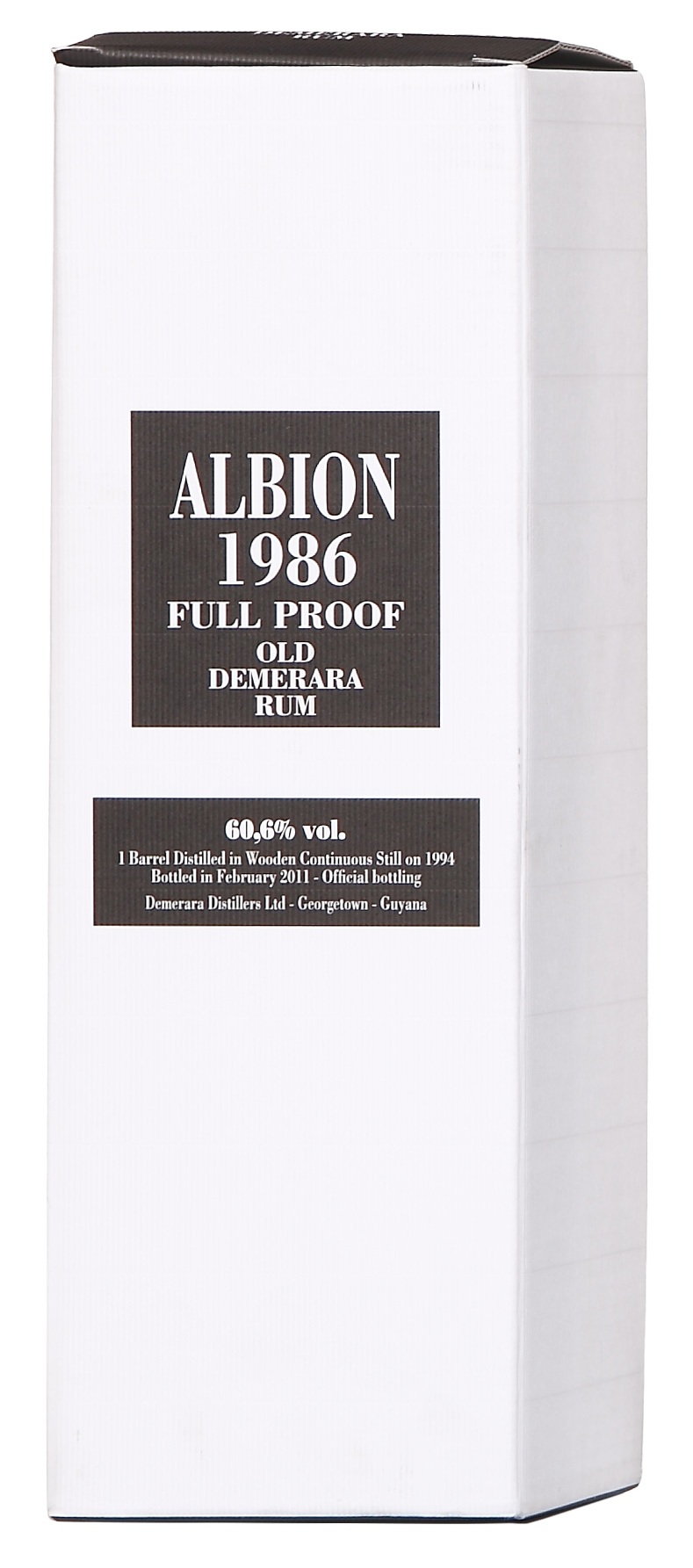

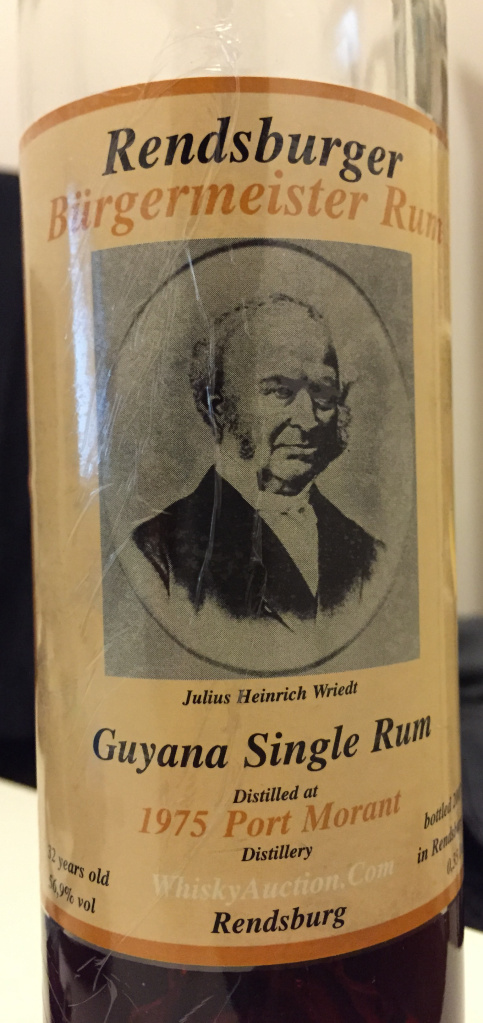

2007 was an odd year, when everything issued was under ten years old, which may just have been a function of what was put in front of Luca to inspect and select. The first Versailles rum since 1996 was issued in 2007, and somehow another LBI rum was found – it would prove to be the last. When it came to releases, 2008 was a banner year for the company, when eight Demerara rums were issued at once. Yet widespread acceptance remained elusive: costing out at over a hundred euros per bottle, most consumers in Europe, where distribution was primarily limited, felt this was still to expensive (bar the Italians, who I was told were snapping them up). One can only imagine how frustrating this must have been to Luca, who knew how good they were. The standouts from this year’s collection were undoubtedly those amazing 1970s Port Mourants, which are now probably close to priceless, if they can even be found. (And even the others are becoming grail quests – I saw an online listing in June 2018 for the Albion 1983, at close to two thousand euros).

When it came to releases, 2008 was a banner year for the company, when eight Demerara rums were issued at once. Yet widespread acceptance remained elusive: costing out at over a hundred euros per bottle, most consumers in Europe, where distribution was primarily limited, felt this was still to expensive (bar the Italians, who I was told were snapping them up). One can only imagine how frustrating this must have been to Luca, who knew how good they were. The standouts from this year’s collection were undoubtedly those amazing 1970s Port Mourants, which are now probably close to priceless, if they can even be found. (And even the others are becoming grail quests – I saw an online listing in June 2018 for the Albion 1983, at close to two thousand euros). Something interesting happened in 2010, overlooked by many, ignored by the rest. For the first time reviews of the Velier Demeraras start to appear in the blogosphere, and they were all from Serge Valentin of Whiskyfun. He had

Something interesting happened in 2010, overlooked by many, ignored by the rest. For the first time reviews of the Velier Demeraras start to appear in the blogosphere, and they were all from Serge Valentin of Whiskyfun. He had  2011 was another skinny year, with only three rums being released, two of which were from Albion. Why DDL would sell off barrels of defunct distilleries like LBI, Blairmont or Albion is a curious window into their commercial mindset at the time – it’s possible that they simply didn’t see any margins in such niche products which might cost more to bring to market than they would sell for, though Velier clearly showed this was not so. Since Velier maintained a low profile outside Italy, they probably didn’t see such rums adding value to the DDL brand, and were okay letting them go.

2011 was another skinny year, with only three rums being released, two of which were from Albion. Why DDL would sell off barrels of defunct distilleries like LBI, Blairmont or Albion is a curious window into their commercial mindset at the time – it’s possible that they simply didn’t see any margins in such niche products which might cost more to bring to market than they would sell for, though Velier clearly showed this was not so. Since Velier maintained a low profile outside Italy, they probably didn’t see such rums adding value to the DDL brand, and were okay letting them go.

Nothing was issued in 2013 (the reasons remain obscure), and b

Nothing was issued in 2013 (the reasons remain obscure), and b

The rum world in the 1980s was a rather staid one, moving along very much as it had for years before. Major rum companies from around the Caribbean were issuing more or less the same rums they had been for decades – then as now, 40% ABV was practically a standard, age almost uniformly under ten years (if mentioned at all), and the market was full of familiar brands, similar recipes, incremental development, and with column still blends being the majority of sales.

The rum world in the 1980s was a rather staid one, moving along very much as it had for years before. Major rum companies from around the Caribbean were issuing more or less the same rums they had been for decades – then as now, 40% ABV was practically a standard, age almost uniformly under ten years (if mentioned at all), and the market was full of familiar brands, similar recipes, incremental development, and with column still blends being the majority of sales.

Aged rums made by primary producers from the pre-1990s eras were on the market, sure, and there was no shortage of them….but one had to look carefully for the specific trees in the forest (nowadays even more so when most exist in private collections or in memory alone).

Aged rums made by primary producers from the pre-1990s eras were on the market, sure, and there was no shortage of them….but one had to look carefully for the specific trees in the forest (nowadays even more so when most exist in private collections or in memory alone).  Anyway, much of the primary producers’ rum production went to Europe in bulk (a lot went to E&A Scheer, which was and remains one of the largest brokers buying rum stock in the world) and was then blended into European producers’ rums, of which there were many, none of which achieved any sort of lasting fame (unless it was the navy style of rum made by UK companies like Watsons for the local market). There were many small merchant bottlers, shops and back-street independents who released extremely limited and now-often-forgotten bottlings of aged expressions into the marketplace. And so the West Indian distilleries consolidated, shuttered, closed, changed focus, modernized, diversified, found new markets…and somehow the rum continued to flow.

Anyway, much of the primary producers’ rum production went to Europe in bulk (a lot went to E&A Scheer, which was and remains one of the largest brokers buying rum stock in the world) and was then blended into European producers’ rums, of which there were many, none of which achieved any sort of lasting fame (unless it was the navy style of rum made by UK companies like Watsons for the local market). There were many small merchant bottlers, shops and back-street independents who released extremely limited and now-often-forgotten bottlings of aged expressions into the marketplace. And so the West Indian distilleries consolidated, shuttered, closed, changed focus, modernized, diversified, found new markets…and somehow the rum continued to flow. What made the

What made the

A word should be spared for the work of the Martinique and Guadeloupe rum producers which don’t conform to the title of independents, but which also laid some of the groundwork for the renaissance of strong and singular rums that was about to take off. These small estate distilleries sold their rums primarily on the local market and exported to France through their own distribution arms there. Among all their lightly aged rums and blends and whites, they also and occasionally produced

A word should be spared for the work of the Martinique and Guadeloupe rum producers which don’t conform to the title of independents, but which also laid some of the groundwork for the renaissance of strong and singular rums that was about to take off. These small estate distilleries sold their rums primarily on the local market and exported to France through their own distribution arms there. Among all their lightly aged rums and blends and whites, they also and occasionally produced

But there was a sixth principle, not often stated, yet deeply held. And that was that food and drink should be as natural as possible, organic, free from the interferences of technology, fresh from the land. When one applies that to food it’s one thing, but few before him sought to apply the concept to rums (except perhaps out of necessity). He felt that rum should be bottled as it either came off the stills or out of the ageing barrel without further messing around. He may have known more than we did in those more innocent times, because although it is now common knowledge that many old favourites which came to the market in the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s were dosed with additives, back in the day there was a lot more trust going around between consumers and producers.

But there was a sixth principle, not often stated, yet deeply held. And that was that food and drink should be as natural as possible, organic, free from the interferences of technology, fresh from the land. When one applies that to food it’s one thing, but few before him sought to apply the concept to rums (except perhaps out of necessity). He felt that rum should be bottled as it either came off the stills or out of the ageing barrel without further messing around. He may have known more than we did in those more innocent times, because although it is now common knowledge that many old favourites which came to the market in the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s were dosed with additives, back in the day there was a lot more trust going around between consumers and producers.

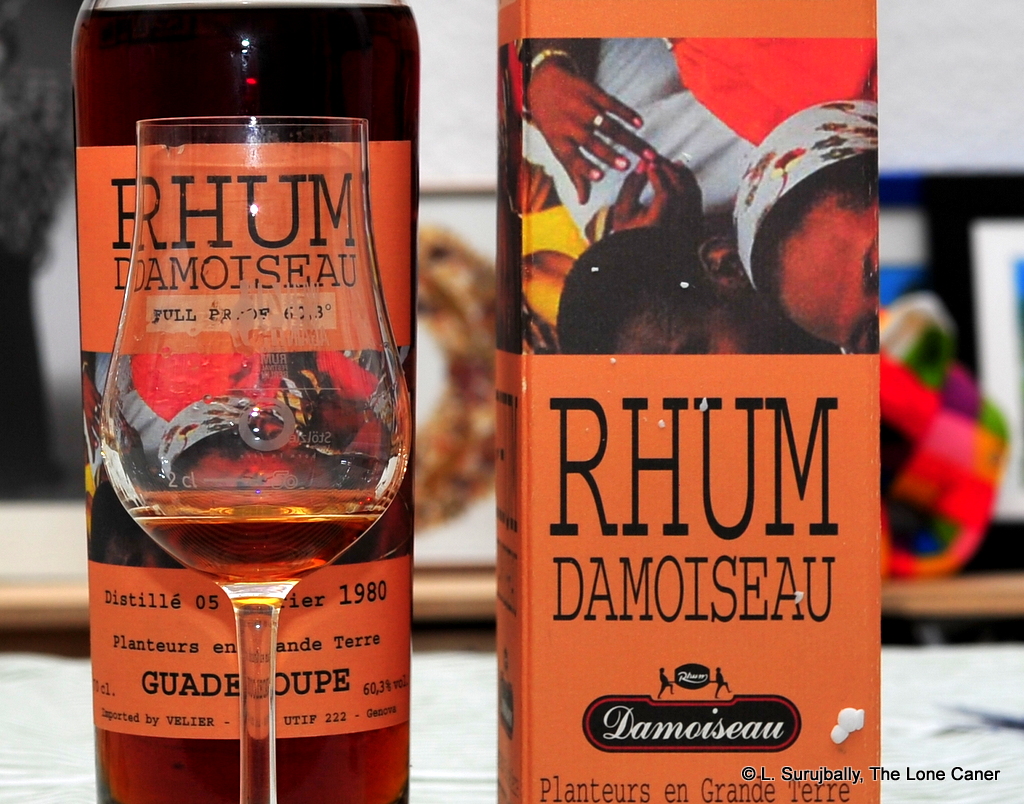

He was still wrestling with whether this was a workable commercial concept when he found a stored 18 year old rum at Damoiseau in Guadeloupe which was so spectacular, that he released it at 60.3% ABV in 2002, crossing his fingers as he did so. The success of the

He was still wrestling with whether this was a workable commercial concept when he found a stored 18 year old rum at Damoiseau in Guadeloupe which was so spectacular, that he released it at 60.3% ABV in 2002, crossing his fingers as he did so. The success of the