Shochu, along with awamori, is the oldest distilled spirit made in Japan, just about all of it in the south island of Kyushu and its surrounding islands, and so distinct that several varieties have their own geographical protections. It’s versatile, interesting, very drinkable, and is becoming even more popular than sake in the last years, especially in Japan, where most of it is consumed. And while the focus of my work is rum, and the point of this article is to highlight local spirits based on sugar cane, I must be clear that the cane spirit known as kokuto shochu is just one sub-type of the spirit.

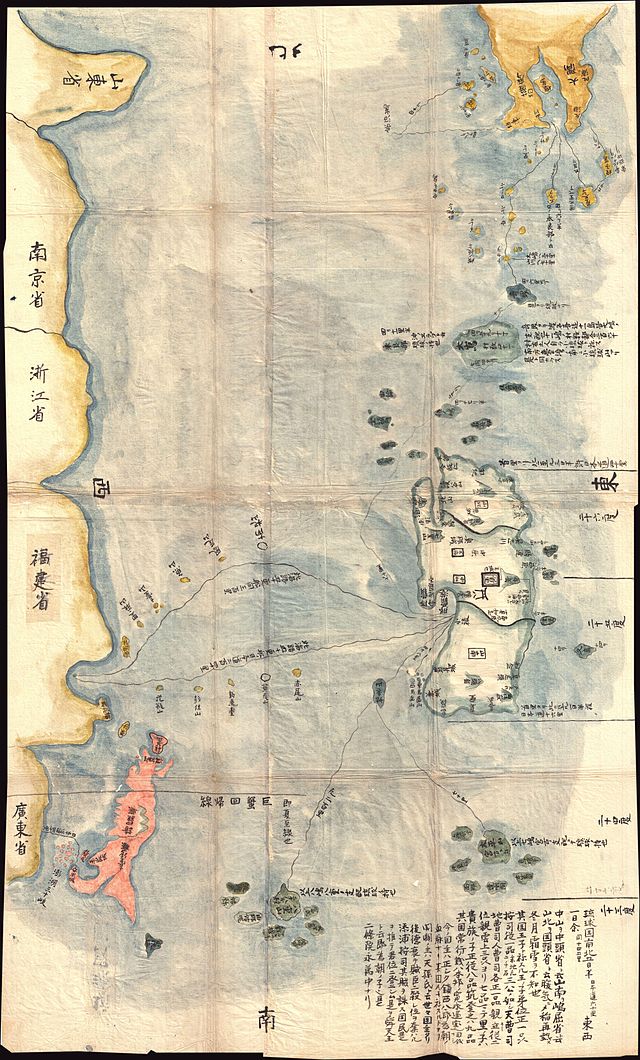

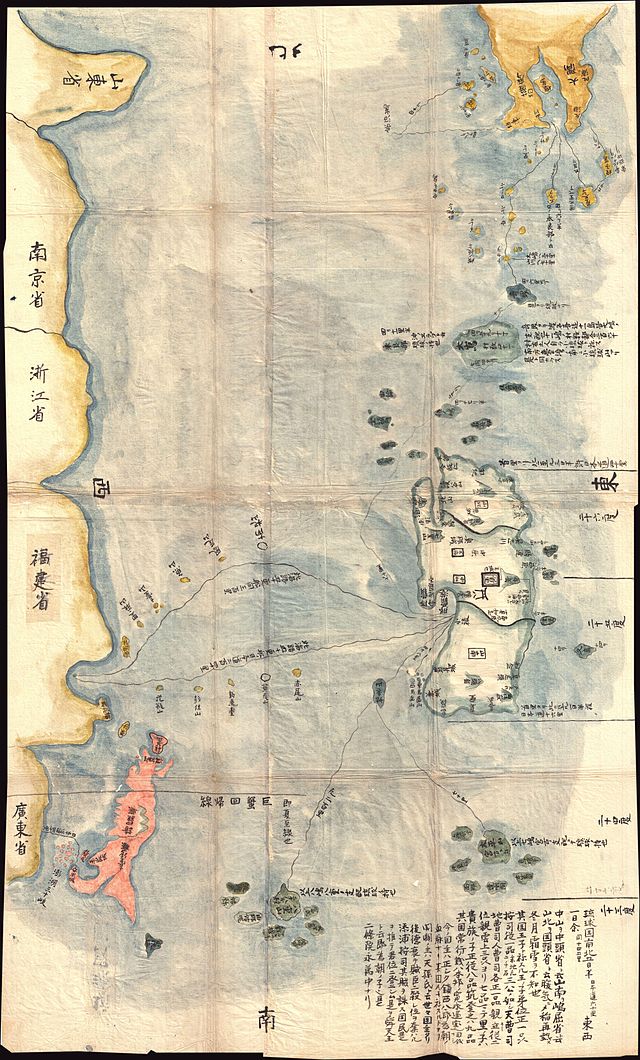

1781 Map showing southern Kyushu and Ryukyu Islands (c) wikiwand.com

History

Scholars dispute whether the art of distillation came from Korea (due to similarities in distillation technology) or from Okinawa (liquor shipping records from the 1500s detailing cargoes from Okinawa to Japan date back at least that far), but in general it’s acknowledged that both routes are valid, and the only real unknown is which came first. Distillation technology appears to have been spread widely via the robust China sea trade in the late 1400s onward; and there was a brisk trade between Korea and Japan at that time that disseminated knowledge quickly.

Initially shochu appears to have been something of a rural spirit, made by fishermen at first, then moving inland to farmers and home brewers and this continued from its origin in the 1500s, through the duration of the Tokugawa shogunate. This is possibly one of the reasons why so many raw ingredients can be used and still be titled shochu, because until the Meiji Restoration in 1868 there was little or no regulation – the Restoration brought in formalization of rules, licenses and some measure of quality control (and of course taxation).

Most shochu was authentic or honkaku shochu – we might call it artisanal today – until the early 1900s when the adoption of industrial column stills led to the rise of a second style called korui. This is essentially mass produced alcohol close to 96% ABV off the still, which is then diluted down to below 36% (around 20% or so seems to be common), and is sold as a catch-all alcoholic drink, like an ersatz vodka – it is this variation which is closest to the similarly mass-produced, cheap, diluted and near-ubiquitous Korean soju.

Honkaku shochu, for all its cachet as an artisanal spirit now, was for centuries considered a local drink not traded anywhere and only found in Japan; indeed, until the 1970s even within Japan it was considered something of a blue-collar worker’s tipple limited to, and almost all consumed in, the southern island of Kyushu and its surrounding islands.

Benisango kokotu shochu. Photo (c) Whiskey Richard at Nomunication.jp

Basics

First of all, shochu is a distilled alcohol, not made like and completely distinct from nihonshu, or sake (which is brewed like beer is, though it is not a beer itself); it shares close kinship with another uniquely Japanese spirit from Okinawa called awamori, while having its own special rules that make it, again, distinct (shochu is very much defined by how it’s made, not from what); honkaku shochu has no real relationship with the Korean drink soju (unless it’s the barely known traditional Andong soju) and should never be confused with it; and like aguardientes of the Americas, many different raw materials can be used to make shochu (fifty-plus, by some estimates), including but not limited to barley, buckwheat, sake lees, rice, sweet potatoes, kelp, green tea, flowers, mushrooms…and sugar cane. Each has its own peculiarities and naming conventions, and because this is not a primer on shochu as a whole — there are other, better and more in-depth sources and wikipedia for the curious deep divers — I must keep things brief, refer you to the “sources”, below for further reading, and will concentrate most of this article on the one variation that is made from sugar cane: kokuto shochu.

Fermentation

The above points aside, several aspects of the drink are common to all varieties. All shochus have a dual fermentation system (awamori only has one, which is one of the main dividers separating the two classes of drinks): one fermentation converts starches into sugars and the other converts these sugars into alcohol. These are really multiple parallel fermentations, and starch conversion and fermentation to alcohol occur simultaneously from start to finish. Both use one of several kinds of a mold (fungus) called koji, which is also utilized in the making of soy sauce, miso, rice vinegars, sake and awamori, and the type of koji used has a discernible impact on the final flavour of the resultant shochu.

Kokuto means ‘brown,’ ‘black’ or ‘dark’ sugar (sources vary as to which is the true and exact meaning) and is akin to jaggery of India, or the panela of Latin America; now, since shochu deriving from sugar directly doesn’t require that first fermentation pass given that the base alcohol source (sugar) is already in existence, it would seem to be an irrelevant step — but in Japanese tax law, to be called kokuto shochu, the first fermentation must happen, and must happen with rice koji. Failing that, the product must be classified and taxed as some other distilled spirit, like rum. Indeed, leaving out the first step is what the Ogasawara Islands did in the pre-war years when they first experimented with brown sugar shochu using a single fermentation cycle — but the war shut down production and by the time they restarted, the tax law had come into effect and they simply resorted to calling it rum, one of which I’ve actually tried.

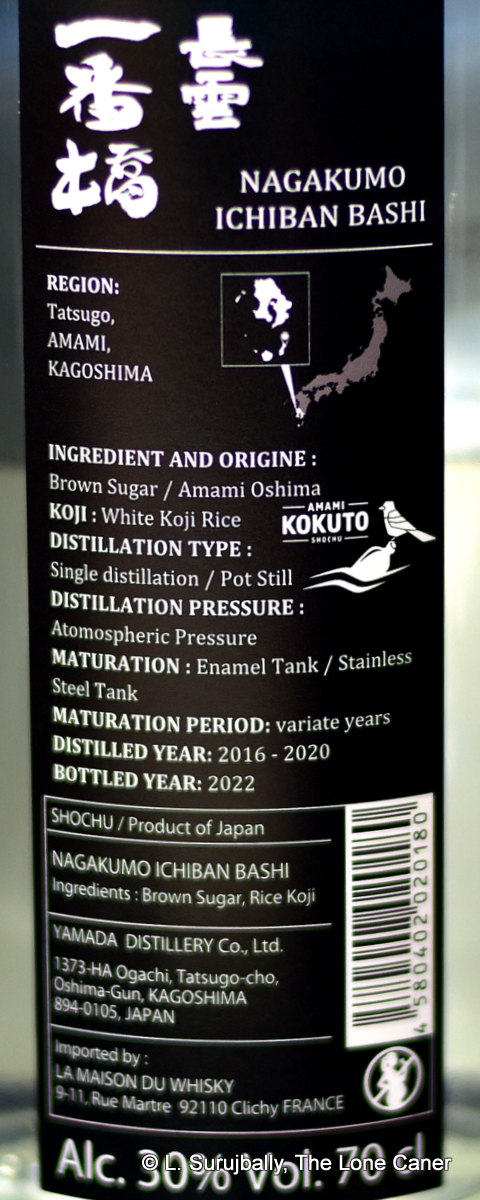

Photo from wikimedia commons

Distillation

Shochus can be distilled in either multiple passes or single ones, and the type of still is not a disqualifier (though it can be a restriction). Multiple distillations from high efficiency columnar stills result in a more odorless high-proof spirit and is classified as korui shochu, “Class A” but it’s important to understand that this class is about process, and unrelated to quality. Korui shochus are usually made from molasses, potatoes or corn, and are distilled to 95% or greater and then diluted down to below 36%, always in large capacity distilleries – in that it has similarities with cheap rums around the world.

The more interesting variations of the spirit — at least from my own perspective, given my interest in more artisanal cane spirits — are the Class B (Otsurui) shochus which are all the honkaku shochus. As with Class A, the most common base ingredients are rice, cane, barely, sweet potatoes, etc. After fermentation they are – and must be, by law – distilled only once, and only in pot stills. In the old days, many of these stills, especially in the smaller distilleries, were actually made of wood, including cedar (take that, DDL), but this is rare nowadays. Given the single distillation methodology and the still itself, the flavours are bursting out, even at the low strength at which it comes off – 45% ABV or less (if it were more it would no longer be honkaku and the tax breaks would not be applicable). For the rum aficionado, the drink is, essentially, almost tailor-made for taking neat, though it should be stated clearly that in Japan it’s usually diluted or drunk on the rocks.

Ageing

As with rum, the ageing of shochu can be short, medium or long: however, in a divergence from artisanal white rums which have such a strong presence in the rum world, completely unaged shochu is rare. Shochu can be rested or aged in steel tanks, clay pots, wooden barrels or large wooden casks – once it was rare for ageing to exceed three years, because then, especially with wooden casks of any kind, the shochu would get too dark and thus be deemed a whisky, with its attendant and different tax regime. However, in the last two decades this limit has been far exceeded, because at the three year point the shochu could then be labelled as koshu or “old alcohol” and can be sold for a higher price. There are now shochus as old as thirty years on the market (not necessarily aged in oak, mind you), almost all sold only in Japan.

As an interesting side note, ageing is not always or only done in warehouses or temperature-controlled buildings as is common elsewhere in the rum world, but occasionally in caves, tunnels and limestone caverns where variations in temperature and humidity are kept to a minimum. This is probably just a matter of available space, climate control and geographical convenience, rather than any kind of cultural tradition, but Stephen Lyman remarked to me that it is actually preferred by shochu makers, and some even excavate their own underground caverns to age their stocks.

Kokuto sugar (c) Chris Pellegrini, kanpai.us

Kokuto shochu specifically

Kokuto shochu therefore has all the above aspects in common with the other base-material varietals. It is, however, indigenous to and identified completely and only with the Amami islands off the coast of Kagoshima (between Kyushu and Okinawa, in the south of Japan) where there has been a long history of producing it from locally grown cane. So much so, in fact, that it is the recipient of a Geographical Indicator of its own. Amami kokuto shochu is made in any of 28 distilleries there, spread out over five islands and cannot legally be made anywhere else.

Originally part of the Ryukyu Kingdom of Okinawa, they were taken over by the more powerful southern Satsuma Domain in 1609, and turned the islands into one huge sugar cane plantation. For centuries they repressively discouraged the use of the valuable sugar being turned into alcohol (which could lead to – horrors! – losing revenue and distracting the workforce), but the privations of the post-war period when all rice was diverted from alcohol-making to a food source, brought kokuto sugar distillate out of the shadows and kokuto shochu gained some legitimacy at last.

For reasons to do with surplus stocks, politics and tax law in these post-WW2 years, special recognition was given to this type of shochu as ‘brown sugar shochu’ (so long as they used rice koji, and two fermentation passes) to develop the industry and the local region. The spirit remains thus recognized to this day, and is generally bottled at around 25-30% ABV (tax laws change at 25% for most shochus so that has become a sort of unofficial standard elsewhere, but kokuto shochu received a tax break for stronger versions that lasted until 2008, so 30% is more common there).

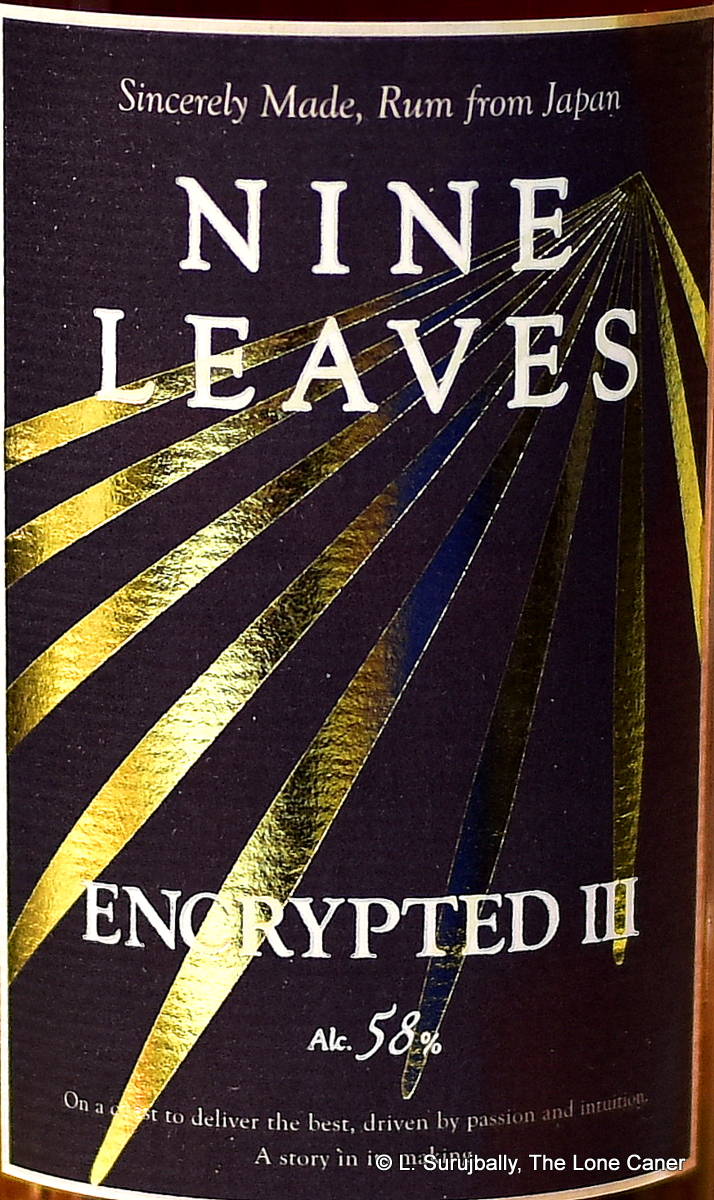

Aside from the requisite two-pass fermentation and use of rice koji, kokuto shochu is also different from regular rum in one other respect – it can only be made from (a) kokuto sugar, which is unrefined sugar very high in mineral content (i.e., without any molasses removed or added back in as may be the case in the west), or (b) blocks of dried molasses deriving from that sugar, that are added to the rice-koji ferment for the second fermentation. So, no cane juice, no gooey molasses, no rendered sugar cane “honey”. If a Japanese distillery used any of these materials, a different tax law would govern production, and it would be classified as rum or a liqueur – and indeed, in the interests of expediency, those few rum makers as do exist in Japan, prefer to go this route and produce what we would see as “traditional” rum like Cor Cor, Ogasawara, Ryomi, Nine Leaves, etc..

Photo CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sales

Kokuto shochu (as are all other kinds) is mostly drunk within Japan and is not widely known outside it. Some eastern- and western-seaboard US states carry it, and there is a store in Berlin called Ginza (closed currently due to COVID) that I was unable to buy from, or visit to taste what they had. I imagine there are more out there. However, for the moment, the good stuff, the best stuff, all remains in Japan and is mostly consumed there.

Wrap up

Rum lovers are often fixated on just a few areas of the world: the Caribbean and South/Latin America; the new distilleries in Europe, the UK, and North America; and micro distilleries in Asia and the Pacific, plus the occasional nod to big ass industrial conglomerates like Tanduay and McDowell’s. South Pacific Distillers and some of the Pacific Islands are getting some traction. But underneath all these well known places and names coil smaller operations, artisanal ones that have a tradition far more interesting, and far older. They produce what is recognizably rum in a form that is distinct and interesting and broadens the understanding of the sugar cane spirit. Shochu is one of these, and it worth seeking out.

Reviewed Kokuto Shochus

Other Notes

- “Macrons” have been removed from transliterations of Japanese words used here, e.g. kokutō, kōji, and shōchū.

- This article is meant as an introduction only, since the field of Japanese spirits – even if restricted to just cane-based ones – is huge (and fascinating). Sources, below, provide additional recommendations for reading.

Sources

- For background materials and education, I am deeply indebted to the conversations and emails I have traded with Stephen Lyman and Christopher Pellegrini, who have written extensively on Japanese spirits. They are the authors of, respectively, “The Complete Guide to Japanese Drinks” and “The Shochu Handbook – An Introduction to Japan’s Indigenous Spirit” both of which I read in preparation for this article and recommend highly, and from which aspects of the above essay were sourced. They also run the very informative podcast “Japan Distilled” which is required listening for me these days. I have drawn freely from the well of their combined experience, publications, discussions and education. Plus, they’re just great guys — friendly, informed, helpful.

- December 2021 “Seven Fifty Daily” article on Shochu by Steve & Chris

- August 2020 “Nomunication” article on Kokuto Shochu

- Wikipedia on Shochu and kokuto shochu

- Wikipedia on Awamori

- California Laws and naming confusion between shochu and soju

- Japan Distilled Podcast Episodes and Episode 15 on kokuto shochu.

- John Go’s Malt Review article on Tomoet Moi kokuto shochu

- Nico’s March 2022 article for Compagnie des Indes on whether shochu was a coming thing

- Facebook articles

- Sake School of America brief notes

- August 2020 A list of Amami Islands kokuto shochu distilleries

- August 2020 Kanpai article on kokuto sugar

- There’s a subreddit for the curious…

- Nonjatta has a good introduction to shochu as a whole, including a useful vocabulary and label reading primer. Written in 2006, but not dated at all.

production. They are probably better known in Japan for their awamoris, shochus and beers, but for our purposes, it’s the rums that excite attention.

production. They are probably better known in Japan for their awamoris, shochus and beers, but for our purposes, it’s the rums that excite attention. Tasting it makes for a better experience, much better – the rum turns a little sweet, with fewer potatoes (although the scent and taste persist). Again, you can taste sweet soya, vanilla, smoke, celery, prunes, figs and some lemongrass-infused soup, and yes, that pimento is still there. It all leads to a comfortable finish which sums things up with some soup, salt, celery and prunes, not a lot else.

Tasting it makes for a better experience, much better – the rum turns a little sweet, with fewer potatoes (although the scent and taste persist). Again, you can taste sweet soya, vanilla, smoke, celery, prunes, figs and some lemongrass-infused soup, and yes, that pimento is still there. It all leads to a comfortable finish which sums things up with some soup, salt, celery and prunes, not a lot else.

The nose rather interestingly presented hints of a funky kind of fruitiness at the beginning (like a low rent Jamaican, perhaps), while the characteristic clarity and crisp individualism of the aromas such as the other Nine Leaves rums possessed, remained. It was musky and sweet, had some zesty citrus notes, fresh apples, pears and overall had a pleasing clarity about it. Plus there were baking spices as well – nutmeg and cumin and those rounded out the profile quite well.

The nose rather interestingly presented hints of a funky kind of fruitiness at the beginning (like a low rent Jamaican, perhaps), while the characteristic clarity and crisp individualism of the aromas such as the other Nine Leaves rums possessed, remained. It was musky and sweet, had some zesty citrus notes, fresh apples, pears and overall had a pleasing clarity about it. Plus there were baking spices as well – nutmeg and cumin and those rounded out the profile quite well.