Distilleries that go off on their own tangent are always fun to watch in action. They blend a wry and deprecating sense of humour with a quizzical and questioning mien and add to that a curiosity about the rumiverse that leads to occasional messy road kill, sure…but equally often, to intriguing variations on old faithfuls that result in fascinating new products. Killik’s Jamaican rum experiments come to mind, and also Winding Road’s focus on their cane juice based rums1, like they were single handedly trying to do agricoles one better.

Moving on from the standard proofed rums from Australia upon which the focus has been directed over the last weeks, we begin to arrive at some of those that take the strength up a few notches, and when we bring together a higher proof with an agricole-style aged rum — as uncommon in Australia as almost everywhere else — it’s sure to be interesting. Such ersatz-agricoles rums are the bread and butter of the Winding Road Distilling Co in New South Wales (about 175km south of Brisbane), which is run by the husband and wife team of Mark and Camille Awad: they have two rums in their small portfolio (for the moment), both cane-juice based. The first, the Agricole Blanc was an unaged rum of this kind, one with which I was quite taken, and it’s the second one we’re looking at today.

It’s quite an eye-opener. Coastal Cane Pure Single Rum is rum with the source cane juice coming from a small mill in the Northern Rivers area (where WR are also located), and as far as I know is run through the same fermentation process as the blanc: three days in open vats using both commercial and wild yeasts, with the wash occasionally left to rest for longer (up to two weeks). Then the wash is passed — twice — through their 1250 litre pot still (called “Short Round”) and set to age in a single 200-litre American oak barrel with a Level 3 char, producing 340 bottles after 31 months. Bottling is then done at 46% in this instance: that, however, will change to suit each subsequent release based on how it samples coming out of the ageing process.

It’s quite an eye-opener. Coastal Cane Pure Single Rum is rum with the source cane juice coming from a small mill in the Northern Rivers area (where WR are also located), and as far as I know is run through the same fermentation process as the blanc: three days in open vats using both commercial and wild yeasts, with the wash occasionally left to rest for longer (up to two weeks). Then the wash is passed — twice — through their 1250 litre pot still (called “Short Round”) and set to age in a single 200-litre American oak barrel with a Level 3 char, producing 340 bottles after 31 months. Bottling is then done at 46% in this instance: that, however, will change to suit each subsequent release based on how it samples coming out of the ageing process.

Mark Awad’s avowed intention is to produce a distillate that combines the clarity of agricole rhums with a touch of the Jamaican badassery we call hogo, as well as representing, as far as possible, the terroire of NSW…specifically Northern Rivers, where they are. I can’t tell whether this is the rum that accomplishes that goal, but I can say it’s very good. The nose is lovely, starting with deep dark fruits (prunes and blackberries), opens up to lighter notes (bananas, oranges and pineapples) covered over with unsweetened yoghurt and feta cheese. There’s a nice low-level funkiness here that teases and dances around the aromas without the sort of aggressiveness that characterises the Jamaicans, combined with floral hints and – I swear this is true – smoke, wet ashes, and something that reminds me of the smell on your fingers left behind by cigarettes after smoking in very cold weather.

The barrel influence is clear on the palate – vanilla, some light caramel and toffee tastes are reminders that it’s not an unaged rum. But it’s also quite dry, not very sweet in spite of the lingering notes of lollipops and strawberry bubble gum, has flavours of brine and lemon-cured green Moroccan olives, and brings to mind something of a Speysider or Lowland whisky that’s been in a sherry cask for a bit. It’s one of those rums that seems simple and quiet, yet rewards patience and if allowed to open up properly, really impresses. Even the finish has that initially-restrained but subtly complex vibe, providing long, winey closing notes together with very ripe blue grapes, soft apples, brine, and a touch of lemony cumin.

I’m really intrigued with what Winding Road have done here. With two separate rums they have provided taste profiles that are quite divergent, enough to seem as if they were made by different companies altogether. There are aspects of this aged rum that are more pleasing than the unaged version, while others fall somewhat behind: I’d suggest the nose and the finish is better here, but honestly, they are both quite good, just in different ways.

The constant tinkering and experimentation that marks out these small Australian distilleries — who strive to find both their niche and that point of distinction that will set them apart — clearly pays dividends. While I can’t tell you with assurance I tasted an individualistic terroire that would lead me straight to NSW (let alone Australia), neither did the Awads head into the outback at full throttle, going straight through the wall leaving only an outline of themselves behind. What they have in fact accomplished is far better: they have created a rum that is thoroughly enjoyable, one that takes a well known style of rum, twists it around and bounces it up and down a bit…and ends up making the familiar new again. I can’t wait for Release #2.

(#911)(85/100) ⭐⭐⭐½

Other notes

- The website specs refer to a single 200-litre barrel and the initial math seems wrong if 340 700-ml bottles were issued (since that works out to 238 litres with zero evaporation losses). However, that only computes if you assume the distillate went in and came out at the same strength. Mark confirmed: “The figures on our website are correct, even though at first glance they may seem a bit off. We filled the barrel at 67.1% ABV and when it was decanted the rum came in at 65.1%. We ended up with just short of 169 litres which we then adjusted down to 46% ABV. This gave us a bit over 239 litres which resulted in 340 bottles, plus a little extra that went towards samples.”

- As always, chapeau to Mr. and Mrs. Rum for their kind supply of the advent calendar.

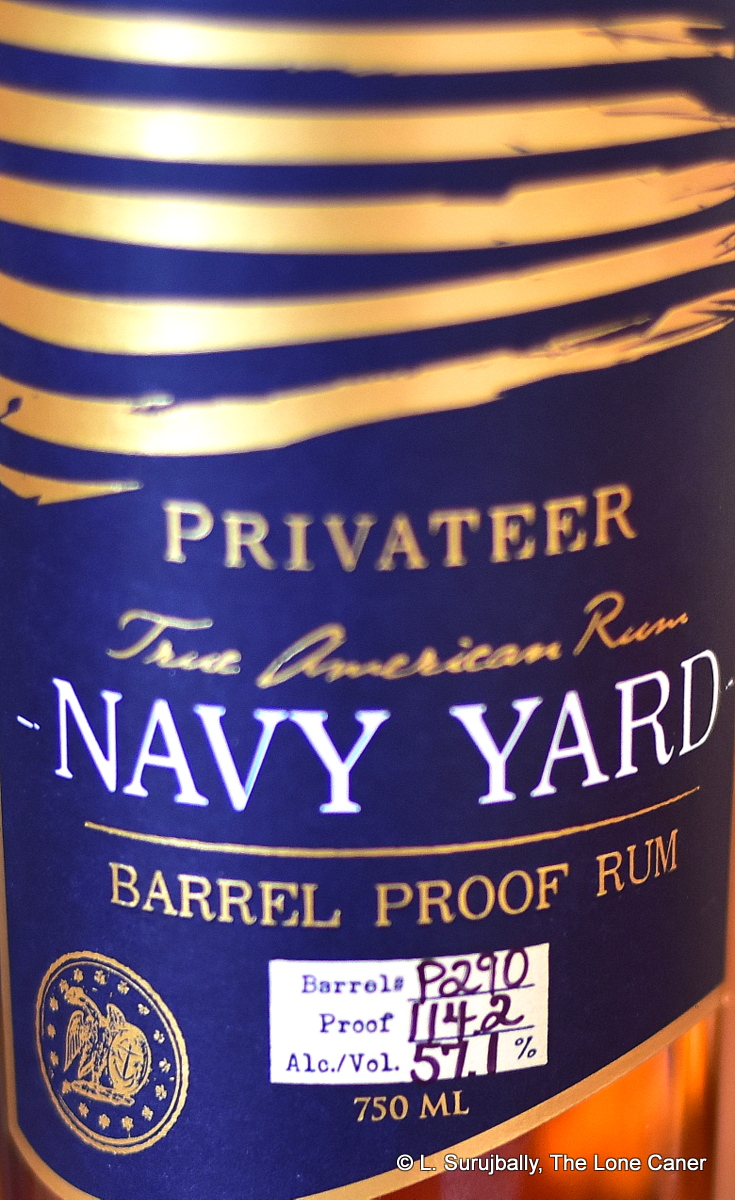

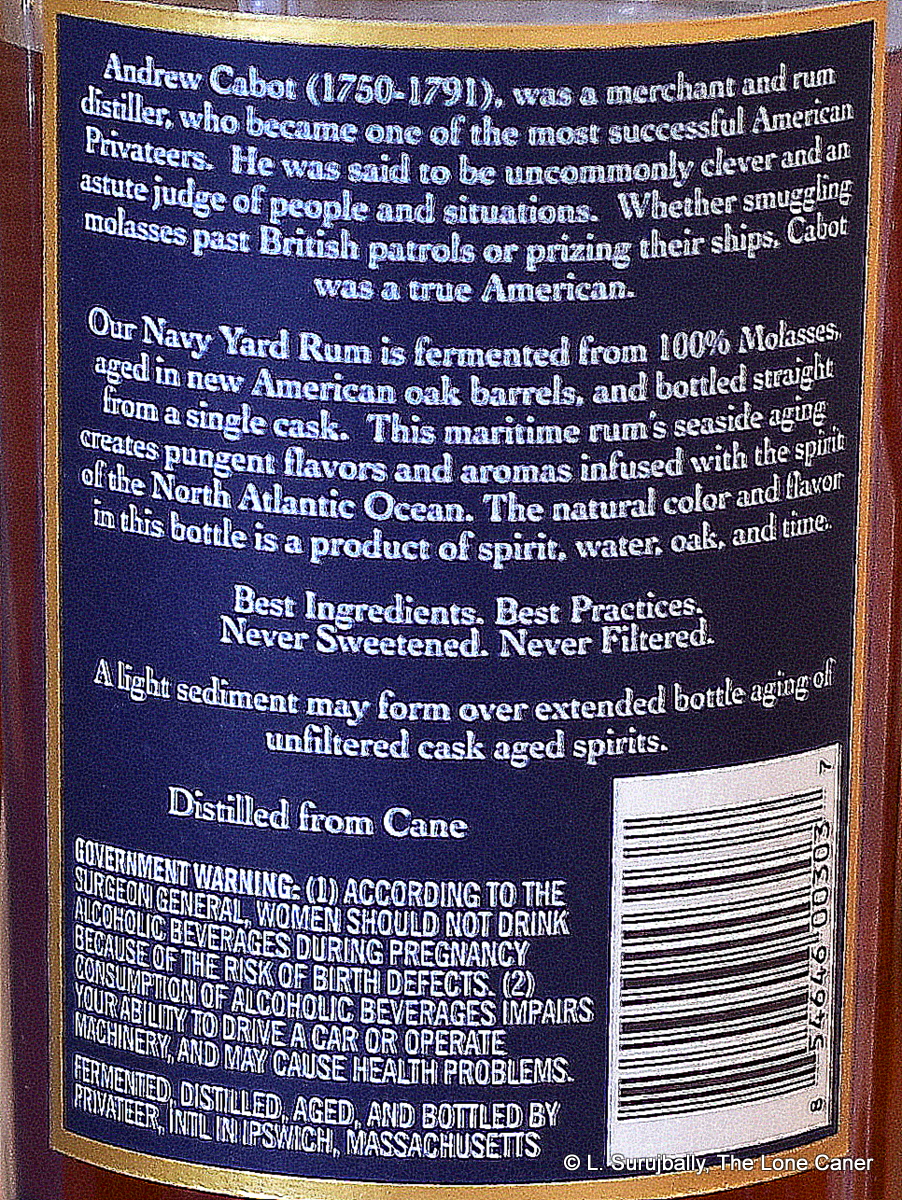

Privateer

Privateer Overall, it’s a good young rum which shows its blended philosophy and charred barrel origins clearly. This is both a strength and a weakness. A strength in that it’s well blended, the edges of pot and column merging seamlessly; it’s tasty and strong, with just a few flavours coming together

Overall, it’s a good young rum which shows its blended philosophy and charred barrel origins clearly. This is both a strength and a weakness. A strength in that it’s well blended, the edges of pot and column merging seamlessly; it’s tasty and strong, with just a few flavours coming together