It’s been many years since the first of those blended dark-coloured UK supermarket rums dating back decades crossed my path – back then I was writing for Liquorature, had not yet picked up the handle of “The ‘Caner”, and this site was years in the future. Yet even now I recall how much I enjoyed Robert Watson’s Demerara Rum, and I compared it positively with my private tippling indulgence of the day, the Canada-made Young’s Old Sam blend — and remembered them both when writing about the Wood’s 100 and Cabot Tower rums.

All of these channelled some whiff of the old merchant bottlers and their blends, or tried for a Navy vibe (not always successfully, but ok…). Almost all of them were (and remain) Guyanese rums in some part or all. They may be copying Pusser’s or the British heritage of centuries past, they are cheap, drinkable, and enjoyable and have no pretensions to snobbery or age or off-the-chart complexity. They are a working man’s rums, all of them.

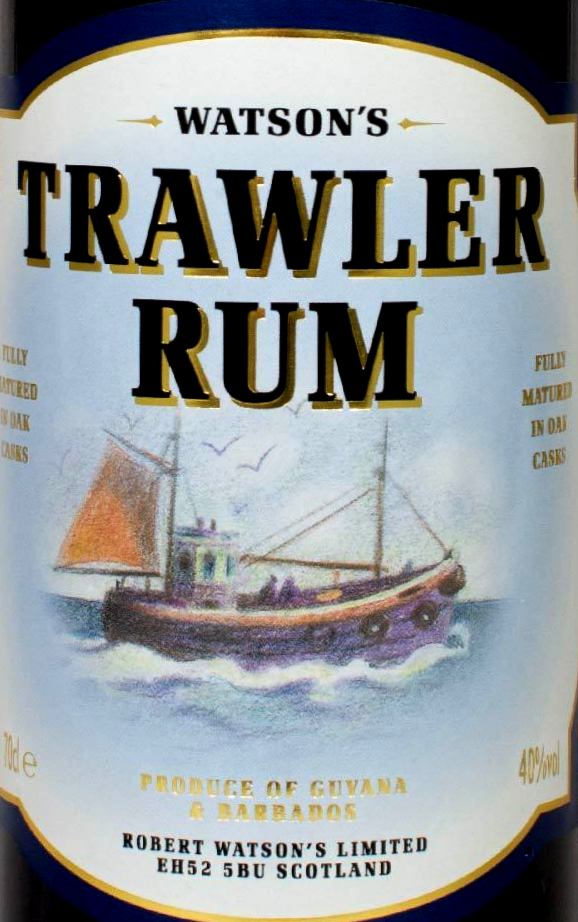

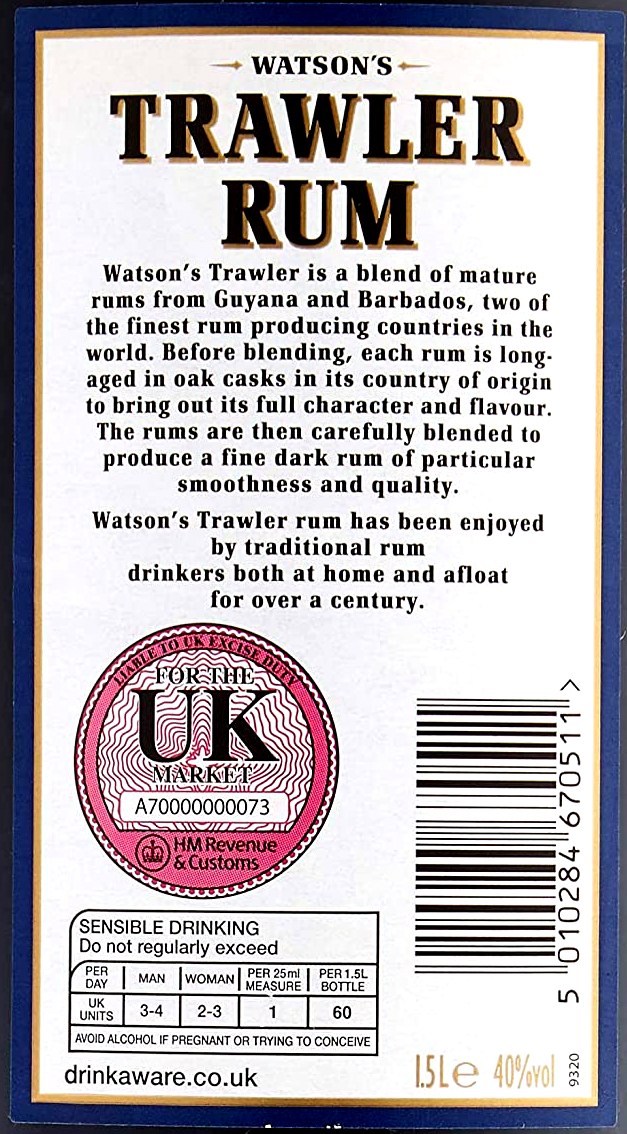

Watson’s Trawler rum, bottled at 40% is another sprig off that branch of British Caribbean blends, budding off the enormous tree of rums the empire produced. The company, according to Anne Watson (granddaughter of the founder), was formed in the late 1940s in Aberdeen, sold at some point to the Chivas Group, and since 1996 the brand is owned by Ian McLeod distillers (home of Sheep Dip and Glengoyne whiskies). It remains a simple, easy to drink and affordable nip, a casual drink, and should be approached in precisely that spirit, not as something with pretensions of grandeur.

Watson’s Trawler rum, bottled at 40% is another sprig off that branch of British Caribbean blends, budding off the enormous tree of rums the empire produced. The company, according to Anne Watson (granddaughter of the founder), was formed in the late 1940s in Aberdeen, sold at some point to the Chivas Group, and since 1996 the brand is owned by Ian McLeod distillers (home of Sheep Dip and Glengoyne whiskies). It remains a simple, easy to drink and affordable nip, a casual drink, and should be approached in precisely that spirit, not as something with pretensions of grandeur.

I say “simple” and “easy” but really should also add “rich”, which was one of the first words my rather startled notes reveal. And “deep.” I mean, it’s thick to smell, with layers of muscovado sugar, molasses, licorice, and bags of dark fruits. It actually feels more solid than 40% might imply, and the aromas pervade the room quickly (so watch out, all ye teens who filch this from your parents’ liquor cabinets). It also smells of stewed apples, aromatic tobacco, ripe cherries and a wedge or two of pineapple for bite. Sure the label says Barbados is in the mix, but for my money the nose on this thing is all Demerara.

And this is an impression I continue to get when tasting it. The soft flavours of brown sugar, caramel, bitter chocolate, toffee, molasses and anise are forward again (they really wake up a cola-based diet soda, let me tell you, and if you add a lime wedge it kicks). It tastes a bit sweet, and it develops the additional dark fruit notes such rums tend to showcase – blackberries, ripe dark cherries, prunes, plums, with a slight acidic line of citrus or pineapple rounding things out nicely. The finish is short and faint and wispy — no gilding that lily — mostly anise, molasses and caramel, with the fruits receding quite a bit. A solid, straightforward, simple drink, I would say – no airs, no frills, very firm, and very much at home in a mix.

It’s in that simplicity, I argue, lies much of Watson’s strength and enduring appeal — “an honest and loyal rum” opined Serge Valentin of WhiskyFun in his review. It’s not terrible to drink neat, though few will ever bother to have it that way; and perhaps it’s a touch sharp and uncouth, as most such rums aged less than five years tend to be. It has those strong notes of anise and molasses and dark fruit, all good. I think, though, it’s like all the other rums mentioned above — a mixer’s fallback, a backbar staple, a bottom shelf dweller, something you drank, got a personal taste for and never abandoned entirely, something to always have in stock at home, “just in case.”

It’s in that simplicity, I argue, lies much of Watson’s strength and enduring appeal — “an honest and loyal rum” opined Serge Valentin of WhiskyFun in his review. It’s not terrible to drink neat, though few will ever bother to have it that way; and perhaps it’s a touch sharp and uncouth, as most such rums aged less than five years tend to be. It has those strong notes of anise and molasses and dark fruit, all good. I think, though, it’s like all the other rums mentioned above — a mixer’s fallback, a backbar staple, a bottom shelf dweller, something you drank, got a personal taste for and never abandoned entirely, something to always have in stock at home, “just in case.”

Such rums are are almost always and peculiarly associated with hazy, fond memories of times past, it seems to me. First jobs, first drunks, first kisses, first tastes of independence away from parents…first solo outings of the youth turning into the adult, perhaps. I may be romanticizing a drink overmuch, you could argue…but then, just read my first paragraphs again, then the last two, and ask yourself whether you don’t have at least one rum like that in your own collection. Because any rum that can make you think that way surely has a place there.

(#759)(82/100)

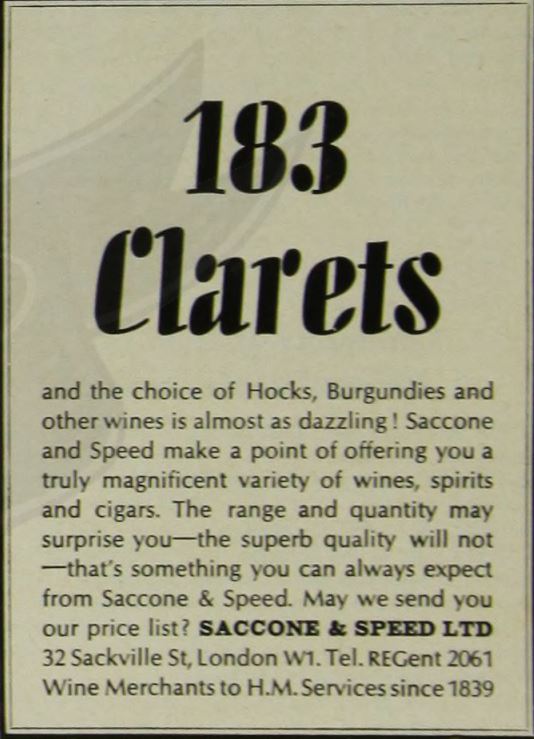

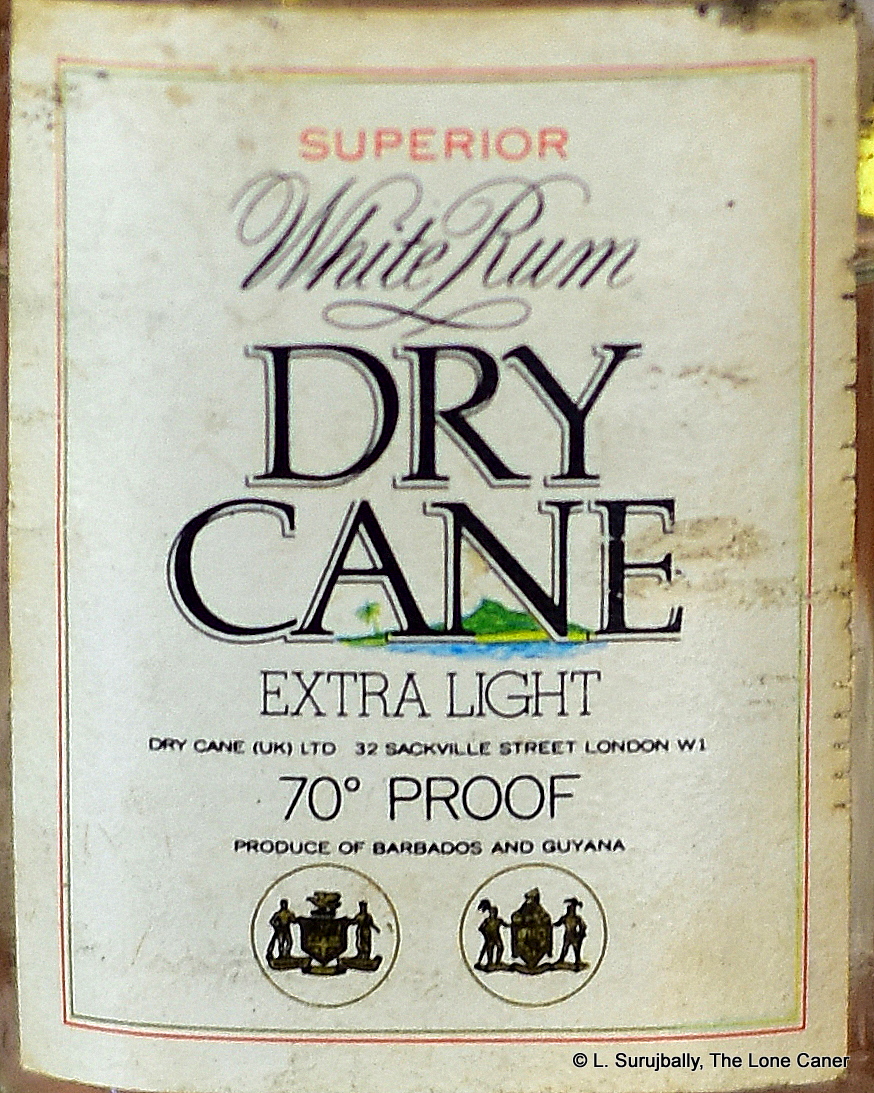

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale.

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale. Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

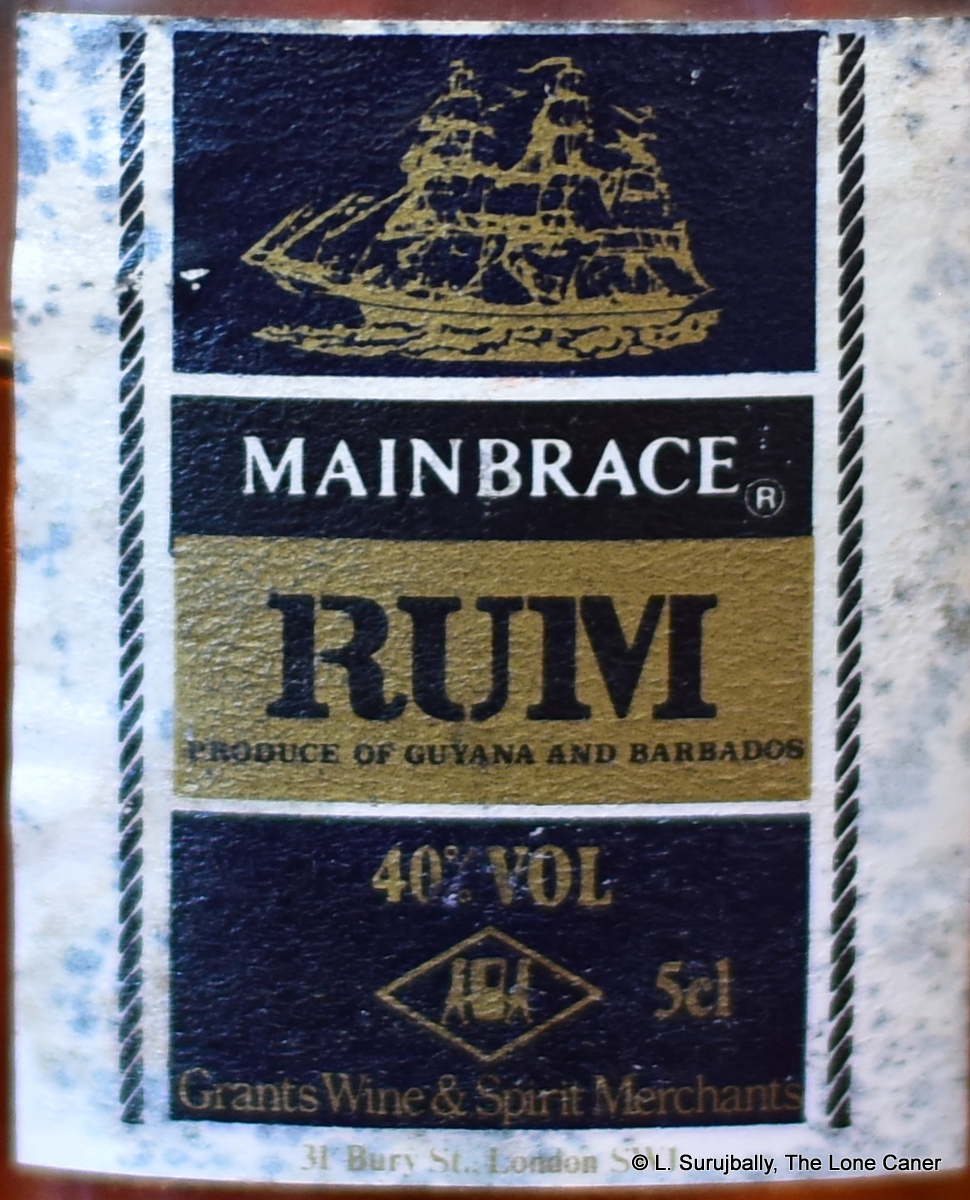

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

A well made full proof rum should be intense but not savage. The point of the elevated strength is not to hurt you, damage your insides, or give you an opportunity to prove how you rock it in the ‘Hood — but to provide crisper, clearer and stronger tastes that are more distinct (and delicious). When done right, such rums are excellent as both sippers or cocktail ingredients and therein lies much of their attraction for people across the drinking spectrum. Perhaps in the years to come, there’s the potential for rum makers to reach into the past and recreate such a remarkable profile once again. I can hope, I guess.

A well made full proof rum should be intense but not savage. The point of the elevated strength is not to hurt you, damage your insides, or give you an opportunity to prove how you rock it in the ‘Hood — but to provide crisper, clearer and stronger tastes that are more distinct (and delicious). When done right, such rums are excellent as both sippers or cocktail ingredients and therein lies much of their attraction for people across the drinking spectrum. Perhaps in the years to come, there’s the potential for rum makers to reach into the past and recreate such a remarkable profile once again. I can hope, I guess.