#290

In 2014 I looked at three very different aged cachaças from Delicana, the German maker of Brazilian rums; I had met the owner, Bert Ostermann, who has had a love affair with the country lasting many years at the Berlin Rumfest and we had a long and pleasant conversation. The central theme of his work was to age his rums in local woods, which gave them a piquant, off-base profile that at the time I didn’t care for – indeed, I scored the youngest of these rums the best, because I felt that the peculiar tastes of the wood had not had time to totally dominate the rum.

A year later I made it a point to stop by his booth again, and retasted all three which were back on display, and comparing my written notes, I find very little difference, either in the tastes, or my own opinions – the wood is just too different, and perhaps I’m not in tune enough to appreciate them the way a Brazilian might.

The current crop of cachaças, on the other hand, was something else again and I enjoyed these somewhat more – they’re still not world beaters (to me), but much more like a drink you can sip than the previous go-around. Rather than take the time to write individual essays around each one, I’ll repeat the exercise from before and provide the notes all at once. Here they are:

Castanha Artesanal Pot Still 2 Year old – pot still, aged in Castanha wood

Castanha Artesanal Pot Still 2 Year old – pot still, aged in Castanha wood

Strength 40%, colour pale orange

Nose: Very agricole like, starting off with salt and wax before becoming vegetal and grassy, dusted lightly with cinnamon and something spicier, like (no kidding) quinine.

Palate: Clean, clear, light, watery, vegetal and grassy, with some sweet corn water in there. It’s like tasting a colour, the light, sun-dappled, tropical green filtering through a jungle canopy. Hints of cinnamon, mint leaves and a slightly bitter back end, not unpleasant at all

Finish: short and sweet, more mint and vegetals, warm and unaggressive

Thoughts: If it wasn’t for the vague but distinctive wood and cinammon, I’d say this was an agricole. But of course it isn’t…it’s way too individual for that. A pretty good drink

80/100

Ipé Roxo (“rose coloured”) Artesanal pot still, aged 8 months in Ipé casks

Ipé Roxo (“rose coloured”) Artesanal pot still, aged 8 months in Ipé casks

Strength 40%, colour orange-gold

Nose: lovely intro, lemon zest, red olives, very vegetal and grassy, quite smooth

Palate: Smooth and easy, lots more red olives and tomatoes, cucumbers freshly sliced, mown grass, a few unripe white guavas….and a bit of dill. Tart on the mouth, quite nice.

Finish: Short and a little uneven, but warm and gentle for all that. More olives and brine, some soya and sweet pickles

Thoughts: Slightly better than the older Castanha (Bert is going to shake his head at me, again); I attribute that mostly to better balance in the flavours, and the lemon was really well integrated with both wood and herbals.

81/100

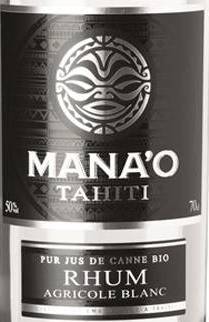

Strength 38%, white

Nose: Pow! Exploding phenols and wax and brine, petrol and hot asphalt. Was this really just 38%? Amazingly potent stuff, this, erratic and untamed, almost wild….it reminded me of the Haitian clairins, actually, and I mean that in a good way

Palate: Like the Jamel, it did a one-eighty degree turn. Thin and watery cucumbers in brine, vague vanillins, white sugar dissolved in extremely diluted lemon juice, a tad oily in mouthfeel, some sweet baking spices in there, cinnamon and nutmeg, too light to really be noticeable, but all serve to tame the nose.

Finish: Gone in a flash, hardly anything except crushed grass and a faint banana whiff

Thoughts: Should be stronger to make the point the nose advertised

77/100

Final comments

None of these rums is new, and two have won prizes, so it’s not as if Bert spent the last year refining his output, tweaking his ageing regimen and changing his barrels in any way. But these are all younger than the ones I tried back in 2014 and I liked them more – they were lighter and cleaner in some way, integrated their tastes better, and the influence of the woods was held in check in a way that allowed more diffident flavours to come through. I wonder if that will turn out to be a characteristic of the type, that the ones under five years old will be the better ones. The journey continues.

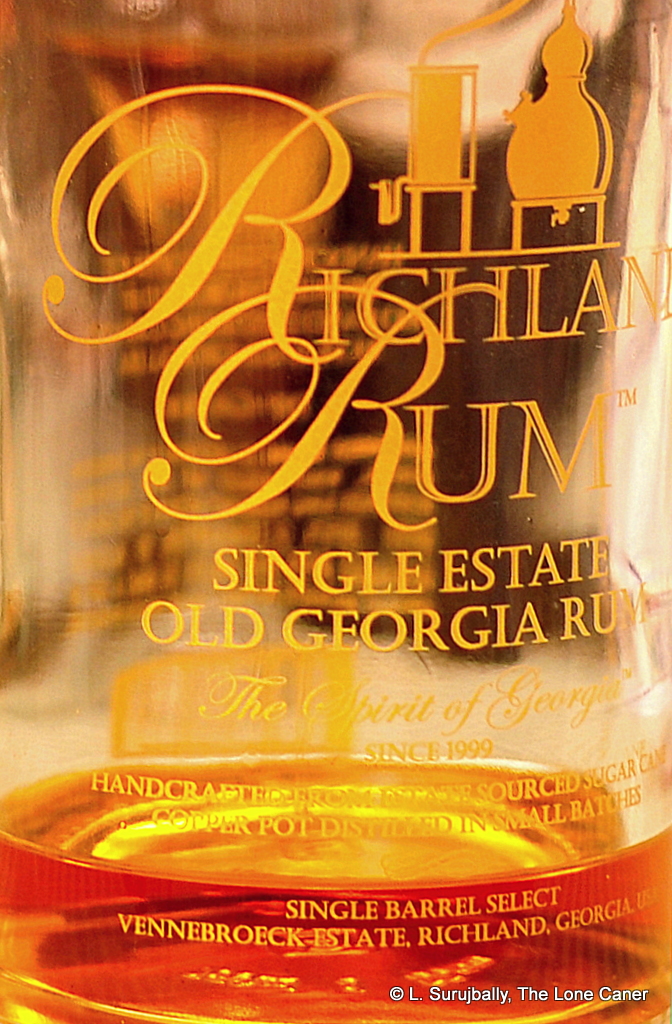

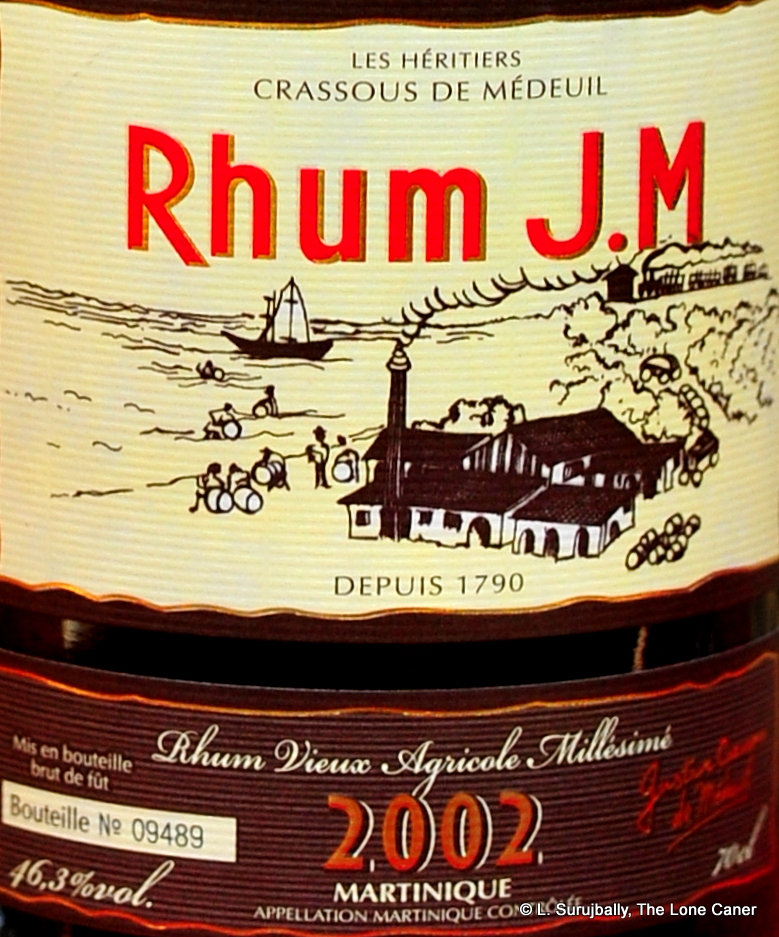

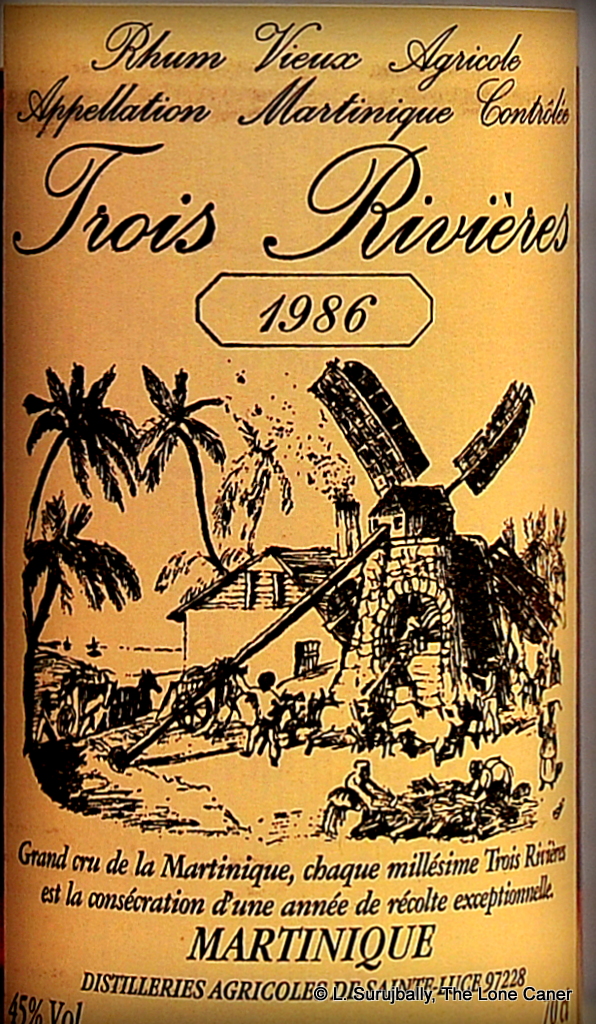

This dark orange-gold ten year old began well on the nose: phenols, acetone, caramel, sweet red licorice, wet cardboard, it gave a good impression of some pot still action going on here, even though it was a column still product. Then there was some fanta or coke — some kind of soda pop at any rate, which I thought odd. Then cherries and citrus zest notes, blooming slowly into black olives, coffee, nuttiness and light vanilla. As a whole, the experience was somewhat easy due to its softness, but overall it was too well constructed for me to dismiss it out of hand as thin or weak.

This dark orange-gold ten year old began well on the nose: phenols, acetone, caramel, sweet red licorice, wet cardboard, it gave a good impression of some pot still action going on here, even though it was a column still product. Then there was some fanta or coke — some kind of soda pop at any rate, which I thought odd. Then cherries and citrus zest notes, blooming slowly into black olives, coffee, nuttiness and light vanilla. As a whole, the experience was somewhat easy due to its softness, but overall it was too well constructed for me to dismiss it out of hand as thin or weak.

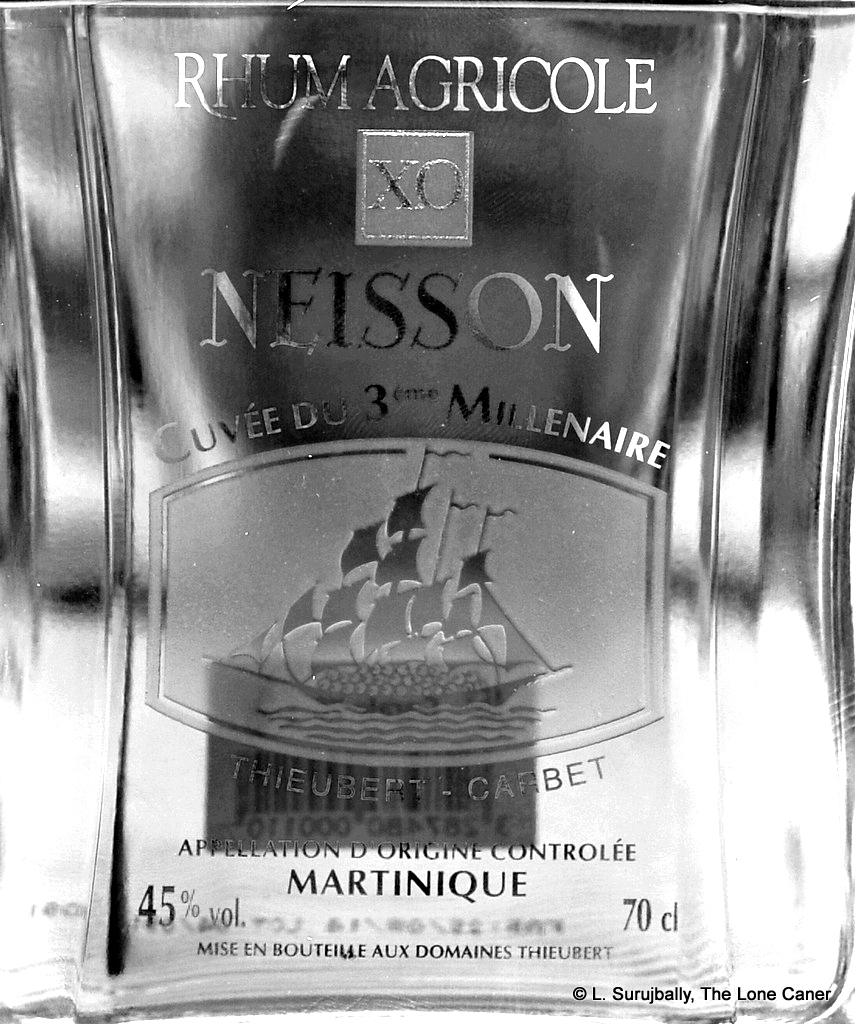

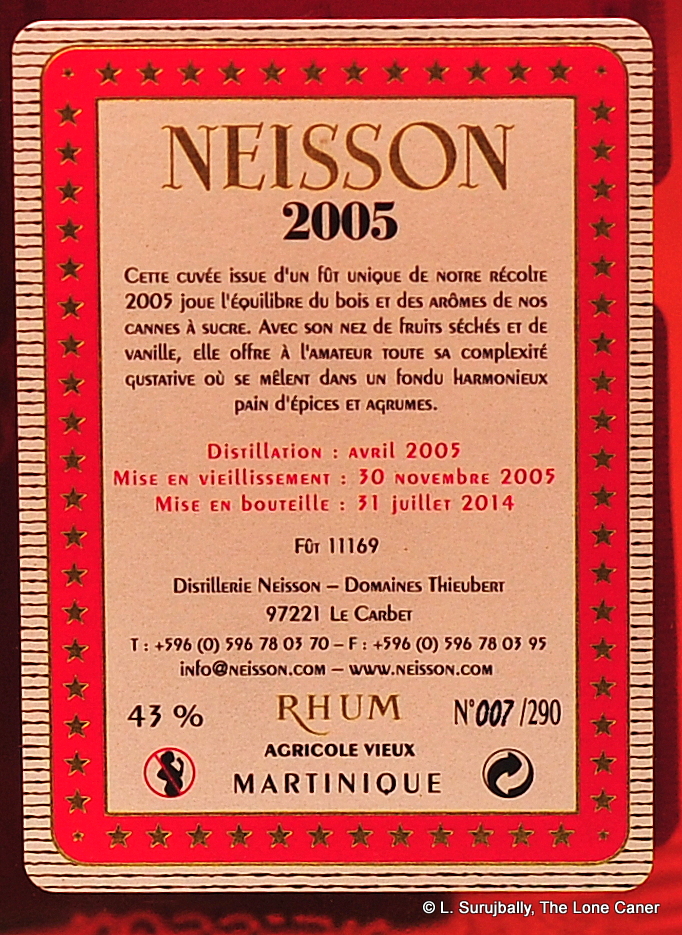

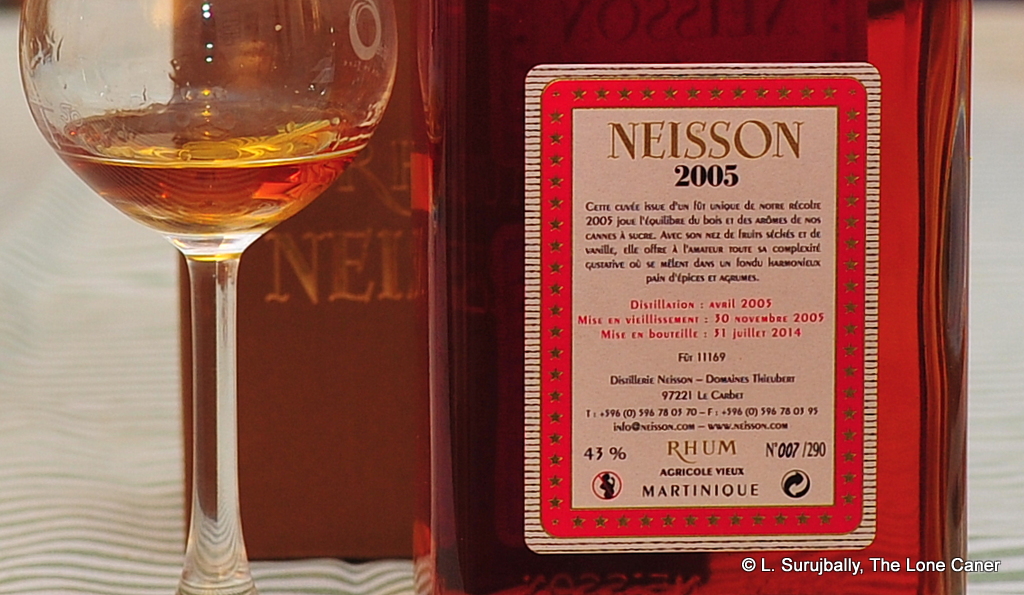

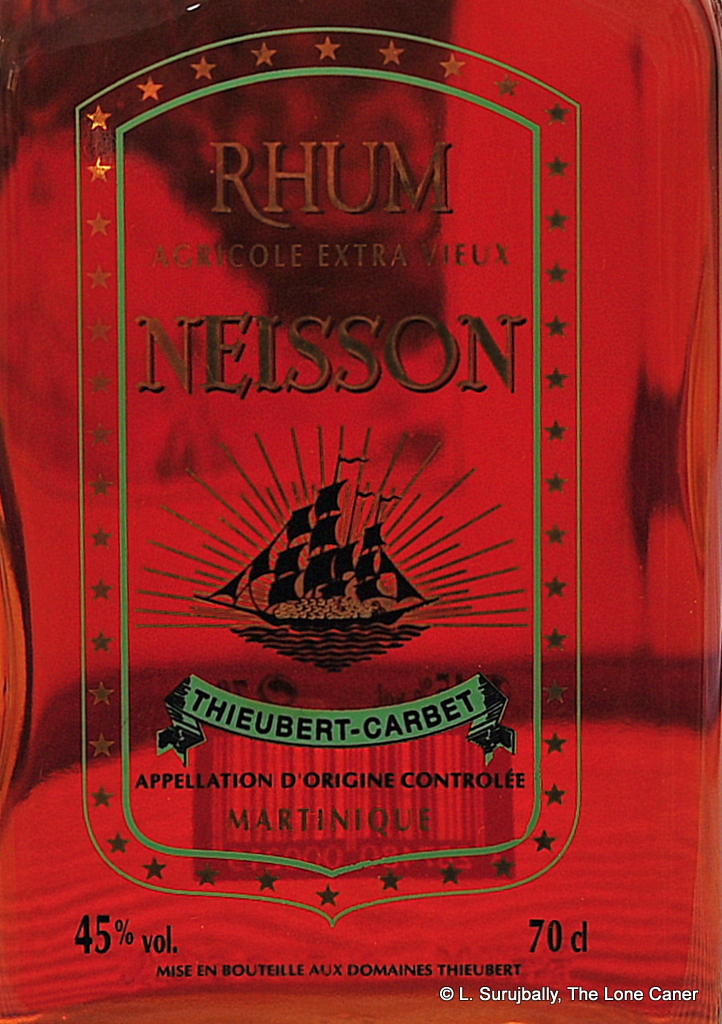

I speak of course of that oily, sweet salt tequila note that I’ve noted on all Neissons so far. What made this one a standout in its own way was the manner in which that portion of the profile was dialled down and restrained on the nose – the 43% made it an easy sniff, rich and warm, redolent of apples, pears,and watermelons…and that was just the beginning. As the rhum opened up, the fleshier fruits came forward (apricots, ripe red cherries, pears, papayas, rosemary, fennel, attar of roses) and I noted with some surprise the way more traditional herbal and grassy sugar cane sap notes really took a backseat – it didn’t make it a bad rhum in any way, just a different one, somewhat at right angles to what one might have expected.

I speak of course of that oily, sweet salt tequila note that I’ve noted on all Neissons so far. What made this one a standout in its own way was the manner in which that portion of the profile was dialled down and restrained on the nose – the 43% made it an easy sniff, rich and warm, redolent of apples, pears,and watermelons…and that was just the beginning. As the rhum opened up, the fleshier fruits came forward (apricots, ripe red cherries, pears, papayas, rosemary, fennel, attar of roses) and I noted with some surprise the way more traditional herbal and grassy sugar cane sap notes really took a backseat – it didn’t make it a bad rhum in any way, just a different one, somewhat at right angles to what one might have expected. But I also didn’t get much in the way of wonder, of amazement, of excitement…something that would enthuse me so much that I couldn’t wait to write this and share my discovery. That doesn’t make it a bad rhum at all (as stated, I thought it was damned good on its own merits, and my score reflects that)…on the other hand, it hardly makes you drop the wife off to her favourite sale and rush out to the nearest shop, now, does it?

But I also didn’t get much in the way of wonder, of amazement, of excitement…something that would enthuse me so much that I couldn’t wait to write this and share my discovery. That doesn’t make it a bad rhum at all (as stated, I thought it was damned good on its own merits, and my score reflects that)…on the other hand, it hardly makes you drop the wife off to her favourite sale and rush out to the nearest shop, now, does it?

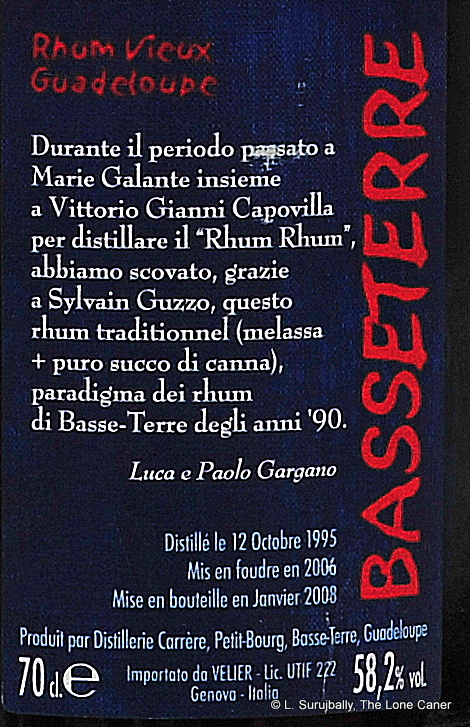

This amazing mix of class and sleaze and style continued without missing a beat when I tasted it. Sure, 59.8% was something of a hammer to the glottis but man, it was so well assembled that it actually felt softer than it really was: I tried the Liberation on and off over four days, and every time I added more stuff to my tasting notes, becoming more impressed each time. The dark gold rhum started the party rolling with plums, peaches and unripe apricots, which provided a firm bedrock that flawlessly supported sharper tangerines and passion fruit and pomegranates. As it opened up (and with water), further notes of vanilla and mild salted caramel came to the fore, held together by breakfast spices and a very good heat that was almost, but not quite, sharp – one could barely tell how strong the drink truly was, because it ran across the tongue so well.

This amazing mix of class and sleaze and style continued without missing a beat when I tasted it. Sure, 59.8% was something of a hammer to the glottis but man, it was so well assembled that it actually felt softer than it really was: I tried the Liberation on and off over four days, and every time I added more stuff to my tasting notes, becoming more impressed each time. The dark gold rhum started the party rolling with plums, peaches and unripe apricots, which provided a firm bedrock that flawlessly supported sharper tangerines and passion fruit and pomegranates. As it opened up (and with water), further notes of vanilla and mild salted caramel came to the fore, held together by breakfast spices and a very good heat that was almost, but not quite, sharp – one could barely tell how strong the drink truly was, because it ran across the tongue so well.

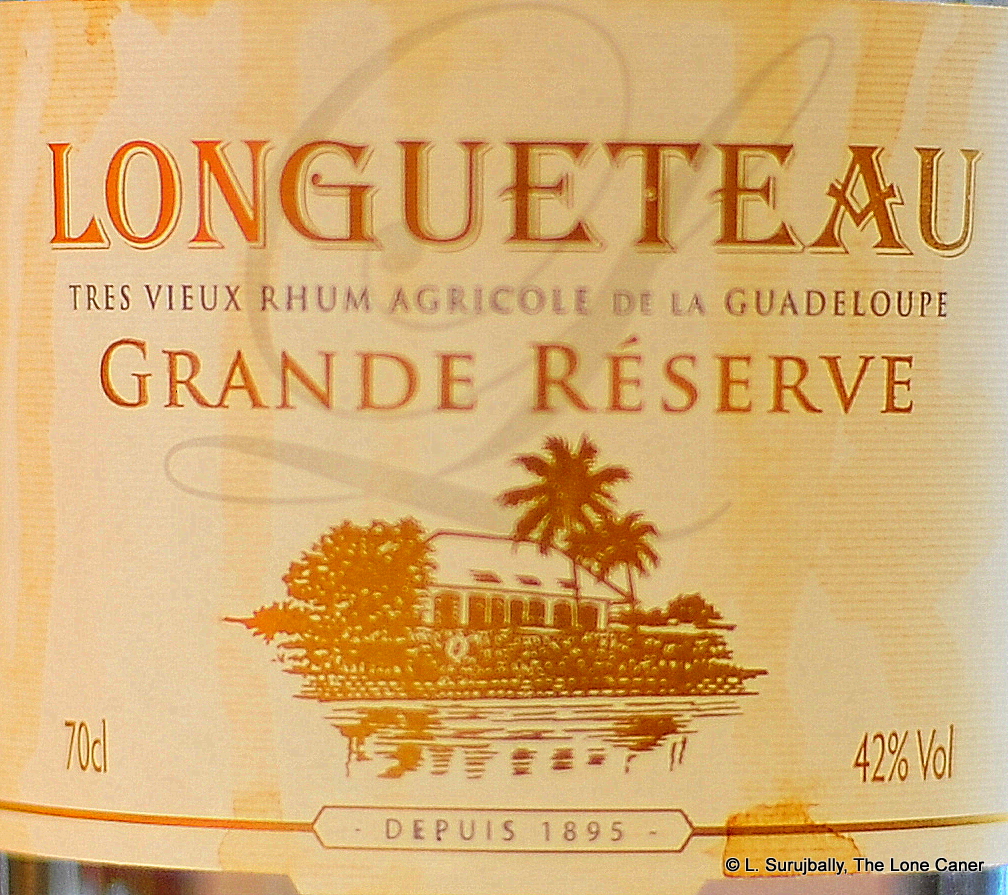

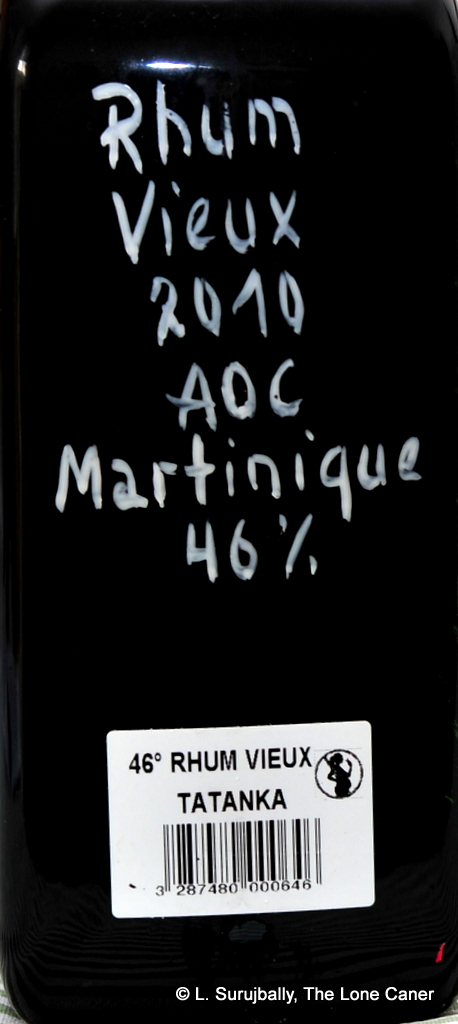

Okay, I jest a little, but consider the nose on the 46% orange-gold spirit. It displayed that same spicy, musky and almost meaty scent of salt butter and olives and tequila doing some bodacious ragtime, sweat and stale eau-de-vie going off in all directions. It was thick and warm to smell, mellowing out into more fleshy, overripe (almost going bad) mangoes and papayas and pineapples, just not so sweet. Spices, maybe cardamom, and some wet coffee grounds. At the back end, after a while, it was possible to detect the leather and smoke and slight bitter whisper of some wood tannins hinting at some unspecified ageing, but where was the crisp, clear aroma of an agricole? The grasses and herbaceous lightness that so characterizes the style? I honestly couldn’t smell it clearly, could barely sense it – so, points for originality, not so much for recognition (though admittedly, that was just me, and your own mileage may vary;

Okay, I jest a little, but consider the nose on the 46% orange-gold spirit. It displayed that same spicy, musky and almost meaty scent of salt butter and olives and tequila doing some bodacious ragtime, sweat and stale eau-de-vie going off in all directions. It was thick and warm to smell, mellowing out into more fleshy, overripe (almost going bad) mangoes and papayas and pineapples, just not so sweet. Spices, maybe cardamom, and some wet coffee grounds. At the back end, after a while, it was possible to detect the leather and smoke and slight bitter whisper of some wood tannins hinting at some unspecified ageing, but where was the crisp, clear aroma of an agricole? The grasses and herbaceous lightness that so characterizes the style? I honestly couldn’t smell it clearly, could barely sense it – so, points for originality, not so much for recognition (though admittedly, that was just me, and your own mileage may vary;  Still, there was little to find fault with once I actually got around to tasting the medium-going-on-heavy rhum. Once one got past the briny, slightly bitter initial profile, things warmed up, and it got interesting in a hurry. Green olives, peppers, some spice and bite, sure, but there was softer stuff coiling underneath too: peaches, apricots, overripe cherries (on the verge of going bad); salt beef and butter again (the concomitant creaminess was quite appealing), and I dunno, a chutney of some kind, stuffed with dill and sage. Like I said, really interesting – it was quite a unique taste profile. And the finish followed along from there – soft and warm and lasting, with sweet and salt and dusty hay mixing well – I am not reaching when I say it reminded me of the mingled dusty scents of a small cornershop in Guyana, where jars of sweets and medicines and noodles and dried veggies were on open display, and my brother and I would go to buy nibbles and maybe try to sneak into the pool hall next door.

Still, there was little to find fault with once I actually got around to tasting the medium-going-on-heavy rhum. Once one got past the briny, slightly bitter initial profile, things warmed up, and it got interesting in a hurry. Green olives, peppers, some spice and bite, sure, but there was softer stuff coiling underneath too: peaches, apricots, overripe cherries (on the verge of going bad); salt beef and butter again (the concomitant creaminess was quite appealing), and I dunno, a chutney of some kind, stuffed with dill and sage. Like I said, really interesting – it was quite a unique taste profile. And the finish followed along from there – soft and warm and lasting, with sweet and salt and dusty hay mixing well – I am not reaching when I say it reminded me of the mingled dusty scents of a small cornershop in Guyana, where jars of sweets and medicines and noodles and dried veggies were on open display, and my brother and I would go to buy nibbles and maybe try to sneak into the pool hall next door. Rumaniacs Review 018 | 0418

Rumaniacs Review 018 | 0418

The question I asked of the 1975 (which I was using as a control alongside the Rhum Rhum Liberation Integrale, the

The question I asked of the 1975 (which I was using as a control alongside the Rhum Rhum Liberation Integrale, the

out ever letting you forget they existed. Salt beef in brine, red olives, grass, tannins, wood and faint smoke were more readily discernible, mixed in with heavier herbs like fennel and rosemary. These well balanced aromas were tied together by duskier notes of burnt sugar and vanillas and as it stood and opened up, slow scents of cream cheese and marshmallows crept out to satisfy the child within.

out ever letting you forget they existed. Salt beef in brine, red olives, grass, tannins, wood and faint smoke were more readily discernible, mixed in with heavier herbs like fennel and rosemary. These well balanced aromas were tied together by duskier notes of burnt sugar and vanillas and as it stood and opened up, slow scents of cream cheese and marshmallows crept out to satisfy the child within.