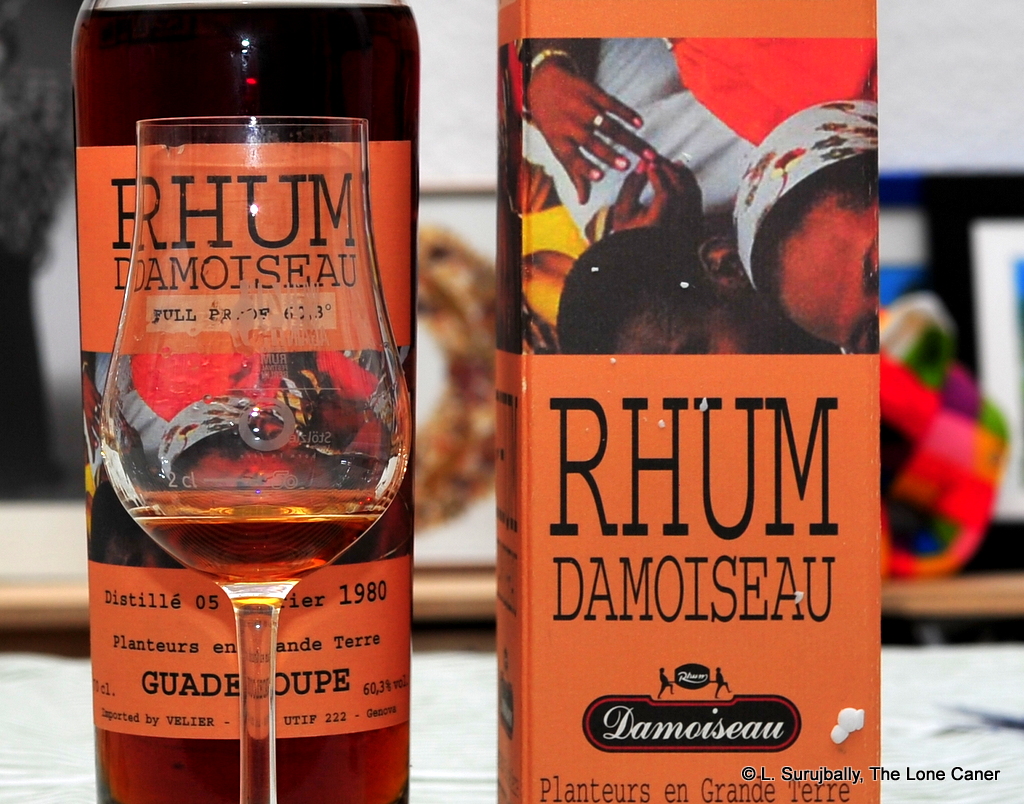

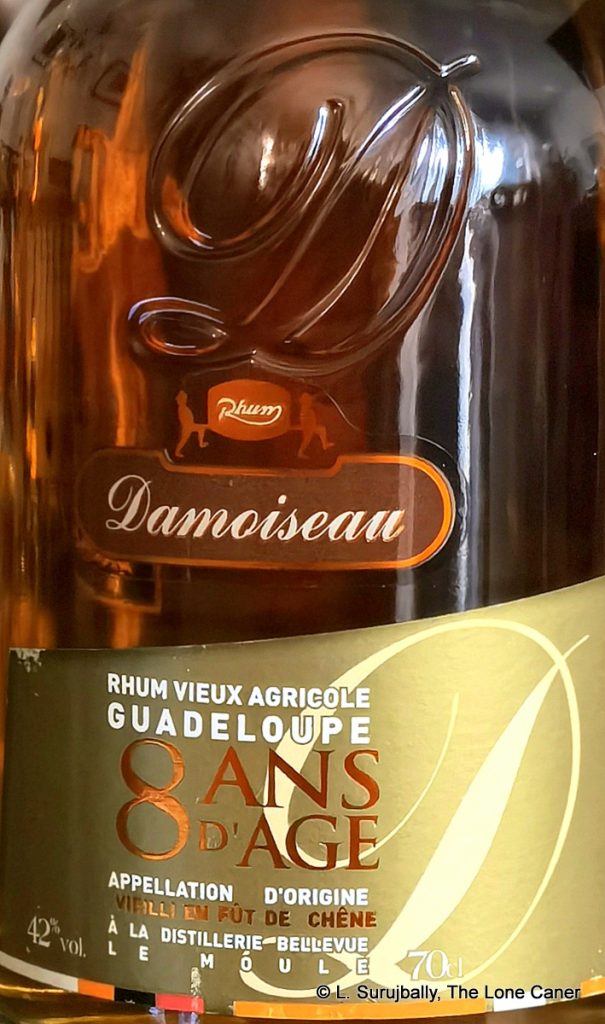

After more than a decade of writing about rhum agricole, its not entirely surprising that I’ve written more about Martinique rhums than Guadeloupe’s or Reunion’s or Madeira’s…yet more about Damoiseau’s products than any other distillery on any of these islands. There’s just something about the subtly sumptuous roundness of their rhums that appeals to me, which is an observation I’ve made about Guadeloupe rhums as a whole before. Martinique rhums may be more elegant, more artistic, more precisely dialled in…but Guadeloupe’s rhums are often a whole lot more fun.

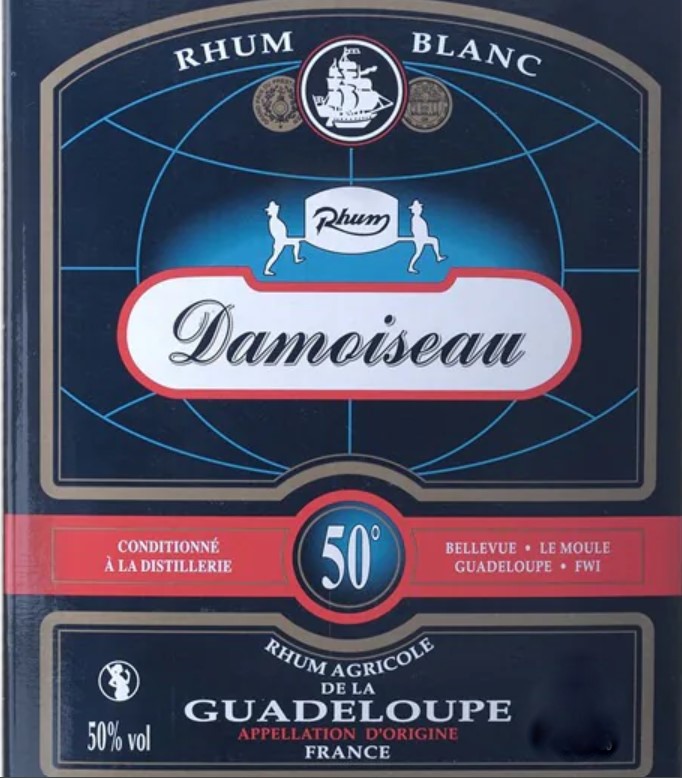

Therefore my statistical appreciation for Damoiseau makes it peculiar that I’ve never actually written anything about one of their solid, down to earth island staples – the 50º rhum agricole blanc, in this case, which is one of their regular line of bartenders’ rhums that also comes in variations of 40º and 55º (the numbers represent the ABV). And oddly, I’ve been keeping a weather eye out for it, ever since Josh Miller did his personal agricole challenge back in 2016 and the 55º came out on top.

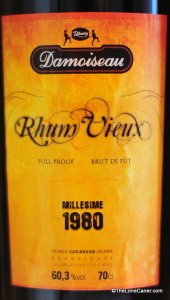

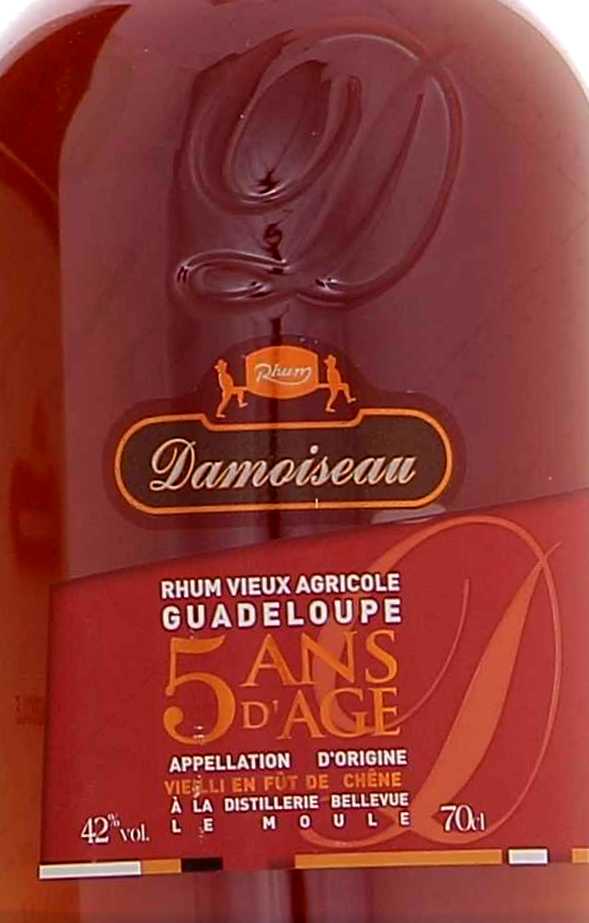

Today we’ll get to that, and to begin with, let’s run down the stats. It is a cane juice rhum (of course), immediately set to ferment after crushing for a day or two (24-36 hours is the usual time), before being run through a traditional column still to emerge frothing, hissing, spitting and snarling at around 88% ABV (this is what Damoiseau’s own site says, and although there are other sources that say 72%, you can guess which one I’m going with). Here’s where it gets interesting: the rhum is in fact aged a bit – except they don’t call it that. They say it’s “rested” – by which they mean the distillate is dunked into massive wooden foudres of perhaps 30,000-litre capacity and left to chill out and settle down and maybe play some dominos while being regularly aerated by constant stirring and agitation. Then after it’s considered to be ready — which can be anywhere from three to six months — it’s drawn off, diluted to the appropriate strength, and bottled. It’s unclear whether any filtration takes place to remove colour but somehow I doubt it – there’s a pale yellow tinge to it that hints at the wood influence, however minimal.

Today we’ll get to that, and to begin with, let’s run down the stats. It is a cane juice rhum (of course), immediately set to ferment after crushing for a day or two (24-36 hours is the usual time), before being run through a traditional column still to emerge frothing, hissing, spitting and snarling at around 88% ABV (this is what Damoiseau’s own site says, and although there are other sources that say 72%, you can guess which one I’m going with). Here’s where it gets interesting: the rhum is in fact aged a bit – except they don’t call it that. They say it’s “rested” – by which they mean the distillate is dunked into massive wooden foudres of perhaps 30,000-litre capacity and left to chill out and settle down and maybe play some dominos while being regularly aerated by constant stirring and agitation. Then after it’s considered to be ready — which can be anywhere from three to six months — it’s drawn off, diluted to the appropriate strength, and bottled. It’s unclear whether any filtration takes place to remove colour but somehow I doubt it – there’s a pale yellow tinge to it that hints at the wood influence, however minimal.

Anyway, what does it sample like? In a word – lekker. It reminds me of all the reasons I like unaged white rhums and why I never tire of sampling agricoles. It smells of gherkins and light red peppers in sweet vinegar; brine and olives and sweet sugar water. Then of course there are pears, cooking herbs (parsley and sage and mint), green grasses, watermelon, and papaya and it’s just a delight to inhale this stuff.

While the stated purpose of such white rhums is to make a ti’punch — at which I’m sure this does a bang up job — for consistency’s sake I have to try ‘em neat and here too, there’s nothing bad to say…the heated pungency of the rhum is amazing (I can only imagine what the 55º is like). It is unapologetically rough when initially sipped without warning, then calms down quickly and ends up simply being strong and unyielding and flavourful beyond expectations. There is the obligatory note of sugar cane sap, the sense of new mown grass on a hot and sunny day with the sprinkler water drying on hot concrete alongside. There are the watery fruit the nosed promised – pears, white guavas, papayas; some delicate citrus notes (lime zest and cumin); a touch of basil and mint; and overall a smooth and almost-hot potency that slides on the palate without savagery or bite, just firmness and authority. And the finish is exactly like that – a bit shortish, sweet, minerally, and herbal with sugar cane sap, light fruits…the very model of a modern major agricole.

This is a blanc rhum that still surprised with its overall quality. For one thing, it was more civilised than other such rhums I recall (and I remember the Sajous), and there were subtle notes coiling through the experience that suggested the foudres in which it rested had a bit more to offer than just sage advice. For another it’s quite clean goes down rather more easily than one might expect and while never straying too far from its cane juice roots, still manages to provide a somewhat distinct, occasionally unusual experience.

So, rested or aged, oak or steel, unaged or not quite…it doesn’t really matter – my contention is simply that any time in a reactive environment, however short, does change the base distillate, if only a little. That’s merely an observation, mind, not a criticism; in any case, the taste profile does support the thesis — because the 50 is subtly drier, richer and more complex than some completely fresh unaged still strength cane juice popskull that I’ve had in years past. It tastes pretty damned fine, and at the end, it comes together with a sort of almost-refined rhythm that shouldn’t work, but yet does, and somehow manages to salvage some elegance from all that rough stuff and provides a tasting experience to savour.

(#989)(85/100) ⭐⭐⭐½

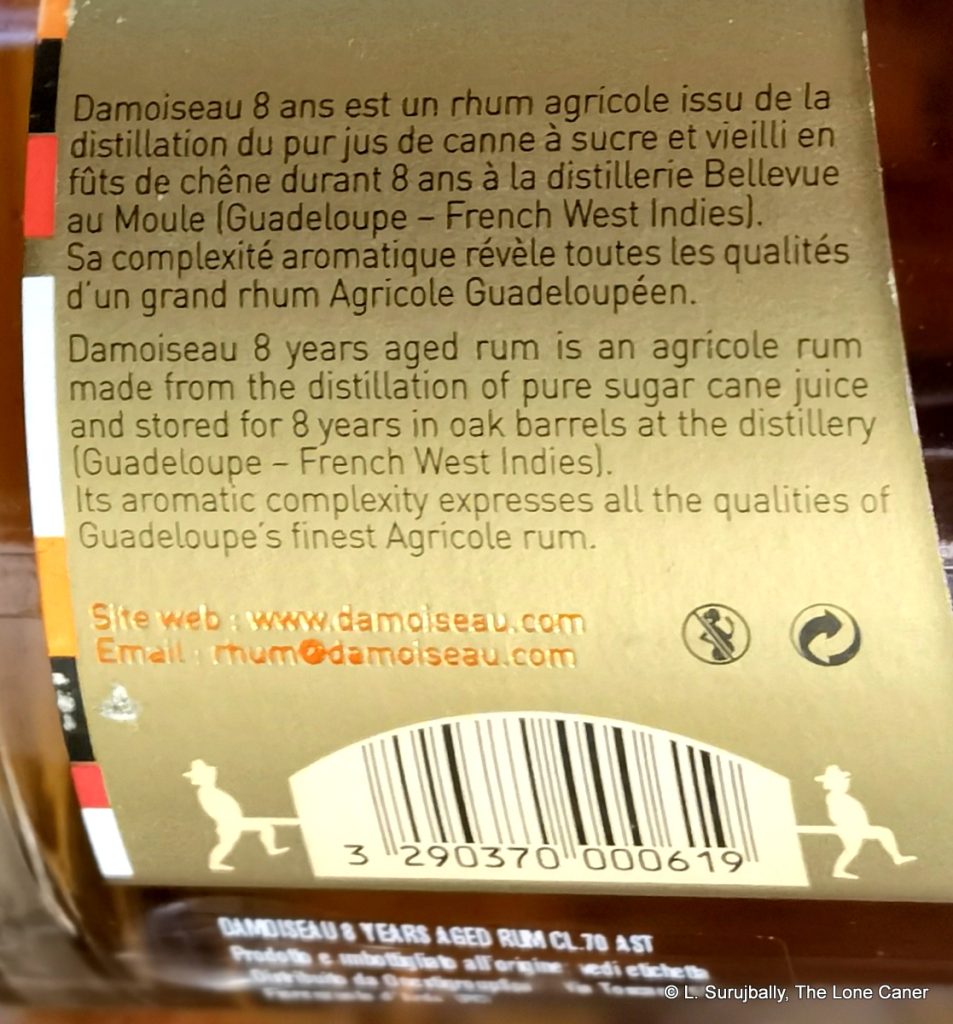

The nose doesn’t help narrow down the origin (though I have my suspicions), and the palate doesn’t either – but it

The nose doesn’t help narrow down the origin (though I have my suspicions), and the palate doesn’t either – but it

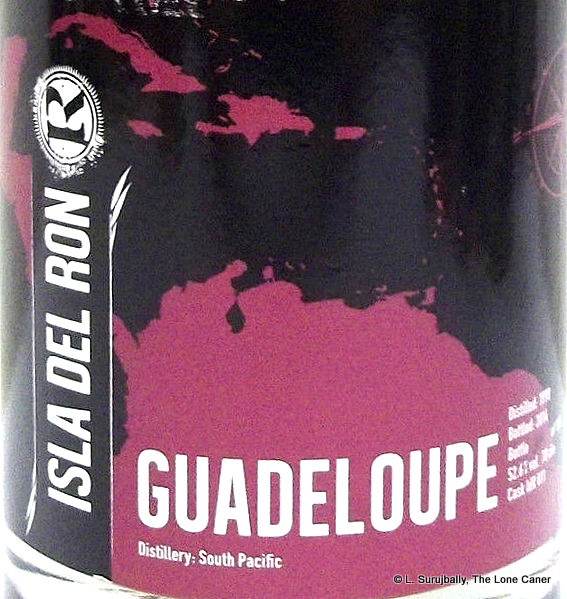

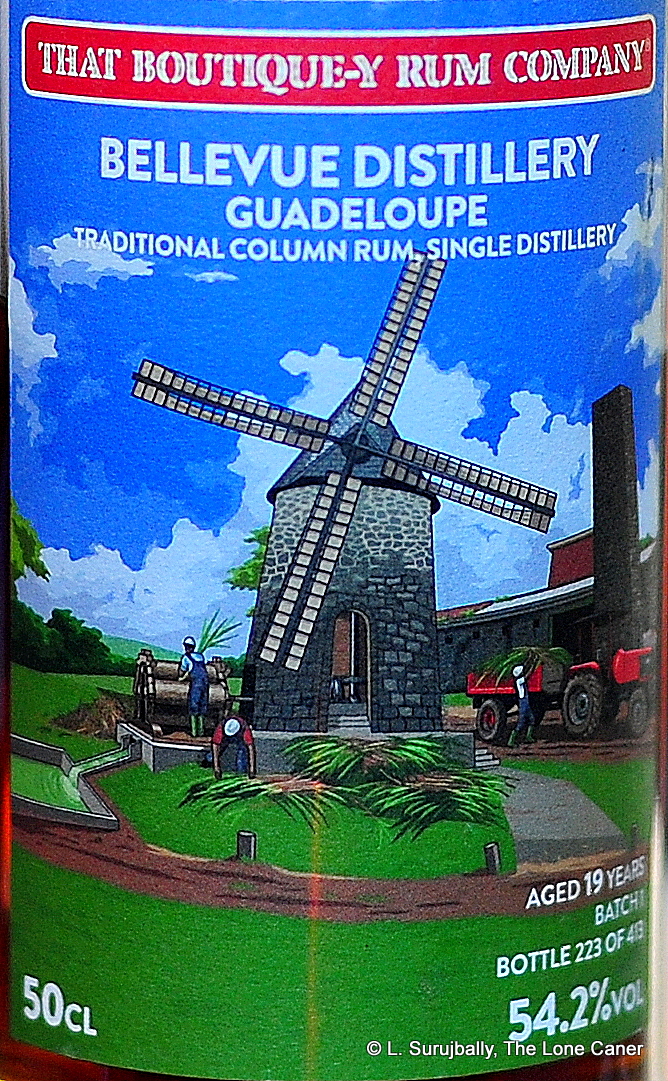

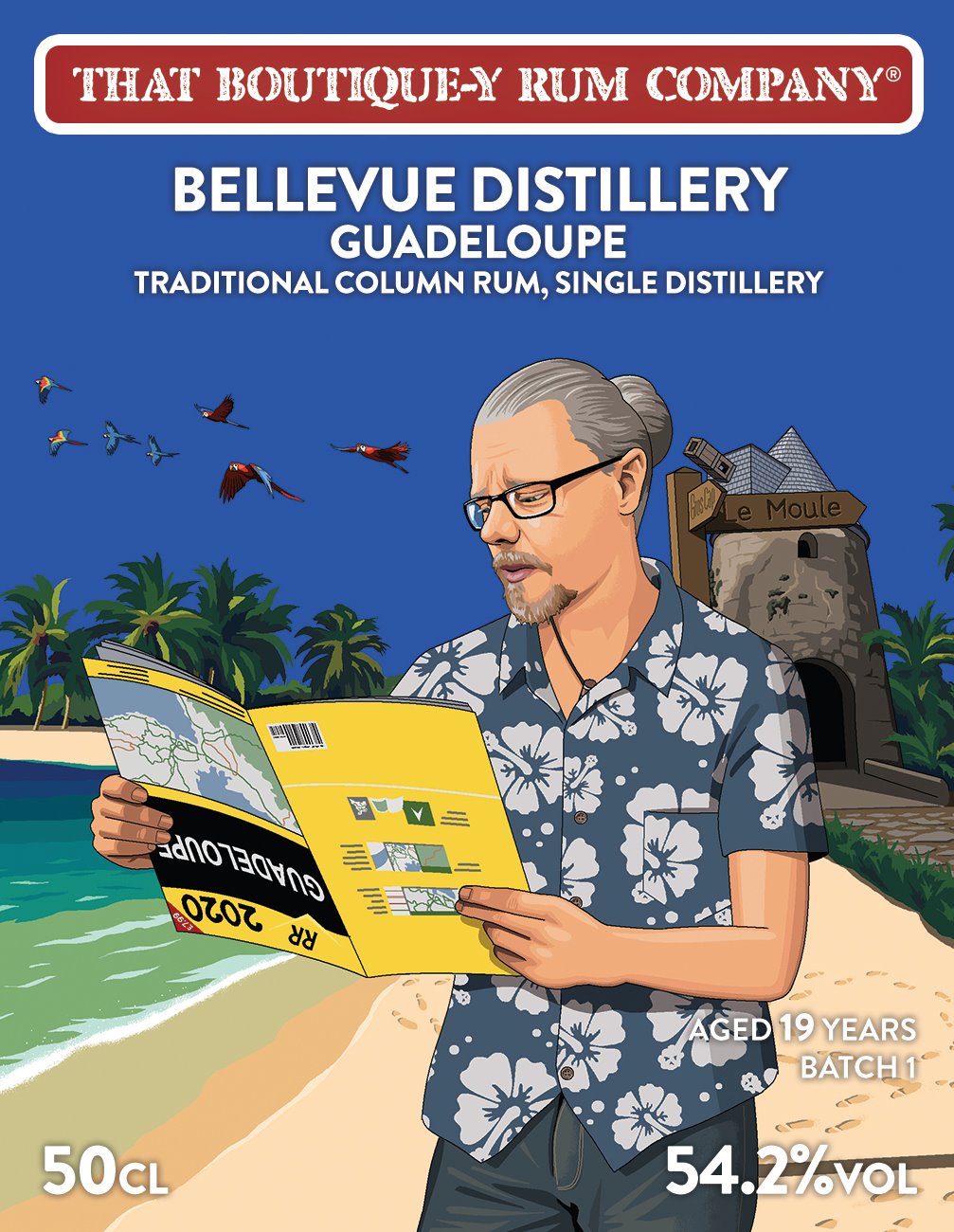

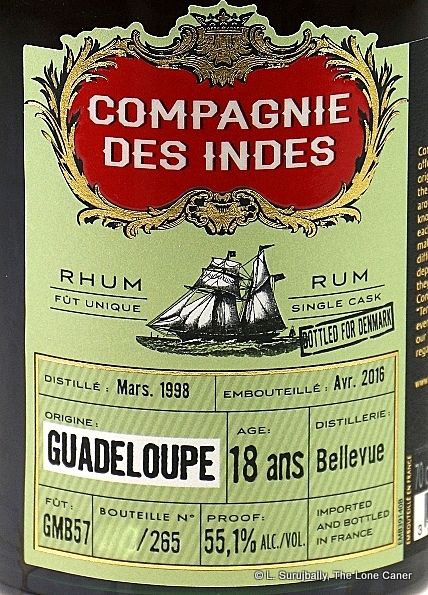

Take this one, which proves that TBRC has a knack for ferreting out good barrels. It’s not often you find a rum that is from the French West Indies aged beyond ten years — Neisson’s been making a splash recently with its 18 YO, you might recall, for that precise reason. To find one that’s a year older from Guadeloupe in the same year is quite a prize and I’ll just mention it’s 54.2%, aged seven years in Guadeloupe and a further twelve in the UK, and outturn is 413 bottles. On stats alone it’s the sort of thing that makes my glass twitch.

Take this one, which proves that TBRC has a knack for ferreting out good barrels. It’s not often you find a rum that is from the French West Indies aged beyond ten years — Neisson’s been making a splash recently with its 18 YO, you might recall, for that precise reason. To find one that’s a year older from Guadeloupe in the same year is quite a prize and I’ll just mention it’s 54.2%, aged seven years in Guadeloupe and a further twelve in the UK, and outturn is 413 bottles. On stats alone it’s the sort of thing that makes my glass twitch. Guadeloupe rums in general lack something of the fierce and stern AOC specificity that so distinguishes Martinique, but they’re close in quality in their own way, they’re always good, and frankly, there’s something about the relative voluptuousness of a Guadeloupe rhum that I’ve always liked. Peter sold me on the quality of the

Guadeloupe rums in general lack something of the fierce and stern AOC specificity that so distinguishes Martinique, but they’re close in quality in their own way, they’re always good, and frankly, there’s something about the relative voluptuousness of a Guadeloupe rhum that I’ve always liked. Peter sold me on the quality of the

grassy elements in the background, serving to swell a note or two without ever dominating the symphony

grassy elements in the background, serving to swell a note or two without ever dominating the symphony