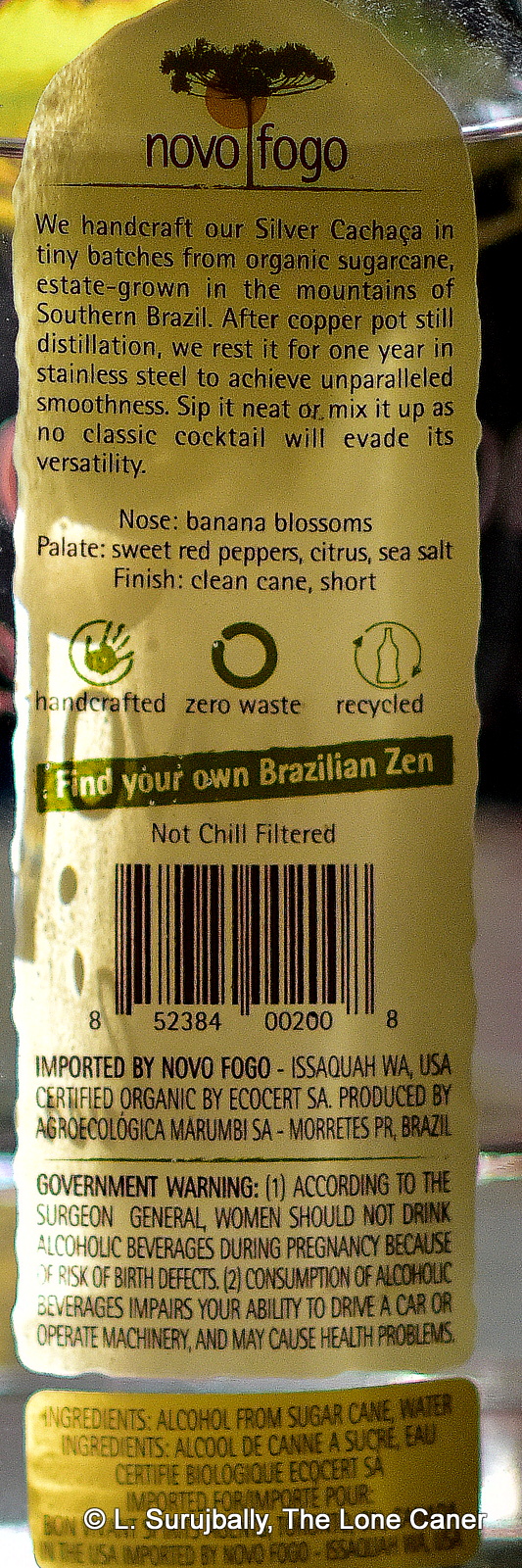

No, that’s not another typo in the title, it’s just the way the bottle spelled “rum” so I followed along even if it is an agricole-style product and by convention it might have been better termed “rhum” (though the words mean the same thing – it’s purely a matter of perception). Since looking at the Engenho Novo aged rum last time, I thought it would be fitting to stick with the island of Madeira and see what one of their whites would be like, especially since I had been so impressed with the RN Jamaican Pot Still 57% some years ago….would this one live up to to the rep the Caribbean one garnered for itself?

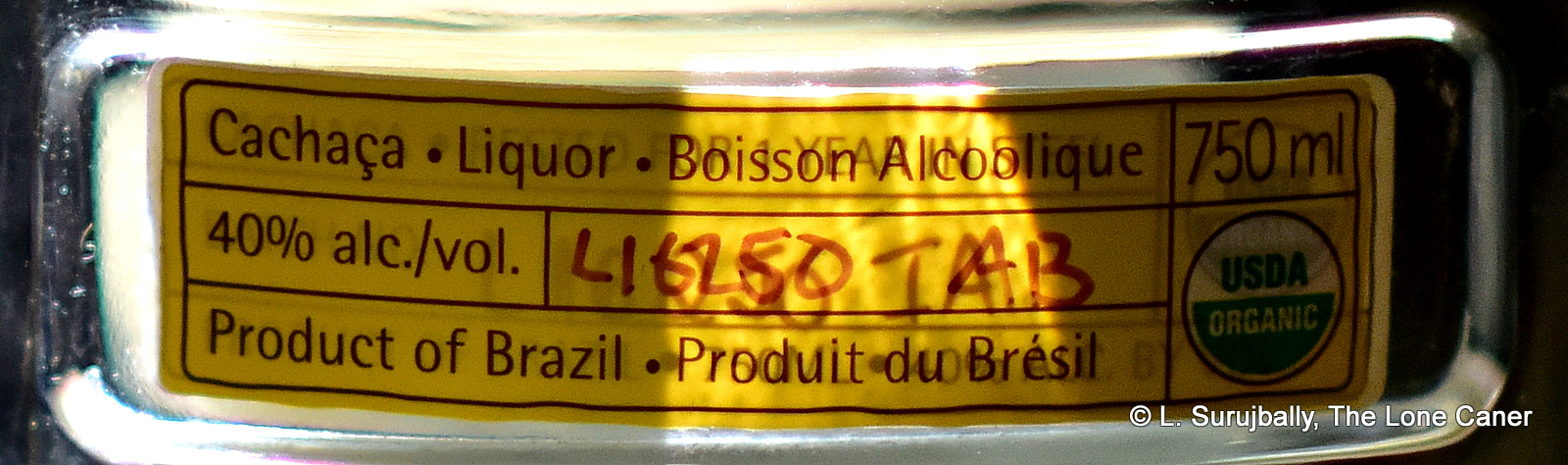

Curiously, there isn’t much to go on as regards the background aside from the obvious: we know it is 50% ABV and made from cane juice in a column column still…but it come not from Engenho Novo (which is to say, the reconstituted William Hinton, and the source of the rum for Rum Nation’s Rares), but from Engenhos do Norte in Porto da Cruz – Fabio remarked in an email tome that he liked it better for this purpose than the Novo). It’s unclear whether it’s unaged and unfiltered, or lightly aged and then filtered to clarity…and if the latter case is what happened, then what kind of casks. We’re not sure what the “Limited edition” on the label actually means. And, as always with RN, there’s also the question of any additions. We can however infer that based on the chubby, stubby bottle and label style, that the rum is part of their standard lineup and not the higher-proofed, higher-quality, higher-priced Rares (as an aside, I hope they never lose the old postage stamps incorporated into the design), and possibly from the word “crystal” used in their website materials, that it has been filtered. But I’ll amend the post if I hear back from them.

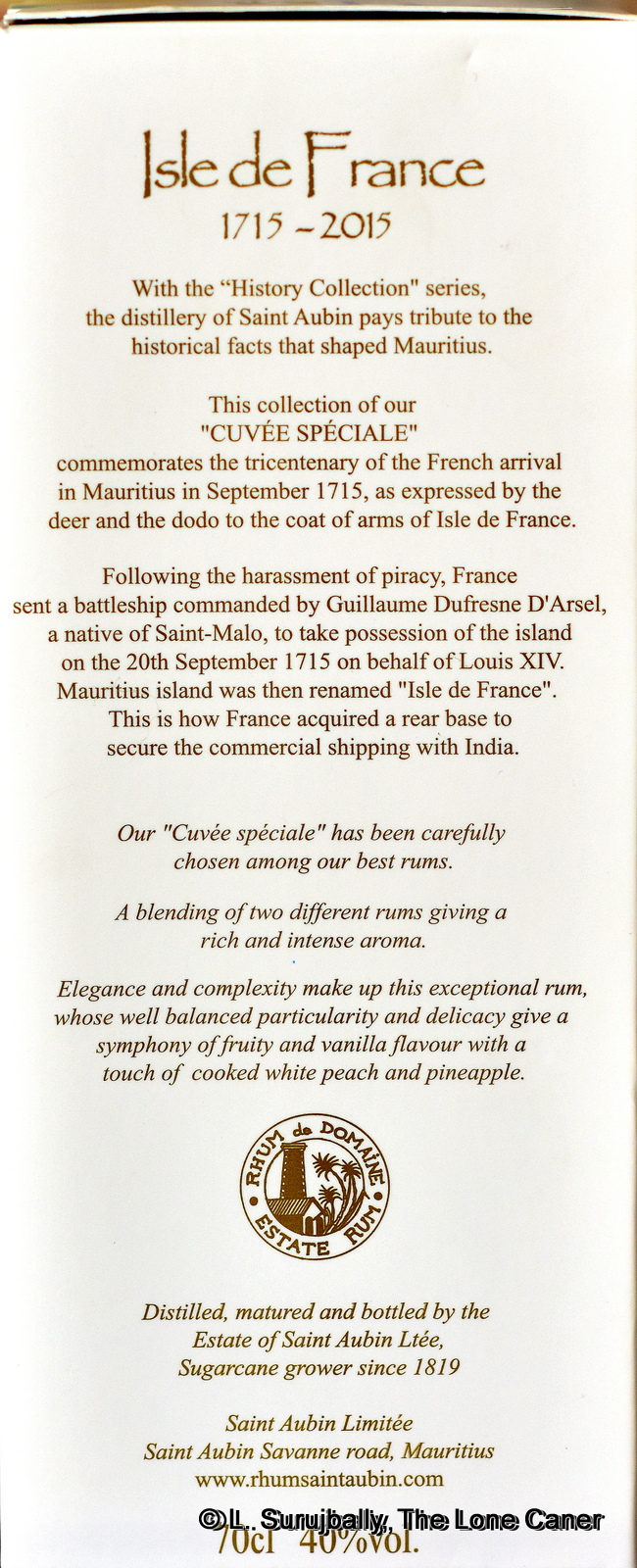

Anyway, here’s what it was like. The nose of the Ilha da Madeira fell somewhere in the middle of the line separating a bored “meh” from a more disbelieving “holy-crap!”. It was a light melange of a playful sprite-like aroma mixed in with more serious brine and olives, a little sweet, and delicate – flowers, sugar water, grass, pears, guavas, mint, some marzipan. You could sense something darker underneath – cigarette tar, acetones – but these never came forward, and were content to be hinted at, not driven home with a sledge. Not really a brother to that fierce Jamaican brawler, more like a cousin, a closer relative to the Mauritius St. Aubin blanc (for example). What it lacked in pungency it made up for in both subtlety and harmony, even at 50%.

Anyway, here’s what it was like. The nose of the Ilha da Madeira fell somewhere in the middle of the line separating a bored “meh” from a more disbelieving “holy-crap!”. It was a light melange of a playful sprite-like aroma mixed in with more serious brine and olives, a little sweet, and delicate – flowers, sugar water, grass, pears, guavas, mint, some marzipan. You could sense something darker underneath – cigarette tar, acetones – but these never came forward, and were content to be hinted at, not driven home with a sledge. Not really a brother to that fierce Jamaican brawler, more like a cousin, a closer relative to the Mauritius St. Aubin blanc (for example). What it lacked in pungency it made up for in both subtlety and harmony, even at 50%.

It was also surprisingly sippable for what it was, very approachable, and here again I’ll comment on what a good strength 48-52% ABV is for such white rums. It presented as sweet and light, perfumed with flowers, pears, green grapes and apple juice, then adding some sour cream, brine, olives and citrus for edge. There were some reticent background notes as well, cinnamon mostly, and an almost delicate vein of citrus and ginger and anise. It tasted both warm and clean and was well balanced, and the finish delivered nicely, redolent of thyme, sweet vinegar dressing on a fresh salad, and green grapes with just a touch of salt.

Average to low end white mixers – still occasionally called silvers or platinums, as if this made any difference – are defined by their soft, unaggressive blandness: their purpose is to add alcohol and sink out of sight so the cocktail ingredients take over. In contrast, a really good white rum, which can be used either for a mixed drink or to have by itself if one is feeling a little macho that day, always has one or more points of distinction that sets it apart, whether it’s massive strength, savagery, rawness, pungency, smooth integration of amazing tastes, funk, clarity of flavour or whatever.

Honestly, I expected more of the latter, going in: something fiercer and more elemental…but I can’t say what was on display here was disappointing. In October 2018, when I asked him what rums he had that was of interest, Fabio actually tried to steer me away from this one (“It’s good, but not so interesting,” he laughed as he pulled down a Rare Caroni). But I disagreed, and think that what it really comes down to is that it’s a solid addition to the white portion of the rum spectrum and certainly a step above “standard”. It’s tasty and warm, and manages the cute trick of being dialled down to something really approachable, while still not forgetting its more uncouth antecedents. And if it is not of the pungent power that can defoliate a small patch of jungle, well, it may at least blanch a leaf or two, and is worth taking a second look at, if it crosses your path.

(#560)(83/100)

Other Notes

From the 2017 release season

I’ll provide some more background detail in the Other Notes below, but for the moment let’s just read off the fact sheet for the rum which is very helpfully provided on the Rare Rums website and on the bottle label itself. This is a cane juice distillate and can therefore be classed as an agricole-style rhum; distilled 2009 and the four barrel outturn from a column still was aged in Madeira casks, providing 570 bottles in 2017, with a strength of 52%.

I’ll provide some more background detail in the Other Notes below, but for the moment let’s just read off the fact sheet for the rum which is very helpfully provided on the Rare Rums website and on the bottle label itself. This is a cane juice distillate and can therefore be classed as an agricole-style rhum; distilled 2009 and the four barrel outturn from a column still was aged in Madeira casks, providing 570 bottles in 2017, with a strength of 52%. In the last decade, several major divides have fissured the rum world in ways that would have seemed inconceivable in the early 2000s: these were and are cask strength (or full-proof) versus “standard proof” (40-43%); pure rums that are unadded-to versus those that have additives or are spiced up; tropical ageing against continental; blended rums versus single barrel expressions – and for the purpose of this review, the development and emergence of unmessed-with, unfiltered, unaged white rums, which in the French West Indies are called

In the last decade, several major divides have fissured the rum world in ways that would have seemed inconceivable in the early 2000s: these were and are cask strength (or full-proof) versus “standard proof” (40-43%); pure rums that are unadded-to versus those that have additives or are spiced up; tropical ageing against continental; blended rums versus single barrel expressions – and for the purpose of this review, the development and emergence of unmessed-with, unfiltered, unaged white rums, which in the French West Indies are called

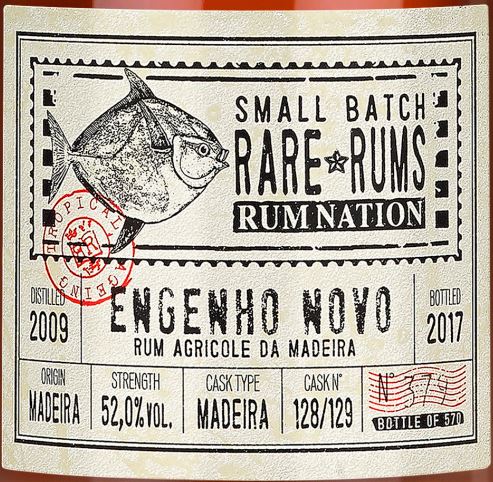

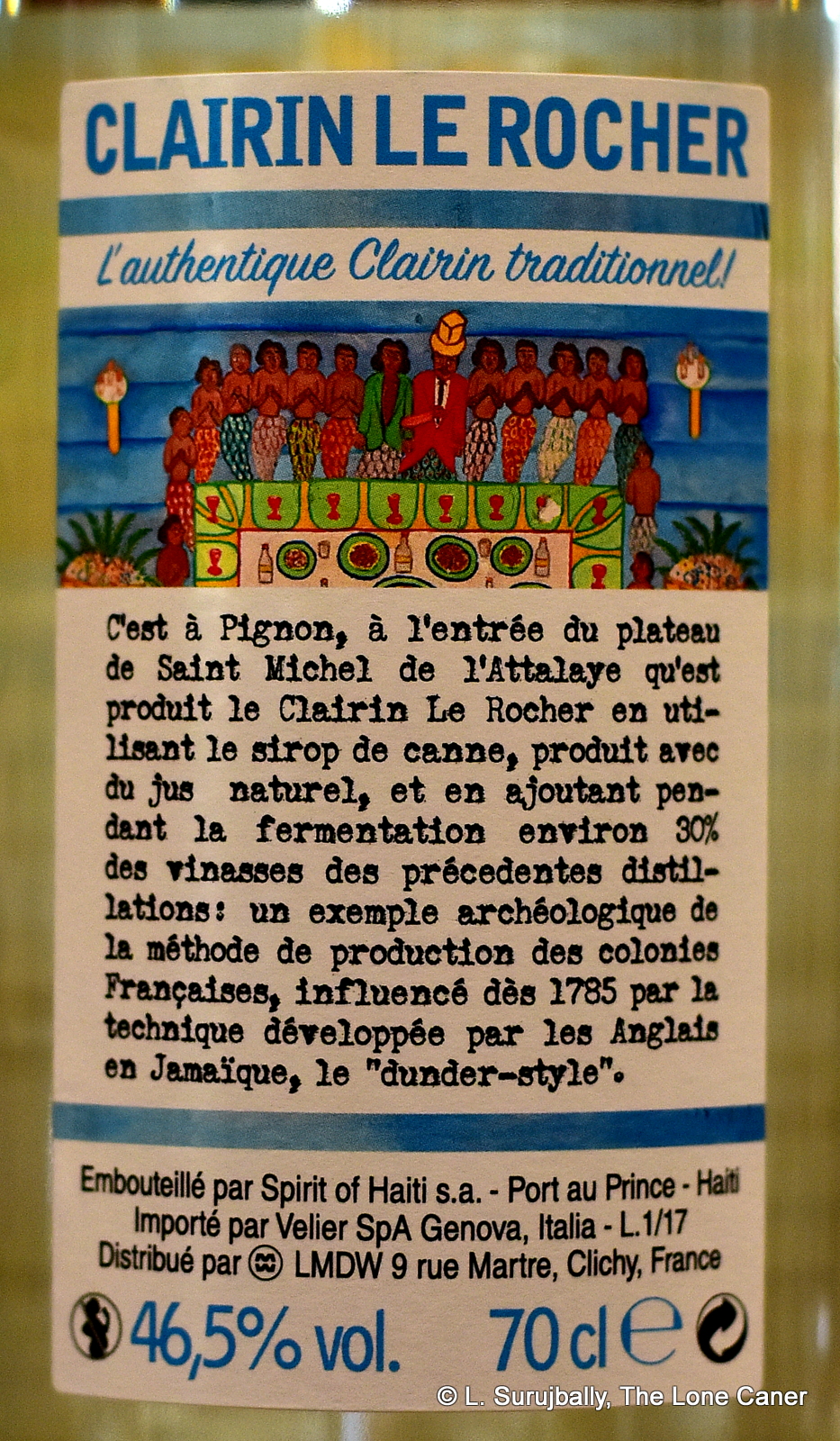

Well, that out of the way, let me walk you through the profile. Nose first: what was immediately evident is that it adhered to all the markers of a crisp agricole. It gave off of light grassy notes, apples gone off the slightest bit, watermelon, very light citrus and flowers. Then it sat back for some minutes, before surging forward with more: olives in brine, watermelon juice, sugar cane sap, peaches, tobacco and a sly hint of herbs like dill and cardamom.

Well, that out of the way, let me walk you through the profile. Nose first: what was immediately evident is that it adhered to all the markers of a crisp agricole. It gave off of light grassy notes, apples gone off the slightest bit, watermelon, very light citrus and flowers. Then it sat back for some minutes, before surging forward with more: olives in brine, watermelon juice, sugar cane sap, peaches, tobacco and a sly hint of herbs like dill and cardamom.

Sometimes a rum gives you a really great snooting experience, and then it falls on its behind when you taste it – the aromas are not translated well to the flavour on the palate. Not here. In the tasting, much of the richness of the nose remains, but is transformed into something just as interesting, perhaps even more complex. It’s warm, not hot or bitchy (46.5% will do that for you), remarkably easy to sip, and yes, the plasticine, glue, salt, olives, mezcal, soup and soya are there. If you wait a while, all this gives way to a lighter, finer, crisper series of flavours – unsweetened chocolate, swank, carrots(!!), pears, white guavas, light florals, and a light touch of herbs (lemon grass, dill, that kind of thing). It starts to falter after being left to stand by itself, the briny portion of the profile disappears and it gets a little bubble-gum sweet, and the finish is a little short – though still extraordinarily rich for that strength – but as it exits you’re getting a summary of all that went before…herbs, sugars, olives, veggies and a vague mineral tang. Overall, it’s quite an experience, truly, and quite tamed – the lower strength works for it, I think.

Sometimes a rum gives you a really great snooting experience, and then it falls on its behind when you taste it – the aromas are not translated well to the flavour on the palate. Not here. In the tasting, much of the richness of the nose remains, but is transformed into something just as interesting, perhaps even more complex. It’s warm, not hot or bitchy (46.5% will do that for you), remarkably easy to sip, and yes, the plasticine, glue, salt, olives, mezcal, soup and soya are there. If you wait a while, all this gives way to a lighter, finer, crisper series of flavours – unsweetened chocolate, swank, carrots(!!), pears, white guavas, light florals, and a light touch of herbs (lemon grass, dill, that kind of thing). It starts to falter after being left to stand by itself, the briny portion of the profile disappears and it gets a little bubble-gum sweet, and the finish is a little short – though still extraordinarily rich for that strength – but as it exits you’re getting a summary of all that went before…herbs, sugars, olives, veggies and a vague mineral tang. Overall, it’s quite an experience, truly, and quite tamed – the lower strength works for it, I think.

See, while furious aggression

See, while furious aggression

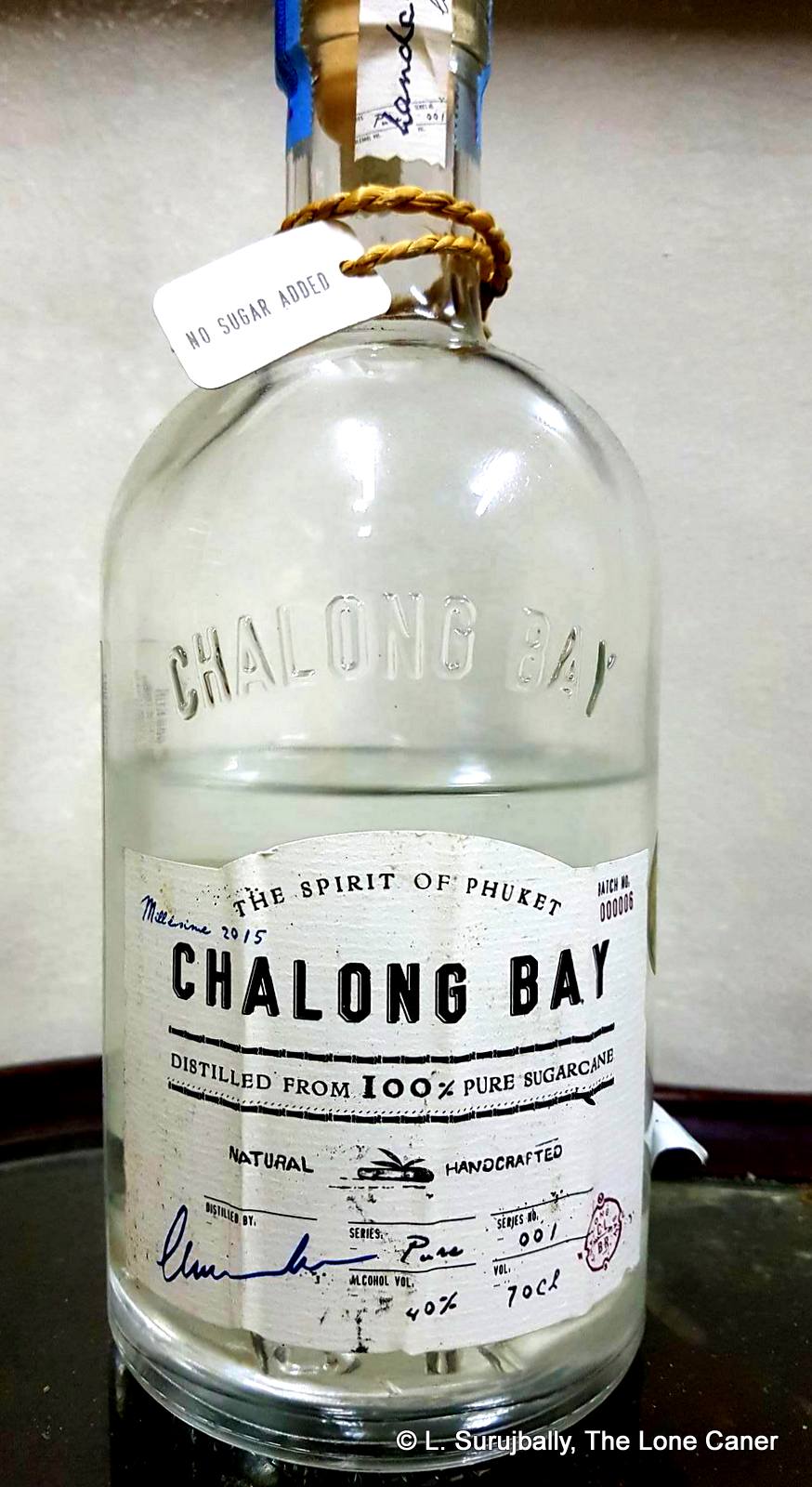

According to my email exchanges with the company, the rhum was produced from the harvest of 2005, and is a blend of two rhums – pot still (30%) aged ten years aged in ex-bourbon barrels, and column still (70%) stored in inert inox tanks; both distillates deriving from cane juice . As a further note, although sugar was explicitly communicated to me as

According to my email exchanges with the company, the rhum was produced from the harvest of 2005, and is a blend of two rhums – pot still (30%) aged ten years aged in ex-bourbon barrels, and column still (70%) stored in inert inox tanks; both distillates deriving from cane juice . As a further note, although sugar was explicitly communicated to me as