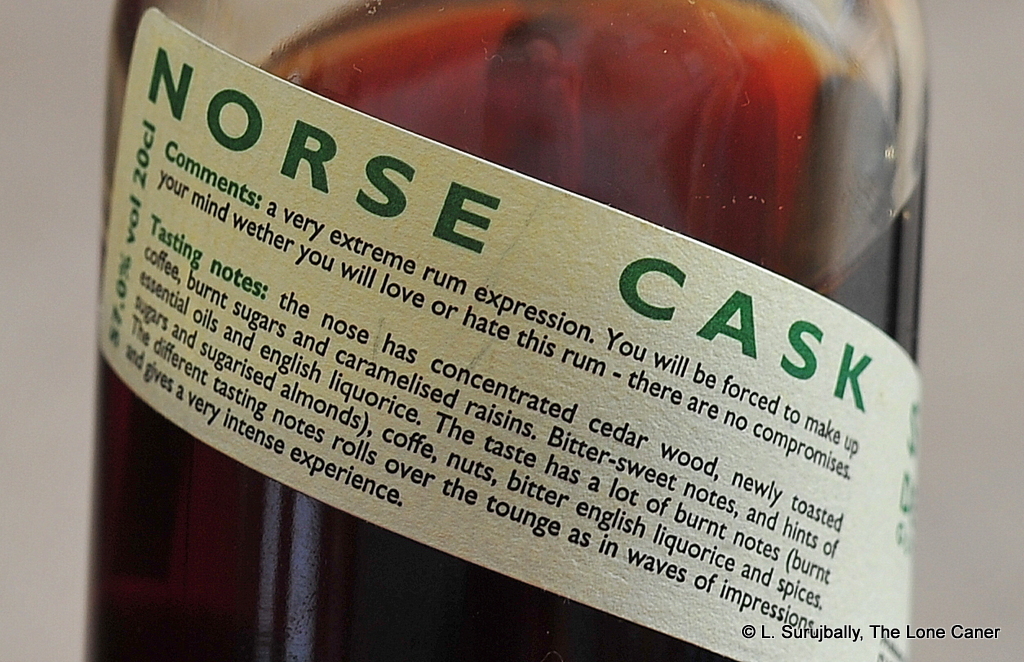

It’s instructive to drink the Norse Cask and the Cadenhead in tandem. The two are so similar except in one key respect, that depending on where one’s preferences lie, either one could be a favourite Demerara for life.

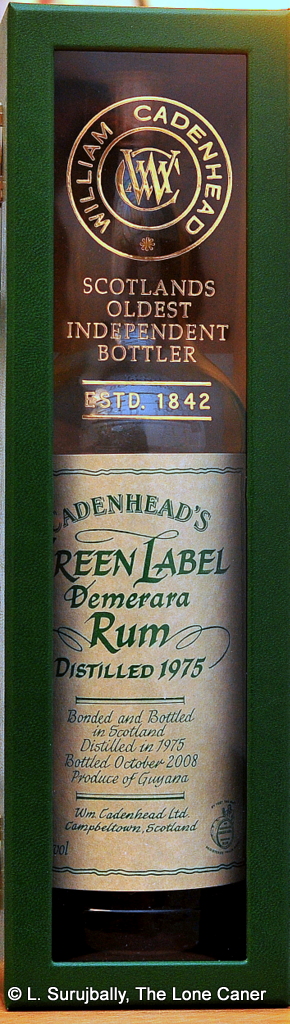

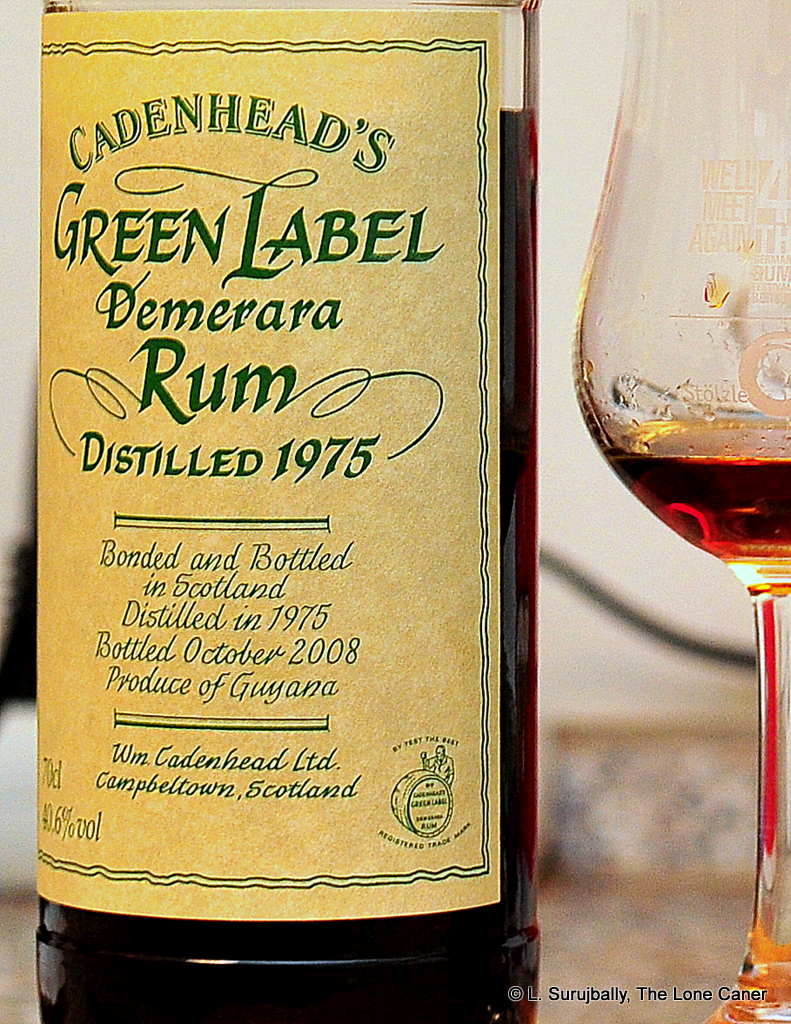

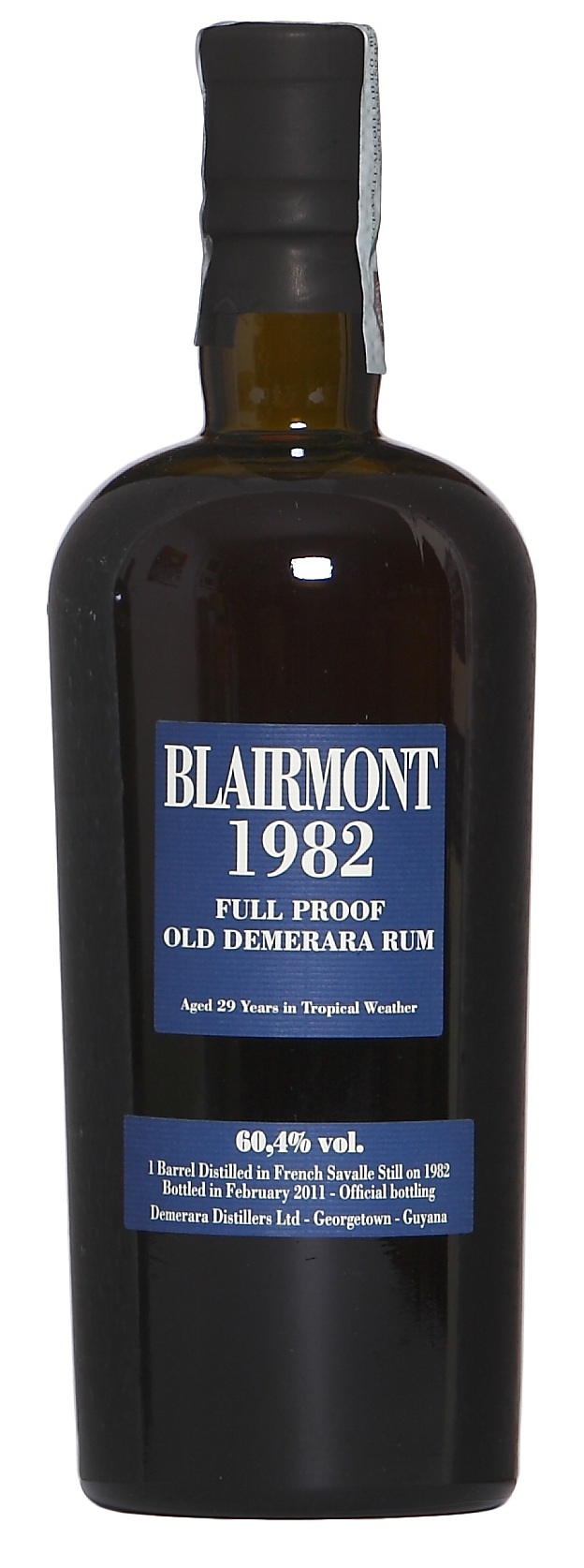

The online commentary on last week’s Norse Cask 1975 32 year old rum showed that there was and remains enormous interest for very old Guyanese rums, with some enthusiasts avidly collecting similar vintages and comparing them for super-detailed analyses on the tiniest variations (or so the story-teller in me supposes). For the benefit of those laser-focused ladies and gentlemen, therefore, consider this similar Cadenhead 33 year old, also distilled in 1975 (a year before I arrived in Guyana), which could have ascended to greatness had it been stronger, and which, for those who like standard strength rums of great age, may be the most accessible old Demerara ever made, even at the price I paid.

The dark mahogany-red Cadenhead rum was actually quite similar to the Norse Cask. Some rubber and medicinals and turpentine started the nose party going, swiftly gone. Then the licorice and tobacco — of what I’m going to say was a blend with a majority of Port Mourant distillate — thundered onto the stage, followed by a muted backup chorus of wood, oak, hay, raisins, caramel, brown sugar. I sensed apricots in syrup (or were those peach slices?). It’s the lack of oomph on the strength that made trying the rum an exercise in frustrated patience for me. I knew the fair ladies were in there…they just didn’t want to come out and dance (and paradoxically, that made me pay closer attention). It took a while to tease out the notes, but as I’ve said many times before, the PM profile is pretty unmistakeable and can’t be missed…and that was damned fine, let me reassure you, no matter what else was blended into the mix.

The dark mahogany-red Cadenhead rum was actually quite similar to the Norse Cask. Some rubber and medicinals and turpentine started the nose party going, swiftly gone. Then the licorice and tobacco — of what I’m going to say was a blend with a majority of Port Mourant distillate — thundered onto the stage, followed by a muted backup chorus of wood, oak, hay, raisins, caramel, brown sugar. I sensed apricots in syrup (or were those peach slices?). It’s the lack of oomph on the strength that made trying the rum an exercise in frustrated patience for me. I knew the fair ladies were in there…they just didn’t want to come out and dance (and paradoxically, that made me pay closer attention). It took a while to tease out the notes, but as I’ve said many times before, the PM profile is pretty unmistakeable and can’t be missed…and that was damned fine, let me reassure you, no matter what else was blended into the mix.

The palate demonstrated what the Boote Star 20 Year Old rum (coming soon to the review site near you) could have been with some additional ageing and less sugar, and what the Norse Cask could have settled for. The taste was great, don’t get me wrong: soft and warm and redolent with rich cascades of flavour, taking no effort at all to appreciate (that’s what 40.6% does for you). It was a gentle waterfall of dark grapes, anise, raisins, grapes and oak. I took my time and thoroughly enjoyed it, sensing even more fruit after some minutes – bananas and pears and white guavas, and then a slightly sharper cider note. The controlled-yet-dominant licorice/anise combo remained the core of it all though, never entirely releasing its position on top of all the others. And as for the finish, well, I wasn’t expecting miracles from a standard proof rum. Most of the profile I noted came back for their final bow in the stage: chocolate muffins drizzled with caramel, more anise, some slight zest…it was nothing earth-shattering, and maybe they were just kinda going through the motions though, and departed far too quickly. That’s also what standard strength will do, unfortunately.

That this is a really good rum is not in question. I tried it four or five times over the course of a week and over time I adjusted to its calm, easy-going voluptuousness. It’s soft, easygoing, complex to a fault and showcases all the famous components of profile that make the Guyanese stills famous. If one is into Demerara rums in a big way, this will not disappoint, except perhaps with respect to the strength. Some of the power and aggro of a stronger drink is lost by bottling at less than 41% and that makes it, for purists, a display of what it could have been, instead of what it is. I suggest you accept, lean back and just enjoy it. Neat, of course. Ice would destroy something of its structural fragility, and mixing it might actually be a punishable offense in some countries.

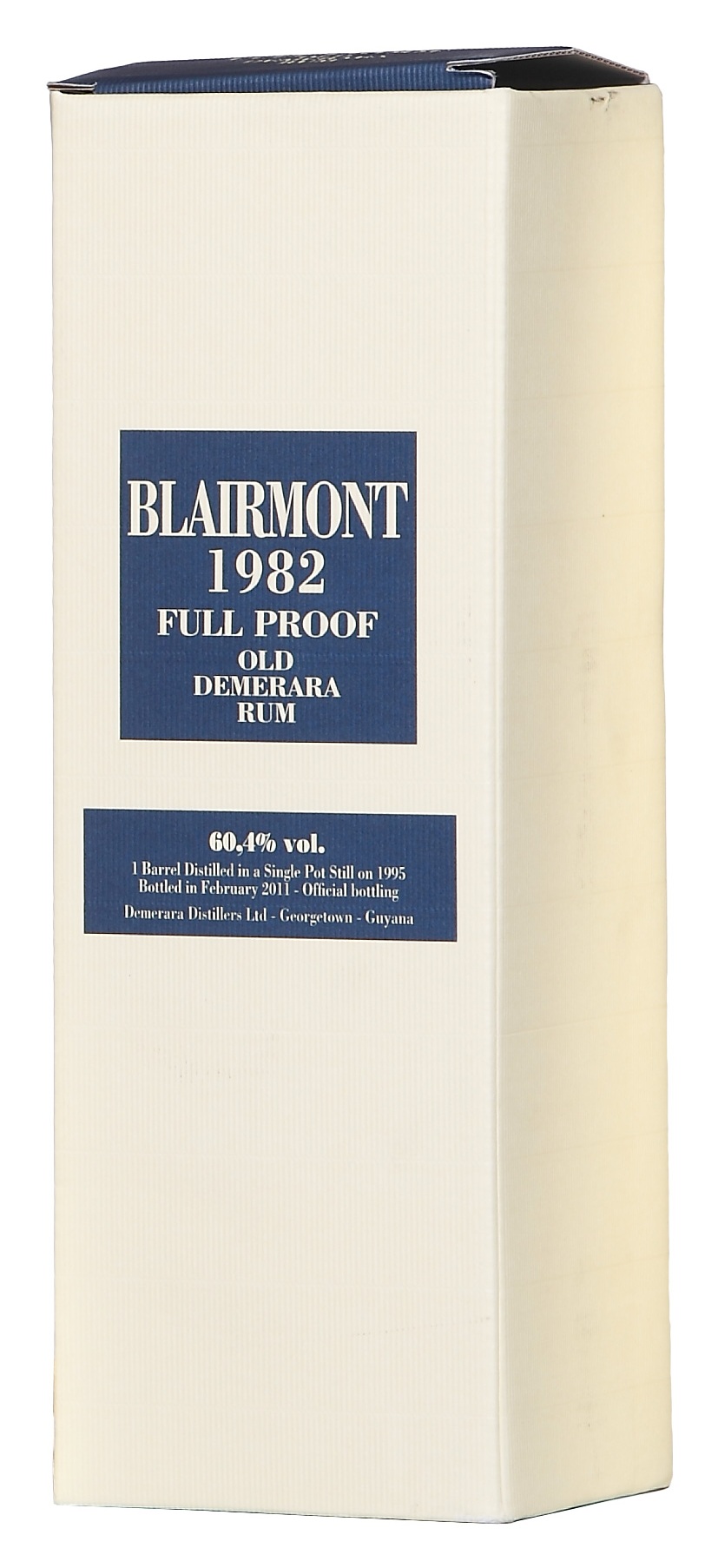

The word “accessible” I used above does not mean available, but relatable. The majority of the rum drinking world does not in fact prefer cask strength rums, however much bloggers and aficionados flog the stronger stuff as better (in the main, it is, but never mind). Anyway, most people are quite comfortable drinking a 40-43% rum and indeed there are sterling representatives at that strength to be found all over the place. El Dorado’s 21 year old remains a perennial global favourite, for example – and that’s because it really is a nifty rum at an affordable price with an age not to be sneered at (it succeeds in spite of its adulteration, not because of it). But most of the really old rums for sale punch quite a bit higher, so for those who want to know what a fantastically good ancient Demerara is like without getting smacked in the face by a 60% Velier, here’s one to get. It’s a love poem to Guyanese rums, reminding us of the potential they all have.

The word “accessible” I used above does not mean available, but relatable. The majority of the rum drinking world does not in fact prefer cask strength rums, however much bloggers and aficionados flog the stronger stuff as better (in the main, it is, but never mind). Anyway, most people are quite comfortable drinking a 40-43% rum and indeed there are sterling representatives at that strength to be found all over the place. El Dorado’s 21 year old remains a perennial global favourite, for example – and that’s because it really is a nifty rum at an affordable price with an age not to be sneered at (it succeeds in spite of its adulteration, not because of it). But most of the really old rums for sale punch quite a bit higher, so for those who want to know what a fantastically good ancient Demerara is like without getting smacked in the face by a 60% Velier, here’s one to get. It’s a love poem to Guyanese rums, reminding us of the potential they all have.

(#260. 87.5/100)

Other notes

- 2025 Video Recap

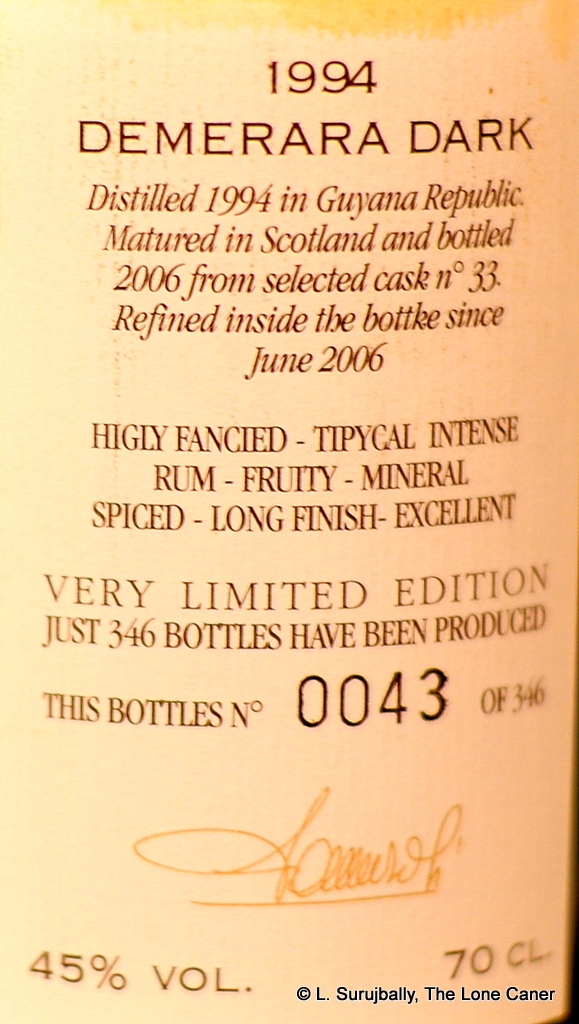

- Distilled 1975, bottled October 2008. Outturn is unknown.

- The actual components and ratios of the blend is also not disclosed anywhere.

- The rum arrived in a cool green box with a brass clasp. And a cheap plastic window. Ah well…

- Cadenhead has several versions of the 1975:

- Green Label Demerara 30 YO (1975 – 2005), 40,5% vol.

- Green Label Demerara 32 YO (1975 – 2007), 40,3% vol.

- Green Label Demerara 33 YO (1975 – 2008), 40,6% vol.

- Green Label Demerara 36 YO (1975 – 2012), 38,5% vol.

- Green Label Demerara 35 YO (1975 – 2010), 40.0% vol.

A very well blended, original melange of traditional Demerara flavours that comes up to the bar without effort, but doesn’t jump over.

A very well blended, original melange of traditional Demerara flavours that comes up to the bar without effort, but doesn’t jump over.

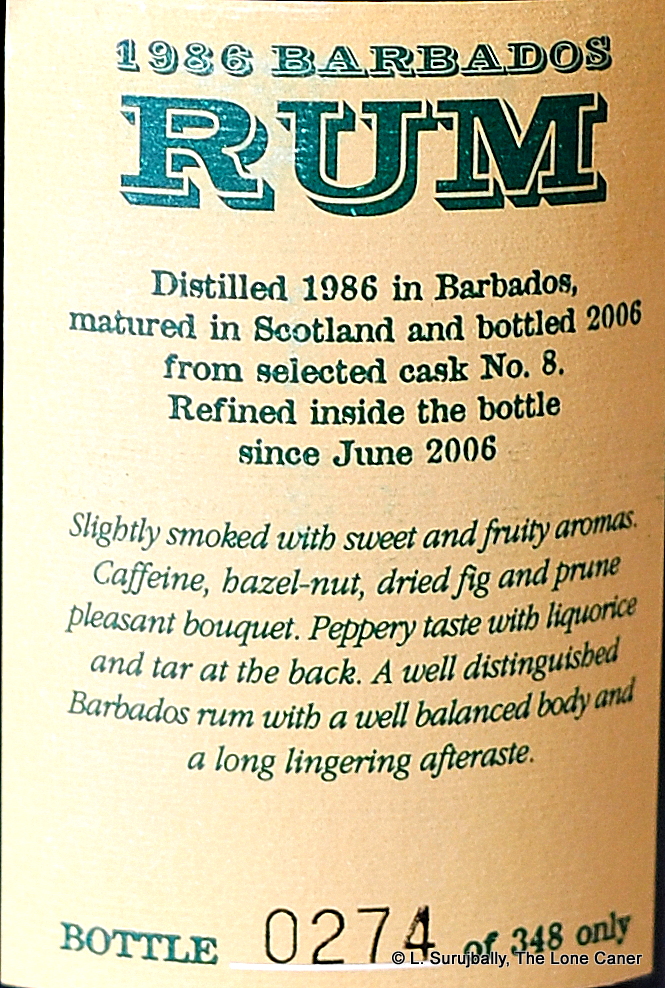

Rumaniacs Review 018 | 0418

Rumaniacs Review 018 | 0418

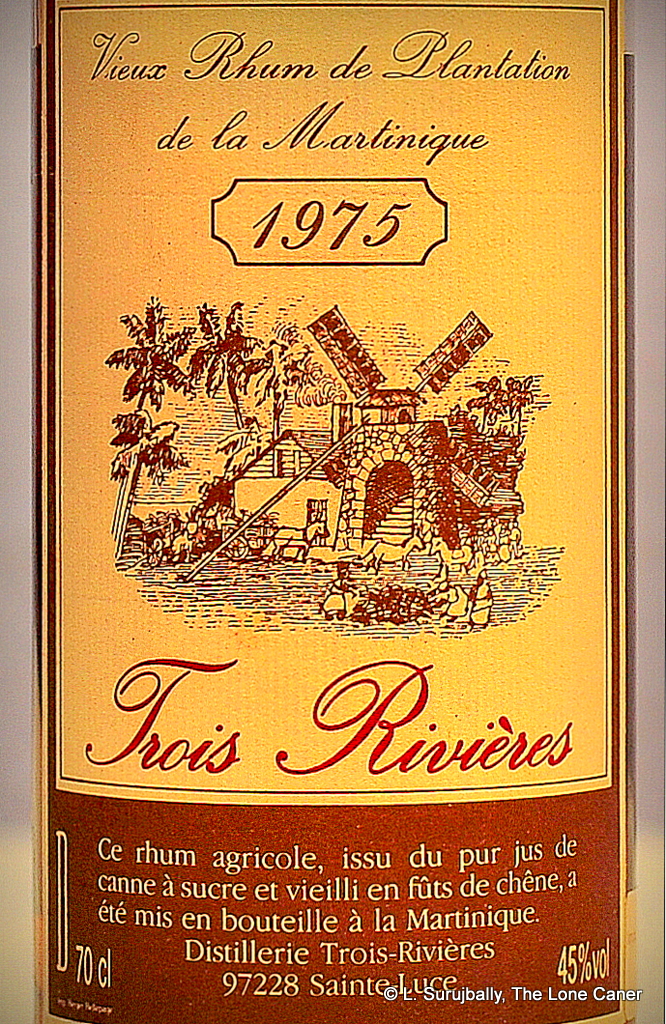

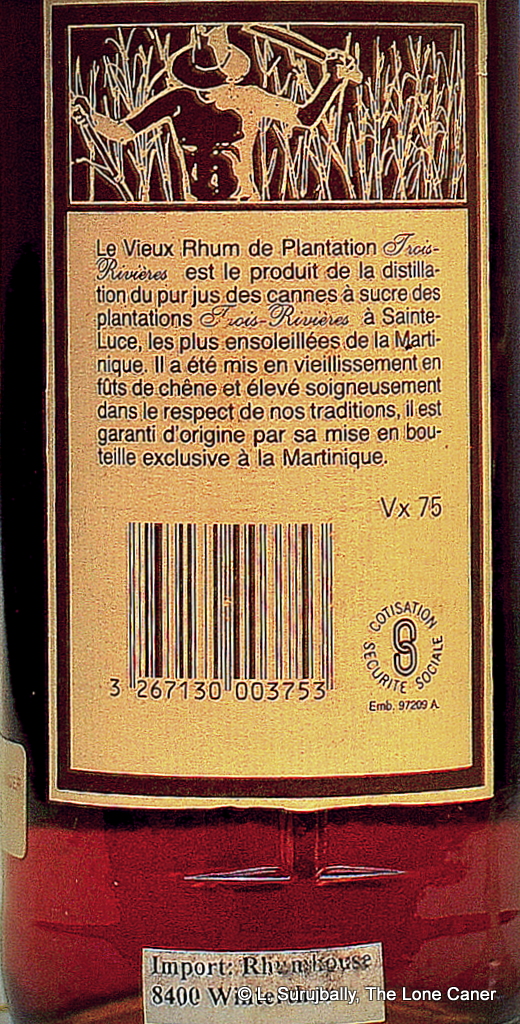

Rumaniacs Review 017 | 0417

Rumaniacs Review 017 | 0417

palled my enjoyment somewhat.

palled my enjoyment somewhat.

Rumaniacs Review 016 | 0416

Rumaniacs Review 016 | 0416

The question I asked of the 1975 (which I was using as a control alongside the Rhum Rhum Liberation Integrale, the

The question I asked of the 1975 (which I was using as a control alongside the Rhum Rhum Liberation Integrale, the

out ever letting you forget they existed. Salt beef in brine, red olives, grass, tannins, wood and faint smoke were more readily discernible, mixed in with heavier herbs like fennel and rosemary. These well balanced aromas were tied together by duskier notes of burnt sugar and vanillas and as it stood and opened up, slow scents of cream cheese and marshmallows crept out to satisfy the child within.

out ever letting you forget they existed. Salt beef in brine, red olives, grass, tannins, wood and faint smoke were more readily discernible, mixed in with heavier herbs like fennel and rosemary. These well balanced aromas were tied together by duskier notes of burnt sugar and vanillas and as it stood and opened up, slow scents of cream cheese and marshmallows crept out to satisfy the child within.

Rumaniacs Review 015 | 0415

Rumaniacs Review 015 | 0415

grassy elements in the background, serving to swell a note or two without ever dominating the symphony

grassy elements in the background, serving to swell a note or two without ever dominating the symphony