Part of the problem The major problem I have with this rum is that it simply tastes artificial – “fake,” in today’s updated lexicon – and that’s entirely aside from its labelling, which we’ll get into in a minute. For the moment, I’d suggest you follow me through a quick tasting, starting with a nose that reminds one disconcertingly of a Don Papa – oak, boatloads of vanilla, icing sugar, honey, some indeterminate fleshy fruits and more vanilla. This does not, I’m afraid, enthuse.

In spite of its 46.5% strength (ah, the good old days when this was considered “daring” and “perhaps a shade too strong”), the taste provided exactly zero redemption. There’s a lot going on here — of something — but you never manage to come to grips with it because of the dominance of vanilla. Sure there’s some caramel, some molasses, some ice cream, some sweet oatmeal cookies, even a vague hint of a fruit or two (possibly an orange was waved over the spirit as it was ageing, without ever being dropped in) – but it’s all an indeterminate mishmash of nothing-in-particular, and the short finish of sweet, minty caramel and (you guessed it) vanilla, can at best be described as boring.

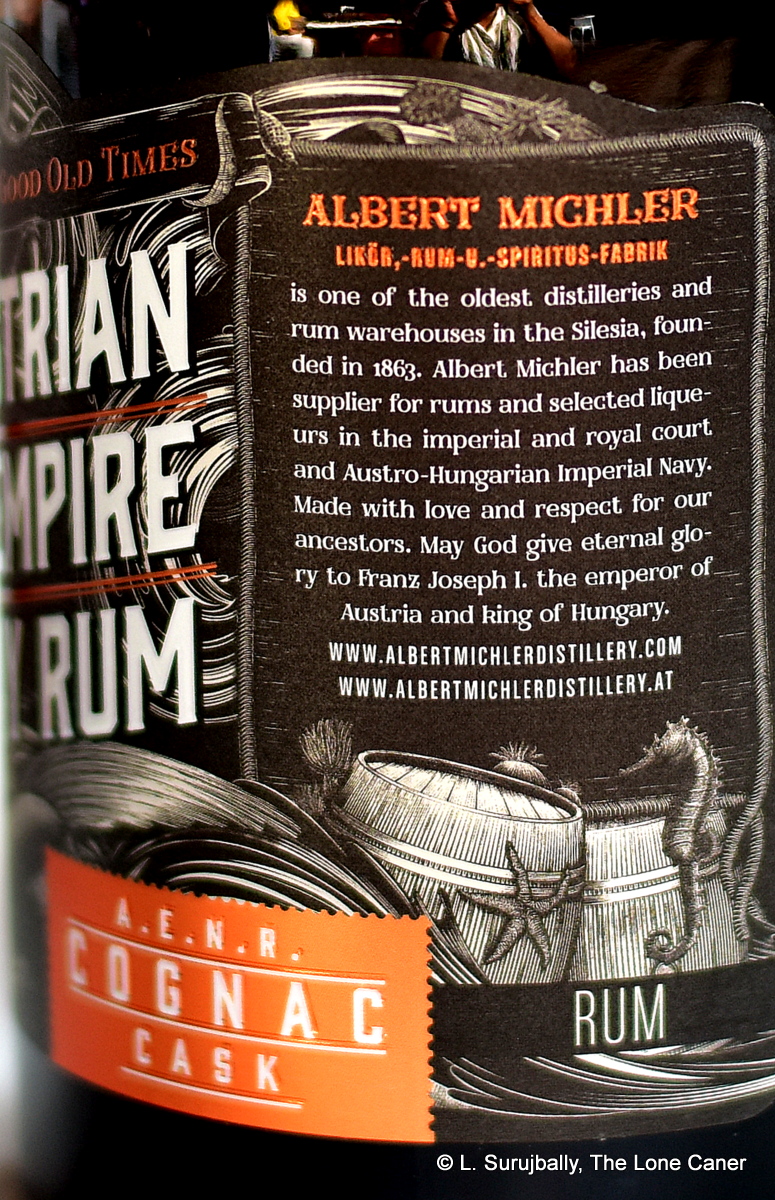

So, some background then. The rum is called “Austrian Empire Navy Rum” and originally made by Albert Michler, who established a spirits merchant business in 1863, four years before the Austrian Empire became the Austro-Hungarian Empire…so he had at best four years to create some kind of naval tradition with the rum, which is unlikely. Since the company started with the making of a herbal liqueur before moving into rums, a better name for the product might be “Austro-Hungarian Navy Rum” – clearly this doesn’t have the same ring to it, hence the modern simplification, evidently hoping nobody cared enough to check into the datings of the actual empire. For the record, the company which had been based in Silesia (in Czechoslovakia) limped on after WW2 when the exodus of German speaking inhabitants and the rise of the communists in 1948 shuttered it. The new iteration appears to have come into being around 2015 or so.

There are no records on whether the Austrian or Austro-Hungarian Navy ever used it or was supplied by the Michler distillery. Somehow I doubt it – it was far more likely it followed in the tradition of rum verschnitt, which was neutral alcohol made from beets, tarted up with Jamaican high ester DOK, very popular and common around the mid to late 1800s in Germany and Central Europe. The thing is, this is not what the rum is now: a blended commercial product, it’s actually a sort of hodgepodge of lots of different things, all jostling for attention – a blended solera, sourced from Dominica, aged in french oak and american barrels “up to 21 years,” plus 12-16 months secondary ageing in cognac casks …it’s whatever the master blender requires. It cynically trades in on a purported heritage, and is made by a UK based company of the same name located in Bristol, and who also make a few other “Austrian Navy” rums, gin, absinthe and the Ron Espero line of rums.

There are no records on whether the Austrian or Austro-Hungarian Navy ever used it or was supplied by the Michler distillery. Somehow I doubt it – it was far more likely it followed in the tradition of rum verschnitt, which was neutral alcohol made from beets, tarted up with Jamaican high ester DOK, very popular and common around the mid to late 1800s in Germany and Central Europe. The thing is, this is not what the rum is now: a blended commercial product, it’s actually a sort of hodgepodge of lots of different things, all jostling for attention – a blended solera, sourced from Dominica, aged in french oak and american barrels “up to 21 years,” plus 12-16 months secondary ageing in cognac casks …it’s whatever the master blender requires. It cynically trades in on a purported heritage, and is made by a UK based company of the same name located in Bristol, and who also make a few other “Austrian Navy” rums, gin, absinthe and the Ron Espero line of rums.

That anything resembling a rum manages to crawl out of this disorganized blending of so many disparate elements is a sort of minor miracle, and I maintain it’s less a rum than the cousin of the Badel Domaci, Tuzemak, Casino 50⁰ and other such domestic “Rooms” of Central Europe….even if made in Britain. It is therefore very much made for its audience: it will likely find exactly zero favour with anyone who likes a purer experience exemplified by modern Caribbean rums and new micro distilleries the world over, but anyone who likes sweet supermarket rums (possibly spiced up) will have no issue with it at all. I’m not one of the latter, though, since I personally prefer to stick with reputable houses that make, y’know, real rums.

(#734)(70/100)

Other notes

The company website makes no mention of additives or spices. My sense that it is a rum with stuff added to it is my interpretation based on the taste profile and not supported by any published material.