Introduction

One of the rum-producing countries about which we don’t know enough is India, home of companies like Rhea, Amrut, Radico Khaitan, Krimpi, Tilaknagar, McDowell’s (part of Diageo) and the subject of today’s biography, Mohan Meakin. Originally it was to form part of the review of their Old Monk Supreme XXX Vatted Rum, but when I delved into the weeds, the “tale grew in the telling” until it was clear that it deserved a full treatment by itself.

The Founders and Early Years

The company that eventually became Mohan Meakin was founded by a Scottish businessman named Edward Abraham Dyer. He was the son of a British officer, John Dyer, who served in the East India Company’s Naval Service (and whose father in turn had served in the Royal Navy in the 18th century) and had lived in India from around the 1820s. Edward Dyer, born in Bengal (c.1830), was educated in England as an engineer but did not seem to want to pursue a military career and returned to India around 1850 (or earlier, there’s some confusion here). With his brother John he determined to use his family money to open a brewery, as to this point beer could only come to India around the Cape of Good Hope and this made it prohibitively expensive. One attempt to brew had been made in a hamlet called Kasauli south of Shimla in the northern Indian province of Himachal Pradesh, but it had failed in the 1840s.

Kasauli Brewery. Photo (c) Havinder Chandigarh

Kasauli became a cantonment and hill station of the British East India Company in 1845 (India had not yet been taken over by the British Crown), and Dyer set up his initial beer brewery there, Asia’s first. He chose the site because it was the location of the previous failed attempt, was similar in climate to his Scottish homeland, had a good supply of pure springwater, and (perhaps more importantly) a ready supply of British “John Company” troops and civilians in Shimla and elsewhere in the Punjab. His intention was initially to make beer, but expanded that idea to ale and whisky as well. He brought brewing and distilling equipment (including pot stills, some of which are still in use today) from Britain by steamer, ship and ox carts, up the Ganges and to Shimla, thence to Kasauli; once set up, he began making whisky, India Pale Ale, and Lion beer, the latter also being a first in all Asia.

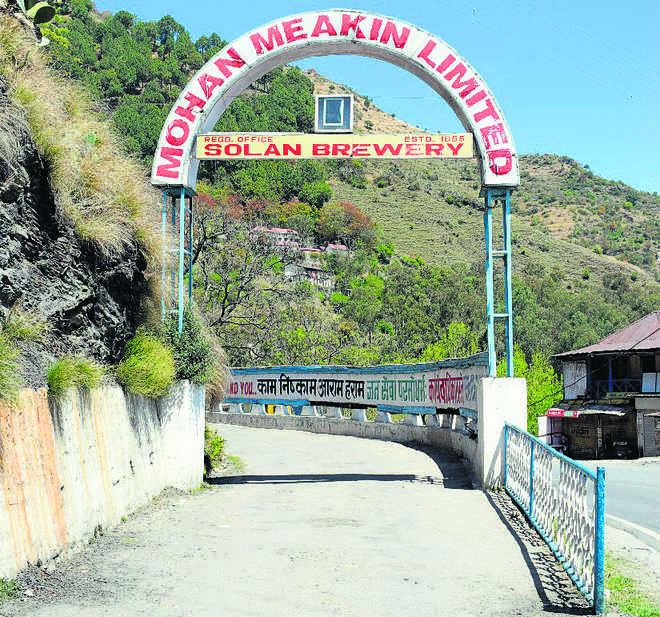

As Kasauli began using most of the springwater to supply its growing population, the brewery was dismantled and moved to Solan, 10km to the east, further downhill and closer to both the railhead and better water supply, while leaving the distillery in place, and both distillery and brewery remain operational to the current time. At the inception the brewery/distillery had simply been named the Kasauli Brewery. However, after the British East India Company annexed the Punjab in 1849 (this highanded action was part of what led to the 1857 mutiny) and British law extended to it, including company law, Dyer incorporated the company as Dyer Breweries Limited in 1855 which is the date seen on MM’s logo to this day, though the exact date of the company’s true operational inception remains somewhat unclear…it’s very likely earlier (sources conflict – see other notes, below).

Original Pot stills used for making whisky (c) smacindia.com

The distillery initially made the well regarded malt whisky called “Solan No. 1” which took the name of the nearby town to which the brewery subsequently relocated, and this remained the best selling Indian whisky until the 1980s when new rivals toppled it. The ale and beer and whisky made by Dyer’s were so popular that he was able to expand rapidly. In the following decades, to add to the ones at Kasauli and Solan, he established breweries and distilleries at Lucknow (in Uttar Pradesh), Mandalay in Burma (now Myanmar), Murree, Rawalpindi and Quetta (in Pakistan – where Murree Brewery remains that country’s largest and oldest manufacturer of alcoholic products and is now a public company); and interests in yet more companies in southern India and Ceylon.

As a not-entirely-irrelevant aside, the Dyers were considered second class British at best, commercial creatures, being as they were “box-wallahs” (“in the trade” – both terms were ones of condescension and contempt) and not either Government or military — and this was looked down upon in the caste-ridden British society of the day. Unsurprisingly this would have led them in turn to denigrate all Indians as their inferiors, an attitude strengthened by the fear engendered by the Rising (aka the Mutiny) of 1857. Indians were considered beneath notice, whether servants, employees or independent suppliers of sugar cane, like the ancestors of Indy and Jazz Singh of Skylark Spirits, who, according to family legend, supplied the brewery when it started to make rum. And this in turn undoubtedly influenced the mentality of General Reginald Dyer, Edward’s son, who earned for himself the sobriquet of “The Butcher of Amritsar” for having his soldiers fire into an unarmed crowd in 1919. This was considered a fatal blow to British rule in India and led to both independence in 1947, and the takeover of the company in 1949 by Indians, as well as the emigration of many Indians like the Singhs’ parents, to Britain.

While the Dyer name contained within the original company title has vanished (see below), the other half has proved more durable, and lasted to the present day. Unfortunately, considerably less is recorded or known about H.G. Meakin as a person (including what the “H.G” actually stands for – one comment [below] says it stood for “Herery George”) than about Edward Dyer, in spite of his achievements being as great.

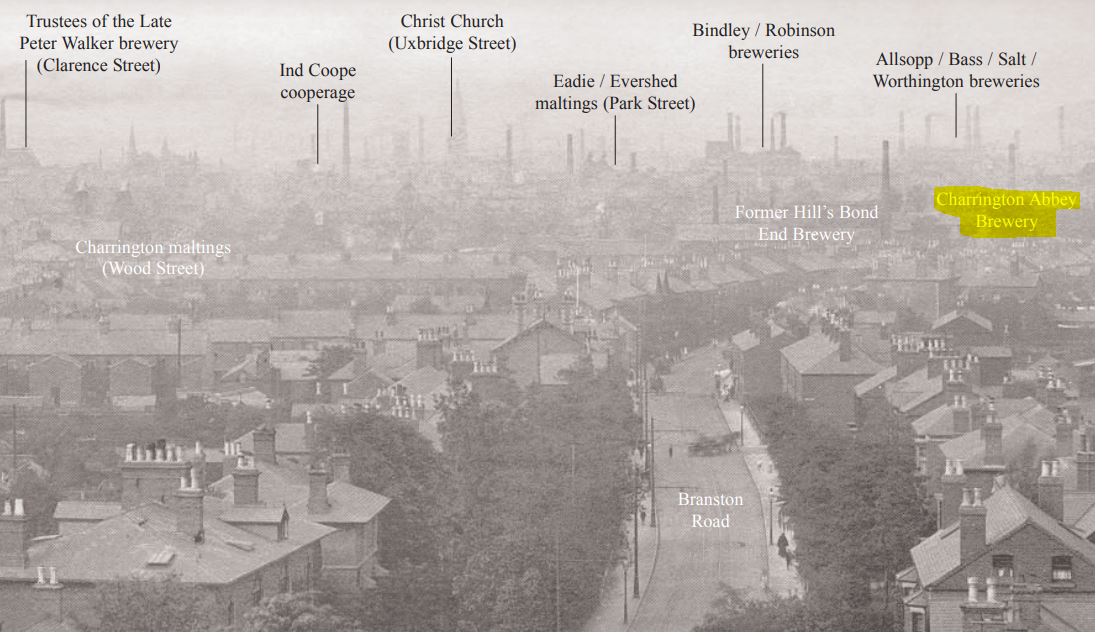

In origins, it is recorded that Meakin came from a successful brewing family in Burton-on-Trent in Staffordshire, England, which is quite an interesting place in its own right. It has a long history of beer making and many small breweries there going back centuries, with the Meakin name traceable as far back as 1726 when they were brewers and victuallers, in which line of business they continued until Charrington bought them out in 1872 … after which the trail gets chilly. The problem is, H.G. Meakin is not referenced anywhere, and even the Lewis Meakin genealogy from the early 1800s lists no direct relative with the initials H.G. (the comment below states he was the grandson of Lewis Meakin). Yet the Mohan Meakin website and other sources state that he came from Burton-on-Trent, was related to the Meakins and had brewery training as a result of these connections.

Burton-Upon-Trent in 1905. The Charrington Abbey Brewery at right was taken over from the Meakins in 1872 (© The History Press; David Smith Collection).

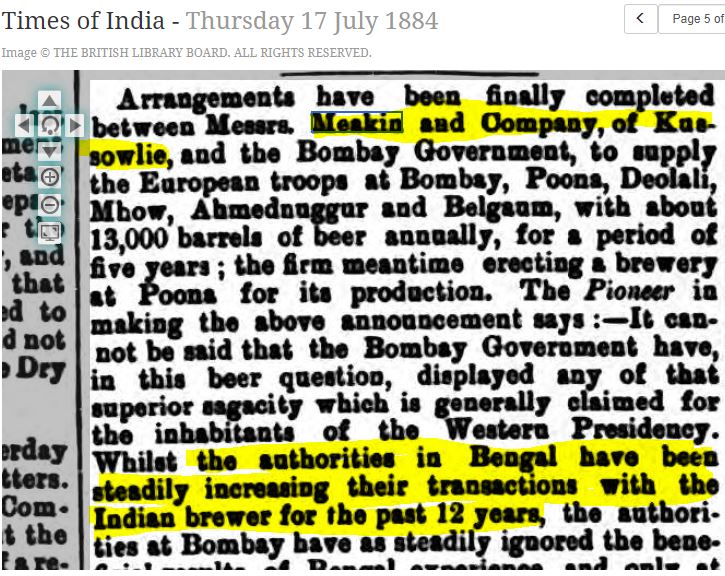

When he came to India, or what precisely he did when he got there, is another annoying mystery — the earliest reference to the company is an arrangement by the Bengal Government who were dealing with Meakin’s brewery for twelve years prior to 1884 when Meakin was already in “Kusowlie” (see image clipping below).

So by 1872 Meakin was there, and certainly by 1887 he must have been quite successful (or had gotten money via the family), because he had the financial resources to buy the Kasauli and Solan breweries from Dyer, who was seeking to expand elsewhere. If we assume Meakin was around 30-35 at this time – hustle and bustle in the business world attend to youth more than old age, especially in colonial India – then he was likely born in the 1840s and came to the subcontinent by the late 1860s / early 1870s. Over the next thirty years, Meakin bought or begun other spirits enterprises in Ranikhet, Dalhousie, Chakrata, Darjeeling, Kirkee and Nuwara Eliya (in what was then Ceylon, now Sri Lanka), creating an arc of production centres (mostly) in the northern highlands that spanned the entire subcontinent. Unsurprisingly, both Dyer’s and Meakin’s enterprises were established mostly in the cantonment towns where there were large numbers of British soldiers and Government officials who were in need of refreshment.

Distribution of Dyer’s and Meakin’s various distilleries and breweries prior to merging

The two businesses ostensibly went their separate ways after their commercial transaction in 1887, but the First World War was beneficial to both since their sales of beer and spirits rose significantly (aside from increased local sales in India, beer and malted barley were sent to Egypt for the armed forces and civilians there), and there is some indication of cooperation between them at this time. It is easy, therefore, to imagine the Dyers (not Edward – he had probably passed away by this time) and the Meakins getting together to discuss a combined future, and in the 1920s they established a joint venture called Dyer Meakin & Co. Ltd – clearly the darkness of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre by Edward’s son Reginald, had not extended far enough to besmirch the Dyer name or cause it to be discreetly retired from the company masthead.

A consequence of this joint venture was that operations were restructured: brewing was suspended at Kasauli while upgraded, modernized and extended at Solan, and extensive malting continued at Kasauli. As the years moved on, modernization permitted increased production with the latest machinery and apparatus, and some of the unprofitable brewing centres were shuttered, with Solan, Kasauli and Lucknow being greatly expanded. Also, in April 1937, Burma became a separately administered colony of Great Britain, and operations there had to be separated from those of India for tax and administrative reasons. The Joint Venture at this point was retired and became a merged public company which was renamed with a complete lack of originality, to Dyer Meakin Breweries Ltd and this was listed on the London Stock Exchange.

A consequence of this joint venture was that operations were restructured: brewing was suspended at Kasauli while upgraded, modernized and extended at Solan, and extensive malting continued at Kasauli. As the years moved on, modernization permitted increased production with the latest machinery and apparatus, and some of the unprofitable brewing centres were shuttered, with Solan, Kasauli and Lucknow being greatly expanded. Also, in April 1937, Burma became a separately administered colony of Great Britain, and operations there had to be separated from those of India for tax and administrative reasons. The Joint Venture at this point was retired and became a merged public company which was renamed with a complete lack of originality, to Dyer Meakin Breweries Ltd and this was listed on the London Stock Exchange.

The writing was, however, on the wall for Empire, which was now on its last legs. The Great War had drained Britain of an entire generation of young men, and nearly bankrupted it. The next war finished the job and part of the conditions for American help during WW2 was for Britain to relinquish its empire and move the colonies towards self-government and independence, a task that was accomplished, but bloodily, and with great loss of life – especially in India and the disaster that was Partition.

Indian Ownership: Post-Independence

I am unclear what economic restrictions attended to Britons who owned property and businesses in India at Independence in 1947, but most of my reading suggests wholesale expropriation was not on the cards and British businesses were allowed to continue much as before. Nevertheless, it could not have been easy for such companies to function in a “we got ours now” environment where thousands of British families had already returned “home,” and where a fierce nationalism and dislike of all things colonial pervaded the business and professional atmosphere.

It is likely for this reason, and perhaps also other subtle (and not so subtle) pressures brought to bear, that those family members of Meakins and Dyers remaining with the company, decided to dispose of their interest, and when a Brahmin ex-employee Narendra Nath Mohan raised appropriate funds and came to London in 1948, they made a deal to sell their shares (no further details available) and Mohan took ownership in 1949. The modern era of Mohan Meakin dates from this point, yet, interestingly, the name did not change and it remained Dyer Meakin Breweries for another seventeen years and the company did not diversify its alcoholic production into other areas for another five.

It is likely for this reason, and perhaps also other subtle (and not so subtle) pressures brought to bear, that those family members of Meakins and Dyers remaining with the company, decided to dispose of their interest, and when a Brahmin ex-employee Narendra Nath Mohan raised appropriate funds and came to London in 1948, they made a deal to sell their shares (no further details available) and Mohan took ownership in 1949. The modern era of Mohan Meakin dates from this point, yet, interestingly, the name did not change and it remained Dyer Meakin Breweries for another seventeen years and the company did not diversify its alcoholic production into other areas for another five.

NN Mohan built new breweries in Lucknow, Khopoli (near Mumbai) and Ghaziabad (in Uttar Pradesh). In the decades that followed, he created a sort of industrial hub in Ghaziabad for what would be a conglomerate, and expanded into other (sometimes self reinforcing) lines of businesses – brewery, distillery, malt house, glass factory, an ice factory and engineering works. Clearly, the man had great vision for the future and did not intend to stay with just what he had bought.

However, up to that point, the products made by the company remained what they always had been – whisky and beer. These were popular – Lion and Golden Eagle beers remained the most widely sold in India, with Solan No.1 doing the honours for whisky – but that was it. In the early 1950s, in an effort to diversify, NN and one of his three sons, Ved Ratan Mohan (“VR”), came up with what would become one of their signature, flagship brands, the Old Monk rum. VR, 26 at the time, wanted to channel inspiration he had taken from Benedictine monks in Europe, as well as to take on the Hercules rum sold exclusively to the armed forces (he retired a Colonel himself).

However, up to that point, the products made by the company remained what they always had been – whisky and beer. These were popular – Lion and Golden Eagle beers remained the most widely sold in India, with Solan No.1 doing the honours for whisky – but that was it. In the early 1950s, in an effort to diversify, NN and one of his three sons, Ved Ratan Mohan (“VR”), came up with what would become one of their signature, flagship brands, the Old Monk rum. VR, 26 at the time, wanted to channel inspiration he had taken from Benedictine monks in Europe, as well as to take on the Hercules rum sold exclusively to the armed forces (he retired a Colonel himself).

With his father, he created the blend of rums aged (oak-vats) for seven years (it is unclear where the initial stock originated, one of many such unknowns that were okay then but certainly not now) and infused with undisclosed spices (another aspect never mentioned). Initially the idea was standard barroom bottles but VR liked the crinkled squat Old Parr whisky bottles and appropriated their design, later settling a court case with Old Parr to allow them (MM) to keep the transparent variation.

Picture provided courtesy of reddit user /biggunbuster

Note the “Made in Punjab only” and “For sale to paramilitary forces only” statements

The Old Monk rum was at first released in December 1954, and issued in limited quantities to the armed forces, where it shattered class barriers that heretofore had relegated rum to a jawan’s drink, not that of the officer class. By also positioning Old Monk as a more exclusive and upper class rum (especially by ensuring its availability in 5-star hotels), it became such a hit that distribution was expanded to the whole country, and it remained the best selling, most popular rum in India for the next fifty years, with other variations being added over the time.

The question of who exactly the Old Monk was, remains a matter of some conjecture and there are three stories [1] it’s a stylized Benedictine monk such as originally inspired V.R. Mohan [2] it represents one of the founders of the old house, H.G. Meakin himself, and is an homage to his influence, and [3] it represents a British monk who used to hang around the factory where the rums were made and aged, shadowing the master blender – his advice was so good that when Old Monk was first launched the name and bottle were based on him (this of course implies that aged rum was being made and sold by the company for years before 1954, but I simply have no proof of this and so cannot state it with assurance).

The company gradually expanded its repertoire of spirits, and while years of introduction are not known, the Solan No.1 brand has been joined by whiskies like Diplomat Deluxe, Colonel’s Special, Black Knight and Summer Hall. In keeping with many diversified companies, they also developed locally made gins like Big Ben and London Dry and Kaplanski vodka (implying a multi-column still had been put into operation) and an ever-expanding line of Old Monk series of rums.

The company itself, however, did not remain Dyer Meakin. The story goes that Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru refused to visit the brewery while touring Shimla in 1960 – when asked, he gave the predictable answer of it bearing the name of General Reginal Dyer with all its tragic and negative associations. It took another six years, but in 1966 it was renamed Moham Meakin Breweries, and in 1980, by now a conglomerate of some note, it was renamed again, to Mohan Meakin Ltd, and was subsequently listed on the Calcutta Stock Exchange, where it remains to this day.

The Modern Era of Ved Rattan Mohan and Kapil Mohan

Col. Ved Rattan Mohan

Management also changed. In 1969 Narendra Nath Mohan passed away, and his enterprising son Colonel Ved Rattan, took over. He was quite a character, apparently: a flamboyant bon vivant, he was an MP, mayor of Lucknow, chairman of Censor Board of Film Certification and even a favourite of Mrs Indira Gandhi — and parties held at his home were equally likely to be attended by Bollywood stars as by politicians. However, he had little time to make a mark on the company, as in 1973 he died at the young age of 45, and he had had just enough time to initiate the diversification of the companies into other food and beverage areas like cereals, fruit juices and mineral waters, which his successors would nurture and develop.

This put the management of the company in the hands of the second brother, Brigadier General Kapil Mohan, who at the time was heading up the marketing and distribution arm of the company, Trade Links. He was to lead Mohan Meakin for the next 42 years, until 2015 (he died in early 2018). He expanded the company’s liquor business, following from his brother’s innovations in other lines of F&B and led the company into the new century – albeit with mixed results.

Although a teetotaller himself, he ensured the vatted 7 YO Old Monk’s success by adding to the range, introducing a Deluxe XXX Rum, Gold Reserve, the Supreme XXX Rum, a white rum and Old Monk XXX Rum which I suppose is some low level standard that’s even cheaper than all the others. The brand of Old Monk rum went on to become a best selling rum, not just in India, but abroad. In the Indian Diaspora it was not unknown to have visiting friends be asked to bring a bottle over, as older folks recalled their first sips in college back in the day.

What was surprising that until very recently, the company did not advertise at all, claiming that they had no spare cash to waste and word of mouth would make it sell. That may be true, although the innate conservatism of the country (which did not even allow kissing onscreen in its movies until very recently) and the obvious restrictions of what it allowed and allows into advertising media surely played its part. Alcohol and cigarettes are currently not allowed on TV commercials, for example. Still, even with those restrictions at that time, the army remained a loyal bulk purchaser and their influence on the entire society made the affordable Old Monk rums to be continual and enormous sellers. The expanding line of alcohols and the cheap beers the company made did the rest.

The New Century – Threats, Opportunities, Declines

This could not, however, continue. India was slowly opening up to world trade after failure of the planned socialist economy of the 50s, 60s and 70s. It had flirted with Prohibition in the 1960s but it was soon lifted (alcohol remains illegal in a few places), and now other competitors were not only being allowed into the Indian market, but were springing up home grown. To this was added the increase in energy prices and export fees within India, which squeezed margins for the company.

Old Monk was the market leader until about 2002 — not just in the rum field (which it comfortably dominated to that point) but the entire branded spirits market in the whole country, including whisky. And that included the other large spirit combine (United Spirits) whisky named Bagpiper. Even McDowell’s “Celebration” rum sold barely 50% of what Monk moved and in India the Monk was almost an icon of the local drinking scene, a rite of drunken passage for young college grads, the way Bacardi or the Kraken is in other places now.

Old Monk was the market leader until about 2002 — not just in the rum field (which it comfortably dominated to that point) but the entire branded spirits market in the whole country, including whisky. And that included the other large spirit combine (United Spirits) whisky named Bagpiper. Even McDowell’s “Celebration” rum sold barely 50% of what Monk moved and in India the Monk was almost an icon of the local drinking scene, a rite of drunken passage for young college grads, the way Bacardi or the Kraken is in other places now.

By the mid 2000s the decline in the fortunes of the company’s flagship products was getting attention, some of which commentators and insiders laid at the feet of Kapil “Dad” and his no-advertising policy and his martial, regimented approach to innovation and development, which was ill suited to less restrictive and less traditional newcomers who played by nimbler and more innovative rules. Because, unlike Mohan Meakin, other domestic firms moved fast: United Spirits, Radico Khaitan, Allied Blender’s and Distillers, Tilak Nagar Industries, Khoday’s, Amrut Distilleries, John Distilleries, Simbhaoli Sugars, Empee Distilleries, Jagatjit Industries…they all added sparkle and pizzazz, new products, splashy marketing strategies, aggressive promotion, and they started to sell much better. The combination of canny advertising and clever market moves made McDowell’s Celebration move ahead — by 2011 it sold almost four times as much as Old Monk, in 2014 seven times as many units (15 million cases to 2 million).

Perhaps the Brigadier’s confidence originally had some foundation – Old Monk was not just a local seller (however much in decline) but an international favourite that actually outsold Bacardi in some places. But that didn’t matter because the finances of the company started to show losses between 2005-2015, the same period during which Old Monk’s share of the Indian rum market fell from 15% to 5%. There were brief lurches into profit as MM divested land and other assets but overall no significant moves were made to revamp the lineup or change the business strategy or allow advertising on a level other companies were doing (“We do not advertise. I will not, and as long as I am in this chair, we will not,” huffed the 84-year-old Mohan in 2012, believing then as before, that a good product is its own advertisement).

And the hits just kept on coming:

Mohan Meakin suffered the shutdown of the Lucknow brewery and distillery almost overnight in 2009 (caused by Wave Distilleries’ Ponty Chada getting a near monopoly of the liquor business in what can only be described as an underhand political deal – clearly India has nothing to learn from Barbados when it comes to cutthroat business practices and skullduggery); Tamil Nadu’s state took over all liquor procurement and sales (which all but removed Old Monk from state shelves for years in one of the most resolutely rum-drinking markets in India); perhaps worse, Indians were drinking less rum and switching to whisky as the move towards premiumization began; and to add insult to injury, the Indian Army, long a bastion of the company’s sales, actually seemed to be buying more Contessa rum from rival Radico Khaitan, than Old Monk.

Also, unlike United Spirits who made McDowell’s (and which was taken over by Diageo in 2013-2014), Mohan Meakin adamantly refused to countenance any strategic partnership, let alone a sale, though it had been approached for its beer business by both Budweiser and Carlsberg, and even scuttled talks of a takeover by SABMiller in 2006 by insisting any lease (and not an outright sale) be for ten years, which of course was as good as saying “not interested”. The fact that some 66% of equity was held by the family in 2012 surely made such decisions easier, but no less problematic or short-sighted in the absence of a clear plan for revitalizing the firm’s fortunes. It comes as no surprise that even loyal employees of the company sniffed disparagingly in 2016 that the management was a bunch of old farts (at the time some members of the board were well into their eighties) out of touch with a much different and fast-moving world where predators were always circling and there was no longer any insulation from foreign competition such as had permitted their initial growth.

Brigadier Kapil Mohan retired in 2015 due to ill health (he kept on contributing in a consulting capacity), and the reins were passed to a new generation, the third, exemplified by Vinay and Hemant Mohan, his nephews. They learned from the beginning of their employment with the company in the early 1990s that they had to start at the bottom and learn each part of the large and complex organization they might one day manage.

Left to Right: Hemant Mohan, Brigadier Kapil Mohan, Vinay Mohan (c 2000s)

Hemant took over as Managing Director of the company (he has been working in MM since 1991), and tried to address the enormous problems he had inherited, with Vinay on the board as a director lending support. In 2015 MM began to issue a premium variety of Old Monk (this was either the 12 YO in the bottle shaped like a figurine, or perhaps the Legend) with some success, but in a cost cutting move that annoyed many loyal buyers who prized their personal relationships with the company’s sales representatives, they outsourced distribution to a third party who had no such feel for old and valued clients. However, that aside, there were signs of improvement: new product launches, rebranding, more aggressive marketing, a drive to premiumisation with Old Monk Gold Reserve, Old Monk Supreme and some limited edition bottlings – all these helped bolster sales to more than five million cases in 2017 after touching an all-time low of 3.5 million cases just a few years prior.

By the mid-teens the company had settled some of the earlier issues referred to above and in a 2016 interview, Vinay Mohan said that loss making entities like the glass factory had been shut down, Tamil Nadu had been “sorted” and markets in Bengal and Maharashtra were showing good growth. He dismissed any notions of the company going under or Old Monk being discontinued or sold, and glossed over distribution problems that continued to plague the company; and in the following years the company put out many statements where they flatly said they would never discontinue Old Monk unless the entire company went belly-up. Well, okay. Certainly some of the cost cutting had its intended effect, for while operating income grew sluggishly in the three years to 2017, net profit doubled and debt declined 40%. Whether the “Ready to drink” flavoured range of underproof cocktail rums released in 2018 (and other such marketing strategies) was successful and can arrest the long term issues the company faces is yet to be seen.

The future is cautiously optimistic, and only time will tell whether they can weather the storm. They are fighting a battle on many fronts: aggressive competition from huge multinational spirits conglomerates boasting many renowned brands of their own; first-mover advantages they squandered by the many missed opportunities foregone as the markets opened; increased drive to premiumization and an ever-more-crowded marketplace for really good rums, in which Old Monk is not regarded as a top tier product by anyone outside India and served to a population that has been blinded by the elegance-factor of high end whiskies.

The Old Monk Line (not complete)

On the flip side, Old Monk is an international brand and does have devoted fans — one such formed a group called COMRADE (the Council of Old Monk Rum Addicted Drinkers and Eccentrics); also, the widely scattered diaspora remembers it fondly, and the army continues to be a supporter – but the new generation of company management intends to expand beyond these notions of half-remembered and faded old glory. They want to recapture their lost market share by targeting different audiences (primarily young adults and the new middle class), with more limited edition releases, different blends and even tap into the ready-to-drink “instant cocktails,” flavoured editions and infused white rums – and that extends beyond rum, and to their whisky and vodka brands as well.

If they can diversify into more export markets while retaining those markets they already have, expand into other price point products and fix their distribution problems within Asia generally and India in particular, then it’s likely they will do just fine. And then India will continue to be represented well in the category, perhaps by a rum that won’t be just another vanilla-infused has-been from decades ago, but a true and pure rum that will take its place with all the other good ones so many people from around the world are enjoying right now.

Brief Timeline of the Company

- 1855 Dyer’s is registered as a limited liability company

- 1884 Dyer’s Murree Brewery of Punjab acquires Ceylon Brewery

- 1887 Meakin Breweries bought Solan and Kasauli operations from Dyer

- 1920s Joint Venture with Dyer and Meakin’s operations

- 1937 Full merger of both businesses to form Dyer Meakin Breweries Ltd.

- 1949 – Narendra Nath Mohan takes control of Mohan Meakin

- 1954 Colonel Ved Rattan Mohan (1928-1973) creates the Old Monk brand with his father

- 1966 Dyer Meakin renamed Mohan Meakin

- 1967 Mysore Fruit Products becomes a subsidiary

- 1969 VR Mohan takes over Mohan Meakin

- 1973 Brigadier Kapil Mohan (VR’s younger brother)takes over MM after VR dies.

- 1975 Glass factory opened in Fiji

- 1978 Another distillery opened in Bhutan

- 1980 Company name changes to Mohan Meakin Ltd. Experiments with carbonated sodas

- 1982 Expansion into the USA

- 1983 Brewery set up in Chennai

- 1986 Decline in profits as energy prices rise

- 1990 Hemant Mohan joins company (son of Sukhdev Mohanr)

- 1994 Vinay Mohan joins company (son of Sukhdev Mohan)

- 1995 Highland Queen and Grand Reserve whisky brands launched

- 2015 Hemant Mohan takes over as MD as Brigadier retires for health reasons

- 2018 Brigadier Mohan dies at 88 (reported 6 Jan 2018). Hemant Mohan becomes CEO

- 2018 “Ready to drink” range debuts on the market, released to arrest the slide of sales

Other Notes

- Some sources, including wikipedia, say Edward Dyer was in India from as far back as the 1820s but this conflicts with more formal published accounts which say he returned in 1850. The date of the first brewing and distilling operation is similarly problematic, some saying 1850 or so, others saying a generation earlier. The stories can be somewhat reconciled if we accept that Dyer’s father or someone known to him was the man who set up that first brewery which failed in 1840, and then Edward Dyer, armed with that knowledge, came back with modern equipment in 1850 to begin the new distillery and brewery. This article is the only one I’ve seen suggesting such an interpretation but it in turn conflicts with other accounts which give Dyer’s date of birth as 1831.

- Still, I believe that wikipedia is in error here: it states Dyer and Meakin merged in 1835 and this is inconsistent with too many other sources. Edward Dyer had to be at least 30 in 1835 under this interpretation, so assuming he was born in 1805 or so, this would make him 60 years old, give or take, when his son Reginald was born in 1864. I find this unlikely.

- There is a story that Rocky Mohan (Ved Rattan Mohan’s son), who is retired from the company, sold the Lucknow distillery to Ponty Chada, the man who engineered the monopoly for Wave Distilleries in Uttar Pradesh in 2009, but this is not reported elsewhere.

Sources

- Kasauli Brewery early history (see photos for attribution information). As stated above, I have issues with the dating of this article.

- Early Dyer history from The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginal Dyer (2005) by Nigel Collet Chapter 1. Additional notes on ancestry and family tree from The Life of General Dyer (2006) by Ian Colvin, Chapter 1.

- Notes on General Dyer, social circumstances and racism in British India

- Meakin history as brewers mentioned in wikipedia, the 1726 London Gazette, and Lewis Meakin’s expansion by taking over the Abbey Brewery in 1822, as well as Charrington Brewery which took over Meakin’s in 1872. Also here. Burton-Upon-Trent photo taken from this brewery history, p.49

- Mohan family history (less interesting precis from Economic Times India here)

- India’s New Capitalists: Caste, Business, and Industry in a Modern Nation (2008) by Harish Damodaran page 73 and 74

- Brief historical overview of Mohan Meakin. Notes on initial expansion and background to name change in 1966.

- Initial issue of Old Monk in 1954.

- Competitors and other liquor companies in India

- Timeline of some key financial events of the company (to 1995)

- Company website and wikipedia. Background wiki on Old Monk and VR Mohan

- Poor strategy in 2012 and no advertising rule. Decline in 2000s and competitors

- Cult of Old Monk article

- 2018 article showing decline of Old Monk (graph) and Kapil Mohan’s passing

- Future plans after Kapil Mohan, with nephews Hemant and Vinay Mohan

- Company Annual report 2018-2019

- Rumporter magazine article “A Brief History of Rum in India.”

- Obituary of Kapil Mohan and notes on his legacy

- FB video on Old Monk history in summary

I don’t know why Mohan Meiken share price is not Rs.5000/-.

The today’s cost of installing such a plant with land and building cost is very very high.

Why people are not pricing that.

It’s a future Diamond. Must invest in this company.

Herery George Meakin was the eldest son of Henry James Meakin and grandson of Lewis Meakin. There is no mystery here. It is well documented. Although only distant relations also in India at the same time was Edward Ebernezer Meakin who we think due to his association to H G Meakin his son had a book sponsered by Lewis Meakin.

It would be useful if you could point me to where exactly this information can be found, since while it may be “well documented” it is certainly not easily located. I’ve updated the post for the little bit you’ve provided.

I will come back to you on this. I have the full tree for the pottery Meakin family which includes the Burton on Trent brewers and will see if I can find an accurate tree on ancestry.com. The tree I have was researched by Peter Platt and was given to me about 1999. Peter also had wills for Lewis Meakin but I dont have access to those but he was very thorough in his research and helped me considerably with my own tree. I dont think he ever published this online.

Here is the available genealogy on ancestry.com Lewis Meakin Brewer of Burton on Trent Probate 9 Dec 1842 mentions his son Henry James Meakin and also appointed him one of the executors of his will Henry James Meakin was baptised in Burton on Trent 21 Aug 1816 and his parents listed as Lewis Meakin and Elizabeth. Henry George Meakin was the son of Henry James Meakin and Ann Bagnall and although I cant find a baptism for him he is shown as the son of Henry James Meakin as a 17 year old in the 1861 census. There is a will for henry James Meakin but I can access the content but Peter Platt would have obtained that will. There is also a probate for Henry George Meakin in India but it did not add much to the story. I hope this helps.

Company give the material for marketing?

If they had, I would have mentioned it in the sources. So the answer to your question is no.