In less than a decade, the indigenous spirits of Haiti have gone from being local moonshine known only to locals, residents of the DR, visiting NGOs, Haitians in the diaspora and the occasional tourist, to rhums that have made their mark and become famous the world over. They are enormously complex, traditionally made, un-tinkered with and unaged, and have helped usher in an appreciation for artisanal cane spirits that would have been unthinkable to the aged-rum establishment as little as ten years ago.

The rums, with their fierce and fiery tastes, initially appealed mostly to cocktail makers (and drinkers), which is to say, barkeeps and barflies, and rum aficionados who know this stuff backwards and forwards. But their immense and uncompromising profiles are gradually finding a more general audience elsewhere as well: the great mass of rum drinkers who are more middle-of-the-road, who inhabit the medium-to-low price range and are at best occasional tipplers of more exotic fare like this. Slowly but surely, the clairins are winning them over.

Of course, it could be argued that a much more approachable and well-known Haitian rum brand is Barbancourt, and indeed, one of their range has already been inducted to the Key Rums pantheon. But while the clear style of the Barbancourt rums is worthy of being the first entry into the series from Haiti, one cannot seriously discuss the rums of the half-island without also acknowledging its long-made artisanal backcountry rums. They may be occasionally divisive, perhaps even an acquired taste, yet for those who take a deep breath and dive right in, they are amazingly flavourful, complex and versatile rums. Nobody who claims they love the category can pass them by, or walk away unaffected by their uncompromisingly wild and untamed natures.

For the purposes of this entry, I am limiting the clairins to the five unaged white rums distributed and popularised by the Genoese firm of Velier, not any of the aged variants that have became available as the years progressed, or any of the blends – they all take second place in my estimation to the unaged versions, and I argue that when it comes down to it, it’s the five from Velier that form the base upon which our knowledge of the others rests. You could say they are the core clairins of our comprehension of the subcategory and serve as useful stand-ins for all the others.

As a straightforward and simple introduction, clairins are unaged cane juice (or sugar cane syrup) rhums made in Haiti, usually by small village distillers using cane from small nearby fields (often their own), crushing it with primitive machinery, fermenting with wild yeast, and running the wash through bare-bones and rudimentary (occasionally home-made) distillation equipment – pot stills, for the most part. Bottling is haphazard and it’s not unheard of for people to bring their own containers to the tiny distilleries to fill up, and the result is sold as-is, almost exclusively at the local level. Much is also sold to village pharmacies in 55 gallon plastic drums and they bottle it for the final consumers. And it’s long been a practice for merchant bottlers in the neighbouring Dominican Republic to buy clairins in bulk and use it to give their own softer rons some kick and flavour (or to release their own “branded” clairins which are then retailed in both countries). Many larger distilleries do this and rarely or never bottle their own work.

Clairins, then, inhabit a sort of strange universe: they are indigenous, small batch, local spirits and one of their initial selling points to the western world was that they were made on small pot stills, adhering to very old and little-changed methods of distillation dating back to the very introduction of nascent distillation technology by the French plantocracy, more than two centuries ago. The little producers didn’t care if they got a wider distribution in the region, let alone the world, and remained an enclave of spirit making frozen in time. Unsurprisingly, this was a Thing for those of the new rum generation who sought out “natural” and “genuine” spirits that did not interact overmuch with something like, oh, modern technology.

While there are many scores of small clairin makers scattered around Haiti (500 or so, is a statistic often bruited around1), they remain primarily rural spirits like charandas in Mexico or grogues in Cabo Verde or aguardientes everywhere else (in fact, a case could be made that they are aguardientes in all but name).

As he recounts in his book Nomade tra i barrili (“Nomad among the barrels”), Luca Gargano went to Haiti in 2012 to meet Herbert Linge and Jane Barbancourt and took the time to go around the countryside, where he started to come across these local small distilleries. He tried some of their products and was completely enthralled with the natural, strong tastes they displayed. Unsurprisingly the first he sampled was one Michel Sajous made down in Chelo (the gent was already very well known in Haiti for his clairins), and a casual offhanded remark a few days later pointed Luca to Fritz Casimir over in Vaval; and some time after that, a chance meeting on the road led to Duncan Casimir’s place (now run by his son Faubert).

As he recounts in his book Nomade tra i barrili (“Nomad among the barrels”), Luca Gargano went to Haiti in 2012 to meet Herbert Linge and Jane Barbancourt and took the time to go around the countryside, where he started to come across these local small distilleries. He tried some of their products and was completely enthralled with the natural, strong tastes they displayed. Unsurprisingly the first he sampled was one Michel Sajous made down in Chelo (the gent was already very well known in Haiti for his clairins), and a casual offhanded remark a few days later pointed Luca to Fritz Casimir over in Vaval; and some time after that, a chance meeting on the road led to Duncan Casimir’s place (now run by his son Faubert).

These three small distilleries, out of all the others, formed the initial export crop of the clairins which were to become so well known in the years that followed. By 2014 they were on sale in Europe and Velier lost no time promoting the hell out of them. They brought bartenders to Haiti to demonstrate the country and the rhums; created the Clairin World Championship; brought out new expressions every year; started ageing some into the Ancyen line of aged clairins; blended them into various permutations, such as the Communal; and added two new mainstays from Le Rocher and Sonson by 2019 in an ongoing effort to expand the range.

The impact these rums had is undeniable and this is where it is useful to keep in mind how fast the rumworld is moving. Even in 2014 when limited-edition aged rums from independent bottlers were becoming more famous and more sought after, the market was still mostly about producers’ brand stables of progressively more aged rums (gold, anejo, vieux, 5YO and up, etc) and filtered cocktail whites like Bacardi’s Superior or various Latin Blancos. Agricoles were a small but growing niche market, with aged agricoles being considered the ones to get, and outside of the enthusiast’s sphere of interest, “real” white rums from the French islands were relegated mostly to those islands, or metropolitan France. “Unaged” was not seen as a selling point, Rum Fire and Rumbar rums were not a thing, and the Wray & Nephew white overproof was too often dismissively shrugged off as a “Jamaican diaspora rum” or relegated to the tourist trade, not seen for the classic it later came to be.

The impact these rums had is undeniable and this is where it is useful to keep in mind how fast the rumworld is moving. Even in 2014 when limited-edition aged rums from independent bottlers were becoming more famous and more sought after, the market was still mostly about producers’ brand stables of progressively more aged rums (gold, anejo, vieux, 5YO and up, etc) and filtered cocktail whites like Bacardi’s Superior or various Latin Blancos. Agricoles were a small but growing niche market, with aged agricoles being considered the ones to get, and outside of the enthusiast’s sphere of interest, “real” white rums from the French islands were relegated mostly to those islands, or metropolitan France. “Unaged” was not seen as a selling point, Rum Fire and Rumbar rums were not a thing, and the Wray & Nephew white overproof was too often dismissively shrugged off as a “Jamaican diaspora rum” or relegated to the tourist trade, not seen for the classic it later came to be.

The release of the first three clairins and the subsequent marketing and bartender involvement, gave the entire category of unaged, unfiltered, natural white rums an enormous boost in visibility, helped even more by social media and the first crop of reviewers who championed them. In the years that followed, agricole rhum makers from Reunion, Guadeloupe, Marie Galante and Martinique — among others — expanded their ranges of white rums, issued others at new proof points (mostly stronger) and even began a few annual releases here and there…the line from clairins’ success is an indirect one to be sure, but another emergent trend, that of parcellaire rhums, can owe at least a small influence to the terroire so clearly associated with each of these so-very-different Haitian whites.

The increasing visibility (and sales) of the clairins was at a minimum a contributing factor in allowing new micro-distilleries to take the chance of issuing unaged white rums of their own: the Asia-Pacific rumisphere of new brands like Issan, Chalong Bay, Mia, Naga, and Sampan may have co-existed or even predated the clairins, but I argue that they were more locally sold than exported, and the clairin tide was certainly one that helped lift their boats on the international scene as well. Aguardientes, grogues, charandas, arrack, kokuto shochu, Vietnamese rượu and many other such cane spirits which are gaining in popularity are in some small part indebted to the respect accorded to unaged cane juice rums so exemplified by the clairins.

As recently as April 2022, Malt’s writer Han, in a retrospective on the class, suggested that the lack of acceptance of these clairins in the stable Velier’s distributed rums — as opposed to the mania surrounding the Demeraras and Caronis (all of which were aged rums) — resulted from the rhums’ peculiar inability to be neatly pigeonholed and classified, and therefore they were not considered must-haves and financial money-spinners the way the others were. That may once have been so, back when unaged white cane spirits were unusual and considered too lowbrow for wide acceptance. That’s now changing – and indeed, Han resolutely recommends that people give these rums a closer look and maybe a re-taste to see how really good they are. What were once seen as puzzling differences inhibiting neat placement, are increasingly considered sought-after terroire-driven individual characteristics, demonstrating that the the international rhum audience is learning, adapting, accepting and growing. The clairins are going mainstream, big time.

As recently as April 2022, Malt’s writer Han, in a retrospective on the class, suggested that the lack of acceptance of these clairins in the stable Velier’s distributed rums — as opposed to the mania surrounding the Demeraras and Caronis (all of which were aged rums) — resulted from the rhums’ peculiar inability to be neatly pigeonholed and classified, and therefore they were not considered must-haves and financial money-spinners the way the others were. That may once have been so, back when unaged white cane spirits were unusual and considered too lowbrow for wide acceptance. That’s now changing – and indeed, Han resolutely recommends that people give these rums a closer look and maybe a re-taste to see how really good they are. What were once seen as puzzling differences inhibiting neat placement, are increasingly considered sought-after terroire-driven individual characteristics, demonstrating that the the international rhum audience is learning, adapting, accepting and growing. The clairins are going mainstream, big time.

In short, the five clairins which form the backbone of the exported Haitian artisanal rhum ecosystem – no matter from which year – are serious Key Rums, and no one can be addressed without mentioning every other. They remain affordable, they are originals by any standard, and have become regular bartenders’ backbar staples. They shine in cocktails, yet they can, for those willing to take the chance, be worth trying neat as well, because in few other spirits is the origin, the terroire, the entire process of making it, so evident as in one of these rhums. Their introduction channelled long-gestating trends already gathering a head of steam and perhaps coasted on their coattails rather than creating anything singular themselves – however, I also suggest that they enlarged and accelerated those same trends and had an influence on all rums of this type that came afterwards. They are important rhums from Haiti that need not be overshadowed by Barbancourt, other agricoles, or cane juice distillates made elsewhere, and can co-exist very nicely alongside them all as unique and flavourful rums of versatility and individuality in their own right.

The Rums as of 2022

The very brief tasting notes represent a (December 2021) re-tasting of those bottles I bought and reviewed over a period of some years. Since there’s a new version out every year or so, the ones I mention below are to be considered as representative only, and the reader should be aware of variations over the years, and from their own experience. However, I do believe that they provide a sense of the differences among them all, their similarities, and something of why they remain so enthralling.

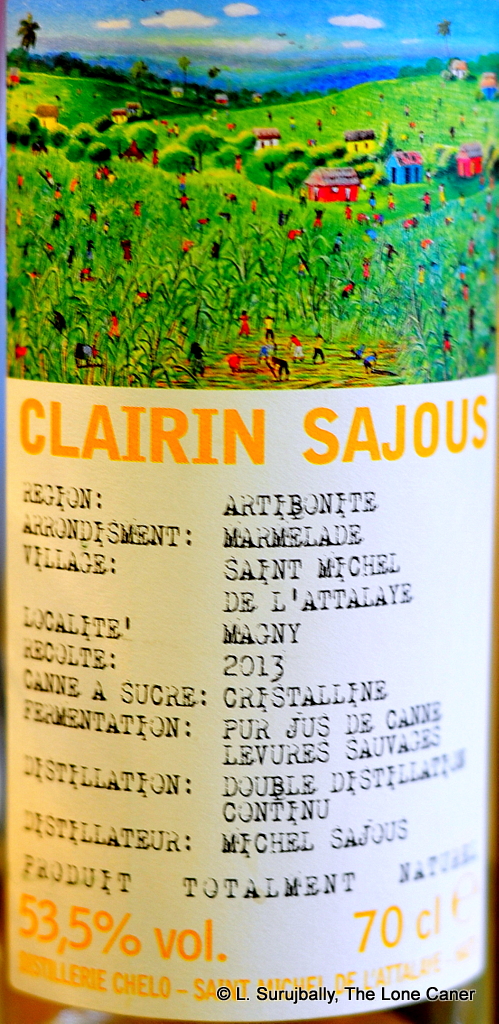

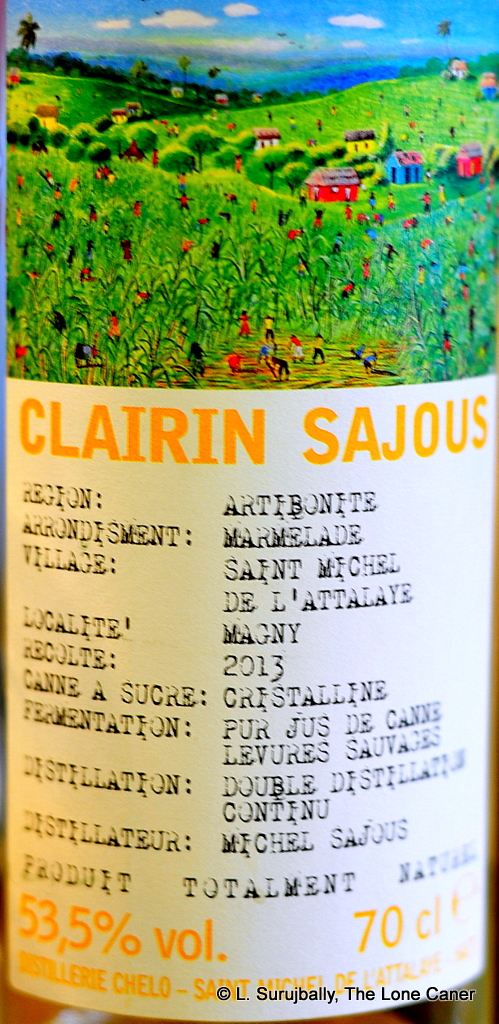

Clairin Sajous 2013 Release, 53.5%

Clairin Sajous 2013 Release, 53.5%

The first clairin I ever tried, the most shocking and still, to me, the fiercest, most rambunctious and fearless – and I feel that way about it perhaps because I came upon it so unexpectedly, without warning, and it knocked me flat. The huge nose reeked of wax, brine and gunpowder, fusel oils and lacquer, sugar water and salt beef, and the taste, solid and savage at the same time, channelled cane sap, brine, olives, unripe fruit and balsamic vinegar. Even at 53.5% it retained seriously savage character that I’ve spent a lot of time and retatstings coming to grips with.

Clairin Casimir, 2013 Release, 54%

Clairin Casimir, 2013 Release, 54%

Of all the clairins I’ve tried, this remains my favourite, “maddening and strange if you are not in tune with it, mesmerising if you are.” Floor polish, turpentine, kero on the nose, plus sugar cane juice, sweet soya sauce and salty vegetable soup, plus sultry, dark overripe fruits. Palate wise it’s so well done – thick, voluptuous, herbal, citrus, spicy and even sushi-like, just fruity and sweet enough to be really enjoyable. I still believe it’s the most elegant of the lot, though I’m aware that others have their own favourites in the line.

Clairin Vaval 2013 Release 52.5%

Clairin Vaval 2013 Release 52.5%

Also a very good initial foray into the world of clairins, the Vaval is the third of the first edition of clairins released by Velier, and sports a more restrained but still Sajous-like nose of petrol-wax-brine explosive oomph, plus some vanilla, sugar water, unripe strawberries and tart pineapples. The taste is almost civilised: grass, herbas and an overwhelming sense of a vegetable garden next to freshly cut grass in the sun after a rain. It has spices, herbs, sugar cane sap and vanilla, and is a completely decent intro to the class.

Clairin Le Rocher 2017 Release, 46.5%

Clairin Le Rocher 2017 Release, 46.5%

The fourth addition to the pantheon, Le Rocher is much more civilised than the first trio: it’s 46.5% and made from cane syrup, not juice. It smells of salt, soya and soup, and also of light, crisp herbals and fruits. Plus some carrots and a flower or three. It tastes light and even warm, quite easy warm weather drink, though it retains much of its primitive antecedents: bitter chocolate, wax, cane sap, herbs, olives, and perhaps iodine and wet campfire ashes. Well, nobody said it was easy, not even me. I liked it, though.

Clairin Sonson 2018 Release 53.2%

Clairin Sonson 2018 Release 53.2%

Made in 2018, ready for distribution in 2019 and then hit with delays relating to the worldwide COVID shutdown, it wasn’t until 2021 I managed to buy the fifth clairin. Like Le Rocher, it’s made from cane syrup, not juice, but when nosed, it feels like an only slightly restrained Sajous is trying to get off the leash – fuel, brine, wax, plus acetones, paint, cider and some oddly variegated fruits – bananas, gooseberries, green apples. A sweet, pungent, tart citrus-y melange combines on a rather luscious palate, and the whole thing is best taken at leisure over a period of time allowing it to open and reveal its true nature…which isn’t bad at all.

Other notes

- There as yet is no official or regulated criterion for what constitutes a clairin. Velier came up with a series of protocols to define them, but these are somewhat contentious, and not widely accepted – not even within Haiti. This is one of those areas where the Haitian Government or the local producers should really try for a PDO or GI or some form of regulation, just to nail the term down more precisely and ensure minimum standards of production and quality control.

- Luca Gargano, the CEO of Velier has always made it clear that none of the rums he distributes are “his” or “Velier’s” (Providence and Rhum Rhum brands excepted) – they are, front and centre, rums from the distillery and the location that are marked on the label and the box. I call them “Velier’s Clairins” here for clarity and to avoid the inevitable question of “what about all the others?” had I left Velier’s name out.

- A very good listing of all Velier’s iterations of the various clairins can be found on Spirit Academy.

- For now, I can’t quite make a case for inclusion of the only other clairin that is reasonably well known – Saint Benevolence – because for all its laudable charity work and exposure in the States and Britain, it remains relatively low key and uncommented on elsewhere, and lacks wide distribution outside those countries. This applies even more to other kleren / clairin makers in Haiti, like Lacrete, Beauvoire Leriche, Barik / Moscoso, Janel Menard, Cap Haitien / Nazon, Distillerie de la Rue, Agriterra Cotard or Agriterra Himbert. These sell mostly within Haiti itself, or vanishingly small quantities abroad – many just sell bulk, and they have rarely been tried by most (including me). I hope to change that in the years to come, as there’s always space in the list for more.

- An excellent retrospective on clairins was Han’s, who posted first on Malt and a few day’s later re-posted on 88 Bamboo (both in April 2022). It’s one of those coincidences of nearly-concurrent publishing that crops up from time to time.

- Hat tip to Han of 88 Bamboo for permission to quote from his article and use any photo I wished, and my deepest appreciation to Chris Francke and John Go, who took those great pictures of their own of the entire range of core clairins, and allowed me to re-post their work here. Thanks, all of you.