The practise of wine and spirits merchants releasing their own branded products is a long and storied one, going back more than a century (think of Berry Bros. and Rudd, Doorly’s, Goslings, or even Masters of Malt, as just a few examples). They acted, therefore, as progenitors and continuations of the indie bottling scene that has so defined the upscale market in the modern rumiverse.

The practise of wine and spirits merchants releasing their own branded products is a long and storied one, going back more than a century (think of Berry Bros. and Rudd, Doorly’s, Goslings, or even Masters of Malt, as just a few examples). They acted, therefore, as progenitors and continuations of the indie bottling scene that has so defined the upscale market in the modern rumiverse.

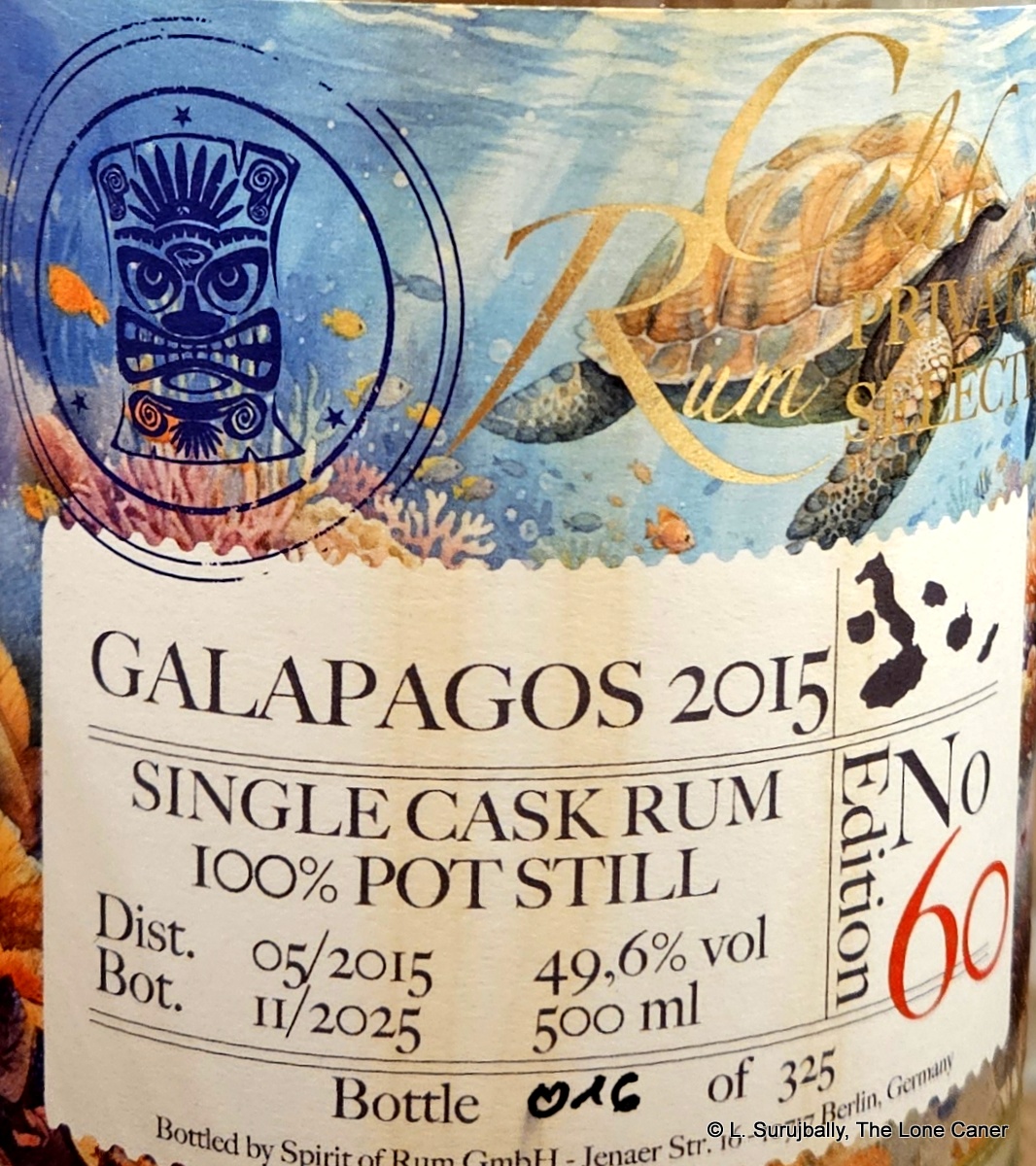

One of the best of such shops in Germany is undoubtedly Dirk Becker’s Rum Depot in Berlin, which I have been visiting on and off since 2012 and remains a favourite stopping place of mine. That same year, they began releasing single cask bottlings under their own brand called Rum Club Private Selection, and have steadily added to the stable until they just arrived at #60 in 2025, with this highly unusual bottling from – and yes, it really is – the Galapagos Islands in the Pacific Ocean, and I’ve provided a bit more in-depth background below the review for those who are interested and asking wtf? (as I did).

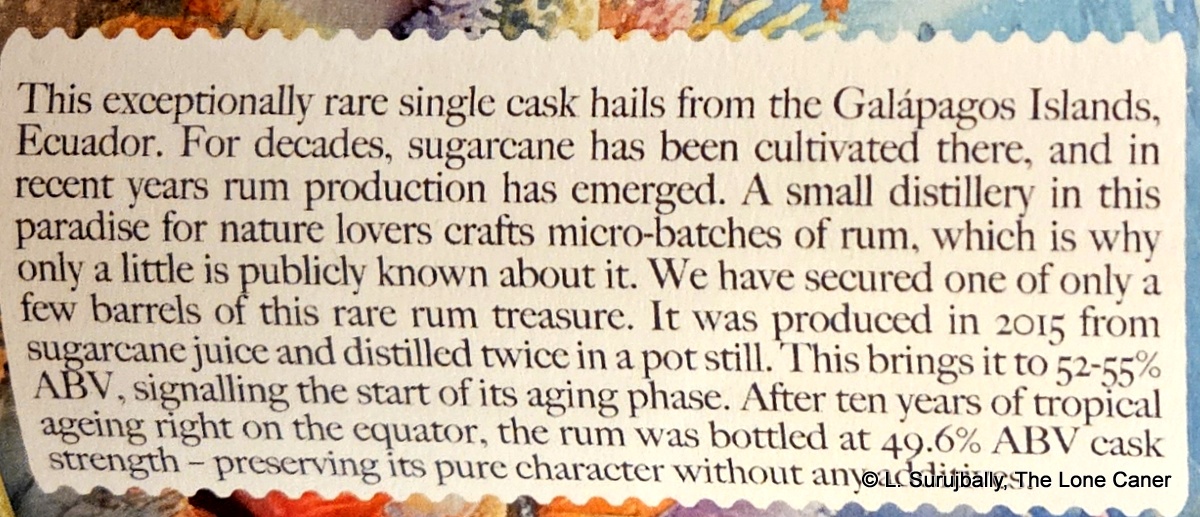

Stats: distilled in 2015 from sugar cane juice and double distilled in a pot still (it may actually be a trapiche), then set to age in situ for ten years — the barrels are not mentioned, though we can reasonably assume ex-bourbon. How precisely it got into Rum Depot’s stocks – whether a direct purchase on the island or via a broker as part of a batch, is unknown. The label makes mention of “one of a few barrels” which makes it unlikely to be a bulk sale (e.g. an iso-container that was later decanted), but whatever the case, the rum came from one barrel, and has an outturn of 325 bottles, at a solid 49.6%.

What I liked about it right off the bat is that it had that vaguely rough vibe of an artisanal back-country rum that’s not quite smoothened out by decades of commercial manufacturing experience. It immediately gave off fumes of dialled-down Jamaican funkiness – orange rind, overripe pineapples, gooseberries, pickled cabbage, glue and plastic – and here I think the middling strength worked well to tamp it down. It also presented vanilla, cinnamon, cardamom, a slight musky sweetness, like Indian kheer, leavened with the faint bitterness of black chocolate. And here I must point out that that the crisp vegetal tang of a true agricole really wasn’t very noticeable, which is somewhat surprising.

What I liked about it right off the bat is that it had that vaguely rough vibe of an artisanal back-country rum that’s not quite smoothened out by decades of commercial manufacturing experience. It immediately gave off fumes of dialled-down Jamaican funkiness – orange rind, overripe pineapples, gooseberries, pickled cabbage, glue and plastic – and here I think the middling strength worked well to tamp it down. It also presented vanilla, cinnamon, cardamom, a slight musky sweetness, like Indian kheer, leavened with the faint bitterness of black chocolate. And here I must point out that that the crisp vegetal tang of a true agricole really wasn’t very noticeable, which is somewhat surprising.

Tasting it confirmed that impression. It landed nice and firm, no sharp scratchiness here. Immediate notes of light citrus, soda-pop (say, 7-Up), cola, vanilla and the sour hint of both overripe fruits (gooseberries and pineapple and mango) and pickled cabbage. Once it opens up you can detect some brininess, tartness, funkiness, dark cherries, and a touch of honey. Not as complex as the nose suggests, yet it quietly shines in its own way, and if the finish is a little spicy and goes away too fast – final notes of caramel, vanilla, cinnamon, unsweetened chocolate again, light citrus and kefir – it’s by no means a slouch.

So what did I think? Well, I’m a bit conflicted. Strictly speaking, this is an agricole style rum (off a pot still, no less), yet much of the grassy and herbal profile of rhums from Reunion or the Caribbean French Islands, is mostly AWOL. One would be hard pressed to call it for what it was if tasted blind, and this reinforces my belief that there is a diminishing return on cane juice rums once they are aged past a certain point, after which the barrel influence is simply too pervasive and the terroire and originality starts to go.

Taken on its own terms, it’s pretty good, though. The strength is solid, the tastes are a lovely amalgam of salt and sweet and sour with just a bit of green funk thrown in for good measure — and if perhaps the terroire is not as clear as we might like, everything else is really well integrated into the alcohol and the overall texture and mouthfeel. It’s like a cross between a lightly-aged Jamaican, a young Guyanese without the lumber, and, yes, if one reaches, some sweet cane juice rhum notes too. For €65 or so, there is no reason not to get it, not least because… well, come on, the Galapagos? Who else can lay claim to having something from there, right? It’s unusual and has great production specs, from a place we know little about, and is a damned enjoyable drink. Taking that into consideration, I’d suggest that if you can, and if Dirk hasn’t sold out yet, go get yourself a bottle.

(#1136)(85/100) ⭐⭐⭐½

Other notes

- Video review link

- There aren’t many reviews out there for the rum – most of what I see is quick notes left on Rum-X or online stores. I guess that the limited release and its specialized nature make it more likely to appeal to collectors or serious geeks (or certifiable reviewers).

- Given the ecological status of the islands, and since they are protected as part of Ecuador’s Galápagos National Park and Marine Reserve, it’s reasonable to ask – is there really a distillery there, or is it from Ecuador, of which the islands are a province? Well – yes. There is a outfit called El Trapiche Ecologico Galapagos, which is a tiny family-run artisanal farm and distillery located in the highlands of Santa Cruz Island, and is a popular tourist destination. But it seems to be more an organic operation that grows coffee, cocoa and sugar cane and does some distillation on the side. It was once known as Darwin’s Lab, Dirk told me, and research suggests it is now more involved with environmental and ecological matters than distillation proper. What is interesting about it is that Johan Romero, who does run a full fledged family-owned distillery in Quito (many independent bottlers’ Ecuadorean rums come from here), helped build that trapiche and advised on cane, fermentation and distillation.

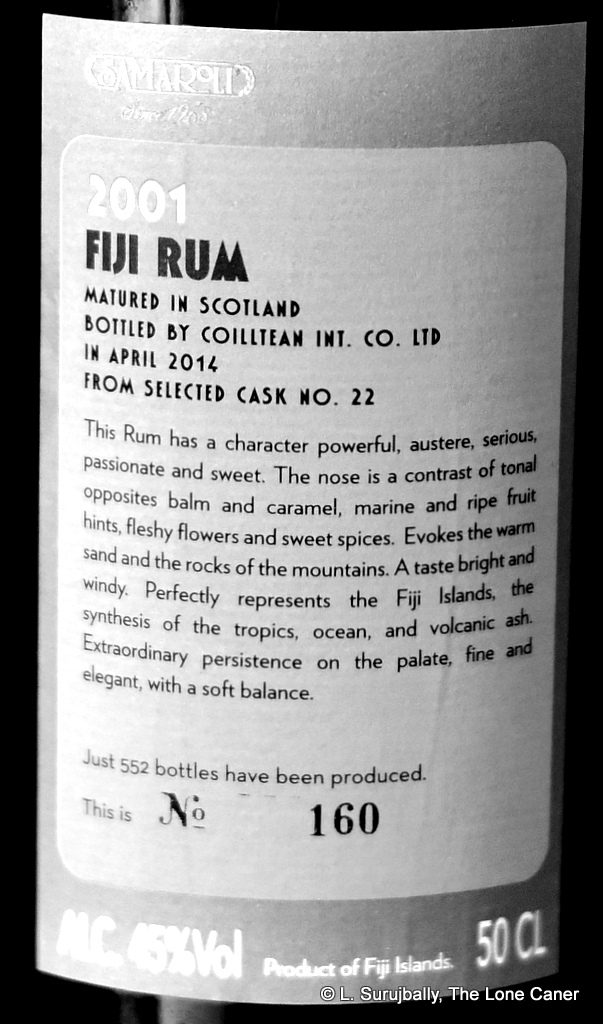

It was obvious after one tiny sniff, that not one percentage point of all that proofage was wasted and it was all hanging out there: approaching with caution was therefore recommended. I felt like I was inhaling a genetically enhanced rum worked over by a team of uber-geek scientists working in a buried government lab somewhere, who had evidently seen King Kong one too many times. I mean, okay, it wasn’t on par with the

It was obvious after one tiny sniff, that not one percentage point of all that proofage was wasted and it was all hanging out there: approaching with caution was therefore recommended. I felt like I was inhaling a genetically enhanced rum worked over by a team of uber-geek scientists working in a buried government lab somewhere, who had evidently seen King Kong one too many times. I mean, okay, it wasn’t on par with the

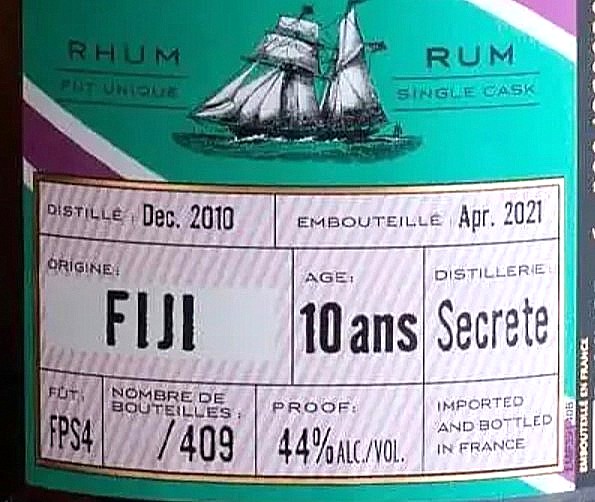

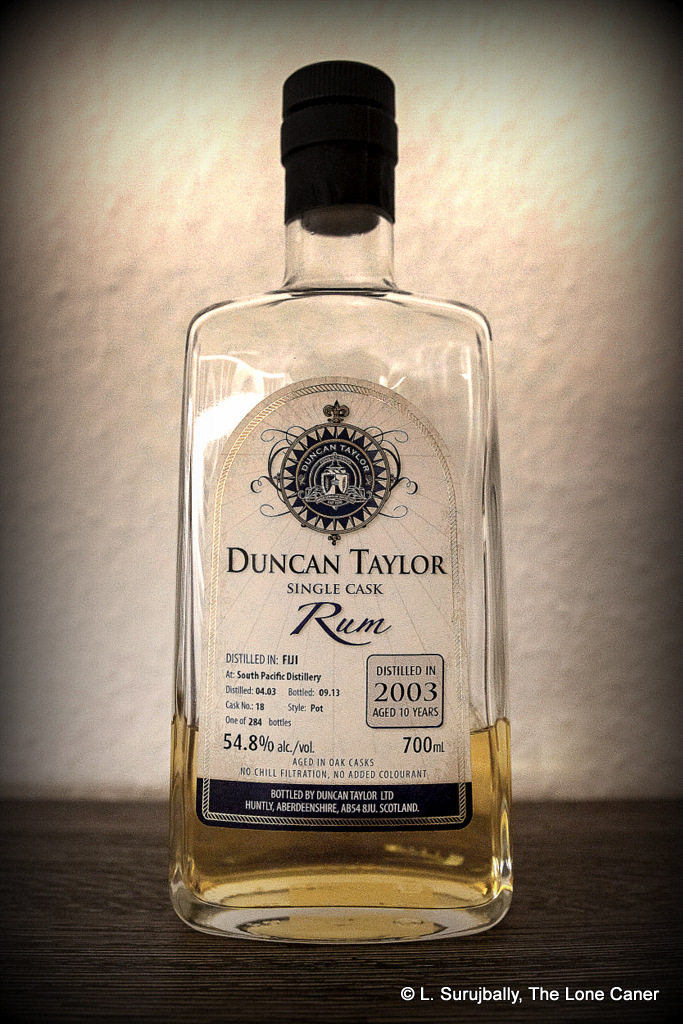

That said, the still which produced this pale yellow 57.19% ABV rum remains an open question, though my personal belief is that it’s a column still product. It certainly noses that way – aside from presenting as a fierce little young rum, it lacks something of the depth and pungency of a pot still spirit. However, that doesn’t matter, because it’s damn fine on its own merits – brine, olives, paint, turpentine, acetones, fresh nail polish, more brine and gherkins, and that’s just the beginning. It has aspects that are almost Jamaican, what with a bunch of prancing dancing esters jostling for attention, except that the smell is not so crisply sweet. It develops very nicely into smoke, leather, linseed oil for cricket bats, more brine and oily smoothness. Like a set of seething rapids finished with the messing around, it settles down to a much more refined state after half an hour or so.

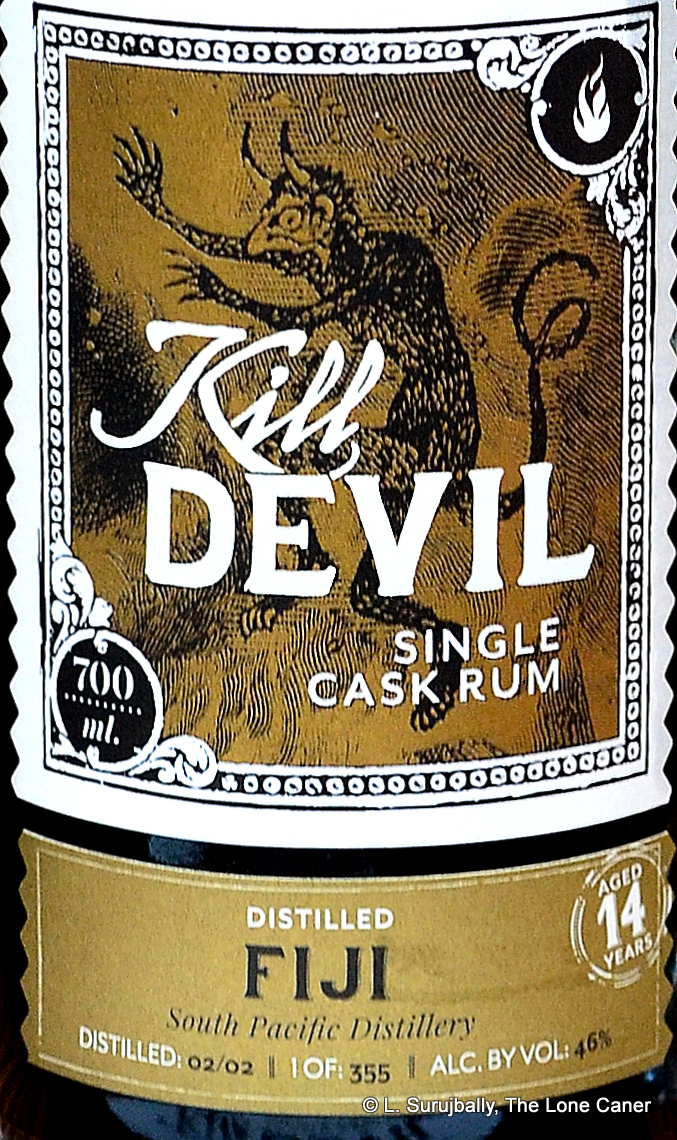

That said, the still which produced this pale yellow 57.19% ABV rum remains an open question, though my personal belief is that it’s a column still product. It certainly noses that way – aside from presenting as a fierce little young rum, it lacks something of the depth and pungency of a pot still spirit. However, that doesn’t matter, because it’s damn fine on its own merits – brine, olives, paint, turpentine, acetones, fresh nail polish, more brine and gherkins, and that’s just the beginning. It has aspects that are almost Jamaican, what with a bunch of prancing dancing esters jostling for attention, except that the smell is not so crisply sweet. It develops very nicely into smoke, leather, linseed oil for cricket bats, more brine and oily smoothness. Like a set of seething rapids finished with the messing around, it settles down to a much more refined state after half an hour or so. Kill Devil is the rum brand of the whiskey blender Hunter Laing, who’ve been around since 1949 when Frederick Laing founded a whisky blending company in Glasgow. In 2013 the company created an umbrella organization called Hunter Laing & Co, into which they folded all their various companies (like Edition Spirits and the Premier Bonding bottling company). The first rums they released to the market – with all the now-standard provisos like being unadulterated, unfiltered and 46% – arrived for consumers in 2016, which meant that this rum from the South Pacific Distillery on Fiji, was issued as part of their first batch (oddly, their own website provides no listing of their rums at all aside from boilerplate blurbs). When the time came for me to decide what to sample, the

Kill Devil is the rum brand of the whiskey blender Hunter Laing, who’ve been around since 1949 when Frederick Laing founded a whisky blending company in Glasgow. In 2013 the company created an umbrella organization called Hunter Laing & Co, into which they folded all their various companies (like Edition Spirits and the Premier Bonding bottling company). The first rums they released to the market – with all the now-standard provisos like being unadulterated, unfiltered and 46% – arrived for consumers in 2016, which meant that this rum from the South Pacific Distillery on Fiji, was issued as part of their first batch (oddly, their own website provides no listing of their rums at all aside from boilerplate blurbs). When the time came for me to decide what to sample, the  On the palate the fruits started to take over, tart and a unripe, like ginnips and soursop together with ripe mangoes, pineapple and cherries in syrup right out of a can – there was hardly any of the brininess from the nose carrying over, and as it developed, additional hints of pears, watermelon, honey, and pickled gherkins were clearly noticeable. It was warm and crisp at the same time, quite nice, and while the long and heated finish added nothing new to the whole experience, it didn’t lose any of the flavours either; and I was left thinking that while different from other Fijians for sure, it seemed to be channelling a sly note of Jamaican funk throughout, and that was far from unpleasant….though perhaps a bit at odds with the whole profile.

On the palate the fruits started to take over, tart and a unripe, like ginnips and soursop together with ripe mangoes, pineapple and cherries in syrup right out of a can – there was hardly any of the brininess from the nose carrying over, and as it developed, additional hints of pears, watermelon, honey, and pickled gherkins were clearly noticeable. It was warm and crisp at the same time, quite nice, and while the long and heated finish added nothing new to the whole experience, it didn’t lose any of the flavours either; and I was left thinking that while different from other Fijians for sure, it seemed to be channelling a sly note of Jamaican funk throughout, and that was far from unpleasant….though perhaps a bit at odds with the whole profile.

palled my enjoyment somewhat.

palled my enjoyment somewhat.