Moscoso Distillers (also known as Barik) is a third-generation Haitian rum-maker whose klerens caught my attention as I was researching rums from there that were specifically not Barbancourt or distributed by Velier. You’d think that some enterprising producers would extoll their family ancestry by tracing it back to Toussaint L’Ouverture’s great grandfather’s first cousin as part of the company legend, but as with many other things, Haitians do seem to enjoy confounding expectations. In fact, the official founder of the company, Jules Moscoso, came over from the Dominican Republic in the early 1900s and settled in a small town called Léogâne in Haiti (just SW of Port-au-Prince, the capital), which was a centre of the sugar economy for centuries and which remains the source for the current company’s cane.

Marie Mascoso

That’s just a convenient sort of dating though, because Jules ended up marrying into the local aristocracy (or petit bourgeoisie, depending how you look at it) of the Vulcains, who were large landowners possessing several sizeable tracts of land and cane fields. Jules’s wife Marie confuses the timeline, since he established the distillery…but she and her relatives going back about five or six previous generations had been making and selling clairin the whole time (they also owned several general stores, which made distribution much easier). Jules and Marie’s descendant – Michael Moscoso, the current owner – calls himself a third generation distiller because the paper trail only begins in 1925, with Jules and some old barrels that were imported – the company, such as it was, was never formally incorporated and was simply known as Mascoso’s. He does not recall if any single pot stills were utilized in making their clairins, but to his knowledge the original distilling apparatus consisted of combination of pot and creole column still of five to six plates, copper made, with direct fire or water baths (which was and remains very much the tradition across the whole island). As Haiti had once been a French colony, its influences came from the other French islands, explaining the Charentais alembics that were more common, as opposed to single pot stills used in other parts of the Caribbean by indigenous producers.

Jules was more than just a local hooch handler. He was in fact quite a talented tinkerer and very good with his hands: mechanical common-sense ran in the family, and much of the distillery was constructed with his direct input. The story goes that at one time, the French government donated a bleacher (those stadium like prefab metallic rows) to the Haitian government of the time. This bleacher was designed by Gustave Eiffel (of Eiffel tower fame), but for some reason the assembly instructions accompanying the bleachers came in Chinese (don’t ask). The minister of public words of the moment, a bona fide engineer, confessed to Jules – a friend of his – that he couldn’t build it. Jules casually asked for the manual, came back seven days later and then built the thing in fourteen days. It was famously known as the “Estrade du Champs de Mars” and is unfortunately no longer in existence…but any Haitian from that era would know of it.

The whole family was in on the business and it did not limit itself to merely clairins. Over time they expanded to providing 95% alcohol and ethanol to hospitals and pharmacies, base rhum stock to other clairin makers on the island and even branched out into the manufacture of essential oils (one such oil went on to provide the base for what would become Chanel No. 5). Aunts, cousins and uncles were all part of the operation and were involved in running both wholesale and retail part of the company and its various sidelines.

The business passed on on to the second generation (Edouard Mascoso) in the late 1950s and Barik fared reasonably well. Clairin sales (bulk and retail) and manufacture held steady, but the industry on the half island was moving into the direction of larger distilleries using industrial sized column stills which left smaller establishments at a disadvantage. Barbancourt remains the best known, and the late 1970s also saw the increased scale of other major producers like the Nazon family who make rhums under the banner of Distillerie de la Rue in Cap Haitian, and Michael’s own uncle Gerald Moscoso (of Ayiti Aromatik SA) who with is partner bought press and plant from around the Caribbean, and make the Kleren Nacyonal and other brands out of St. Michel. Slowly the business stagnated and regressed in the 1970s to the point where Edouard was forced by both this and his own health to drastically ramp down production in the 1980s. There followed a period of about twenty years when Mascoso / Barik as a clairin maker almost disappeared, though as noted, other branches of the family did have rhum operations of their own (and with confusingly similar brand names). All the while, though, a trickle of the juice kept coming, even if only for local consumption.

Michael Mascoso with two of his klerens

After some years of puttering around from job to job (including that of a DJ), Edouard’s son Michael “Didi” Mascoso, who had been brought up in the culture of his family’s businesses and had apprenticed with his uncle’s more modern clairin operation, took over the near-abandoned clairin distillery in 2008. From the inception, his ambition had been to move away from local bathtub-style popskull with poor quality controls and wide batch variations, to something more professional. In short he wanted to create a double-distilled and aged rhum that could not only elevate the product and sales on Haiti, but be of sufficient quality for export. It was of course not quite as simple as he had initially thought, but nevertheless he wanted to reopen a refurbished distillery with the same equipment, repaired and spiffed up, and tried to bring in more modern improvements and innovations over time.

It should be pointed out that it is almost a Haitian tradition to have one’s stills and factory infrastructure look as rundown and beat up as is humanly possible without actually ceasing operation. Part of that has always been the rather unsavoury, unglamorous, peasantlike back-country reputation possessed by the clairins themselves – why spruce up the still when the juice is just being sold to the proles? But more importantly, it keeps the eyes of the authorities off one’s operations if is just perceived as some small fly-by-night family outfit brewing small quantities of moonshine. According to Michael, life under the dictatorial Duvaliers was never as brutal as the western media made out. “Under Duvalier I was not aware of any challenges. During that time if one minded his own business and walked a straight line they were safe.” But the taxman was something else again. The moment one’s operation looked a little too professional or the infrastructure too modern, and bottling became part of the company output (factory bottling in real bottles with labels and stuff), then the taxman came sniffing around. And that was the major reason why 99% of the Haitian rum industry stuck with their old fashioned stills, and steadfastly refused to move ahead and modernize.

For financial and resource reasons, to recreate or even upgrade a functional distillery was very difficult for Michael. However, humans are nothing if not inventive, and much like to soviets in the 1970s and 1980s who were known for putting together amazing inventions with string, baling wire and some vodka (or in modern times, having the tightest code due to limitations on available computer time in the old days), there was a lot of knowledge, passed-down-lore and plain experience…and a strain of Jules’s talent for mechanical tinkering and skill with his hands was still in the family tree. The distillery was repaired and refurbished, essentially by dint of diligent scrounging: abandoned kitchen equipment, commercial supermarket freezers, coolers (any source of metals that could be found, really), wires, electrical stuff – steel and copper and plate and everything else, down to the screws. And then, as Michael put it, not without a hint of pride, “…watch us do magic by building our own pot and column stills, tubular condensers…. We also took old gas or #2 oil steam boilers and converted them into burning bagasse. A typical modern distillery here in Haiti, with a steam boiler, pot column…more than 90% built on the premises with scrap metal.”

Scrap and scrounging, begging and borrowing, doing it all manually, all this was fine – it was, nevertheless, expensive. It took all of Michael’s savings, credit cards, personal loans, raiding the family treasure chests (when not locked or guarded by fierce aunties) and getting help from his father and his brother (also named Jules)…and eight months after taking over, the still was ready to begin production. At this point Edouard struck a co-production deal with a competitor which caused Michael to withdraw from operations for a while. In December 2008 a successful test run on the distillery was finally done, and commercial production began in January 2009, with the intention of making both bulk clairin distillate for the local producers and possible export sales, and a line of white, caramelized and infused rhums.

Bad luck seemed to dog the distillery at the inception. First there was the lack of funding for upgrades which had stretched the repair job into nine months; then there was the co-production deal that diverted attention and resources from the Barik brand; the earthquake hit in 2010 and shattered much of the island’s infrastructure …and as if all this wasn’t enough, there was an increasing incidence of industrial scale ethanol being used to make cut-rate clairins. Clairins are enormously pungent and flavourful and what producers were doing was mixing in a small portion of true distillate with the ethanol to make cheaper, low quality “clairin” that dragged down sales of the real McCoy.

Michael: “Although we had the ambition of branding and bottling rhums since 2009, financials did not allow it. When things went from bad to worse in 2014, with the importation of industrial ethanol reaching its peak at that time, that was the end of selling bulk clairin. I therefore decided to switch my focus to bottling and move away from the bulk sales.” Michael noted that he had started working on his formulas and other blends since before the earthquake. “I started with my sugar mash premium rhum right off the still, filtered and straight in the bottle; a few other blends like the Marabou (a caramelized version of the premium), a mint infused one and a few other tropical fruits infusion…and boom I was in business. Selling a few bottles privately to a few customers in Europe but mainly France, I noticed that they have a preference for white agricoles — so I started bottling the Traditional 22 which is the pure juice version.”

So far the company remains (in accounting parlance) a sole trader operation and has not been officially incorporated. It is informally known and will one day be established in law as Moscoso Distillers, and under its umbrella have issued the Kleren Nacyonal and Rhum Barik brands, with additional variations of these (there’s also a rum-based Amaretto di Moscoso). Sales remain slow and relatively minimal as a consequence of both novelty and a nonexistent mass-marketing advertising budget – in that sense, as Michael observed, a debt of thanks is owed to Luca for putting clairins on the international map and raising the drink’s profile. He hopes that his prescence at the 2017 Paris RhumFest will establish his brand more firmly in the mind of the rhum loving public and perhaps lead to more investment and possibly another large Haitian brand. Having a personal thing for these potent unaged white rhums, as well as being interested in how the ageing would be handled, I for one will certainly be keeping an eye out on his products going forward.

Other notes

The word “Barik” means barrel in Haitian creole. The choice of the name for brand (and possibly the company) was deliberate, because it was such a strong, easily pronounceable title in any language (Rolex, as I recall, chose its name for similar reasons).

Originally Michael wanted to name his product “Rhum La Guldive” but felt it to be too challenging a name. It would be hard to ask for in a bar, the way one says “Havana Club” or “Bacardi”. Plus, Pere Labat next door might launch a lawsuit over the name since they have a product with that title.

All photographs are from the Barik Facebook page, used with Michael Moscoso’s permission

References

The short list below, of rhums Mascoso Distillers makes, is not exhaustive (I’ve excluded all flavoured and infused versions since my focus is not on such products) but it’s a start for those who are interested.

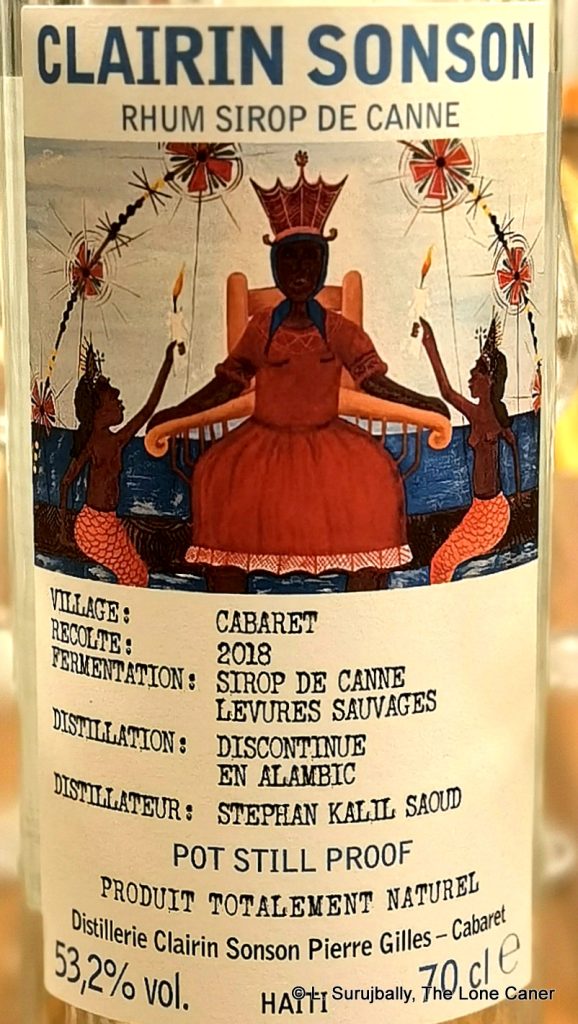

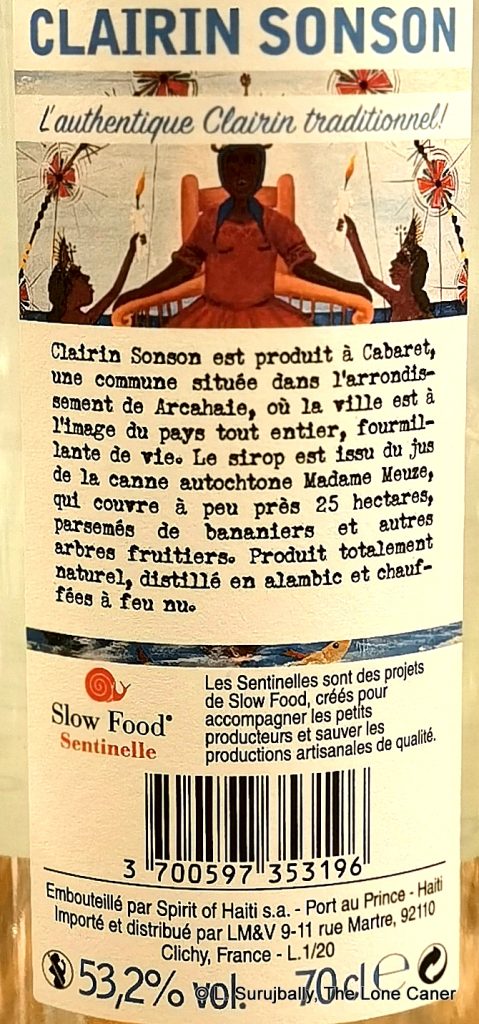

Initially, clairins from three distilleries were released (Sajous, Casimir and Vaval) a fourth (from Le Rocher) was selected and became part of the canon in 2017, and in 2018 a fifth was put together from a small distillery in Cabaret called Sonson — which is, oddly enough, not named after either the owner, or the village where it is located. It was finally released to the market in 2021, but the cause for the delay is unknown. The rum, like Clairin Le Rocher (but unlike the other three) is made from syrup, not pure cane juice; and like the Clairin Vaval, derives from a non-hybridized varietal of sugar cane called Madam Meuze, juice from which is also part of the clairin Benevolence blend. All the other stats are similar to the other clairins: hand harvested, wild yeast fermentation, run through a pot still, bottled without ageing at 53.2%.

Initially, clairins from three distilleries were released (Sajous, Casimir and Vaval) a fourth (from Le Rocher) was selected and became part of the canon in 2017, and in 2018 a fifth was put together from a small distillery in Cabaret called Sonson — which is, oddly enough, not named after either the owner, or the village where it is located. It was finally released to the market in 2021, but the cause for the delay is unknown. The rum, like Clairin Le Rocher (but unlike the other three) is made from syrup, not pure cane juice; and like the Clairin Vaval, derives from a non-hybridized varietal of sugar cane called Madam Meuze, juice from which is also part of the clairin Benevolence blend. All the other stats are similar to the other clairins: hand harvested, wild yeast fermentation, run through a pot still, bottled without ageing at 53.2%. The surprising thing is, the palate is almost like a different animal. It’s luscious, it’s sweeter, more pungent, more tart. It channels watery, rather mild fruits – melons, pears, papaya – which in turn hold at bay the more sour elements like unripe pineapples, lemon zest and green mango chutney: you notice them, but they’re not overbearing. Somewhere in all of this one can taste mineral water, crackers and salt butter, the silkiness of a gin and tonic and the musky dampness of moss on a misty morning. It’s only on the finish that things finally settle down to something even remotely resembling a standard profile: it’s medium long, a little sweet, a little sour, a little briny, tart with yoghurt and a last touch of fruits and sweet red paprika.

The surprising thing is, the palate is almost like a different animal. It’s luscious, it’s sweeter, more pungent, more tart. It channels watery, rather mild fruits – melons, pears, papaya – which in turn hold at bay the more sour elements like unripe pineapples, lemon zest and green mango chutney: you notice them, but they’re not overbearing. Somewhere in all of this one can taste mineral water, crackers and salt butter, the silkiness of a gin and tonic and the musky dampness of moss on a misty morning. It’s only on the finish that things finally settle down to something even remotely resembling a standard profile: it’s medium long, a little sweet, a little sour, a little briny, tart with yoghurt and a last touch of fruits and sweet red paprika.