Soft. This rum is so soft. It is breezes in the warm tropical twilight, the lap of waves at low tide on a deserted Caribbean island, the first unsure, hesitant and oh-so-sweetly remembered kiss of your timid adolescence. It is your mother’s kitchen on a rainy day, fresh bread baking in the oven. It is a 40% Peruvian piece of magic, and if it costs a shade over a hundred bucks, I can only say that I believe it to be worth every penny. Want a slightly pricey introduction to sipping quality rum that seduces, not assaults? Here it stands.

I asked the question of the Ron Millonario 15 Solera whether that was the best solera in current commercial production, and had to say no, largely on the strength of this one – not because the XO is better: it’s simply as good in a different way. Note that both rums are made in the solera system from a Scottish column still distillate; the 15 is made from a four barrel solera, but the added richness of the XO makes me suspect (like my Edmontonian friend does) that either this is a five barrel system, or they aged it longer somehow. Details remain sparse. The two are almost twins with obscurely opposing characters, and while the 15 is cheaper and therefore better value-to-quality overall, I must concede that on a complete aesthetic, the XO probably has it.

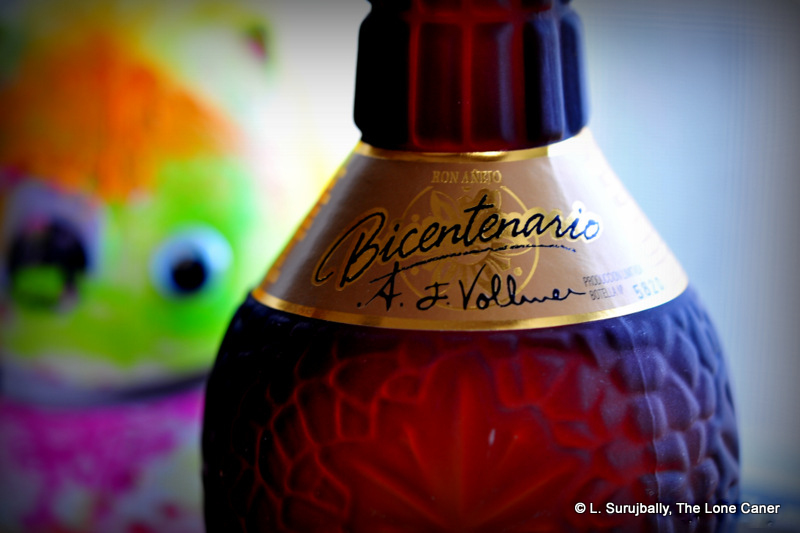

Consider the appearance, which would probably make my departed Maritime friend the Bear weep with happiness: cheap black cardboard cutout that won’t add to the price, embracing a flattened squarish bottle that has handsomely gold etched lettering and a faux-golden tipped cork. It looks just classy enough to not be considered a cheap knockoff aspiring beyond its pedigree.

I should remark right at the outset that the XO is a rum deserving to be savoured, not swilled, because while the nose began just swimmingly – honey, a slight minty zest, mango and papaya and flowers – it only got better as it opened up, adding a delicate green and vegetal background, and subtle aromas of coriander and brown sugar. I tried this in tandem with the Millonario 15 solera and that one was excellent also, but it was eclipsed by the sheer complexity of this baby.

And the taste, nice. Again, gets more complex and interesting as time goes on: right off the bat I was enthused about its gentle, velvety smoothness (not altogether surprising for a 40% solera), and the arrival of white chocolate, buttery, creamy caramel. A shade heated without malice, spicy without bitchiness, which was a perfect offset for the sweet notes that coiled around it. That sounds straightforward enough but tek a chill and wait (as my brother back in Mudland would say). Just like with the nose, further flavours shyly emerge and when I tell you that I got a slight smokiness, old dusty leather, fresh fruit and white flowers all in tandem, you can understand why everyone I’ve ever shared this with sings its praises. I’ve already distributed a bottle or two in tasters over a mere few months (and that’s phenomenal given my hermitlike nature and how few friends I have who like rums). As for the exit, it is excellent, chocolate-like (of the milk kind), smooth, long and departing with a last mischievous fillip of those fruity notes.

In fine, unlike the 15 which began well but simply stayed at that level of excellence, the XO started slowly, built up a head of steam and then gently and powerfully released its character over time. For sure this is not a mixing agent, and it rewards the patient – it gets better as it opens up. I’m not sure a higher proof would improve this marvellously made Peruvian product, and I’m not asking for it to be made so (though I might not object either). It’s great as is…don’t mess with it, except perhaps to dial down the sweet a shade.

If you are a raw, uncompromising Caledonian or his Liquorature acolyte (did someone say “Hippie”?) who likes harsh briny sea salt in your beard and the wind in your face and peat in your cask-strength drink, then the softness and relative sweetness of this rum, harking as it does of sunlight and warmth instead of rocks and northern waves, is definitely not for you. The cask strength whiskies are savagely executed Goyas compared to Ron Millonario’s voluptuous females painted by Raphael and Titian, so it comes down to taste and character and preference. My own take is merely that the makers of Ron Millonario XO Especial, with this lovely rum, have pressed all the right buttons and made all the right incantations in producing a rum that raises the bar of rums in general, and soleras in particular. Yet again.

(#127. 88/100)

Other Notes:

- 2024 Video recap is here.

- Like most solera rums, this one is sweeter than the average and that may be off-putting to drinkers who prefer a drier, sharper and more ascetic “rum-like” profile. Personal preferences therefore have to be taken into consideration when deciding whether to buy it or not.

- In 2019 the Millonario Cincuenta (“50”), a 10th Anniversary companion to this rum, was issued. It was also added to. I reviewed it in 2020 with a much more modest sub-80 point score.

Update August 2016

In the years since this review came out — I tried it in 2012 — I’ve taken a lot of flak for my positive assessment of the two Millonarios. Fellow reviewers and members of the general public have excoriated the rum for being loaded – destroyed – with so much sugar as to make it a “candied mess.” I acknowledge their perspective and opinions, but cannot change the review as written, as it truly expressed my thoughts at that time. Moreover, the complexity I describe is there and cannot be wished away, and if the rum is too sweet for many purists, well, I’ve mentioned that. About the most I can do at such a remove — short of shelling out for another bottle and trying it — is to suggest that if sweet isn’t your thing, deduct a few points and taste before you buy.

And a note for people now getting into rum: sweet is not a representative of all rums, least of all high end ones. The practice of adding sugar in any form to rums, to smoothen them out and dampen bite (some say it is to make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear), is a long-standing one, but gradually being decried by many who want and prefer a purer drinking experience (Plantation and Rum Nation are two companies which sometimes engage in the practice, which they term “dosing”). It remains legal in many rum producing nations. As with most aspects of life, sampling a variety will direct you to where your preferences lie.