It is appreciated that the lion’s share of the credit for Guyanese rums goes to Demerara Distillers Limited, who have the spirituous equivalent of a killer app in the famed stills and have capitalized on that big time. In fact, their rums are so unique and well known that they have become stand ins for the entire class of “Demerara Rums”. However, DDL is in fact something of a late entrant to the field, formed in the 1970s by the consolidation of older sugar estates held by departing UK companies like Bookers or Sandbach Parker. A far older brewing company exists in Guyana, that of Banks DIH, and although DDL has gained equal shares of international acclaim for its rums (and opprobrium — there’s that dosing issue, remember?) Banks stands apart for two reasons – locally, up to the point I left the country in the 1990s, the population’s drink of choice was not the DDL King of Diamonds, but Banks’s XM five year old and XM ten year old rums (most citizens could not afford the DDL ED-12 or ED-15, which were primarily for export anyway); and secondly, no whiff of adulteration ever touched their own products (though Wes Burgin of the FatRumPirate disputed that and I’m hoping he gets back to us with some of his hydrometer tests to settle the issue).

(c) National Trust of Guyana.

Perhaps to the detriment of the rum world, Banks does not focus as tightly on rums as its main competitor (though over the decades DDL has also diversified quite substantially, into markets outside its core competency). That’s because it is not, strictly speaking, into rum for the majority of its revenues: it is a financial and food & beverage conglomerate, with franchises, licensing agreements for foreign drinks, and makes and distributes rums, wines, vodkas, beers, soft drinks, bottled water and a plethora of snack foods. It owns its own bank (the Citizen’s Bank) and has fast food joints and retail operations around the country. Given the small footprint of the XM brand worldwide and lack of prominence in their annual report (yes, I read it), that can come as little surprise.

So, outside the Caribbean and expatriate Guyanese enclaves, Banks’s XM rum is not that well known – indeed, apart from the odd review here or there, or a tourist bringing back a bottle, when was the last time you heard their rums mentioned? They are certainly not the same as the perhaps better-known (Bacardi produced) Banks 5-island 7-island rums (made by a UK based blender whose brand was named after a British naturalist who sailed with Captain Cook on the Endeavour). But this disguises a history that goes back more than a hundred and fifty years, and has almost always been run by and generally associated with, a single family, the D’Aguiars of Georgetown.

The property of D’Aguiar’s Imperal House by Stabroek Market (the clock tower for which can be seen on the far left) in the 1950s

Officially, the core company of D’Aguiar Brothers was formed in 1896, when the four sons of Jose Gomes D’Aguiar – one of the Portuguese diaspora who came to the colony subsequent to the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1838 – created the partnership after the death of their father three years earlier. But Jose had himself been in business since the 1840s and laid the foundation for the commercial activities of his family when he started a retail spirits shop (let’s be honest and call it by its local title, a “rumshop”), which rapidly expanded into a chain of such establishments. Boozing being as popular then as now, by 1885 Mr. D’Aguiar had sufficient capital to not only open a cocoa and chocolate factory, but also (and perhaps more importantly) a shipping agency. This became more crucial once the partnership mentioned above was created, because the first part of an ambitious expansion plan was the purchase of the buildings belonging to the Demerara Ice House. These buildings included a hotel, a number of bars, and a plant that made aerated soft drinks. The Ice House itself was named because it was the company that shipped in ice from Canada using schooners, so it dovetailed nicely with the brothers’ own shipping company, to say nothing of the drinks they were now selling.

The company continued under the leadership of the partnership, and gradually turned into a sole proprietorship as the brothers died one by one. In 1929 the last remaining son of old J.G. (also called Jose Gomes), a doctor, died. Curiously, lands upon which the leased buildings stood (they were leased from the crown) were finally purchased outright in that same year, but this created cash flow problems and without a dynamic CEO at the helm, the company – which by now was a limited liability concern called D’Aguiar Brothers – started on a downward spiral. The chocolate and cocoa business and shipping agency were sold off, and Mrs. D’Aguiar, J.G.’s widow and principal shareholder, kept things running in spite of being made an offer of $100,000 (an insignificant sum even by the standards of the age), waiting for her youngest son Peter to become ready to take over. She felt that he alone had the business savvy to turn the company around and revitalize it. He became the Managing Director in 1934 at the age of 22.

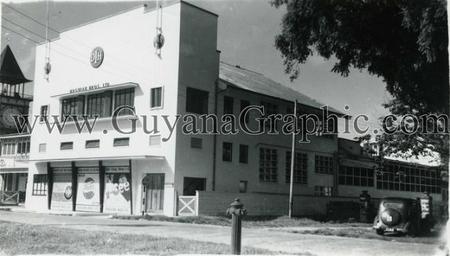

Photo (c) Banks DIH

Mr. Peter D’Aguiar was everything his mother hoped he would be. He concentrated on the manufacture of soft drinks and rum (the monopoly of the ice house continued as a cash generator, and even in the 1990s it still sold ice blocks for parties and catered events though of course by then they were making their own), and borrowed heavily to refinance the business and its expansion. Things stabilized during the 1930s, debts were paid off and it became self-sustaining. In 1942 D’Aguiar Brothers acquired the first South American franchise for Pepsi Cola, and ten years later the soft drink brand of I-Cee was launched (it remains one of the main soft drinks sold locally). The production of the XM brand of rums which had been in production since the early 1900s, was expanded and with the fragmented nature and bulk export of rums by other producers based on the estates run by Bookers and Sandbach Parker, was the most popular rum in British Guiana. It was always, it should be noted, a blended rum, sourced by the family members going around the various distilleries and estates up and down the coast and buying their rum in bulk. The company never invested in a distillation apparatus of its own, and the rum was based on the expertise the family had brought over from Madeira — and the production of specifically aged blended rum (10 years old etc), was many years in the future. What Mr. D’Aguiar did was focus on self reinforcing business lines – the soft drink factory, the rum bond, the bottling plant, liquor store, retail bars and the hotel. To this was added Banks Breweries as a separate company (a public one, another innovation) in the mid 1950s – it made, bottled and sold Banks Beer, also a brand which remains extant to this day. In fact, for decades, way before fast foods hit the country in the late 1990s and early 2000s, D’Aguiar’s ran the extremely profitable Demico House burger and pizza joint from their property (which included most of the foregoing businesses) that was across from both Stabroek Market and Parliament Building.

By the year of Independence of British Guiana (1966) the various areas of company involvement had become so complex that some consolidation was in order, and the structure of the various organizations was folded into a single overarching public company, D’Aguiar Bros. (D.I.H.) Limited (the DIH supposedly meant D’Aguiar’s Imperial House, a change from the Demerara Ice House); in 1969 this was further amended by adding Banks Breweries into a new conglomerate called Banks DIH, with the DIH now standing for D’Aguiar’s Industries and Holdings. They relocated that same year to a portion of South Georgetown close by Houston Estate where the brewery was already located, which they christened Thirst Park, and built a round office complex called the Rotunda to be its head office (it remains a local landmark on the East Bank Highway).

Photo (c) PaulineandJohn2008 via Flikr

Unfortunately, rum took something of a backseat during the company’s development and expansion. Part of this was Mr. D’Aguiar’s interests in other matters, such as politics – he was the leader of the small United Force political party in the 1960s – and partly it was the scarcity of foreign exchange during a period of stringent exchange controls; but it was also to some extent company policy and culture. Rum was not “big ting” back then the way it is now, beer was, and Banks not only had a hammerlock on that in Guyana, but also in Barbados where they started another beer company in the 1960s, also called Banks (the two companies are now cross-shareholding parties). In the 1970s and 1980s, Banks DIH, seeing rum as one portion of its portfolio among many others, and being quite happy with the XM brand’s dominant role in the local marketplace, did not see the need to aggressively expand.

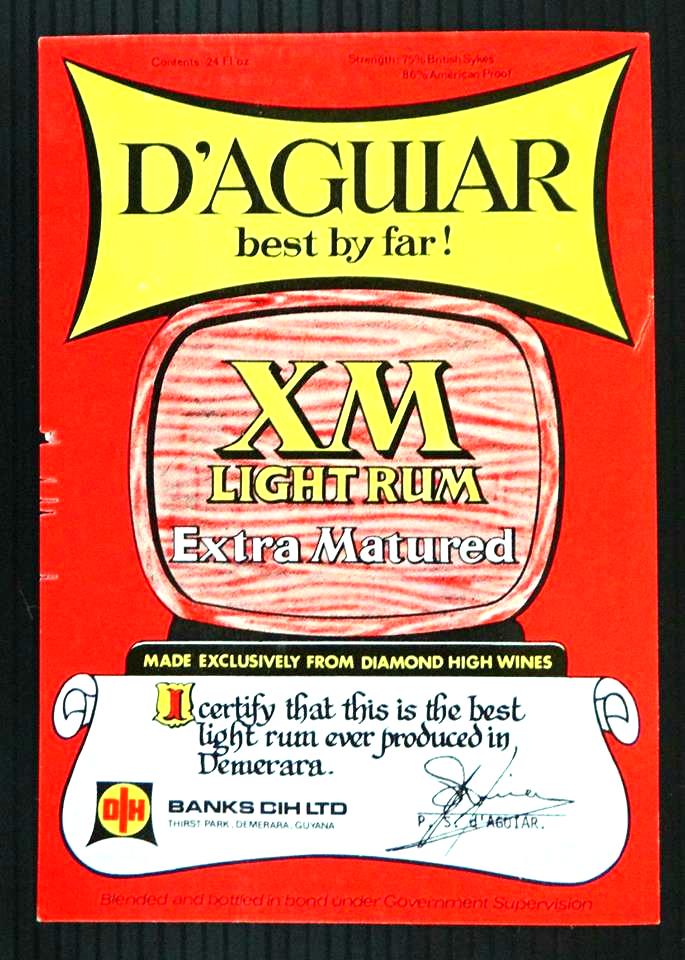

An old label from the 1960s, bearing the signature of Peter D’Aguiar

The Caribbean islands each had their local companies and lacked large consuming populations so did not present much of market potential. Exports to North America did take place, but were relatively minimal. So investing in a major upgrade to distillation operations to the tune of getting a pot or column still and starting to make bulk rum (which would in any case require a secure source of molasses or a sugar estate), took second place to tried and true blending operations. I lack direct proof for this, but I believe that in the years 1975-2000, most of the rum stock was bought from the Diamond Distillery, and Banks just blended and aged their own from that. By the 1990s Banks did have a 3 year old XM, a 5 year old, a wildly popular ten year old and a rare-as-hen’s-teeth fifteen year old which we heard, but I never saw. By contrast, DDL’s King of Diamonds brand prior to the introduction of the El Dorado line in 1992, was considered third tier bush rum at best, just a step above moonshine, or so many old porknockers told me when I worked with them – so it was not surprising that XM was a much more popular local rum.

Mr. Peter D’Aguiar died in 1989 and a new chairman, Mr. Clifford Reis took the helm: he has been the Chairman and Managing Director of the conglomerate ever since. Though well known for its food and beverage dominance (even in the face of increased competition from DDL and Ansa McAl) Banks has expanded into other fields, for example owning 51% of a local bank in 1998, and opening restaurants and fast food outlets. It is the agent and local distributor for Johnny Walker, Absolut, Smirnoff and various juices, snacks and other products, while also developing an export market for its beer (via Barbados) and rum. In all, as of 2017, the sale of beverages make up some 80% of Banks’s revenue and an equivalent proportion of its profit….but alas, how much of that is rum we can only speculate. What we do know is that as of this writing, XM rums are distributed in Antigua, Dominica, Trinidad & Tobago, France, Italy, New York, New Jersey, Florida and Canada.

(c) Peter’s Rum Labels, www.rum.cz

Speaking of which, getting back to the rums.

Not everyone saw 1992 for what it was, the beginning of the renaissance of rum in the eyes of the western world. Although of course the whisky makers had long been buying barrels of rum to age in Scotland, releasing them as aged special cask-strength editions for decades, they were at best a niche market; the real money was being made by selling bulk rum to blenders the world around (including Scheer). DDL helped change that by creating the 15 year old rum that was manufactured on location, in bulk (the amazing profiles of the stills certainly helped) so instead of a few hundred bottles of a single cask issued as something special and available only to the few, now scores of thousands of bottles of seriously aged juice were being exported all over the map. Within a decade, such five, ten, fifteen and 20+ year old rums were being made by practically all the big guns in the Caribbean – Appleton, Foursquare, Mount Gay and others.

Banks certainly jumped on the bandwagon, and any Guyanese of my generation will remember the dark blue label of the XM five year old, and the lighter one of the ten year old. The ten in particular was, I believe, exported to the UK, USA and Canada (verification needed). The lower priced sub-ten year old rums like the Gold Medal, the Royal Gold or the Extra Matured rums were all noted as being Demerara rums, since (at that time) the concept of geographical appellations and protections with respect to rums had yet to gather any steam and was mostly relegated to the French islands.

Banks certainly jumped on the bandwagon, and any Guyanese of my generation will remember the dark blue label of the XM five year old, and the lighter one of the ten year old. The ten in particular was, I believe, exported to the UK, USA and Canada (verification needed). The lower priced sub-ten year old rums like the Gold Medal, the Royal Gold or the Extra Matured rums were all noted as being Demerara rums, since (at that time) the concept of geographical appellations and protections with respect to rums had yet to gather any steam and was mostly relegated to the French islands.

Banks continued its past practice of sourcing rum stock from the distillers up the road at Diamond, who by the turn of the millennium had consolidated all the stills there, but obviously this was not a situation that could continue, since as DDL expanded its business operations globally under the leadership of its dynamic chairman Yesu Persaud, not only did it require its own stocks, but saw Banks as a potential competitor. Therefore, by the early 2000s DDL claimed a shortage of barrels and bulk rum and ceased supplying Banks with any at all, forcing Banks to turn to Trinidad (Angostura) and Barbados (Foursquare) for rum stock which they continued to blend. DDL kept up the pressure in the late 1990s and 2000s by offsetting the loss of bulk rum sales to Europe with an EU funding tranche to put in a new column still, while Banks, not seen as a distiller or true “rum company” did not upgrade its own facility to take advantage of the uptick in global rum appreciation and sales. To add insult to injury, when DDL was certified as the registered proprietor of geographical indication in 2017 for the label “Demerara Rum”, it and it alone could use the moniker for its rums and they filed an injunction against Banks’s labelling its products as such, and even stopped a shipment of XM that had arrived in New York until the labelling was “corrected”. Banks was therefore forced to cease referring to the XM line as Demerara rums (as were all other makers in the global marketplace) and this is why currently they are all now noted as being “Caribbean”.

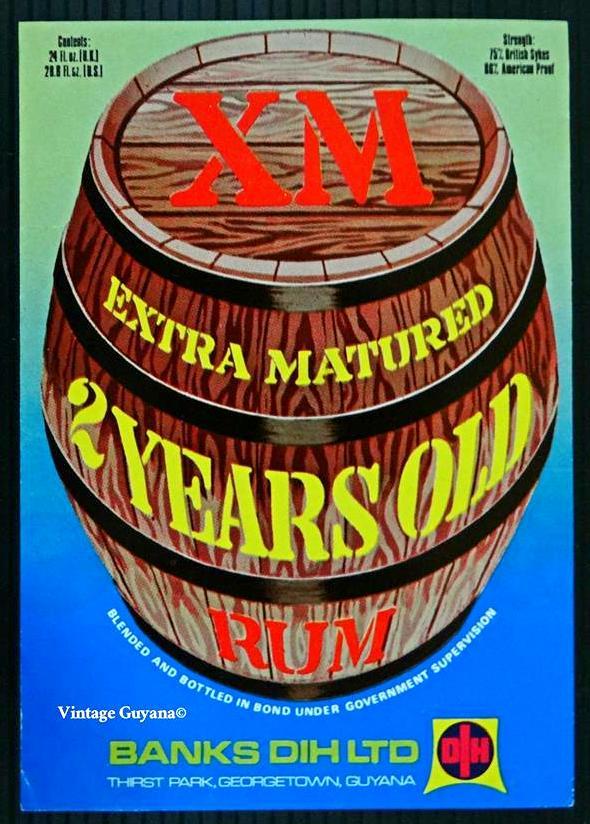

Vintage Banks DIH LTD XM Extra Matured 2 Years Old Rum Label. This is an old label from the late 1980’s and is now a discontinued product. (c) Vintage Guyana – History Preservation FB page

That said, XM’s rum blends have maintained their local popularity, not least of which is the XM 5 year old. Another rum, the XM 2 Year Old Brown, was introduced in the 1990s and promoted in concert with a local dish, duck curry, becoming so entwined with its own promotion that it’s known locally as “Duck Curry Rum”; and the Xtra White, developed in the 2000s remains a favourite and staple tippling rum in rural agricultural areas and the sugar estates, where its purported property of not creating a hangover gave it the housewive’s moniker of “Stay Home Darlin’ rum” – we can take that with pinch of salt, but it says something of how deeply the various rums Banks DIH makes have entwined themselves into the local culture to this day.

As far as Banks is concerned, I have no indication that this state of affairs will change. I know of no plans to purchase and install a still, column or pot. Blending not only remains the company’s core competency with respect to rum, but appears to be their preferred way forward, since it minimizes capital investment while staying true to the company’s roots. In any event, they seem to be quite good at it no matter what raw stock they use. For example, I heard a story that after the Xtra White Rum was introduced a few years back (with Angostura base stock) it immediately jumped up to a local 75% market share. When they started exporting it to Trinidad, it got a 50% market share, “cutting White Oak’s ass” as a friend of mine gleefully related, and Angostura threatened loss of supplies if they didn’t stop exporting it there. So certainly the skill to make decent rums exists. There may be plans to issue some cask strength versions of the XM line in the future, and certainly the export market to the USA and Canada will be more aggressively pursued.

Whatever the case, whether Banks DIH continues along the current steady course or radically revamping their rum lineup, the fact is that they have a long and distinguished heritage of their own. No history of Guyanese rums could possibly be complete without mentioning the company at least once. It remains one of the most successful organizations in the country, a local icon, and one with its own unique rum-making tradition which deserves recognition and acknowledgement every time Guyana and rum are discussed.

Banks DIH Rums (as known)

- XM Millenium 12 Year Old Rum

- XM Royal Extra Mature Demerara Rum*

- XM Extra Matured 2 YO Rum*

- XM Gold Medal Demerara Rum*

- D’Aguiar’s XM 5 Year Old Demerara Rum*

- D’Aguiar’s XM Light Rum

- Hard Ball Rum

- Supreme High Wine (69% White)

- XM Over Proof (65%)

- XM Classic Light Rum

- XM Xtra White Rum

- XM Mild & Dry Rum

- XM VXO 7 Year Old Caribbean Rum

- XM “Royal Gold” 5 Year Old Rum Caribbean Rum

- XM “Royal Gold” 10 Year Old Caribbean Rum

- XM “Special” 12 Year Old Caribbean Rum

- XM “Superior” 15 Year Old Caribbean Rum

- XM Golden Jubilee 20 Year Old Special Reserve Rum

* = Discontinued

Sources

- Some stats and rehashed history (see ¼ down the page for Banks)

- Peter’s Rum Labels are an amazing resource

- DDL’s 2017 gaining the GI designation of “Demerara”

- Miscellaneous points about the company, cultural and historical

- Banks DIH exports to USA

- Banks DIH 2017 Annual Report

- Current in-production rums

- Banks DIH history from their own web page

- Some old photos of the Stabroek area in Georgetown can be found on the National Trust website.

- Emails, conversations and messages with the Guyanese diaspora

- My own experience in Guyana 1976-1995 informs some of the background.

Just a short comment to confer my appreciation of these great background pieces you write. This one is again very interesting, a pleasure to read!

Cheers,

Emile

Once again a great piece of history. I really love those maker portraits and am deeply impressed by their historical accuracy and depth of knowledge. Looking forward to the next ones.

I’ve read the whole stuff about xm rum, but one thing I’m not pleased with is that my dad vernon hector Dundas name was never mention as part of making xm rum with banks d.i.h, my father (r.i.p dad) had worked and served this company for 32 years , he was the chief rum blender for the rum factory, retired 1998. Hmmmmm years I’m going through every thing about banks rum and yet I can’t see no appreciation of his hard work and dedication as an senior staff.

I completely understand your frustration. A lot of people who contribute do not get the mention they deserve. I run into this issue constantly in my researches.

The fact is though, that I’m not writing a book with personal visits to Guyana, detailed interviews and deep research from Banks’ archives. I’m working with publicly available materials and online newspapers and those contacts I have who respond or put me on to yet others.

So, point me to published reference to your father’s name and achievements, which I could potentially use. I’d love to include them. But if nobody mentions it in my queries and emails, and nobody remembers, I’m afraid that, like many unheralded and unacknowledged contributors to the field, he will be forgotten except by family members and close friends, and those who cherished the work he did while he did it. And that is our loss.