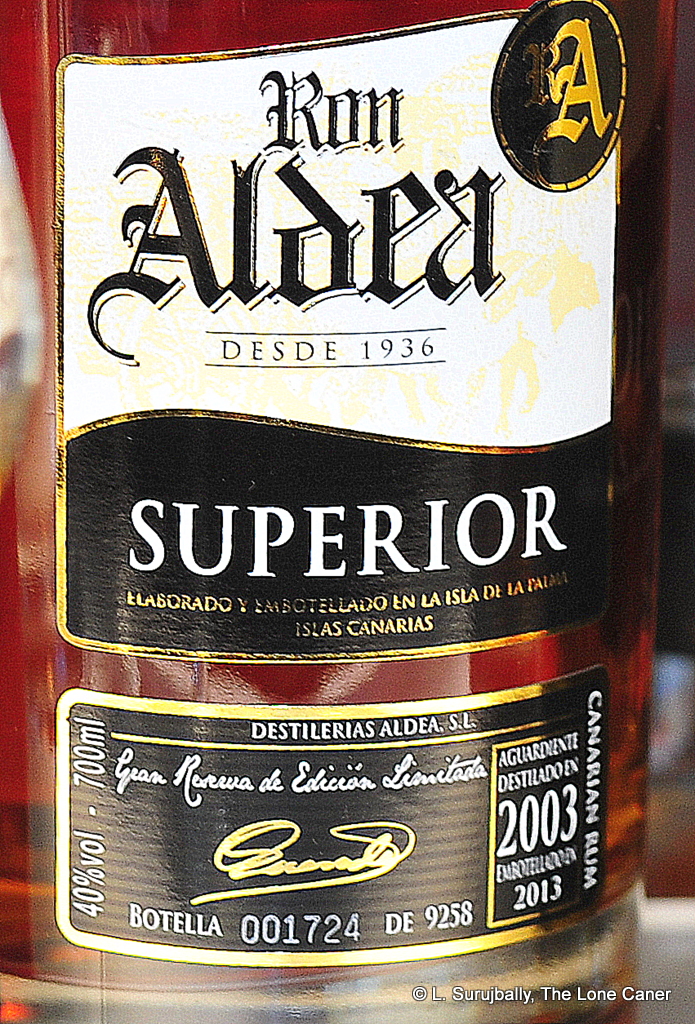

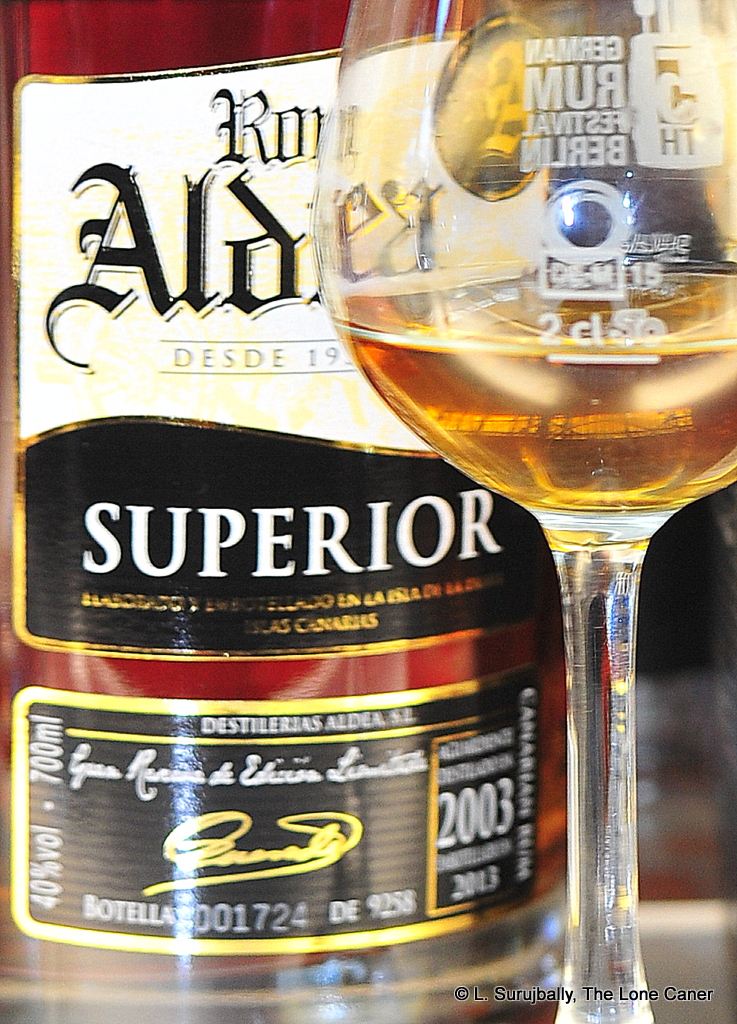

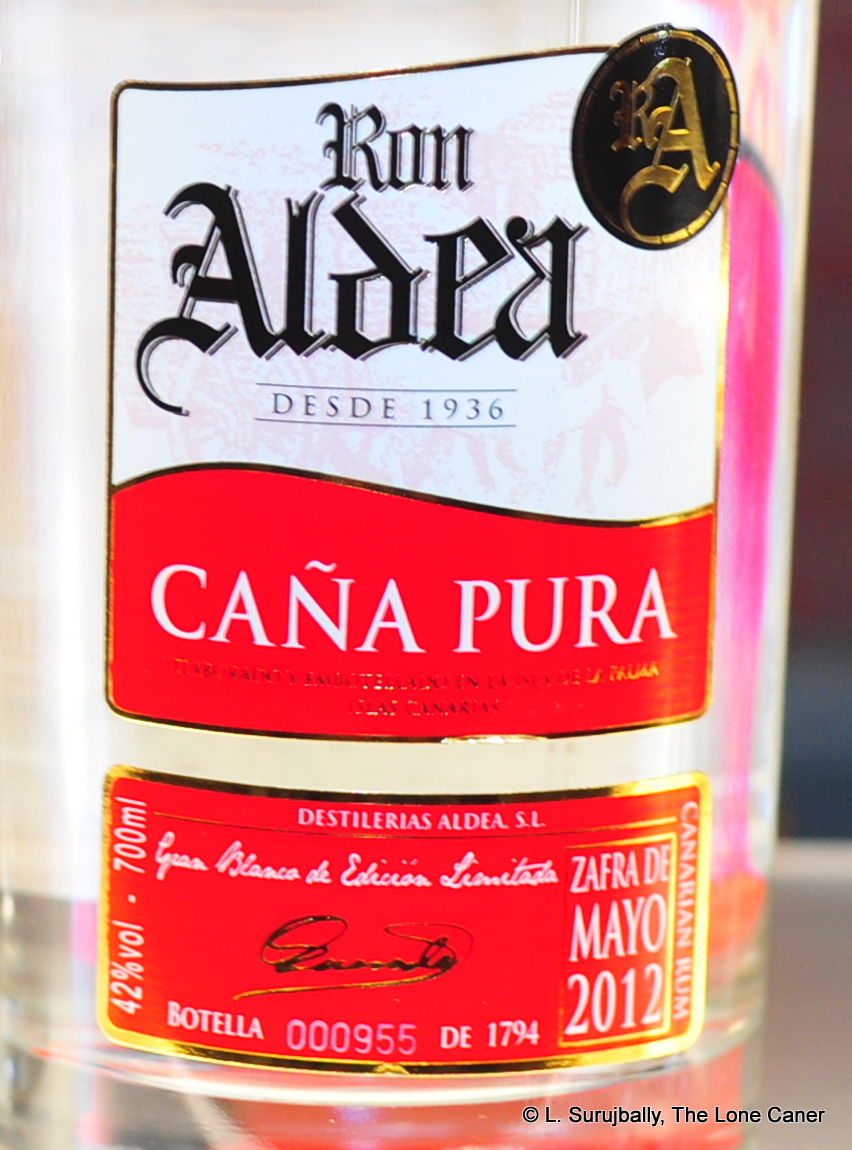

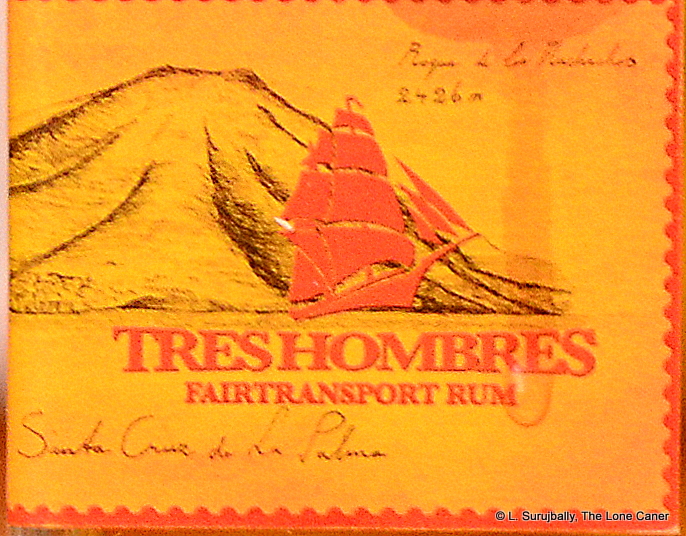

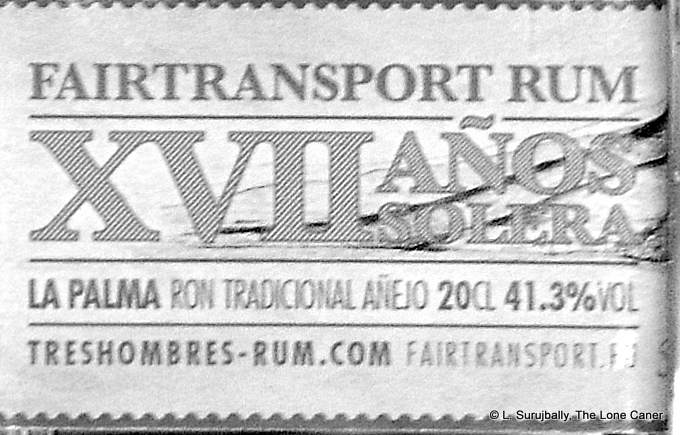

Before delving into the (admittedly interesting) background of Tres Hombres and their “fair transport” concept, let’s just list the bare bones of what this rum supposedly is, and what we do and don’t know. To begin with, it’s unclear where it’s from: “Edition No. 8 La Palma” goes unmentioned on their webpage, yet Ultimate Rum Guide lists a rum with the same stats (41.3% ABV, la Palma, Solera) as Edition No. 9, from the Domincan Republic. But other La Palma rums made by Tres Hombres list the named rums as being from the Canary islands – Aldea, in point of fact, a company we have met before in our travels. Beyond that, sources agree it is a blended (solera) rum, the oldest component of which is 17 years old, 41.3% and the three barrels that made up the outturn spent some time sloshing around in barrels aboard a sailing ship (a 1943-constructed brigantine) for which Tres Hombres is renowned.

Well, Canary Islands or Dominican Republic (I’ll assume The Hombres are correct and it’s the former), it has to be evaluated, so while emails and queries chase themselves around, let’s begin. Nose first: kind of sultry and musky. Green peas developing some fuzz, old bananas, vanilla and grated coconut, that kind of neither too-sweet nor too-salt nor too-sour middle ground. It’s a little spicy and overall presents as not only relatively simple, but a little thin too, and one gets the general impression that there’s just not much gong on.

Well, Canary Islands or Dominican Republic (I’ll assume The Hombres are correct and it’s the former), it has to be evaluated, so while emails and queries chase themselves around, let’s begin. Nose first: kind of sultry and musky. Green peas developing some fuzz, old bananas, vanilla and grated coconut, that kind of neither too-sweet nor too-salt nor too-sour middle ground. It’s a little spicy and overall presents as not only relatively simple, but a little thin too, and one gets the general impression that there’s just not much gong on.

The palate, though, is better, even a little assertive. Certainly it’s firmer than the nose led me to expect. A trace briny, and also quite sweet, in an uneasy amalgam akin to tequila and sugar water. Definite traces of ripe pears and soft apples, cardamom and vanilla. Some other indiscernible fruits of no particular distinction, and a short and rather sweet finish that conferred no closing kudos to the rum. It’s as easily forgettable and anonymous as a mini-bar rum in a downmarket hotel chain, and about as exciting.

Tres Hombres is now up to No. 34 or something, includes gin in the lineup, still do some ageing onboard for a month or so it takes to cross the Atlantic and certainly they have not lost their enthusiasm — they include rums from Barbados, DR and the Canary islands. Whether this part of their business will carry them into the future or forever be a sideline is, however, not something I can answer at this time – the lack of overall publicity surrounding their rums, suggests they still have a ways to go with respect to wider consciousness and acceptance.

Tres Hombres is now up to No. 34 or something, includes gin in the lineup, still do some ageing onboard for a month or so it takes to cross the Atlantic and certainly they have not lost their enthusiasm — they include rums from Barbados, DR and the Canary islands. Whether this part of their business will carry them into the future or forever be a sideline is, however, not something I can answer at this time – the lack of overall publicity surrounding their rums, suggests they still have a ways to go with respect to wider consciousness and acceptance.

And with good reason, because to me and likely to others, complexity and bravura and fierce originality is not this rum’s forte – smoothness and easy drinkability are, which is something my pal Dave Russell has always banged me over the head about when discussing Spanish style rums, especially those from the DR – “they like their stuff like that over there!” And so I mention for completeness that it seems rather delicate and mild – the low strength is certainly responsible for some of that – and not completely displeasing….just not my personal cup of tea.

(#771)(75/100)

Other Notes & Background

This is one of those cases where the reviewer of the rum has to firmly separate the agenda and philosophy of the company (laudable, if somewhat luddite) from the quality of the rum they sell. In no way can the ideals of one be allowed to bleed over into the perception of the other, which is something a lot of people have trouble with when talking about rums made by producers they favour or who do a laudable public service that somehow creates the uncritical assumption that their rums must be equally good.

Tres Hombres is a Dutch sailing ship company begun in 2007 by three friends as a way of transporting cargo — fair trade and organic produce — across and around the Atlantic, and they have a sideline running tours, daytrips and instructional voyages for aspiring old-school sailors. In 2010, while doing some repairs in the DR, they picked up 3000 bottles of rum, rebranded it as Tres Hombres No. 1 and began a rum business, whose claim to fame was the time it spent — after ageing at origin — abroad the ship itself while on the voyage. Not just old school, then, but very traditional…more or less. The question of where the rum originated was elided – only URG mentions Mardi S.A. as the source, and that’s a commercial blending op like Oliver & Oliver, not a real distillery.

What the Tres Hombres have done is found a point of separation, something to set them apart from the crowd, a selling point of distinction which fortunately jives with their environmental sensibilities. I’m not so cynical as to suggest the whole business is about gaining customers by bugling the ecological sensitivity of a minimal carbon footprint – you just have to admire what a great marketing tool it is, to speak about organic products moved without impact on the environment, and to link the long maritime history of sailing ships of yore with the rums that are transported on board them in the modern era.