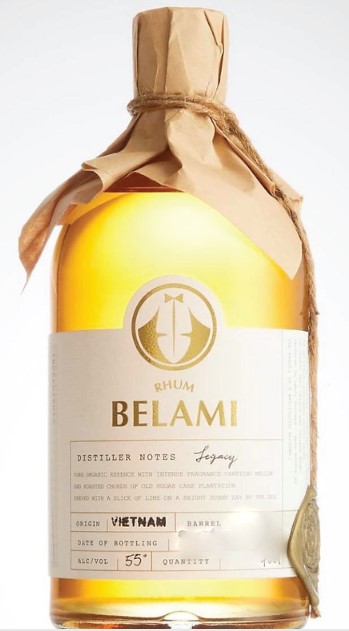

This is a sample review I’ve been sitting on for quite a while, and after trying it was never entirely certain I wanted to write about at all: but perhaps it’s best to get it out there so people can get a feel for the thing. It’s a rhum made in Vietnam since 2017 by a three-person outfit founded by an expatriate Martinique native named Roddy Battajon and occasionally turns up in social media feeds and in French and regional magazines — but, like other Vietnam rum brands we’ve looked at before (Mia, L’Arrangé Dosai and Sampan so far), lacks exposure and a more international presence. It’s the usual issue: too small for sufficient revenues to allow for rum festival attendance and a distribution deal, and the pandemic certainly did not help. Since 2022 they’ve entered into some partnership deals, however, so there is hope for a greater footprint in the years to come – for now the primary market for its rhums seems to remain regional, with some being for sale in France.

Mr. Battajon has been in Vietnam since around 2016, arriving with ten years of F&B experience in Europe under his belt, and after knocking around the bar circuit there for a while, felt that the high quality of local sugar cane and the mediocre local rhums (the most popular is called Chauvet, and there are bathtub moonshines called “scorpion” and “snake wine” which one drinks just to say one has) left a space for something more premium. He linked up with a Vietnamese partner who doubles up as General Manager in charge of procurement and product sourcing (bottles, labels, corks, cane juice, spares…), and an Amsterdam-based designer and communications guy. Navigating the stringent regulations, sinking his capital into a small alembic (a stainless steel pot still), bootstrapping his Caribbean heritage and tinkering the way all such micro-distillers do, he released his first cane juice rhum in early 2017 and has been quietly puttering along ever since.

The rum is made as organically as possible, sourcing pesticide-free cane from local farmers, and eschewing additives all the way – for now a “Bio” certification remains elusive since the certifying mechanism has not yet been instituted in Vietnam. However they recycle the bagasse into compost, and botanical leftovers into a sort of bitters, and have plans to use solar panels for energy going forward, as well as continuing to source organic cane wherever they can find it.

This then, finally brings us to the rhum itself. So: cane juice, pot-still distilled from that little alembic (have not been able to establish the size or makeup), and bottled at a muscular 55% ABV. Mr. Battajon makes it clear in a 2017 interview, without stating it explicitly, that his vision of rhum is one of infusion and flavouring, not the “pure” one currently in vogue, though he is careful to make a distinction between what he does and a “rhum arrangé”. The company now makes several different lightly aged products but I have not seen anything to suggest that either an unaged white is available (yet) or that if it is, it is unadded-to.

In various articles, listings and comments online, mention is made of coffee beans, pineapple, mangoes, other fruits, and various herbs, barks and spices being added to the ageing barrels. I had no idea this was the case when I tried it – it was a sample from Reuben Virasami, a fellow Guyanese and bartender who spent some time in Vietnam and who now resides in Toronto – and he didn’t provide any info to go along with it, so I gave it the same run-through that all rhums receive. In other words, I treated it as a straightforward product.

What the Legacy did, when I tried it, was transport me back to a corner of my mind inhabited by the Cuban Guayabita del Pinar. It had that same sense of sweetly intense fruitiness about it – the nose was rich with ripe, dripping pineapples, soft and squishy mangoes, some sugar cane sap, and a few spices too subtle to make out – cinnamon and maybe nutmeg, I’d hazard. 55% makes the arrival quite powerful, even overpowering, so care should be taking to avoid a nasal blowout – fortunately it’s not sharp or stabbing at all, just thick.

What the Legacy did, when I tried it, was transport me back to a corner of my mind inhabited by the Cuban Guayabita del Pinar. It had that same sense of sweetly intense fruitiness about it – the nose was rich with ripe, dripping pineapples, soft and squishy mangoes, some sugar cane sap, and a few spices too subtle to make out – cinnamon and maybe nutmeg, I’d hazard. 55% makes the arrival quite powerful, even overpowering, so care should be taking to avoid a nasal blowout – fortunately it’s not sharp or stabbing at all, just thick.

The palate is much more interesting because some of the sweet fruit intensity is tamped down. That said, it’s not a whole lot different from the nose: pineapples, mangoes, yoghurt, a touch of breakfast spices, anise and red bell peppers, and something akin to maple syrup drizzled over hot pancakes. There’s a delicate citrus line underlying the whole thing, something crisp yet unidentifiable, with an alcoholic kick lending emphasis, but behind that, not a whole lot to go on. The finish was disappointing, to be honest, because it was short and presented nothing particularly new.

So yes, when all is said and done, the Legacy is very much along the line of the ‘Pinar except here it’s been dialled up quite a bit. Overall, it’s too sweet for me, too cloying, and you must understand that preference of mine in case you make a purchasing decision on the basis of this review – I don’t care for infused and spiced rums or arrangés, really, unless the addition is kept at a manageable, more subtle, level, not ladled into my face with a snow shovel. Here, in spite of the extra proof points, that just wasn’t the case: I felt drenched in mango-pineapple flavours, and that strength amplified the experience to a level I was not enthusiastic about. If I want a cocktail, I’ll make one.

It would be unfair of me to score a rum of a kind I usually do not buy and don’t care for — since I don’t knowingly purchase or sample such rums, experience is thin on the ground, and then I’d be making an assessment of quality I’m not equipped to deliver. Therefore I’ll dispense with a score, just write my thoughts and comments, and leave it for others to rate when their time comes. But I’ll make this remark – if a company labels its product as a rhum without qualification (by excluding the words “spiced” or “infused” or “arrangé”) then it’s asking for it to be judged alongside others that are deemed more real, more genuine. That leaves the door open to a lot of criticism, no matter how organic and well made the rhum is, and here, that’s not entirely to its advantage.

(#974)(Unscored)

Other notes

- Not sure what the origin of the company title Belami is. On the other hand the word “Legacy” is likely a call back to Mr. Battajon’s grandmother, from whom he drew inspiration.

- This Legacy edition was 55% ABV. In the various expressions, the strength varies from ~48% to ~60%

- I’ve written an email to the company asking for clarification on a few points, so this post will be amended if I get a response.

- Because several years’ worth of the Legacy were issued (some at 55%, some stronger, some weaker), I’m unsure as to the age. None state the year of make on the label as far as I can tell, but online stores sometimes make mention of the one they’re selling.