Let’s quickly run down the tasting notes for the Chamarel youthful aged expression, the VS. This is the most junior of the company’s aged pantheon – named, one would presume, after the brandy designators of VS, VSOP, XO and so on. The VS supposedly stands for “Very Superior”, but that just goes to show the French had marketing departments in their old maisons for centuries before Madison Avenue was invented, because overall, the rum didn’t exactly wow my socks off.

It smells, right off the bat, of toast — literally. Lots of toast. Also coconut shavings, vanilla, and cereals that have all at some point in their life been burnt, which I grant is amusing (and unusual) but hardly earth shattering. Anyway, this all passes, and then one can smell aromas of honey, flambeed bananas, salt caramel ice cream, nougat, toffee, white chocolate, and crushed almonds. What it’s missing is the tart and clear acidity of lighter elements and fruits, which remain very much in the background on the nose.

Palate is somewhat better, and more integrated, though quite light and there remains a sort of spicy spitefulness about the whole thing. There are tastes of nuts, wine, grapes, and cereals again. The balance is much improved, and the fruit is more forward…I keep getting this idea that there’s a splash of red wine in here too. With resting, there are additional notes of coconut shavings, bananas, more unidentifiable soft and squishy fruit: say ripe mangoes, papayas, cherries, strawberries, that kind of thing. Oh, and welcome spicy notes of cloves and cumin. All this leads to a curiously disappointing finish – it’s dusty and short, with hints of cheerios, caramel and crushed walnuts…but the fruits have once again disappeared to wherever they hid while I was smelling it.

The rum as tasted was released at 42%: currently it’s gone back to a more easy sipping 40% (as advertised on its website). I think the strength is decent for what it is, because the rough edges of its youth have not been quite sanded clean yet, and it showcases a sort of jagged edge that a stronger proof might have made worse, rather than better. From what I was told at the booth where I tried it, it was based on sugar cane juice, and run through a column still (twice, hence the “double distilled” on the label), then aged for 3 years in charred American oak; this would account for the rather strong vanilla and smoky profile that characterizes the rum, but oddly for a cane juice product, rather less of the vegetal and fruity notes which one would expect from the source.

Chamarel on Mauritius has been around for a long time, and I’ve written about it in both the Premium Classic White, the double distilled white and Velier’s Indian Ocean Sills selection reviews, so if this piques your interest and you want to know more about them, check out those reviews or their own website. I’ve not tried very many of their aged rums – because there really aren’t that may: remember, rum making was legalized on Mauritius relatively recently so it’s not as if a whole bunch of aged stocks exist on the island. So, I started with this one, the youngest, which I didn’t think was all that hot. It was a competent product, but I’m left somewhat confused what it’s meant for – it’s not good enough to sip, while lacking any serious punch over and above the vanilla, coconut and caramel, which would wake up a cocktail. Unless such a placid profile is your thing, you may want to see if you can lay hands on their older expressions, a millesime or anything they issue at a greater strength. Otherwise, be prepared by a restless sense of unfulfilled potential with this one.

(#808)(78/100)

Other

- The rum isn’t bad, just feels unfinished. As proof of its potential, note that it won a gold medal in its category at the 2018 German Rum Fest in Berlin, with other honours in the Agricole Gold class going to Clement Rhum Vieux Select Barrel (Martinique, 40%) and Saint James Ambre (Martinique, 40%)

La Rhumerie de Chamarel, that Mauritius outfit we last saw when I reviewed their 44% pot-still white, doesn’t sit on its laurels with a self satisfied smirk and think it has achieved something. Not at all. In point of fact it has a couple more whites, both cane juice derived and distilled on their

La Rhumerie de Chamarel, that Mauritius outfit we last saw when I reviewed their 44% pot-still white, doesn’t sit on its laurels with a self satisfied smirk and think it has achieved something. Not at all. In point of fact it has a couple more whites, both cane juice derived and distilled on their

Personally I have a thing for pot still hooch – they tend to have more oomph, more get-up-and-go, more pizzazz, better tastes. There’s more character in them, and they cheerfully exude a kind of muscular, addled taste-set that is usually entertaining and often off the scale. The Jamaicans and Guyanese have shown what can be done when you take that to the extreme. But on the other side of the world there’s this little number coming off a small column, and I have to say, I liked it even more than its pot still sibling, which may be the extra proof or the still itself, who knows.

Personally I have a thing for pot still hooch – they tend to have more oomph, more get-up-and-go, more pizzazz, better tastes. There’s more character in them, and they cheerfully exude a kind of muscular, addled taste-set that is usually entertaining and often off the scale. The Jamaicans and Guyanese have shown what can be done when you take that to the extreme. But on the other side of the world there’s this little number coming off a small column, and I have to say, I liked it even more than its pot still sibling, which may be the extra proof or the still itself, who knows.

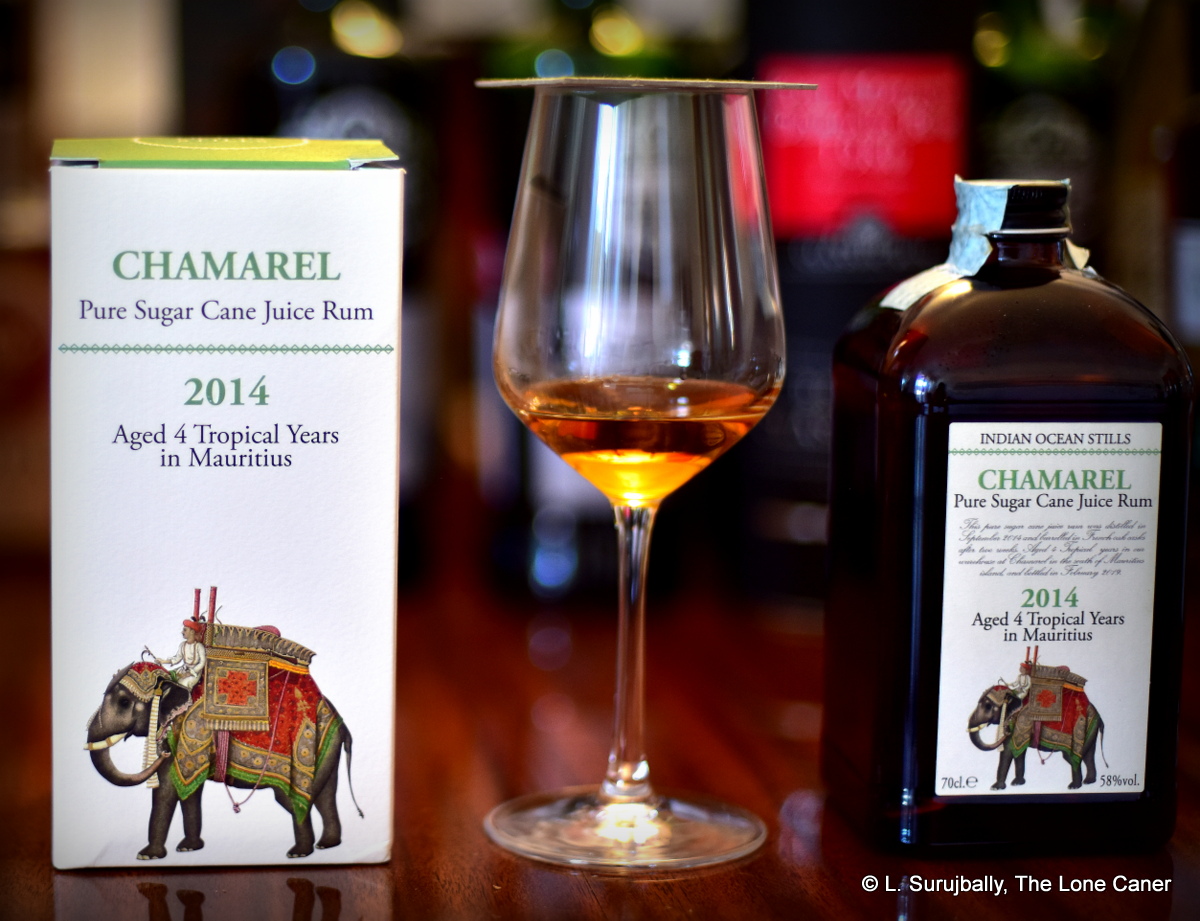

Brief stats: a 4 year old rum distilled in September 2014, aged in situ in French oak casks and bottled in February 2019 at a strength of 58% ABV. Love the labelling and it’s sure to be a fascinating experience not just because of the selection by Velier, or its location (we have tried few rums from there though those

Brief stats: a 4 year old rum distilled in September 2014, aged in situ in French oak casks and bottled in February 2019 at a strength of 58% ABV. Love the labelling and it’s sure to be a fascinating experience not just because of the selection by Velier, or its location (we have tried few rums from there though those