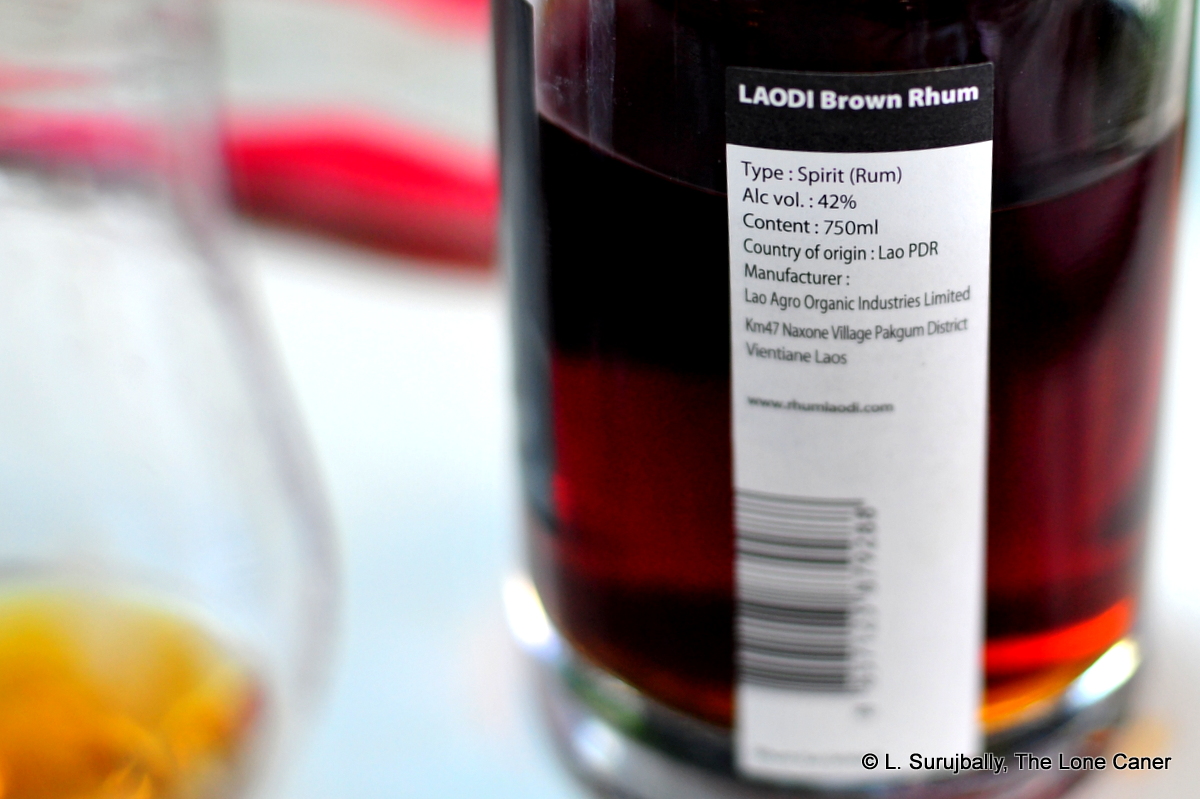

Let me run you past the tasting notes of this lower-proofed, higher-aged companion rum to the Laodi White I wrote about last time. It was an amber-coloured 42% which was aged, according to the rep at the 2019 rhumfest in Paris, for 5 years in French oak…so it seemed like it would be relatively tame and mild, taking into account the milquetoast strength and a barely-enough aging regimen (at least, compared to its unaged 56% blanc bro’).

But it wasn’t. To begin with, the nose – well, that was quite a nose, a Cyrano de Bergerac of rum noses. It was big, it was odd, it was startling and overall rather impossible to ignore. It smelled of old bookcases and old books in a disused manor-house library, of glue holding tattered paper together, of dark furniture and its varnish, and of a gone-to-seed aristocrat smoking an aromatic cigar while wearing a pair of brand new leather brogues still reeking of polish. It was a rum that was so peculiar that it encouraged equally peculiar phrasing just to describe it properly…at least at the inception. And after a while it did settle down to somewhat more traditional notes, and then we got a basketful of dark, ripe fruits – prunes, plums and apricots set off by the brighter and chirpier red currants and pomegranates, behind which lurked a faint aroma of coffee and unsweetened chocolate and a very pleasant nutty hint.

It smelled light and delicate, and dark and heavy, all at the same time, and one could only wonder what the thing could possibly taste like after such an entrance. “Flavourful” is one word that could be used without apology. The dustiness of age receded into memory and a nicely solid rum emerged and snapped into focus. It tasted of caramel, toffee, blancmange, white chocolate, almonds, coffee, vanilla, breakfast spices, cinnamon – all the expected hits, I guess you could say. But it took a step up once the fruits come marching in, because then there was a balanced offset of tart fruits to the firm and thick tastes that came before: prunes and plums, as well as guavas, overripe mangoes, peaches in syrup, green peas (not a fruit, I know) – and a much stronger shading of coffee grounds, as if this thing was channelling Dictador or something. It never quit went went away, that coffee taste, even on the finish, which was well balanced but far too short, ending with a final exhale, a last shuddering sigh, of fruit and caramel and vanilla, and then was gone.

So, all in all, a surprisingly aromatic rum from Laodi. Just to recap very briefly, this is a Laos-located, Japanese-run distillery on the Thai border, who are perhaps more known for their flavoured low-proof “marriage” rums (coming in coffee, plum, coconut, passion fruit and sugar cane varieties); they use a vaccuum-distillation machine to produce a rhum from cane juice at 47% or so and then rest it in stainless steel tanks for up to five years for the Brown rhum.

Yet they do not use actual barrels in their production process. “Ageing in oak barrels requires means that we do not have,” said Mr. Ikuzo Inoue to Damien Sagnier in a 2017 interview, and so, in an interesting departure from the norm, the company uses a different technique – it dumps French oak chips into the vat (this is also mentioned casually and without elaboration on their website) and that provides the “aged” profile, which, after all, is just the interaction between wood and spirit. By varying the amount of chips, and the amount of char they have (and so the surface area in contact with the spirit), it is therefore possible to extract a rhum at the other end which has a more intense profile than an equivalently barrel-only-aged product.

What this means is that by common parlance, the rum is not aged at all – it is infused. Moreover, the process – both distillation and infusion – means that elements of the profile deriving from oxidation and evaporation are lacking, and there is a minimal angel’s share from the steel vats. To their credit, nowhere does Laodi say that their rhum is “aged X years” and I think the terminology used by the rep in response to my questions was not meant to imply true ageing. It does raise some flags, though, because there is no real regulation of or accepted terminology for this kind of flavour enhancement / infusion / ersatz ageing process. The closest one can get is the process of using boisé in cognac, or creative enhancement often imputed to low-rent rum brands. Laodi might not have intended it, but surely this methodology will create food for thought for regulators and commentators in the years to come.

All that aside, for me as a reviewer, I have to ask, does it work? I’d say yes it does – I mean, there were a lot more flavour elements coming out of the Brown than I was expecting. I think the rhum is tasty, a bit on the weak side, too thin at the end and needs some more boosting, but a pleasant cane juice spirit that tastes aged (Mr. Sagnier himself remarked that he could not tell the difference), and is more enjoyable than that age suggests it might be. The issues it raises, though, are likely to trouble rum chums long after the bottle they bought is finished and they move on to the next one.

(#626)(82/100)

Other notes

Some of the questions that occurred to me as I was writing the last paragraphs on the subject of using wood chips were:

- Does it fly in the face of the standard and accepted ways that ageing is defined? (the rum does, after all, rest for the requisite number of years in a vat, according to Laodi).

- Will it be derided and decried by those who adhere to a more traditional way of ageing rum and consider it a form of cheating?

- How many chips are considered the equivalent of one barrel’s surface contact area? How big do they have to be? And, if you want to go to the extreme, why not just use boise or wood powder

- Is there a limit?

- Is it forbidden in any way? Is it legal?

I’m not sure. No standard I’ve read addresses any of these issues, not really. Before the sugar and additives debate took over, it was often mentioned (or accusations were made) that extra wood chips were added to barrels of some rums to make the flavour more intense, but this gradually fell out of public consciousness in favour of dosing, additives and wet barrels. I believe that at bottom, ageing can be defined as the complex interaction of wood and spirit over time, and whether the wood is on the outside (barrels) or the inside (chips) can be seen as a matter of terminology, semantics and fine parsing of regulations by the pedants.

But that obscures the fact that a barrel is a barrel, of known and uniform size and internal surface area, a common and well-understood standard used the world around for centuries. Wooden chips or sticks are a totally different thing, and adding an undisclosed amount of chips to an inert vessel just doesn’t seem to be the same, somehow, especially since there are no standards governing how they are, or can be, used.