It is a little known fact that in the 1800s, several small families whose names were to become intertwined with the history of unknown, unspeakable and unmentionable rum, started to arrive in what was then British Guiana.

The Heisens may have been the first; and from this line descended the Heisenberg Distillery, as well as the all but disappeared Alban estate run by a branch of the family begun by Grogger Heisen, later to become the Banban marque; and coiling among them all were the Fagnants, illegitimate, piratical rum makers of ill-repute who claimed without justification or evidence, to be the only descendants of Pere Labatt.

For various reasons having little to do with common sense, and mostly lost to history, these families were both connected and at loggerheads almost from the beginning, but were united (if the term can be used) in their ability to make the worst rums in the colony. This not-quite-masterwork of historical revisionism with no relation to persons living, dead or undead, is the first in a series of histories to deal with the near mythical estates and their output.

(Note: Copyright information for all photos is contained at the end).

***

The small Heisenberg family was a very old — if insignificant — one in Germany, descending from the Junkers of what was once Prussia (no relation to Werner Heisenberg). The now nearly-extinct family branch in Guyana trace their ancestry from Count Drinkel van Rumski zum Smirnoff, a member of the minor nobility who fell on hard times in the 19th century, largely as a result of excessive gambling debts and recurring bouts of syphilis arising from his predisposition to frequent houses of ill repute. Although well educated in chemistry in Russia (legend has it he once threw up a half digested bratwurst on Mendeleev’s chessboard, which gave that famous man the idea for a periodic table after observing the patterns of the spew), he did not spend long there, and returned to Prussia to continue his life of hedonism and debauchery. Finally ending up close to bankruptcy, he started to distill his own home made vershnitt in his bathtub for sale to the local peasantry; unfortunately, the bathtub was repossessed by one of his creditors, after which he began using a chamberpot to produce his moonshine, and sales for some reason dropped precipitously.

Facing ruin, irascible creditors and the threat of debtor’s prison, he made his way to Western Europe, stopping off in Holland where he was kicked out of the house of Herr Sheer after he was discovered hiding in a rum barrel, which he almost drank dry. Since he found himself again unwelcome, he moved on to Spain, where he irritated the locals immensely. Part of the reason they disliked him was the way he loudly and obnoxiously told them they did not know anything about making distilled spirits. A young Catalan named Facundo, who had provided him with a small attic room in Catalonia, listened to him for a few months, learned what he could – which was not much – and then, just to escape his constant demands for loans and free room and board, shipped out to Cuba and began his own little company. To the end of his life, Count Drinkel insisted that Bacardi owed him 50% royalties for every bottle they produced, though nothing ever came of it, and Facundo and his heirs steadfastly refused to admit the existence of the Count, let alone acknowledge his influence.

Foiled in his attempt to sponge off of others, Count Drinkel decided to emigrate to the New World, where he heard there were fortunes to be made and people weren’t too particular about the quality of rum they drank. He stowed away on a ship he heard was bound for Haiti (allegedly from a passer-by named Dupree Barbancourt whom he tried to pickpocket), but because he couldn’t read or understand maps, was deposited in Barbados instead, along with assorted bruises and sprains which, the captain of the “Sprightly Bugger” stated in an official report, came from accidentally falling down the gangway…thirteen times. He made his way to the parish of St. Peter on foot, and was subsequently chased out of the Cherry Tree Hill by Charles Cave, though not before making sure he relieved himself (copiously) on each one of the small mahogany trees leading up the hill, which may be one reason they have grown so well to this day. It was clear Barbados was not a place for him – word of his past, gambling debts and disregard for the niceties of personal property soon came to haunt him, and the English shipped him off in irons to their other colony, Guiana, where it was felt he could do some work of a more useful nature.

Guiana was every bit as much of a disappointment to Count Drinkel – he always insisted on the title – as were all the other places he visited, largely due to local residents’ inability to understand that he knew more than they did, was better than they were, and should be accorded not only respect and adoration, but actual room and board (for free). Guianese, whether from the plantocracy or freed slaves or Indian workers, were prepared to humour his delusions, but when it came to money that was quite another matter, and soon he found himself penniless and with no-one to gamble with, as everyone knew him to be a notorious (if ineffective) cheat at both cards and dice.

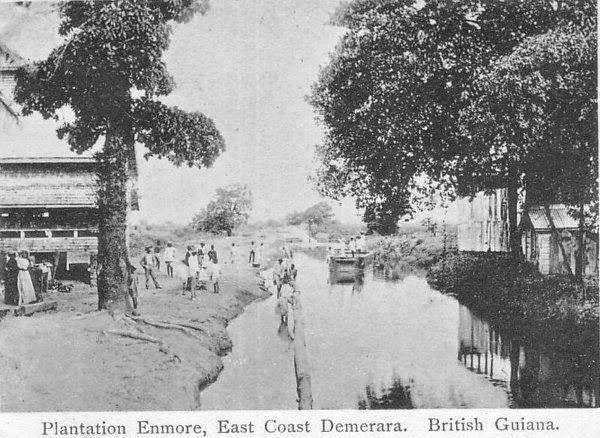

He was an odd sort of optimist, always assuming that something would turn up and that Lady Luck would one day smile on him and grant him her slippery favours. And indeed, at this point a great stroke of good fortune came calling. Griselda Verdie Delissey Heisenberg Porter, the seventh daughter of Thomas Porter who owned the Enmore plantation, was proving impossible to marry off due to some delicate inconsistencies relating to her birth, but mostly because of her poisonously acerbic character and generally slovenly appearance and indifference to personal cleanliness, which scared off all potential suitors. Being hardened to all forms of filth by years of wandering in the fleshpots of the world, this did not severely inconvenience or alarm Count Drinkel, who spruced up his only good suit of clothes (much mildewed in the tropical heat), and came courting. He won her hand by simply pointing to himself, grandly declaiming his noble heritage, and saying he wouldn’t mind. Mr. Porter had been at his wits’ end regarding his almost unacknowledged daughter, gladly acquiesced, and as a dowry deeded her and his new son-in-law, with an acre of sugar cane land way down behind his own plantation, which Mrs. Griselda van Rumski zum Smirnoff promptly and grandiosely christened “The Heisenberg Plantation”.

He was an odd sort of optimist, always assuming that something would turn up and that Lady Luck would one day smile on him and grant him her slippery favours. And indeed, at this point a great stroke of good fortune came calling. Griselda Verdie Delissey Heisenberg Porter, the seventh daughter of Thomas Porter who owned the Enmore plantation, was proving impossible to marry off due to some delicate inconsistencies relating to her birth, but mostly because of her poisonously acerbic character and generally slovenly appearance and indifference to personal cleanliness, which scared off all potential suitors. Being hardened to all forms of filth by years of wandering in the fleshpots of the world, this did not severely inconvenience or alarm Count Drinkel, who spruced up his only good suit of clothes (much mildewed in the tropical heat), and came courting. He won her hand by simply pointing to himself, grandly declaiming his noble heritage, and saying he wouldn’t mind. Mr. Porter had been at his wits’ end regarding his almost unacknowledged daughter, gladly acquiesced, and as a dowry deeded her and his new son-in-law, with an acre of sugar cane land way down behind his own plantation, which Mrs. Griselda van Rumski zum Smirnoff promptly and grandiosely christened “The Heisenberg Plantation”.

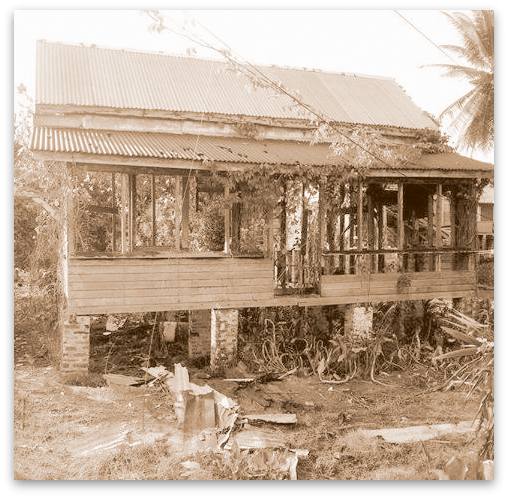

It was perhaps because he was tired of moving around; Count Drinkel settled down in a shack his father in law built, and looking around, decided there was nothing he wanted to do except drink. Since he knew a little about distilled spirits, he asked Mr. Porter for an old cast iron bathtub and some pipe, and with Griselda lending most of the muscle (she was reputed to be six feet tall and had hands the size of hams) built a leaky, farting pot still, and had enough metal left over for a condenser and cooling apparatus. For a share of the sugar cane “harvest” on his solitary acre, he got a freed slave to chop the cane and feed the manual crusher, and on average managed to make about five or six barrels of high proof white lightning a season, which, if he paced himself, was enough to keep him half drunk for the better part of the year. The barrels he appropriated from his father in law, and in a misplaced sense of generosity, used his wife’s middle initials VD as his marque. Admittedly, his English was still not very good, and the meaning of the initials escaped him, though it was doubtful he would have cared, as the entire output of his small “estate” was for personal consumption, not sale or export.

He and his wife, perhaps surprisingly, were able to survive with a mixture of appeals to Mr. Porter for support, occasional gambling bouts in the nearby villages with those too innocent to know they were being fleeced, sales of an excess barrel or two to an Indian named Jaikarran (who used it – variously, depending on need – to make bathtub cleaner or to scour passing merchant ships of barnacles, in between taking care of his pharmacy), and outright theft. When their only child Tipple Heisenberg Van Rumski Zum Smirnoff was born, the local registrar had been drinking copiously with Drinkel while Griselda was in labour, and misspelled the name, and so Tipple’s birth certificate said Tipple Heisenberg van Drunken, although for his entire life he was just known as Tipple Heisen. Tipple was a chip off the old block, a truant from an early age, enamoured of the same vices that had brought his now aged sire to ruin. After the flu carried off both his parents in 1919, he must have come to his senses, because he displayed a rudimentary sort of economic understanding, and since he drank less heavily than his father had, he had a few extra barrels of the now-renamed Heisenberg vintage to sell to passing ships or local merchants.

In this way, the lore and myth of the Heisenberg barrels began. There were never very many since the acreage was small and quality a constant variable. Tipple never managed, or never cared, to expand the estate beyond a few additional acres will to him by his grandfather, but he kept the snorting, leaky, steaming, farty pot still, and even managed to add an extra thumper keg or two to make it an ersatz creole still. He also displayed little interest as to what he added to the wash, and there were stories told in the bush years later about dead cats, discarded suits and rotten pumpkins but these were most likely the old equivalent of modern urban legends. Certainly a few barrels over the years found their way to EH Sheer’s offices, and even Cadenhead was rumoured to have bought one. Some say that Gordon & MacPhail doctored its Jamaican 1941 58 year old with a few ounces of Heisenberg distillate to give it some bite and kill the floating rats, but there is no evidence for this at all.

A perusal of records of the local parish shows that Tipple Heisen Van Drunken eventually married a solid, no-nonsense shopkeeper’s daughter named Doris Berg. Doris was big, Doris was tough, Doris was smart, and Doris took absolutely no crap from anyone. She immediately declared that she would never give up her own name, and preferred the double-barrelled appellation of Drunken-Berg, to which Tipple, after some epic battles, finally agreed, more out of exhaustion than any kind of conviction. The small family continued to eke out a living on the few tiny acres, one of which Doris converted to a vegetable garden – she sold produce in the area’s market when she could – but the mainstay of the Drunken-Berg finances remained the little still which regular as clockwork produced ten to twenty barrels a year. In short order, “Miz Dahris” (as she was known by neighbors) squeezed out four children, the daughters Ella, Bella and Stella, who married and moved away and are (almost) lost to this story, and a son.

Chugger van Drunkenberg was born in 1940 – by now the family name had lost the hyphen, and the “zum Smirnoff” and “Heisenberg” had been forgotten except for some old stories regarding the name on the barrels under which their rum was marketed. Chugger, also known as “Chigoes” after the foot eating worm, was never very literate, but a good businessman. He was also not a drinker, and that meant the full output of the little still was available for sale. Most of the time Chugger just sent his stock up the road or down the river to Enmore and it got lumped in with his great-grandfather’s own distillate. But as the fifties gave way to the sixties in British Guiana, the British firms consolidated the estates from their original owners, and it was not always possible to sell the rum he made, just the cane itself. Chugger van Drunkenberg’s initial good fortune didn’t vanish overnight, just dribbled away over the years as there was less and less cane for him to sell, and the Heisenberg name became less and less well known, eventually all but vanishing.

Most people, of course, were never aware of the tiny distillery, largely because they rarely bottled anything themselves, only sold whole barrels; too the rum was so pungent, so ferociously strong and increasingly bizarre in taste (with wide variations from one barrel to the next), that few had the courage to buy it. It was variously described as “dark”, “hellish”, “industrial strength solvent,” “more rotting fruits than a near-bankrupt grocery store”, “something that gives dunder a bad name”, “fit only for cleaning rust from mothballed oil refineries,” and “redolent of Admiral Bimbo’s sweaty armpit at noon” (said Admiral sharing said characteristic with his less-ranked son, or so rumour had it). No wonder those few who came across it avoided it like the plague.

Even Lamb’s refused after the 1950s to accept any more for their Navy rum, and the loss of the relatively consistent sales to that company meant Chugger had to fight to sell even what he could. It never seemed to occur to him to standardize his production, or even modernize – in that, he had the laissez-faire attitude of his grandfather, whose attitude to life was summed up by the phrase “Something will turn up.” And a trickle of Heisenberg estate rums did in fact make it out to independent bottlers from time to time: E.H. Keeling might have bought a barrel or two, it was rumoured to be a part of Russian Bear rum (sold mostly in-country), a few far sighted Italians did buy some. But the trail mostly ends there, and Chugger never bothered to dig deeper into the matter – once the sale was made, he was happy. He didn’t tolerate people much, and once chased a young man called Yesu Persaud off his property with a cutlass for the crime of setting half a foot and two toes on his land.

It was therefore somewhat of a surprise when people heard that he got married, in late 1966. Perhaps married is the wrong term – he got a local Amerindian lass called “Tanti” in a family way and she simply moved in, and less than half a year later, she provided him with his only son, whom he named Ruminsky. Ruminsky’s fate in life was supposed to be to take over the small patch of land (which he was unaware had come through from a great-great grandfather). Being a bright and precocious boy with absolutely zero interest in rum or sugar or hard work of any kind, he elected to leave Chugger and Tanti to run the tiny business while he went to school. The Heisenberg distillery lurched on until 1973, though Black Tot Day three years earlier effectively wiped them out, and then it shuttered for good. The final barrel ever made, stamped “Heisenberg 1973,” was bought by an Italian, who was then refused an export license by the Government of the day (by the time he submitted his final batch of papers for the application, the first ones had expired) and so after a year of futile chasing after paperwork, he simply left, selling his various barrels of acquired rum stock from Skeldon, Port Mourant and Heisenberg to Bookers, the fore-runner of the modern DDL. Bookers just rolled them into their facility and left them there to age. With the gradual consolidation of sugar estates under the DDL banner, all these barrels lay gathering increasing dust…and it was not until another enterprising young Italian from Genoa called Luca Gargano walked into the warehouse, that they were rediscovered.

The PM 1972 and 1974, and the Skeldon 1973 were hailed by many as masterpieces, and nowadays fetch many times their original asking price. But Luca didn’t know what to make of that one almost-corroded barrel from distillery neither he nor DDL had ever heard of, a small patch of ground now closed and left to grow over by the encroaching jungle. Chugger and Tanti had moved to New Amsterdam, Ruminsky stayed in school in Georgetown, the distillery apparatus had been vandalized and stolen bit by bit, and there was nobody around to speak of the all-but forgotten little outfit run by three generations of Drunkenbergs and Van-Rumski-Zum-Smirnoffs except for some rice farmers and sugar workers, a closed mouthed lot who would chase people off their land with no compunction, and Luca was never able to penetrate their country-bred clannishness. So he took his barrel to Italy (he was better at paperwork than his predecessor) and chucked it into his office.

Enter a young, ambitious and light-fingered aspiring rum-maker called Caputo, who liked to say he was the illegitimate son of D.B. Cooper, that masked bandit who jumped out of a plane in 1972 after hijacking it and collecting a ransom of $200,000. Young Caputo worked as an office boy for Velier in Genoa, and saw the barrel, and, sniffing an opportunity, didn’t waste his breath trying to buy it – he lacked any semblance of legal tender in his threadbare pockets anyway. He simply waited for the maître to go on one of his trips abroad, and then calmly rolled it out of the office, into the street, and down to the seedy garage where he lived in the back of a flower-power-era 1960s VW van. Shortly thereafter he left Genoa and took the barrel with him. There are no reliable records to confirm the matter, of course, but what seems clear from private conversations is that this was around 2010 or thereabouts.

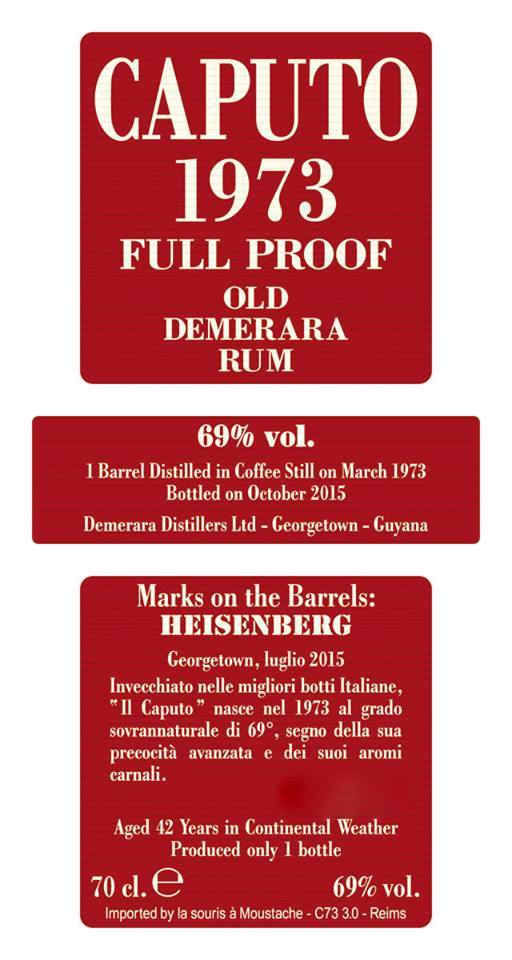

Much to his frustration he found the barrel impossible to sell. Nobody had ever heard of Heisenberg, there was no paperwork proving the provenance of the rum in his possession, and so in 2015, at a loose end and with even less money available than usual, he decided to finally give up, and just bottle what was left in the barrel. Unfortunately, after some 42 years of sloshing around, there was almost nothing left, but with a teaspoon and a dish-washing sponge, he managed to scrape out one single bottle, and remembering his experience with Velier, copied their label, ran it off on his printer and slapped it on. By this time the resurgence of rum in the world, and reviewers who swore by old vintages, as well as the ubiquity of eBay, made it possible to bypass normal channels of distribution, and he put it up for sale there.

Much to his frustration he found the barrel impossible to sell. Nobody had ever heard of Heisenberg, there was no paperwork proving the provenance of the rum in his possession, and so in 2015, at a loose end and with even less money available than usual, he decided to finally give up, and just bottle what was left in the barrel. Unfortunately, after some 42 years of sloshing around, there was almost nothing left, but with a teaspoon and a dish-washing sponge, he managed to scrape out one single bottle, and remembering his experience with Velier, copied their label, ran it off on his printer and slapped it on. By this time the resurgence of rum in the world, and reviewers who swore by old vintages, as well as the ubiquity of eBay, made it possible to bypass normal channels of distribution, and he put it up for sale there.

The response was instant and gratifying. He had set a reserve of a few hundred euros on it, but to his amazement bidding began to get quite fierce, and it climbed past a thousand euros in very short order, before some jealous and malicious blogger who had been outbid called into question the existence of the rum. Obviously, since there was only one bottle in existence, it was impossible to send samples around, so the poor Mr. Caputo, stymied, was forced to remove the listing. It appeared that nobody had ever heard of, or was willing to take a chance on, a remarkably rare old rum from an estate that history had relegated to less than a footnote.

Except one.

Chugger and Tanti van Drunkenberg had long since gone to the great distillery up in the sky, but their son Ruminsky did survive, and after some promising beginnings in the accounting world, he exhibited many of the traits of his ne’er-do-well ancestor, having a strong and excessive fondness for the baser pleasures of mankind, namely gambling, rum and girls, even if he did so with more good cheer and a sort of charming optimism lacking in his forebears. This was one reason why he never became rich, and was always off to some other crazy part of the world where he felt he could indulge his obscure interests. He also had something of a literary bent, and in 2010 began a small rum-review site that nobody ever cared about or ever bothered to read (a state of affairs that persists to this day). Not for him the effort of actually making rum, let alone running a distillery, or (heaven forbid) cutting cane – that might get his soft hands dirty, or, even worse, cause him to sweat. He was a cheerfully failed artist, if not quite starving, and ambled through life with a sunny good humour that reprised his ancestor’s maxim that something would turn up.

And indeed it did. When he heard through the miracles of modern social media that a single bottle of his forebears’ rum was still in existence, he contacted the now near-desperate Caputo, and offered him half the last bid on eBay, sight unseen. Caputo, who would have let it go for one tenth that price , happily grasped the straw that was being given, and sold it on the spot. Ruminsky, in October of 2016, displaying more optimism than any kind of good sense, made the mistake of letting some his fellow bloggers, all better known and more successful than he was, know that he had the bottle.

There was instant pandemonium as the news flashed around the world as quickly as you could say “Only one bottle”. Velier called from Italy to demand their bottle back, Rum Nation offered to buy it, Florent Beuchet of CDI came calling in person offering his entire Danish Collection in exchange, and museums from around the world, alerted to the bottle’s reality, also offered to take it off his hands (for free) as a precious resource. Carl Kanto reputedly burst into tears, and Yesu Persaud, now in retirement, claimed that Ruminsky’s father Chugger had been an idiot who didn’t know the first thing about rum, before suggesting it be given to DDL’s Heritage Centre. The stampede of European bloggers to Ruminsky’s tiny walk-up in Germany was so uncontrolled that Berlin police had to set up a cordon around the place to direct traffic. Every one of them (the bloggers, not the police) demanded a sample to take away to write about, as well as “Just one shot for the road, friend,” and intimidated by their wild-eyed, rabid enthusiasm, Ruminsky timorously complied, at which point everyone left – running – almost as quickly as they had appeared. Everyone wanted to be the first to put up a review of the legendary Heisenberg Rum.

The reviews that will be posted online are a result of that bottle’s “sharing.” Few recall Count Drinkel van Rumski zum Smirnoff who started it all, fewer know his name or that of Tipple and Chugger. All but one of the family are now gone. Ruminsky has retreated into the obscurity from which he emerged for his fifteen minutes of fame. His site remains perennially unread. He remains stubbornly cheerful. “The rum is finished; only words remain,” he said once in an interview with this writer. “But I’ve heard there may be another barrel hiding out in the world somewhere. Maybe I’ll find it.” He shrugs, smiles…and for a moment, just a moment, the Old Count looks through his eyes. “After all, sooner or later, something always turns up, right?”

Yes. Yes, it does.

- The first (and only) review of the Caputo 1973 rum is here.

Other Notes

Many thanks to the wicked sense of humour of Signore Caputo, whose sterling efforts resulted in this essay. If you can believe it, it was written in less than six hours, at a white heat of rum and bad jokes and batsh*t crazy inspiration. And it’s all due to him.

Copyrights and sources of photos:

- Enmore Plantation photo taken from Barrel-Aged-Mind

- Heisenberg family house, the barrel and the lady at the market (none of which are exactly what is stated in the captions) taken from the excellent FB archive page called “British Guiana / Guyana”. Since they are old, often family pictures there, I can only attribute it to the FB site and not to individuals. Copyright should be implied, however.

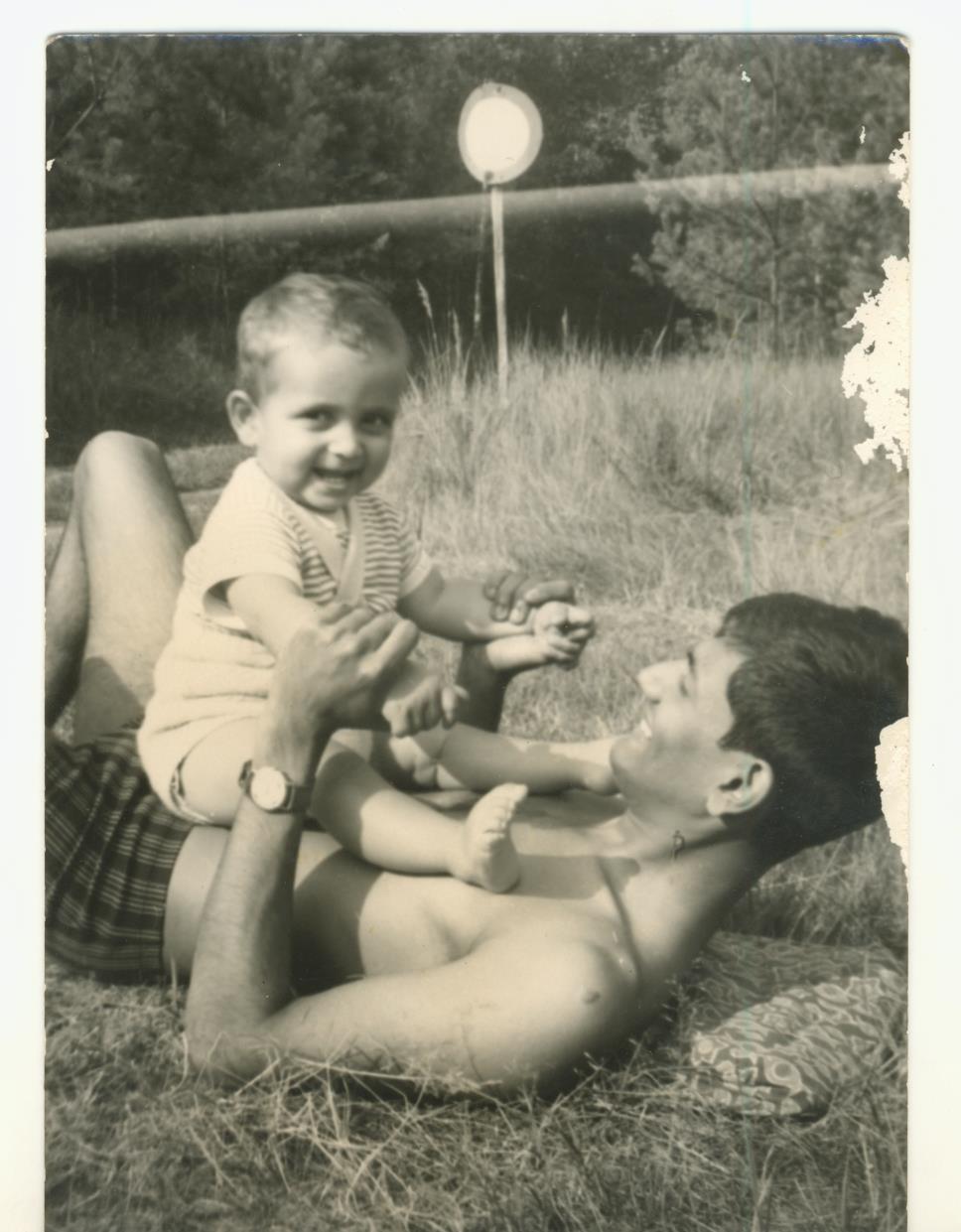

- Chugger and Ruminsky family photograph copyright (c) Lance Surujbally, The Lone Caner

- Caputo 1973 label and bottle picture courtesy of Mr. Caputo, used with permission

- Count Drinkel cartoon based on a Pinterest photo whose originator I could not find, but if identified, is copyrighted to that individual.

Hahaha…..A great read to start off the week!

No tasting notes?…disappointing 😉

Don’t worry, that’s coming …

Hilarious…:D

Awesome story. A movie ought to be made from this story starring maybe Daniel Day Lewis or even many others.