The only rum I’ve ever tried from the Seychelles was one that was discontinued, the Takamaka Bay Overproof white, but the depth of research I did on that short article was not inconsiderable, and it formed the basis of this short biography. That doesn’t mean that I’ve tried much of their rum, but fortunately that’s not a prerequisite for inclusion in the Makers series of essays.

Given how much press the Indian Ocean islands of Mauritius and Reunion gets these days, what with New Grove, St Aubin, Savanna, Isautier and Rivière du Mat distilleries putting cool rums out the door, Seychelles remains somewhat overlooked. Yet they too have a long history of local rum production, though as of this writing, there is only one distillery on the island, and that’s the Trois Frères Distillery (who make the Takamaka brand of rums), on the main island of Mahé. This distillery is of relatively recent vintage, being formed in 2002 by the d’Offay brothers, Richard and Bernard (although there are three of them, hence the name), together with their father Robert d’Offay.

Seychelles is considered to be part of Africa; the earliest recorded sighting by Europeans took place in 1502 by the Portuguese Admiral Vasco da Gama, with the earliest recorded landing in 1609 by the crew of the “Ascension” under Captain Alexander Sharpeigh during a voyage for the British East India Company. The islands became a transit point for trade between Africa and Asia and even a haven for pirates. In 1756 the French staked their claim, and named them after Jean Moreau de Séchelles, Louis XV’s Minister of Finance. By the 1790s the British took over during the Napoleonic Wars, with full control ceded to them by France upon the surrender of Mauritius in 1810, formalised in 1814 at the Treaty of Paris. The Seychelles became a crown colony separate from Mauritius in 1903 and gained independence from Britain in 1976.

Rum was first introduced to the Seychelles in the mid 16th century by the British Navy, with actual cultivation only becoming common in the late 1800s, primarily to supplement the sugar brought in by (infrequent) ships. Unsurprisingly, a local market in fermented cane juice called baka developed out of this, which were the beginnings of grass roots rum production on primitive backyard stills. Mostly this tended to be rhum arrangé – a mixture of local rum and a blend of herbs and spices (cinnamon, dried fruit skins, vanilla etc), with each family having its own variation.

The Trois Frères Distillery was founded in 2002 and was originally located in Providence, an industrial area in the north east of Mahé. Richard and Bernard d’Offay are both native Seychellois who spent their childhood in South Africa before returning to Mahé in their mid-twenties with the intention of making rums. Initially they were a tiny two-man company, tinkering with the process and brands and marketing, but very much a niche operation. Their associations with rum were older than that, though: their grandfather had endlessly experimented with his small still and various spices (caramel, vanilla), and it could be said that all the two brothers did was formalize the enterprise by incorporating it.

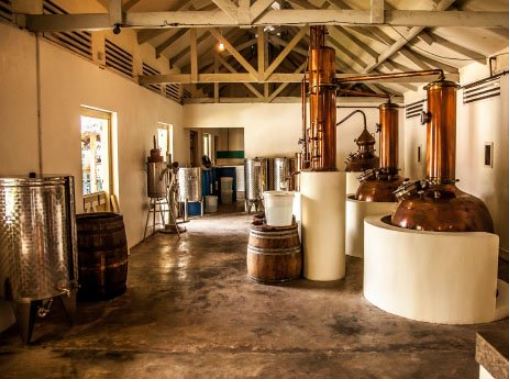

The company remained small, producing no more than 2000-3000 cases a year, almost all of it being sold locally; exports, such as they were, grew slowly. As many small countries with a colonial past have found, locals saw imported stuff as good and locally made as somehow less, an attitude that persists to this day (and not just in the Seychelles). But after eight years of incremental progress, they were successful enough and reputable enough to put in a bid to operate La Plaine St. Andre (a national heritage site; it was once a spice plantation dating back to the 1700s but had fallen into disrepair and almost completely destroyed by fire in 1990). The d’Offay family was granted a 50-year lease for the property in the south east of Mahé, and they restored it over a period of two and half years in order to set up the distillery there (the restored La Grande Maison is open to the public).

Photo (c) GotRum magazine

Oddly for a distillery, they don’t grow their own sugar cane – the lack of flat land on Mahé precluded the development of large plantations; instead, they source it from a farmer’s cooperative representing several dozen cane famers on Mahé – some with as few as 200m² of land – and anywhere between one to three tonnes of cane is delivered twice a week. The crushing provides the cane juice which is poured into fermentation tanks, where it stays for a maximum of five days — they use their own yeast for this, not “wild”. Then it gets run through either their pot or column stills – the first pass gives a distillate between 50-60%, it’s run through a second time, and then a third, resulting in a 94% final distillate, which is then transferred to a steel tank for twelve weeks, before being poured into various American oak barrels for ageing. Some of course is drawn off and diluted to 69% ABV for the blanc, to which is added some high ester pot still distillate for kick. Takamaka has a cask management program using some 23 or so different cask styles (port, sherry, bourbon, 1st fill, 2nd fill, toasted etc) except for their cane juice rhums which use almost 100% French oak.

By 2013 the company was successful enough to begin targeting the export market more seriously, as the feedback from tourists to the island (and that of the minimal exports they had made to that point) was quite positive. They retained a London based branding agency to revamp the Takamaka Bay rums’ labels and bottle designs (previously done in-house by Richard’s brother-in-law), because they knew that presentation sells, and the international rum market was rife with brands possessing centuries old street cred which represented formidable competition for a young company such as theirs. By 2015 they were sending their rums to Europe (mostly to the UK and Germany – the latter distributes to the German, Swiss, Austrian and Dutch markets), but also to the UAE, China, Mauritius, Madagascar, the Maldives, South Africa and Djibouti.

Photo (c) Seychelles News Agency

While by 2015 the company had ramped up production to 40,000 cases of rum annually, they continued to face challenges, many imposed by the Seychelles’ relatively remote location. All raw materials – bottles, caps, labels, boxes – are imported and scheduled carefully. David Boullé, the head distiller of Takamaka Bay (he’s a cousin, and joined them in 2005), remarked in a 2016 interview with GotRum magazine that “The limited amount of sugarcane available is probably our greatest constraint to rum production. There is a law in Seychelles that no sugarcane can be grown on land that can be used for food crops, thus there is a limit to the amount of cane land available.” However they do carry out an outreach program to provide a free consultation process for anyone wanting information on sugarcane cultivation, and slowly there are more local farmers who are planting small plots of cane as way of earning some extra cash.

The company had also considered using molasses instead of juice to produce its rums, but costs were prohibitive and supply sporadic; there is some supplement to regular production with molasses based distillate, however, which makes the rums that do have such hybridization rather similar to Guadeloupe’s non-AOC rums. They are careful not to call their rums agricoles both for this reason, and because in the EU, a major market, the word is restricted to rum production from the French Caribbean islands, Madeira and Reunion; also, TB’s fermentation, distillation and aging methods are different, so they opted not to use the term at all.

The global downturn in 2020-2021 caused by COVID was a boon to many distillers, who saw their sales skyrocket. Emboldened by their larger sales and global recognition, Takamaka invested in a new state-of-the-art 200,000-liter capacity distillation apparatus (it is meant to process mostly molasses) as well as two new pot stills, which are all slated to go on-line and operational in late 2021. The company’s stated goal is to increase exports to fifty countries in the next five years

Takamaka, then, even after nearly two decades of gradually increased production, continues to be a relatively unknown company in the larger rum consciousness (outside the few countries where it’s sold). It’s rarely, if ever mentioned on social media. Their stable of branded bottlings remains small. Yet, those few who have tried their work tend to be positive about it, so there’s definitely potential there. The local market is still a major source of revenue, and one hopes that the expanded distillation facilities will make a large splash on the festival circuit around Europe or North America, and their exports around the world do in fact increase commensurately.

However, as noted above, they do labour under the restriction of resource scarcity so there is an upper limit to how much rum they can produce at a margin that allows coverage of operating costs and continual re-investment, development and increased output, while retaining the unique profile and characteristics of terroire that the Seychelles can capitalize on. I think that sooner or later they may chose to make a virtue out of the problem, not so much by increasing production as changing it, and going for the upscale boutique and high-end market where the unicorns of cask strength and/or ultra-aged rums reside. Were they to do that, I have a feeling they would become known a lot further, a lot faster and a lot more, than they are now. I wish them the best of luck.

Current Rums in Production (excludes spiced and flavoured variations)

- Seychelels series

- Takamaka Bay White Rum (43%)

- Takamaka Bay Dark Spiced Rum (43%) Based on the d’Offay family’s original formula

- Takamaka Bay Extra Noir (43%) Blend of 3YO aged sugarcane juice distillate and molasses distillate, plus caramel for colour.

- Takamaka Bay St. André Rhum Vesou (40%) White rum, a blend of cane juice and molasses distillate.

- Takamaka Bay St. André 8 year old (40%)

- Takamaka Bay 69 Rhum Blanc (69%) Replaced the 72% Overproof. It was renamed “Takamaka Overproof Rum” and dropped the word “Bay” as well as changing the label design in 2020. There are therefore three different version of this rum kicking around as of 2022.

Sources

- Wikipedia for both the history of Seychelles and the distillery

- 2013 Drinksreport interview with Richard d’Offay

- 2014 Seychelles News Agency article on the company

- 2016 GotRum interview with David Boullé

- Company wesbite and its associated blog

- 2021 Spirits Business interview

- Various online shops with a snippet here or there on the various Takamaka rums they sell.

- My requests to Takamaka for more background information went unanswered after a week, so I went ahead and published.

- 2021 update by Drinks International