What is there to say about either Velier or Caroni, that hasn’t been said so many times before?

What is there to say about either Velier or Caroni, that hasn’t been said so many times before?

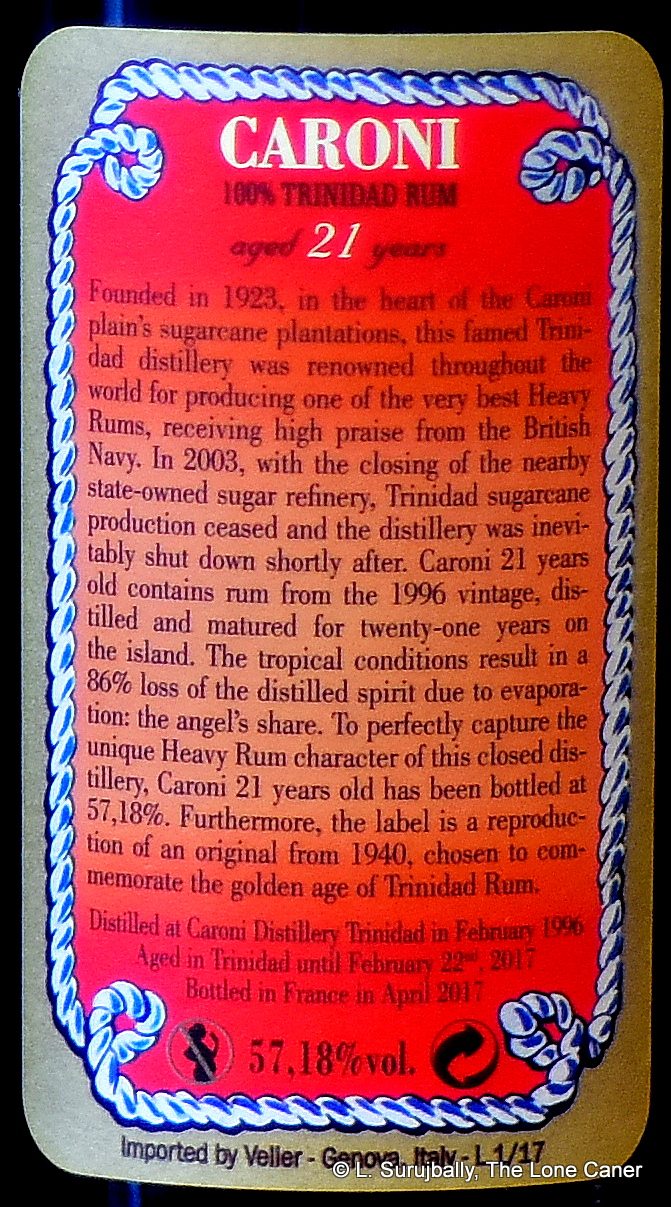

It seems almost superfluous to repeat the story but for the sake of those new to the saga, here’s the basics: Caroni was a Trinidadian sugar factory and distillery which, after many ups and downs related to the vicissitudes of the sugar industry, finally closed in 2003. In late 2004 Luca Gargano, the boss of Velier, came upon and subsequently bought, many hundreds (if not thousands) of barrels that had been destined for auctioning or fire sale disposal (for the sake of completeness, note that many others did too).

Previously, either on their own account or when managed by Tate & Lyle (a British concern which operated the establishment for many years), Caroni had made rums of their own, but they were considered low quality blends and never thought to be very good. Now, however, Velier issued them in tiny lots, often single barrel releases, cask strength and quite old. Though initially sold only in Italy, by 2010 they had already acquired an underground following, with a reputation that only grew over the years – and this is why prices on secondary markets for the very first releases dating from the 1970s or 1980s can go for thousands of dollars, or pounds.

These days, with the prices and number of variations of the early Caroni rums ascending out of reach of most, the blended aged expressions may be the best value for money Veliers from the canon we can still afford, or find. What they provide for us is something of the tar and smoke and petrol portions of the profile that characterize the type, without any of the miniscule variations and peculiarities of single barrel expressions. They are, in short more approachable overall to the curious layman who wants to know what the Godawful kerfuffle is all about. Granted, many other indies have gotten on the bandwagon with their own Caronis and they are usually quite good, but you know how it is with Velier’s cachet and their knack of picking out good barrels even when making blends.

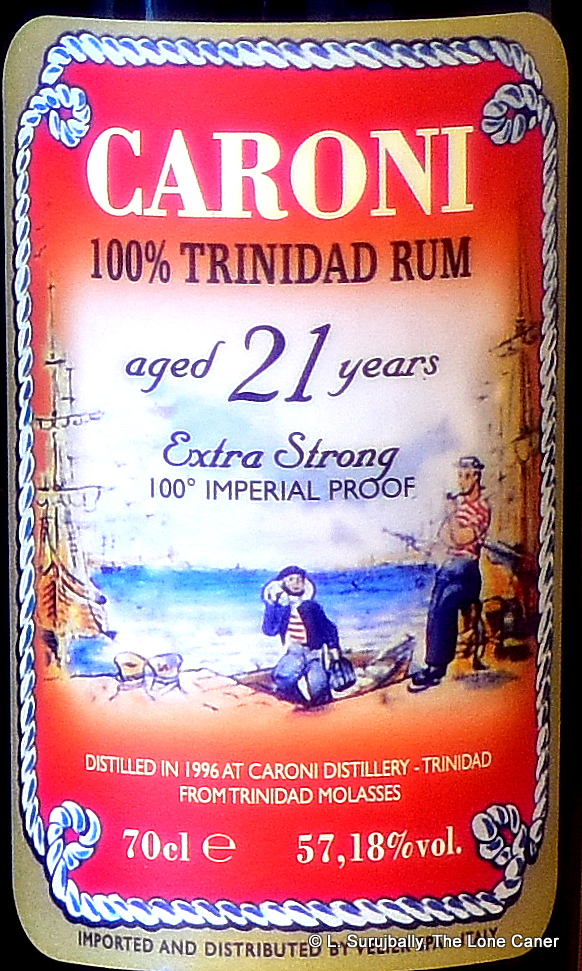

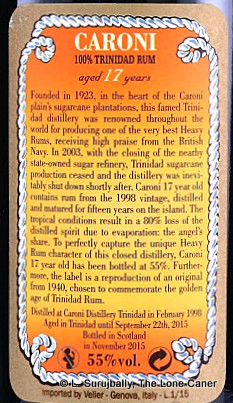

So, this one: distilled on a column in Caroni in February of 1998 and aged in situ until September 2015, when it was shipped to Scotland for blending and bottling at 55% ABV. All this is on the label, but curiously, we don’t know the total outturn. In any event it’s one of a progressively more aged series of blends – 12 YO, 15 YO, this one and 21 YO – meant for a more consumer facing market, not the exclusive Caronimaniacs out there, who endlessly dissect every minor variation as if prepping for a doctoral thesis.

Those who spring for this relatively cheaper blend hoping for a sip at the well, will likely not be disappointed. It has all the characteristics of something more exclusive, more expensive. Initial aromas are of petrol, an old machinists shop with vulcanizing shit going on in the background, rubber, phenols, iodine. Gradually fruits emerge, all dark and sullen and sulky. Plums, blackberries, dates, plus sweet caramel and molasses. Some herbs – dill, rosemary. And behind it all coils the familiar scent of fresh hot tar being laid down in the summer sun.

The taste is very similar. Like the nose, the first notes are of an old bottom-house car repair shop where the oil has soaked into the sand, and rubber tyres and inner tubes are being repaired everywhere, and the occasionally pungent raw petrol aromas makes you feel like you’re passing an oil refinery. But this is all surface: behind that is also a more solid and lasting profile of brine, olives, dates, figs, and almost overripe peaches, prunes, even some coffee grounds and anise. It’s dry, and a touch bitter, redolent of aromatic cigarillos, damp black tea leaves. Nice but also, on occasion, a little confusing. No complaints on the finish, which is reasonably long, thick, with notes of caramel, nuts, licorice and dark fruit. It’s a peculiarity of the rum that although sweetness is really not in this rum’s DNA, it kinda tastes that way.

The taste is very similar. Like the nose, the first notes are of an old bottom-house car repair shop where the oil has soaked into the sand, and rubber tyres and inner tubes are being repaired everywhere, and the occasionally pungent raw petrol aromas makes you feel like you’re passing an oil refinery. But this is all surface: behind that is also a more solid and lasting profile of brine, olives, dates, figs, and almost overripe peaches, prunes, even some coffee grounds and anise. It’s dry, and a touch bitter, redolent of aromatic cigarillos, damp black tea leaves. Nice but also, on occasion, a little confusing. No complaints on the finish, which is reasonably long, thick, with notes of caramel, nuts, licorice and dark fruit. It’s a peculiarity of the rum that although sweetness is really not in this rum’s DNA, it kinda tastes that way.

It’s been bruited around before that Caroni rums, back in the days of Ago, were failures, implying that these rums today being hailed as such classics are a function of heritage and memory alone, not real quality in the Now. Well, maybe: still, it must be also said that in a torrential race to the lees of anonymity and sameness, they do stand out, they are in their own way unique, and the public has embraced their peculiarities with enthusiasm (and their wallets).

On balance, I liked it, but not quite as much as the 21 YO in the blended series. That one was a bit better balanced, had a few extra points of elegant distinction about it, while this one is more of a goodhearted country boy without the sophistication – but you know, overall, you would not go wrong picking this one up if you could. There is nothing wrong with this one either, and it represents Caroni’s now well-know tar and petrol profile quite solidly, as well as simply being a really good rum.

(#866)(84/100)

Other Notes

- The label is a facsimile of the original Tate & Lyle Caroni rum labels from the 1940s