Among South American rums, some countries just don’t make waves outside their own borders. How many of us have heard of Gran Chaco from Bolivia, or Isla Ñ and Tickerman from Argentina, for example? In Paraguay, the source of today’s review, we’ve been fortunate once before to try the “Herocia” from the Fortin brand, and here we have another one from the distillery of origin (see below for details), brought to us courtesy of La Maison du Rhum in France – this is in turn a 2017-founded brand of the French spirits distributor Dugas, and may be the only way we’re ever going to get a rum from such a relatively obscure (in rum terms) product.

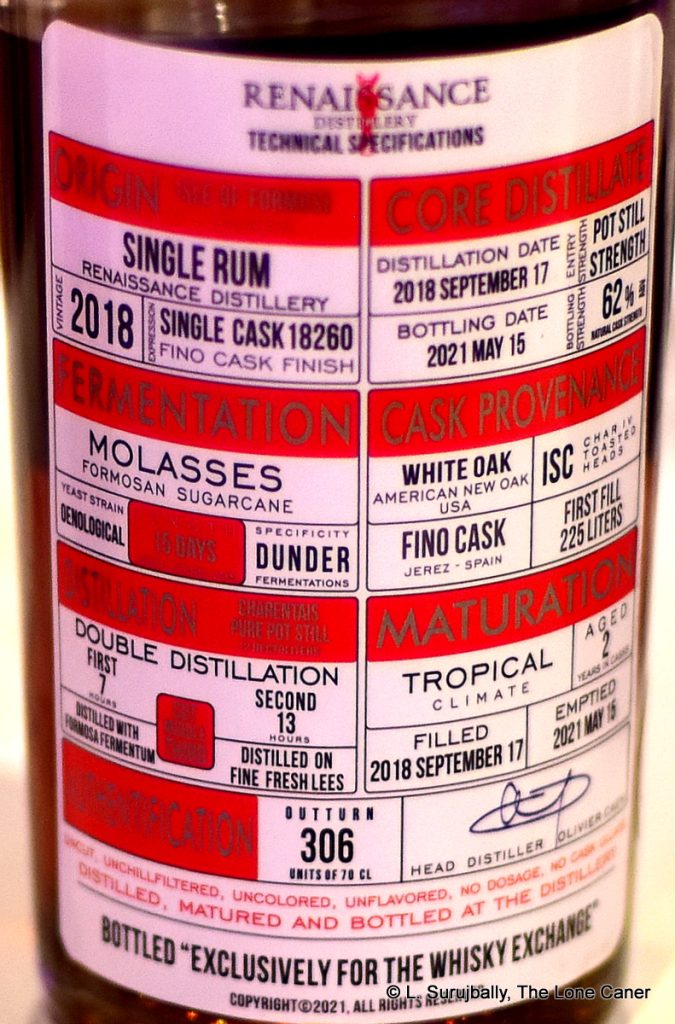

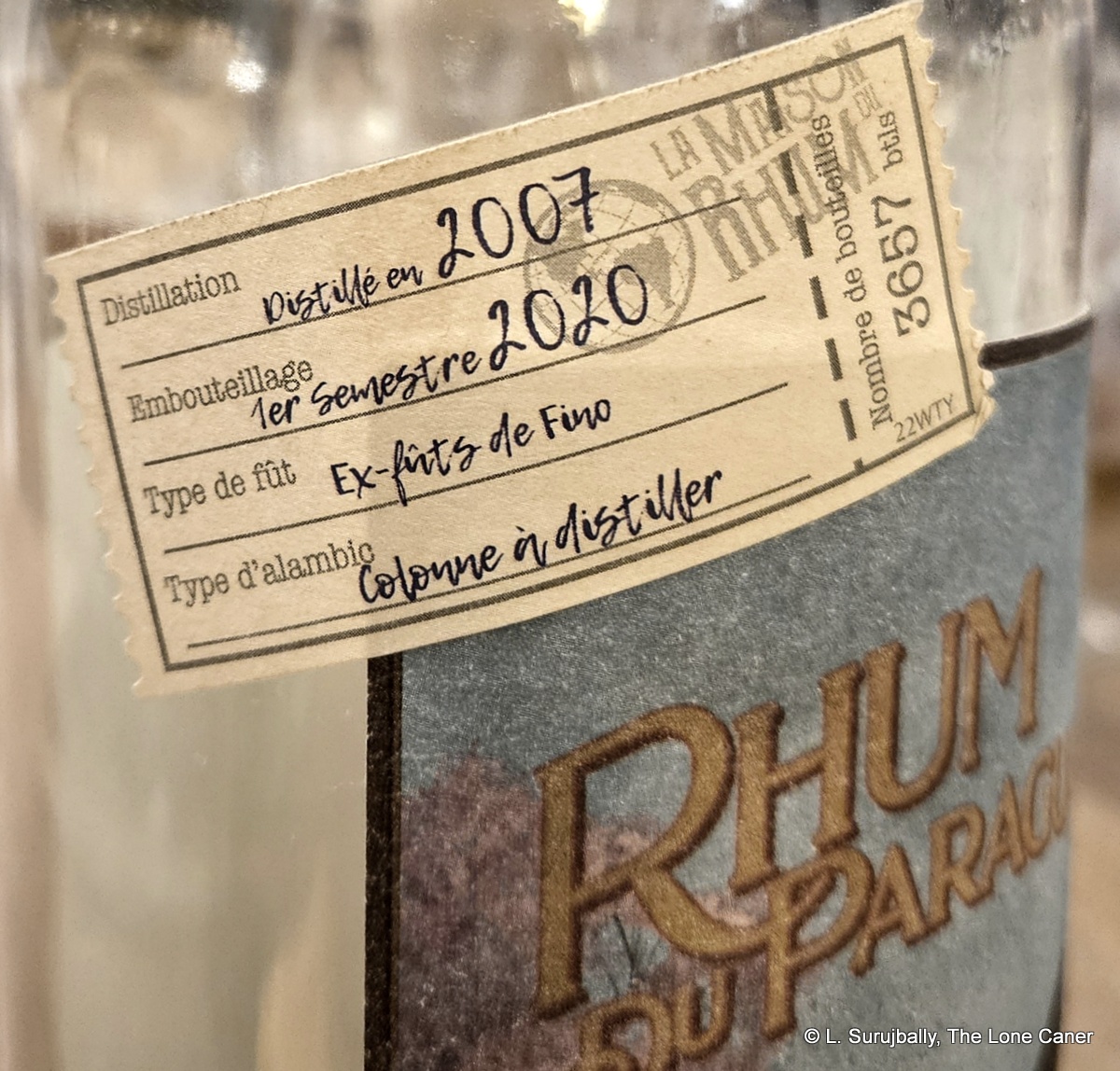

The production notes are as follows, and have not appreciably changed since the original Heroica review. The rum is made from rendered sugar cane juice (“honey”), fermented for 72 hours using wild yeast, column distilled, then aged in a American ex-bourbon barrels, then given a few months’ additional finishing in Fino sherry casks, so it seems reasonable to suppose it’s double aged: in Paraguay and then in Europe. Given the outturn of nearly 4,000 bottles, I believe that LMdR got the final blended product and that part had some European ageing, including the finish, for a total of 13 years (but this is not for sure, since Fortin also does finishing). Released at a middling 45% ABV. Oh, and it should be noted that this is Batch #3 – as of early 2026 I think they are up to #6, all bottled in the forties ABV range.

This is where an indie bottling (which this is) gets more respect for disclosure that Fortin did – by a whisker. That is, unfortunately, not enough to elevate it over and above its sibling, even with the more serious age and the finish. Consider the nose. This is dusty and rather dry (the sherry influence helps here). Initial dry notes of cardboard, straw and damp tobacco, mix it up with vanilla, cinnamon, honey. A trace of glue and salted caramel, and if one strains, perhaps a touch of citrus and mango.

This is where an indie bottling (which this is) gets more respect for disclosure that Fortin did – by a whisker. That is, unfortunately, not enough to elevate it over and above its sibling, even with the more serious age and the finish. Consider the nose. This is dusty and rather dry (the sherry influence helps here). Initial dry notes of cardboard, straw and damp tobacco, mix it up with vanilla, cinnamon, honey. A trace of glue and salted caramel, and if one strains, perhaps a touch of citrus and mango.

Taste? Meh. Not much more here – the dryness persists, there’s some grapes, and glue, the mangoes (or is that pineapple?) hints are back, and beyond that it’s all the standard hits of a barrel aged rum – caramel, toffee, some coffee grounds, wet ashes, honey, cinnamon, vanilla and mild cigar smoke, all tied up with an unenthusiastic and quick finish that is as straightforward as all the preceding tastes, and adds nothing new to the party.

Honestly, even at 45%, it’s nothing special, and as I have noted before, any rum based on sugar cane juice – actual or rendered down – loses its connection to the terroire with prolonged barrel ageing, which is exactly what happens here. So one is left to wonder what the selling point of a rum so ordinary really is. The unusual country of origin? The bottler?

The original Heroica was bottled at 40% and that more or less failed – perhaps I was generous with that 79 point score back in 2020. Here, even at five proof points higher, it still doesn’t do much and scores a point less. For those who enjoy the easier, lighter Latin style of rum making, sure, why not? For those who like their uncompromising cask strength growlers, I’d suggest that even with La Maison’s imprimatur on the label, the ultimate result is a rum that is slickly made, nicely labelled, but buggy in execution, reminding me of nothing more than a premature software update which does nothing in particular and relies on the brand to sell.

(#1137)(78/100) ⭐⭐⭐

Other notes

Background

Paraguay — one of two landlocked countries in South America is something of a newcomer on the international rum scene, and most of the rums they have made that are distributed abroad have only come on the scene in the last two decades — previously, just about the entire production was local, or regional. So far they have stuck with the traditional rons and not gone too far off the reservation. All that is now changing, as they begin to seek a space on the export shelf.

Fortin, the overall brand of the distillery called Castilla, dates from the post-1989 era and takes advantage of a change in legislation regarding alcohol at that time. From 1941 to 1989 the production and sale of alcohol (and spirits) was a state monopoly, run by the Paraguayan Alcohol Corporation in which the Government and producers both had stakes. Officially this was to rationalize standards, assign quotas, regulate competition and prevent tax evasion, but in reality it was to ensure the commercial elites went into business with the government to share in / siphon off the revenues. After Alfredo Stroessner (the last of a series of military jefes ruling since the 1930s) was toppled in 1989 the laws were relaxed and private industry began to revive.

Castilla Distillery was formed around 1993 as a sugar producer by Gustavo Díaz de Vivar, and although it started in Capiatá area to the immediate SE of the capital, Asunción, the company soon moved further east to the town of Piribebuy; after the sugar business took off, he and his son Javier Díaz de Vivar (the current president of the company) diversified into rum production with a multi-column still bolted onto the already existing sugar factory they had built..

The distillery is located on a small estate of about 1,500 hectares (~3700 acres) where the sugarcane is grown. The cane is cultivated according to organic farming principles and is apparently manually harvested. They age in all kinds of barrels – American oak (ex-bourbon), cognac, sherry, and also Marcuya “fruit of passion” wood from Paraguay. Once that’s done, the resultant rons are blended to form the final product and released under the Fortin label, or, perhaps, sold on to brokers and intermediaries in Europe for the independent bottling scene.