In any festival featuring rums, there are always a few that are special (if only to oneself), and the larger the festival the more they are…and usually, the harder they are to find. Sometimes they only exist below the counter, provided by people who know (and hopefully like) you enough to spot a shot. Occasionally, you are alerted to potential finds by fellow enthusiasts who scurry around ferreting out the new, the amazing, the obscure, or the just plain batsh*t crazy, and then they tell you — maybe. Alas, in many cases there are only limited stocks and others are sure to be there before you — so if you dally and tarry, you’re out of luck. And so you hustle to get your dram…if any is left.

At an event as large as Paris’s 2024 WhiskyLive, which I attended a few days ago for the second time, the problem becomes acute because at the VIP area where almost all such nuggets are to be found, all the top end spirits and new releases are jammed together and the booths are five and six deep in people wanting to do exactly what you are. In this way I missed out on a 1950s Cuban rum (sniffed but not tasted), a LMW full proof rum from Cambodia (never even spotted), and several fascinating rums from the Caribbean (the list is long). There just wasn’t enough time or enough energy to elbow one’s way past and through the crowds.

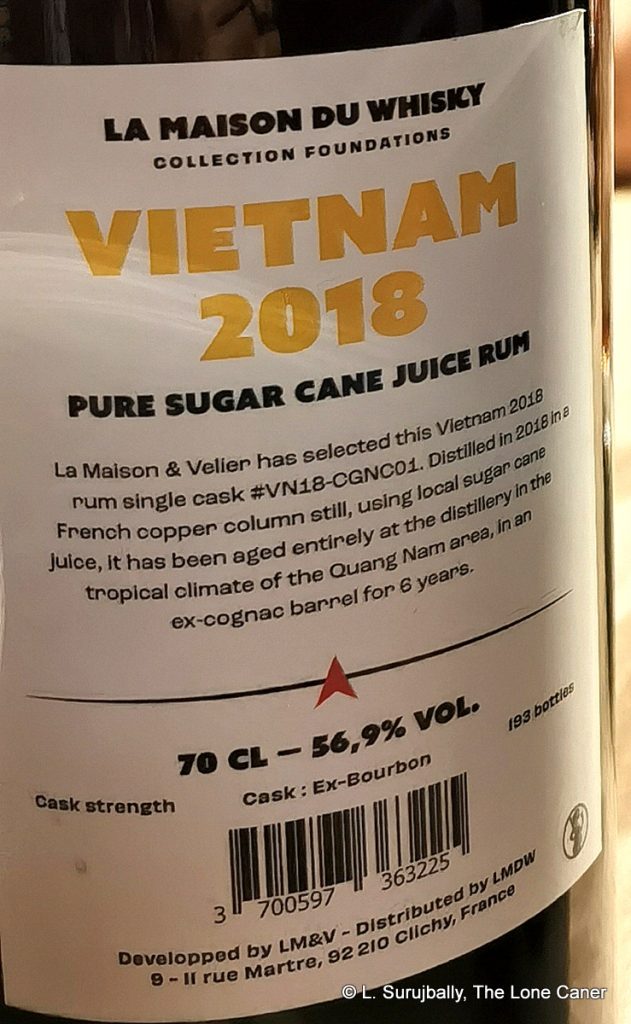

But on the flip side, I managed to try this surprising rumlet, on the very last day, in my final hours: a cane juice rum from Viet Nam’s Quang Nam province, distilled on a French copper column still and then aged in ex-bourbon and ex-Cognac casks (we are not told how much of each), before being bottled six years further on, at 56.9%. That’s pretty much all we get. It has been placed in the annual La Maison collection called Foundations, and is itself a part of the LM&V series called “Flags”, which are all distinguished by labels bearing a stylized – almost abstract – flag of the country of origin.

Because we see so little rum from Asia that isn’t messed with in some way or issued at some yawn-through low strength, you can understand my eagerness to try it. I can assure yo, this six year old does not disappoint. It noses in a faintly vegetal way, redolent of grass and cane sap. It is quite pungent and aromatic to a fault, channelling a crisp semi-sweet white wine, ripe green grapes, a touch of brininess, combined with vague notes of lychees and green apples. There are even scents of hot pastries, lemon meringue pie, plus a dash of white chocolate and – I swear this is true – raw potato peelings.

This all comes together in a palate of uncommon restraint, at that strength. It’s salty and very crisp, with a grain background that makes it almost whisky-like, yet there are sweetish notes too, as well as caramel, toffee, white chocolate and almonds and a creamy unsweetened greek yoghurt. There are some watery white fruit in evidence – pears, melons, white guavas, that kind of thing – and the general taste is of something quite light and perfumed, leading to a civilised and easygoing finish, quite aromatic and fruity and floral, yet with some breakfast spices as well. It’s really pleasant rum to drink and not one I’d care to mix, really.

This all comes together in a palate of uncommon restraint, at that strength. It’s salty and very crisp, with a grain background that makes it almost whisky-like, yet there are sweetish notes too, as well as caramel, toffee, white chocolate and almonds and a creamy unsweetened greek yoghurt. There are some watery white fruit in evidence – pears, melons, white guavas, that kind of thing – and the general taste is of something quite light and perfumed, leading to a civilised and easygoing finish, quite aromatic and fruity and floral, yet with some breakfast spices as well. It’s really pleasant rum to drink and not one I’d care to mix, really.

The rum noses really well and tastes even better, and still manages to carve out its own little niche with some subtle hints of terroire that distinguish it from the rhums adhering to more exacting AOC standards, with which we are also more familiar. That’s its attraction, I think, that air of something at a slight remove from the well known. Yet the final impression one is left with is that the agricole nature of it all has started to recede as the age increases and the barrels take on more of an influence, and dilute the distinct notes of its origin.

That’s an observation, not a criticism, because overall, the rum is great – and my score reflects that. I just want you to be aware that even at a mere six years of age, we are losing a little of that clear sense of origin – something that says “Vietnam”. And to get that, we may have to turn to the source, and check out a white or two from there. Until we can do that, we must be grateful for this one: because this rum is no slouch, is a good addition to anyone’s collection, and deserves too be sampled. And keeping in mind my desire for the new and obscure, am I ever glad I tried it.

(#1092)(86/100) ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Other notes

- Video Recap is here

- Outturn is 193 bottles. The LMV catalogue says 440+ but since the catalogue goes to print before the final bottling, I take the label as my guide here.

- The question of course is which distillery made it, and my own educated guess is based on the following factors: the province of Quang Nam, the French copper pot still, and the fact that no fly-by-night small-batch operator would interest Velier or La Maison – at the very least there would have to be some street cred involved, and that eliminates Belami (too small), Mia (wrong location, different still), or L’Arrange (too involved in fruit infusions). Which leaves just one which ticks all the boxes – Sampan, of which I’ve tried just one, and was mightily taken by. If I’m right about that, a brief company bio is in the review of their white overproof rum.

- Thanks to Kegan, who sent me to the right place just in time to get a final dram from the chaotic counter.

Consider first the nose of this

Consider first the nose of this