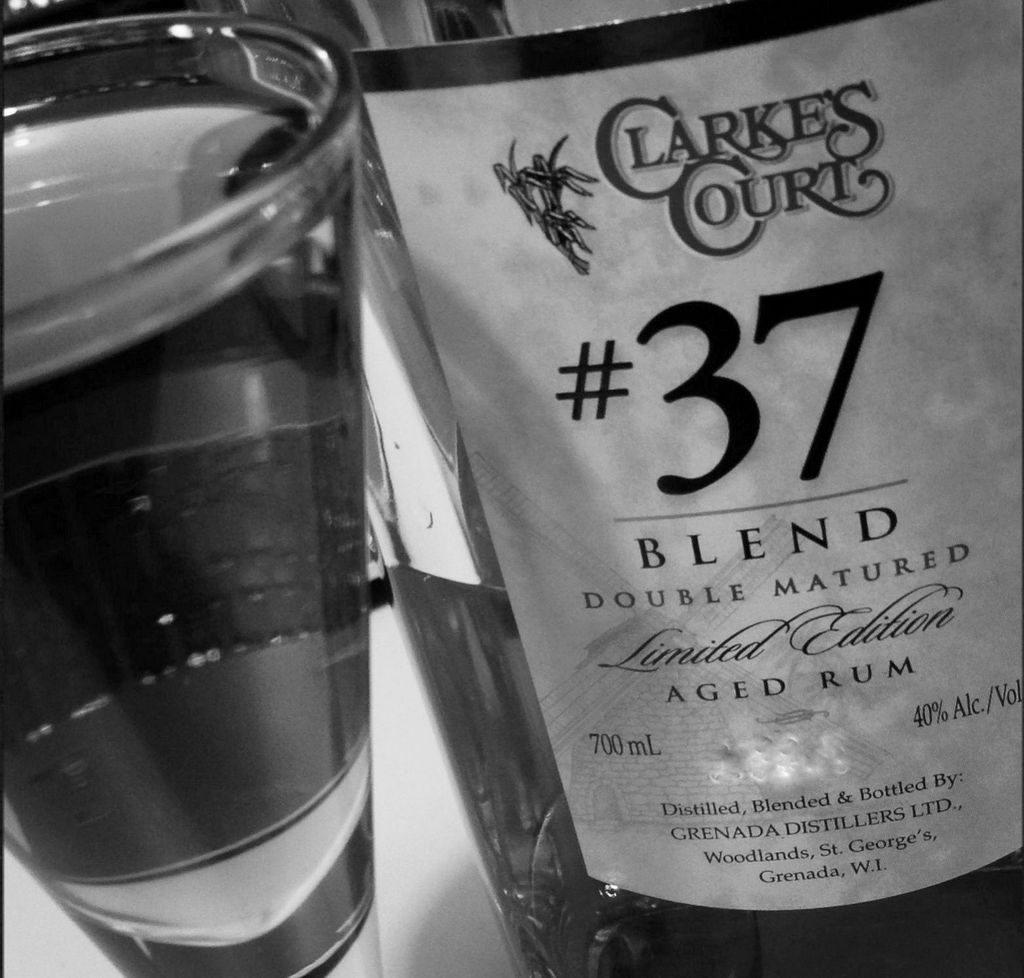

There are four operations making rum in Grenada – Renegade (the new kid on the block, operating since 2021), Westerhall, Rivers Antoine and Clarke’s Court, the last of which was formed in 1937, operating under the umbrella of the Grenada Sugar Factory (the largest on the island) and named after an estate of the same name in the southern parish of St. George’s. This title in turn derived from two separate sources: Gedney Clarke, who bought the Woodlands estate from the French in the late 1700s, and a bay called “Court Bay” included with the property (this in turn was originally titled “Watering Bay” because of the fresh water springs, but how it came to change to Court is not recorded). The company sold rums with names like Tradewinds and Red Neck before the Clarke’s Court moniker became the standard, though the exact date this happened is uncertain. Pre-1980s, I would hazard.

The Clarke’s Court Pure White Overproof is a column-still, molasses-based blended white lightning made by that company, and is apparently the most popular rum on the Spice Island, best had with some Angostura bitters (the 43% darker rums made here are supposedly for the ladies, who “prefer gentler rums”). Local wags claim it’ll add hair to your chest, strip the paint off anything, and can run your car if you don’t have any petrol. Older women reputedly still use it as a rub.

When it comes to seriously pumped-up Grenadian rums, Westerhall’s Jack Iron is not in this rum’s league, though it’s admittedly stronger; and had Clarke’s more distinct, it would have given Rivers Antoine a run for its money as the first Key Rum from Grenada. It certainly buffs its chest and tries to muscle in on the territory of the famed white Jamaicans (I feel it was meant to take on J. Wray’s White Overproof, or even DDL’s amusing three-lies-in-one Superior High Wine…but it lacks their fierce pleasures and distinct profiles and at the end, is something of a cheap high proofed white rum shot with ‘tude and taste, a better Bacardi Superior with a dash of steroids.

This careful endorsement of mine does not, however, stop it from being something of a best-selling island favourite on Grenada, where it outsells Rivers (because of a larger facility that breaks down less frequently). As with other white rums across the Caribbean, it’s an affordable and powerful rum, a dram available to and drunk across all social classes — it’s always been made and probably always will be. It’s emblematic of the island and widely known in a way Rivers – which is far older – is only now becoming, and local denizens with a creative juice-it-up bent cheerfully adulterate, spice up or make “bush” variations (such as the one I originally tried back in 2010) at the drop of a hat and in every rum shop up and down the island.

This careful endorsement of mine does not, however, stop it from being something of a best-selling island favourite on Grenada, where it outsells Rivers (because of a larger facility that breaks down less frequently). As with other white rums across the Caribbean, it’s an affordable and powerful rum, a dram available to and drunk across all social classes — it’s always been made and probably always will be. It’s emblematic of the island and widely known in a way Rivers – which is far older – is only now becoming, and local denizens with a creative juice-it-up bent cheerfully adulterate, spice up or make “bush” variations (such as the one I originally tried back in 2010) at the drop of a hat and in every rum shop up and down the island.

Now, it’s torqued up to 69% ABV, but sources are unclear whether it has been aged a bit then filtered, or is released as is, and while I can’t state it with authority, I believe it to be unaged: it has a series of aromas and tastes that just bend my mind that way. The nose, for example, is redolent of minerals, dust, watery salt solution, the smell of the ocean on a seaport where the fish and salt water reek is omnipresent. Some sweet swank and sugar cane juice – there’s a weird and pleasant young-agricole vibe to the experience – plus a delicate line of fruits: sharp, ester-y, unripe, tart and pungent, without the rich plumpness of better-made aged variants. Kiwi fruit, and one of those cheap mix-everything-in fruit juice melanges. Honestly, I got a lot here, and had walked in expecting a lot less.

69% is strong for a rum, but not unbearable, and it’s just a matter of sipping carefully and expecting some heat for your trouble. Tastes of apples, cider, pears, all sour, begin the experience. These initial flavours are then muscled aside by tequila and brine and olives, not entirely pleasant, very solid; this then morphs into a sweet and sour soup, yeasty bread, cereals, sour cream, cream cheese, all very strong and firm, reasonably well developed and decently balanced. The fruits are also well represented – one can sense a fruit salad with cherries in syrup, plus gherkins and the metallic hint of a copper penny. Overall, surprisingly creamy on the tongue, almost smooth: not what one would expect from something at this proof point. It leads nicely into a hot, long finish, with closing notes of fruits (bananas, watermelon, mangoes) and some salt-sour mango achar, miso soup, and sweet soya.

69% is strong for a rum, but not unbearable, and it’s just a matter of sipping carefully and expecting some heat for your trouble. Tastes of apples, cider, pears, all sour, begin the experience. These initial flavours are then muscled aside by tequila and brine and olives, not entirely pleasant, very solid; this then morphs into a sweet and sour soup, yeasty bread, cereals, sour cream, cream cheese, all very strong and firm, reasonably well developed and decently balanced. The fruits are also well represented – one can sense a fruit salad with cherries in syrup, plus gherkins and the metallic hint of a copper penny. Overall, surprisingly creamy on the tongue, almost smooth: not what one would expect from something at this proof point. It leads nicely into a hot, long finish, with closing notes of fruits (bananas, watermelon, mangoes) and some salt-sour mango achar, miso soup, and sweet soya.

When considered against the other big-name, well known, badass whites from the non-agricole, non-151-proof world, it’s easy to see why it gets less respect than the howitzers from Jamaica, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and Guyana (for my money, Cuba, T&T and Barbados have no overproof white rums that stand out, are as well known, or are so visibly a part of local culture in the way these are, though I’m sure I’ll catch some heated protests about that). It’s not exported in quantity, lacks a solid presence on the American bar and cocktail circuit, doesn’t often come in for mention and has no superstar brand ambassador or cocktail-slinging badass to champion its praises – many people reading this review will likely never have tried it.

That said, I think it may be an undiscovered steal. Grenadians, to whom it’s a cultural institution, will swear by the thing and embrace anyone who speaks positively of the rum like a brother. Few will drink it neat: I do it so you don’t have to, but really, it’s not made to have that way, and that leaves it to boost a mix of some kind, like the locals who have it with a soda, juice or coconut water (when they don’t throw back shots in a rumshop, or nip at the backpocket flattie all day). The tastes are nothing to sneeze at, there’s enough raw flavour and bombast and attitude here to satisfy the desire for something serious for the rum junkie, and the bottom line is, it’s really and surprisingly good. It’s a worthy entry to the canon, and one can only hope it gets wider international acclaim. We can always use another one of these.

(#871)(83/100)

Other Notes

- This review is based on two separate sample tastings – a mini from the 1990s and a more recent sample bottle bought from Drinks by the Dram. The tastes were similar enough to suggest the blend has stayed the same for a long period.

- The label has remained relatively unchanged for decades. It is unknown when the rum was first introduced though.