A fascinating introduction into the twists and turns an agricole rhum profile can take

To the extent that agricoles have their own flavour profile, they haven’t surprised me much yet. My tastes were formed by products from Clemente, Rum Nation, Damoiseau, Depaz, J. Bally, Trois Rivieres and others, and there were always those herbal and grassy notes to them and displayed similar general characteristics. That was until I ran through four Neissons one after the other…and was forced to conclude that agricoles can be just as fascinating and unusual as any other sugar cane drink. Seriously – Neisson may make some of the most distinctive agricole rhums I’ve ever tried. They’re demonstrably cane juice rums, sure…but then they happily head off into undiscovered country.

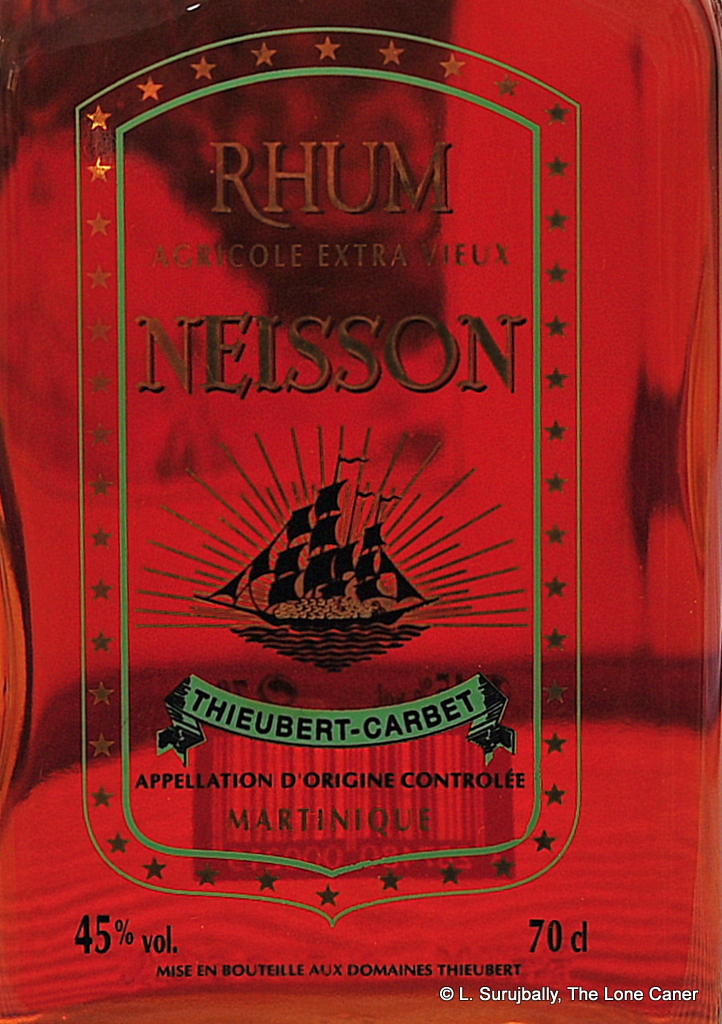

The Extra Vieux, which in the absence of better information I’m tentatively saying is 6-10 years old was bottled at 45% and was an amber-brown, which I tried with its siblings from the same company, and then added a Rhum Rhum Liberation and a CDI Guadeloupe 16 YO…just to be sure.

Follow me through the tasting and let me describe what I tried. The divergence from the norm began with the scents it gave off when poured. Neither overly sweetly scented or too deep in profile, it was had solid fruity credentials, and had some of the muskiness I usually associated with tequila, combining that with the meatiness of salt beef. So already, some interesting digressions. The rhum’s aromas went away surprisingly swiftly, so re-sniffing was in order, and it was a little less tamed, a little more raw than one would expect. Once it opened up some more, it also manifested a certain lack of snap and crispness I sometimes associate with younger agricoles, yet one could not entirely fault the result, which was thick and creamy, very well rounded (perhaps I never quite understood the term before now), mixing in coconut shavings, butter and a nice Philadelphia. Another odd thing was the absence of clearly identifiable grassy notes – others might disagree, but I hardly smelled any vegetals or herbaceous elements at all.

The palate continued in this provocative vein: it was warm, displaying characteristics of fleshy fruit rather than the cleanliness of freshly mown lemon-grass (though some of that crept through, now). In a way it was quite winey, with tastes of sauternes, vanilla and sour cream mixed in with a fruit salad that had a few too many red grapes and currants. Yet the smoothness and heft to the mouthfeel, the overall texture, were quite good, once I got past a set of divergent tastes and just went along for the ride without projecting my own expectations or preconceived notions on the thing. The fade was perhaps the most traditional thing about this rhum, being short and lush (not dry at all); sweetish, closing with scents of nuts, red grapes, butter (again)…and, weirdly enough, caramel (what was that doing here?).

Neisson has existed in Martinique since 1922 when the Neisson family started the plantation (the distillery was started in 1931). Nowadays it is run by the son and daughter of the founder, and they hold almost 9000 acres of cane under cultivation close by Le Carbet in northwestern Martinique (Depaz is up the road, and Dillon a little further south east of it). Cane is not burnt as it is in Guyana prior to harvesting, and the cane is crushed in a steam engine driven crusher. Fermentation takes about three days before being distilled in a single column copper Savalle still: the 65-70% distillate is stored for about three months in a stainless steel vat while being regularly stirred to eliminate unwanted volatile elements, before being transferred to 180-200 liter French or American oak barrels for ageing — most for a minimum of four years, but some for only 18 months, the latter to produce what is known as “Elevé sous bois”, or stored in wood, rum.

So all that aside, does the rum work? Well, yes and no. It’s nowhere near as fierce and individualistic as, say, the Clairins, and that does take some getting used to. The integration of the taste components is done well, it’s not very sweet, and the mouthfeel isn’t bad at all. Where it falls down a little, for me, is in that salty tequila-like undertone, and where it succeeds is in the gradual unfolding of character and complexity.

I wasn’t totally enthralled, at first…yet kept getting pulled back to it, largely due to its queer and unique originality, which was like an almost-but-not-quite familiar face one sees in a party. The Neisson Extra Vieux does a right turn and then a twist on the standard conceptions of what an agricole should be, building up to an idiosyncrasy that requires both some adjustment, and some patience. If you have those and are willing to meet it on its own terms, this AOC rhum is actually quite an experience.

(#255. 84/100)

Great review, I didn’t know much about Neisson, but now intrigued to try one.

You mentioned at the beginning the Compagnie des Indes Guadeloupe 16 – notice that it is, to my knowledge, an ‘industrial’ (made from molasses) rather than agricole. So I guess it stood out quite a bit in the tasting?

I think going up the ladder to something older might be better…I have three other reviews of older Neissons to write and they scored a little higher than this one.

I’m unsure if the Guadeloupe was industrial or a true agricole. Of course, they don’t have an AOC certification over there, so variation is allowed. Once I do the research, I’ll know for sure. And yes, it stood out a bit.

I only wish other people would review products in as much detail as you do. Bravo!