Photo crop courtesy of the Ultimate Rum Guide, as mine turned out to be crap.

A little too thin and out of balance for my palate, though the tastes are intriguing.

A few words about Mauritius, an island nation in the Indian Ocean to the east of Madagascar, which has been at varying times composed of more islands and fewer, and either Dutch, English or French…though Arabs and Portuguese both made landfall there before initial failed colonization (by the Dutch) in 1638. However, its strategic position in the Indian Ocean made both French and British fight for it during the Age of Empires, and both remain represented on the island to this day, melding with the Indian and Asian cultures that also form a sizeable bulk of the population. The volcanic nature of the soil and tropical climate made it well suited for sugar cane, and there were thirty seven distilleries operational by 1878, who sold mainly to Africa and Madagascar.

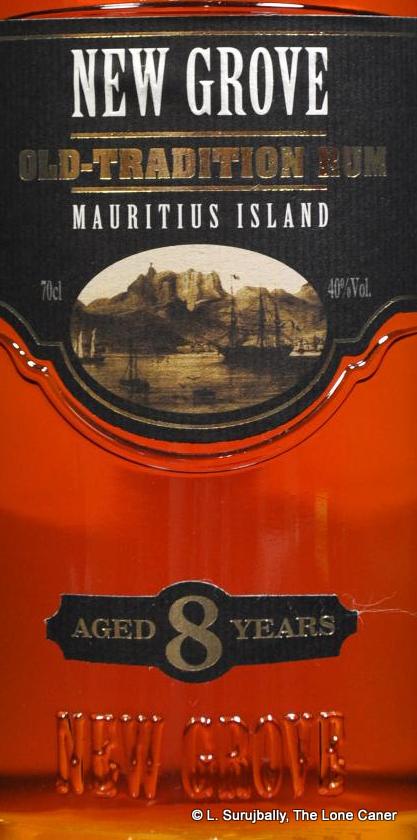

New Grove is a rum made on that island, and while the official marketing blurbs on the Grays website tout a Dr. Harel creating the rum industry back in 1852, the first sugar mill dates back to 1740 in Domain de la Veillebague, in the village of Pampelmousses, with the first distillery starting up two years later: New Grove is still made in that area, supposedly still using the original formula. The Harel family have moved into other concerns (like the Harel-Mallac group, not at all into agriculture), but other descendants formed and work for Grays – one of them sent me the company bio, for example, and three more sit on the board of directors.

Grays itself was formed in 1935 (the holding company Terra Brands, was established in 1931 by the Harels and the first still brought into operation in 1932) and are a vertically integrated spirits producer and importer. They own all stages of local production, from cane to cork, so to speak, and make cane spirit, white rum, a solera and aged rums, for the Old Mill and New Grove brands which were established in 2003 for the export market.

It was the eight year old New Grove which I was looking at this time around. The molasses is fermented for 36 hours and then distilled in a column still; the emergent 65-80% spirit is then packed away in oak for preliminary ageing (about eight months) and then transferred into Limousin oak – about 30% of these barrels are new – for the final slumber.

So all these are technical details, you say, historical stuff…what’s the rum like?

Well, not too shabby, actually. Even at 40%, the copper-gold 8 year old was intriguing. I mean…ripe mangoes right off the bat? Although the initial nose presented itself rather sharply – probably because I pushed my beak into the glass too quickly and hadn’t waited a little – it did mellow out a little. Sharpish yellow fruits – peaches, unripe papaya, lemon peel, green grapes – predominated, and had a tang to it (that mango thing) which was quite unusual. The downside was that the balance of the vanillas an tannins and caramel – the muskier molasses side of things, if you will – was edged out, and some of the overall coherence was therefore lost.

On the palate, the flavours continued their emergence without much more, but the whole mouthfeel was disconcertingly thin, and even a bit spiteful. This gradually retreated and the taste after a bit gave way to a much softer profile of red guavas, firm yellow Indian mangoes (they’re slightly different in taste to Caribbean ones I grew up with), ginger, papaya again…and a taste of white soursop as well. So taste wise, I liked it – sort of – but the overall balance problem did persist, and the lack of heft and body kinda sank the experience for me. Things were rescued somewhat by a relatively long fade, smooth and warm, nothing to be afraid of. A whiff of tobacco, some brown sugar and vanilla at last, a tad of smokiness – it was odd how the fruity nature disappeared, leaving more traditional elements to finally take their moment on the stage only at the final bow.

So overall, not anything to I was going to get hugely enthusiastic about. I should mention that this eight year old has in fact won silver and gold awards in 2013 and 2014 on the European festival circuit (Madrid, German ISW, Belgium, and UK IWCS) so certainly others take a less unforgiving approach to the spirit than I do. But what can I say – it’s a rum, it’s aged, it’s decently made, but it doesn’t really come together, sock me in the jaw and shiver me timbers. I’d much rather take a look at New Grove’s 2013 limited single barrel expressions from the 2004 output, aged longer and with a higher proof point…I have a feeling I might appreciate these more. That said, note that for a US$50 price point, the eight year old will likely be enjoyed by many and is reasonably affordable. Only time will tell how sales and the expression’s reputation develop.

(#216. 81/100)