Ahh, that magical number of 23, so beloved of rum drinking lovers of sweet, so despised by those who only go for the “pure”. Is there any pair of digits more guaranteed to raise the blood pressure of those who want to make an example of Rum Gone Wrong? Surely, after the decades of crap Zacapa kept and keeps getting, no promoter or brand owner worth their salt would suggest using it on a label for their own product?

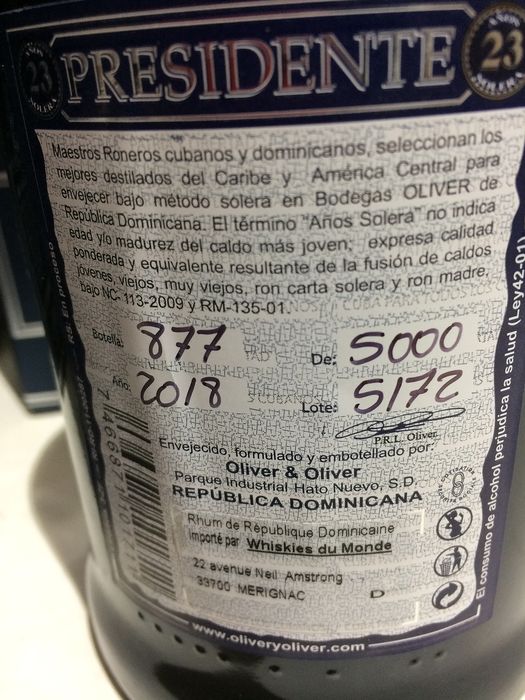

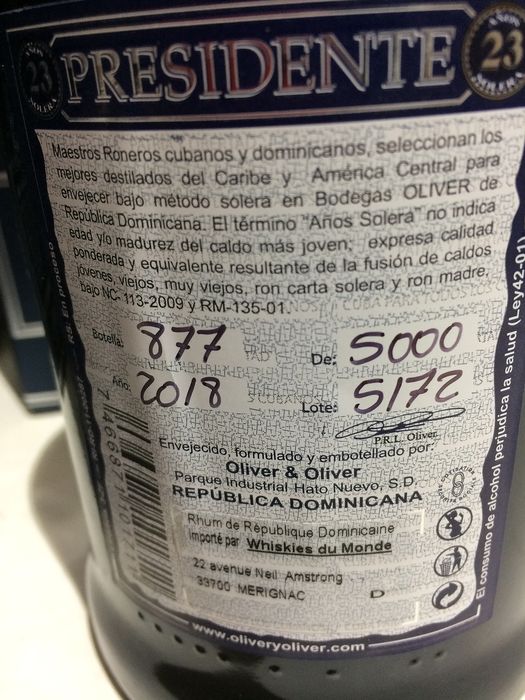

Alas, such is not the case. Although existing in the shadow of its much-more-famous Guatemalan cousin, Ron Presidente is supposedly made the same way, via a solera method of blending about which not enough is disclosed, so I don’t really buy into (too often what is claimed as a solera is just a complex blend). Oliver & Oliver, a blending company operating in the Dominican Republic, was revived in 1994 by the grandson of the original founder Oliver Juanillo who had fled Cuba in 1959. It is a company whose webpage you have to peruse with some care: it’s very slick and glossy, but it’s not until you really think about it that you realize they never actually mention a distillery, a specific type of still, source of distillate, or any kind of production technique (the words “traditional pot-still method” are useful only to illustrate the need for a word like cumberworld).

That’s probably because O&O isn’t an outfit formed around a distillery of its own (in spite of the header on Flaviar’s mini bio that implies they are), but is a second-party producer – they take rum from elsewhere and do additional work on it. Where is “elsewhere?” It is never mentioned though it’s most likely one of the three B’s (Bermudez, Barcelo, Brugal) who have more well known and legitimate operations on the island, plus perhaps further afield as the back label implies..

Well fine, they can do that and you can read my opinion on the matter below, but for the moment, does it stand up to other rums, or even compare to the well-loved and much-derided Zacapa?

I’d suggest not. It is, in a word, simple. It has an opening nose of caramel, toffee and nougat, hinting at molasses origins and oak ageing. Some raisins and prunes and easy fruit that aren’t tart or overly sweet. Plus some molasses, ripe papaya, and strewed apples and maple syrup. And that syrup really gets big in a hurry, blotting out everything in its path, so you get fruits, sweet, and little depth of any kind, just a sulky kind of heaviness that I recall from El Dorado’s 25 Year Old Rums…and all this from a 40% rum.

It gets no better when tasted. It’s very darkly sweet, liqueur-like, giving up flavours of prunes and stewed apples (again); dates; peaches in syrup, yes, more syrup, vanilla and a touch of cocoa. Honey, Cointreau, and both cloying and wispy at the same time, with a last gasp of caramel and toffee. The finish is thankfully short, sweet, thin, faint, nothing new except maybe some creme brulee. It’s a rum that, in spite of its big number and heroic Jose Marti visage screams neither quality or complexity. Mostly it yawns “boring!”

It gets no better when tasted. It’s very darkly sweet, liqueur-like, giving up flavours of prunes and stewed apples (again); dates; peaches in syrup, yes, more syrup, vanilla and a touch of cocoa. Honey, Cointreau, and both cloying and wispy at the same time, with a last gasp of caramel and toffee. The finish is thankfully short, sweet, thin, faint, nothing new except maybe some creme brulee. It’s a rum that, in spite of its big number and heroic Jose Marti visage screams neither quality or complexity. Mostly it yawns “boring!”

Overall, the sense of being tamped down, of being smothered, is evident here, and I know that both Master Quill (in 2016) and Serge Valentin (in 2014) felt it had been sweetened (I agree). Oliver & Oliver makes much of the 200+ awards its rums have gotten over the years, but the real takeaway from the list is how few there are from more recent times when more exacting, if unofficial, standards were adopted by the judges who adjudicate such matters.

It’s hard to be neutral about rums like this. Years ago, Dave Russell advised me not to be such a hardass on rums which I might perhaps not care for, but which are popular and well loved and enjoyed by those for whom it is meant, especially those in its country of origin — for the most part, I do try to adhere to his advice. But at some point I have to simply dig in my heels and say to consumers that this is what I think, what I feel, this is my opinion on the rums you might like. And whatever others with differing tastes from mine might think or enjoy (and all power to them – it’s their money, their palate, their choice), this rum really isn’t for me.

(#794)(74/100)

Other Notes

- The rum is named “Presidente”. Which Presidente is hard to say since the picture on the label is of Jose Marti, a leading 19th century Cuban man of letters and a national hero of that country. Maybe it’s a word to denote excellence or something, the top of the heap. Ummm….okay.

- On the back label it says it comes from a blend of Caribbean and Central American rums (but not which or in what proportions or what ages these were). Not very helpful.

- Alex Van der Veer, thanks for the sample….

Opinion

I’ve remarked on the business of trust for rum-making companies before, and that a lot of the compact between consumer and creator comes from the honest, reasonably complete provision of information…not its lack.

I make no moral judgements on Oliver & Oliver’s production strategy, and I don’t deny them the right to indulge in the commercial practice of outsourcing the distillate — I simply do not understand why it’s so difficult to disclose more about the sources, and what O&O do with the rums afterwards. What harm is there in this? In fact, I think it does such non-primary brand-makers a solid positive, because it shows they are doing their best to be open about what they are making, and how…and this raises trust. As I have written before (in the reviews of the Malecon 1979, Mombacho 1989, Don Papa Rare Cask and Dictador Best of 1977) when relevant info is left out as a deliberate marketing practice and conscious management choice, it casts doubt on everything else the company makes, to the point where nothing is believed.

Here we get no info on the source distillate (which is suggested to be cane juice, in some references, but of course is nowhere confirmed). Nothing on the companies providing the distillate. Nothing on the stills that made it (the “pot stills” business can be disregarded). We don’t even get the faux age-statement fig-leag “6-23” of Zacapa. We do get the word solera though, but by now, who would even believe that, or give a rodent’s derriere? The less that is given, the more people’s feeling of being duped comes into play and I really want to know who in O&O believes that such obfuscations and consequences redound to their brand’s benefit. Whoever it is should wake up and realize that that might have been okay ten years ago, but it sure isn’t now, and do us all a solid by resigning immediately thereafter.

It gets no better when tasted. It’s very darkly sweet, liqueur-like, giving up flavours of prunes and stewed apples (again); dates; peaches in syrup, yes, more syrup, vanilla and a touch of cocoa. Honey, Cointreau, and both cloying and wispy at the same time, with a last gasp of caramel and toffee. The finish is thankfully short, sweet, thin, faint, nothing new except maybe some creme brulee. It’s a rum that, in spite of its big number and heroic Jose Marti visage screams neither quality or complexity. Mostly it yawns “boring!”

It gets no better when tasted. It’s very darkly sweet, liqueur-like, giving up flavours of prunes and stewed apples (again); dates; peaches in syrup, yes, more syrup, vanilla and a touch of cocoa. Honey, Cointreau, and both cloying and wispy at the same time, with a last gasp of caramel and toffee. The finish is thankfully short, sweet, thin, faint, nothing new except maybe some creme brulee. It’s a rum that, in spite of its big number and heroic Jose Marti visage screams neither quality or complexity. Mostly it yawns “boring!”