The South African distillery of Mhoba is one of those small outfits like Richland, Privateer, A1710, Issan, Killik or J. Gow, that almost single handedly builds a reputation from scratch through dogged persistence and ever-increasing word of mouth, to the point where they exercise an influence on the whole conversation around rums. None of these are the only ones, or the first, to do what they do: but all of them have qualities that are more than just beginner’s luck, and elevate — even redefine — the category of rums for their entire country.

In the early 2010s, Mhoba’s founder, Robert Greaves, built several versions of his own small stills to continuously evolve and improve what he thought could be done with the rums he wanted to make; he played around with the technical aspects of crushing, fermenting and distilling, applied for a Liquor License in South Africa, and finally opened for serious business in 2015. Initial samples sent to the Miami Rum Festival in 2016 resulted in more tweaking, and by 2017 he was able to demo his wares at the UK and Mauritius rumfests; buoyed by positive feedback there, in late 2018 he had a series of rums he felt were definitely worth showing off which he presented in London that year and in Paris a few months later.

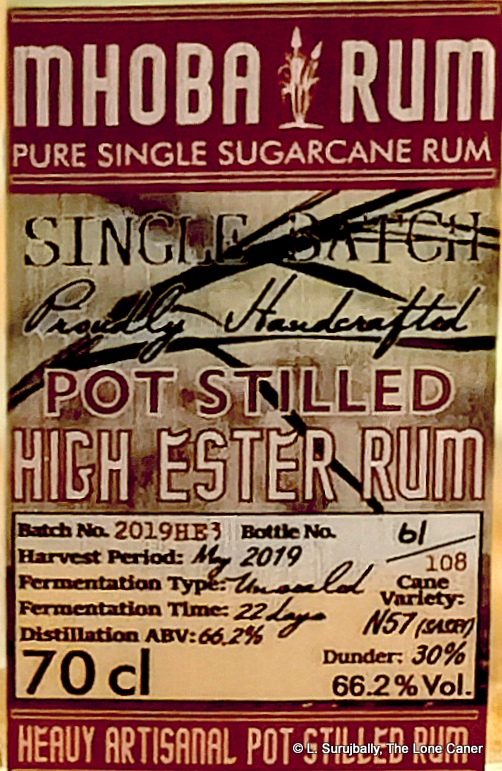

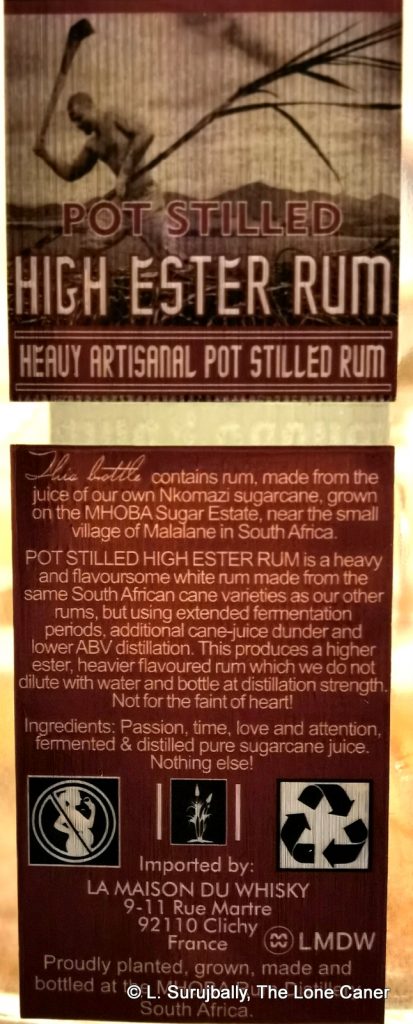

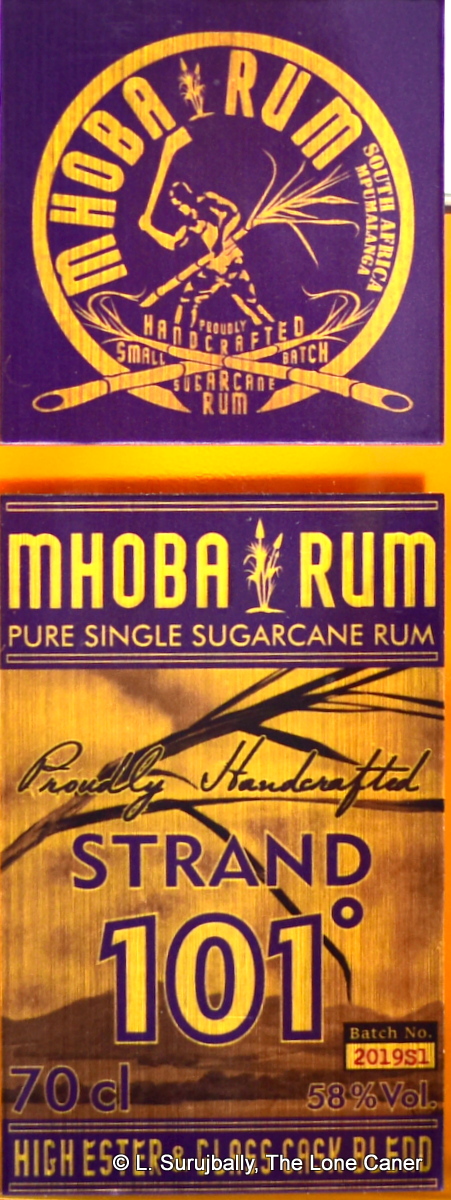

These initial rums were unaged white rums (from cane juice) at different strengths, various pot still blends and overproofs (like the Strand 101 and 151, Bushfire, French Oak, etc) and were soon on commercial sale. One of the most intriguing rums in the stable was the long-ferment unaged Pot Still High Ester white rum, which began being bottled in 2018 (two batches) before really hitting their stride in 2019. Each of these high ester rums is stuffed into a bottle with a label in dark red (maybe to alert the unwary) that has a ton of info on it – source cane variety, harvest date, fermentation, still type, batch number – yet oddly, the actual congener count is absent. This is not a deal breaker, of course, but it does strike me as odd since the “high-ester” description is its main selling point (because of course being a cane-juice pot-still-distillate at strength isn’t already enough).

These initial rums were unaged white rums (from cane juice) at different strengths, various pot still blends and overproofs (like the Strand 101 and 151, Bushfire, French Oak, etc) and were soon on commercial sale. One of the most intriguing rums in the stable was the long-ferment unaged Pot Still High Ester white rum, which began being bottled in 2018 (two batches) before really hitting their stride in 2019. Each of these high ester rums is stuffed into a bottle with a label in dark red (maybe to alert the unwary) that has a ton of info on it – source cane variety, harvest date, fermentation, still type, batch number – yet oddly, the actual congener count is absent. This is not a deal breaker, of course, but it does strike me as odd since the “high-ester” description is its main selling point (because of course being a cane-juice pot-still-distillate at strength isn’t already enough).

Anyway, these rums have all had the distinction of being made with about ⅓ dunder and with a three-week fermentation time using wild yeast, run through a pot still, and bottled consistently above 60% ABV (occasionally even over 70%). The one I’m writing about today is 66.2%, which is on the range’s weak side, I guess, but that in no way invalidated the intensity of what it presented.

Even nosed carefully, it was a powerful, sharp experience. It smelled like a whole shelf of fruits going off, poorly stored in a set of mouldy wooden crates stored under the waterlogged roof of an abandoned and dusty warehouse. Synthetic materials abounded: rubber, platicene, heavy plastic sheeting, new vinyl sofas, varnish, glue, nail polish remover, wax and a coat of cheap paint slapped onto fresh drywall. There’s a bagful of spanish olives cured in lemon juice and stuffed with pimentos, to which someone decided to add brine, olive oil and even more fruits – pineapples, strawberries, gooseberries, and hard yellow mangoes and the real issue is how much there is. I spent literally an hour going back to this one glass just to tease out more, but the codicil was that I enjoyed the nose less each time, as I got successively battered into near catatonia by ever-changing aromas that just never settled down.

Even nosed carefully, it was a powerful, sharp experience. It smelled like a whole shelf of fruits going off, poorly stored in a set of mouldy wooden crates stored under the waterlogged roof of an abandoned and dusty warehouse. Synthetic materials abounded: rubber, platicene, heavy plastic sheeting, new vinyl sofas, varnish, glue, nail polish remover, wax and a coat of cheap paint slapped onto fresh drywall. There’s a bagful of spanish olives cured in lemon juice and stuffed with pimentos, to which someone decided to add brine, olive oil and even more fruits – pineapples, strawberries, gooseberries, and hard yellow mangoes and the real issue is how much there is. I spent literally an hour going back to this one glass just to tease out more, but the codicil was that I enjoyed the nose less each time, as I got successively battered into near catatonia by ever-changing aromas that just never settled down.

This was more than compensated for in the way it tasted, however. The palate was much much better — better integrated, better controlled — while losing only some of the harsh pungency and untamed wildness the nose suggested I would find. It remained a stong and serious biff to the throat of course (it was a cheerfully violent street hood from start to finish, so that wasn’t going to change) but also nicely sweet and dry, with loads of pungent tastes: overripe Thai mangoes, pears, melons, peaches, kiwi fruits, bananas, orange peel, green tea and sugar cane juice. This took a breather here and there, and let in other tastes of acetones and turpentine…and if you could convert the smell of the inside of a nice new car to a taste, well, there was that too. There were notes of cream cheese, rye bread, strawberries, cinnamon, pineapples which also bled into the finish – which in turn was nicely long, very sharp and tartly sweet and chemical (in a good way) with a last hint of flowers and overripe fruits.

This is a rum that should not be casually drunk or bought on a whim. It’s surely not “easy.” It’s a hugely potent and feral mix of a Jamaican funk bomb and a Reunion Grand Arome, a clarin’s irreverent offspring with a visiting DOK, and if not approached with caution should at least be drunk with respect. After trying it, Mrs. Caner asked me incredulously, “Is this something you’re actually supposed to drink?” She has a point – I honestly believe that the Mhoba High-Ester rum could wake up a dead stick.

This is a rum that should not be casually drunk or bought on a whim. It’s surely not “easy.” It’s a hugely potent and feral mix of a Jamaican funk bomb and a Reunion Grand Arome, a clarin’s irreverent offspring with a visiting DOK, and if not approached with caution should at least be drunk with respect. After trying it, Mrs. Caner asked me incredulously, “Is this something you’re actually supposed to drink?” She has a point – I honestly believe that the Mhoba High-Ester rum could wake up a dead stick.

But that said, let’s just try to unpack the experience. The rum had lots of impact, lots of edge, little that was gentle, and there was a whole lot going on, all the time. There were whole orchards of different fruity notes contained in that glass, most of which was a little sour, and I can’t say it entirely won me over: in that maelstrom of “everything but the kitchen sink” some elegance, some balance, some drinkability was lost. Still, you can’t fault its complexity and impact, and I completely believe @rum_to_me when he remarked on Instagram that “…it would take over any cocktail in split seconds.”

And also, it does have its adherents and its fans — I’m one of them. Not that I’m a high-ester funky junkie, no, and I don’t actively hunt out the biggest, baddest, bestest with the mostest. But at a time when there’s too much caution surrounding the regular regurgitation of Old Reliables from the Same Old Countries, it’s nice to see a rum maker from elsewhere put out a big screaming bastard like this one, that’s all brawn and sweat with maybe a bit of love thrown in as well. It’s a wildly ambitious, enormously challenging and technically solid rum that for sure will make any list of great white rums anyone cares to put together.

(#900)(84/100) ⭐⭐⭐½

Other notes

- 2025 Video Review is here.

- For supplementary reading, I highly recommend Steve James’s 2019 three part deep dive into the initial releases of Mhoba as well as his company biography, and Rum Revelations’ 2021 interview with Robert Greaves

- So far Rum-X has nine Mhoba high-ester expressions, ranging in strength from 65% to 78%, and average scores from 72 to 87, which is quite a bit of variation. Since all are unaged agricole-style pot-still rums, it suggests that the batch/harvest is of some importance in making a future selection among all these options.

- This bottle is from Batch 2019HE3, Harvest May 2019, one of several from that year.

- As of early 2022 Velier has released two Mhoba rums (both 2017 4 YO expressions), one for the HV line, and one “black bottle” release called “FAQ Plastic.” Holmes Cay out of the US also has a 4YO 59% bottling from 2017.

The Strand 101° was specifically designed by Knud Strand, a colourful Danish distributor who worked closely with Robert Greaves (as he had with many brands before) to bring the Mhoba line to market. What he was looking for was to create a blend of unaged and aged rum from pot stills, adhering to something of the S&C profile but from only one still (not two or more). He was messing around with samples some time back and after making his selections finally came back to two, both fullproof — one, slightly aged was too woody, with the other unaged one perhaps too funky.

The Strand 101° was specifically designed by Knud Strand, a colourful Danish distributor who worked closely with Robert Greaves (as he had with many brands before) to bring the Mhoba line to market. What he was looking for was to create a blend of unaged and aged rum from pot stills, adhering to something of the S&C profile but from only one still (not two or more). He was messing around with samples some time back and after making his selections finally came back to two, both fullproof — one, slightly aged was too woody, with the other unaged one perhaps too funky.

This is where good labelling helps understand what you’re getting. Mine read that it was a sugar cane juice rum, single blended, the bottle outturn (330 bottles, of which this was a sample), batch 2019FC1, South African made, and 65% ABV (ouch!). Actually, the only things missing from the label were the age statement (website says just over a year) and the still of origin (it’s a pot still), which I imagine subsequent labels will correct, especially as additional aged varietals begin to enter the market and a stock of different aged expressions gets built up – already, the company site lists eight different rums, so they’re not wasting any time.

This is where good labelling helps understand what you’re getting. Mine read that it was a sugar cane juice rum, single blended, the bottle outturn (330 bottles, of which this was a sample), batch 2019FC1, South African made, and 65% ABV (ouch!). Actually, the only things missing from the label were the age statement (website says just over a year) and the still of origin (it’s a pot still), which I imagine subsequent labels will correct, especially as additional aged varietals begin to enter the market and a stock of different aged expressions gets built up – already, the company site lists eight different rums, so they’re not wasting any time.

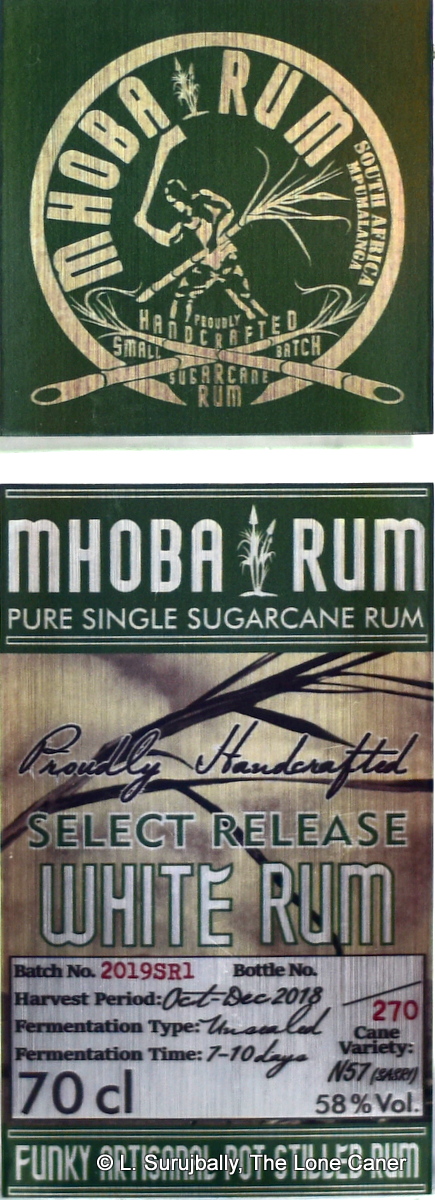

I’ll leave you to peruse Steve’s enormously informative company profile for production details (it’s really worth reading just to see what it takes to start something like a craft distillery), and just mention that the rum is pot still distilled from juice which is initially fermented naturally before boosting it with a strain of commercial yeast. The company makes three different kinds of white rums – pot still white, high ester white and a blended white, all unaged. I tried what is probably the tamest of the three, the Select, which the last one, blended from several cuts taken from batches processed between October to December of 2018 and bottled at 58%. All of this is clearly marked on the onsite-produced label (self-engraved, self-printed, manually-applied), which is one of the most informative on the market: it details batch number, date, strength, variety of cane, still, number of bottles in the run…it’s really impressive work.

I’ll leave you to peruse Steve’s enormously informative company profile for production details (it’s really worth reading just to see what it takes to start something like a craft distillery), and just mention that the rum is pot still distilled from juice which is initially fermented naturally before boosting it with a strain of commercial yeast. The company makes three different kinds of white rums – pot still white, high ester white and a blended white, all unaged. I tried what is probably the tamest of the three, the Select, which the last one, blended from several cuts taken from batches processed between October to December of 2018 and bottled at 58%. All of this is clearly marked on the onsite-produced label (self-engraved, self-printed, manually-applied), which is one of the most informative on the market: it details batch number, date, strength, variety of cane, still, number of bottles in the run…it’s really impressive work.