As the seasons turn and the years pass, the rumiverse edges closer and closer to the hallowed Everest of aged rums, that crowning achievement of geriatric eld grasped and never relinquished (so far) by G&M’s 58 year old rum from 1941. Alas, rums from so far back in time are now a disappearing dream, vanished into blends, collector’s vaults or the gullets of earlier connoisseurs who knew not what they had. There are few, if any, multi-decade old rums from the 1960s or 1950s to be found – these days, it’s the 1970s that is the decade we’re left with, and everything from that era of funk and disco, hot pants, big hair, bell bottoms and the fading of flower power, is a “mere” forty something years old…assuming it’s ever bottled.

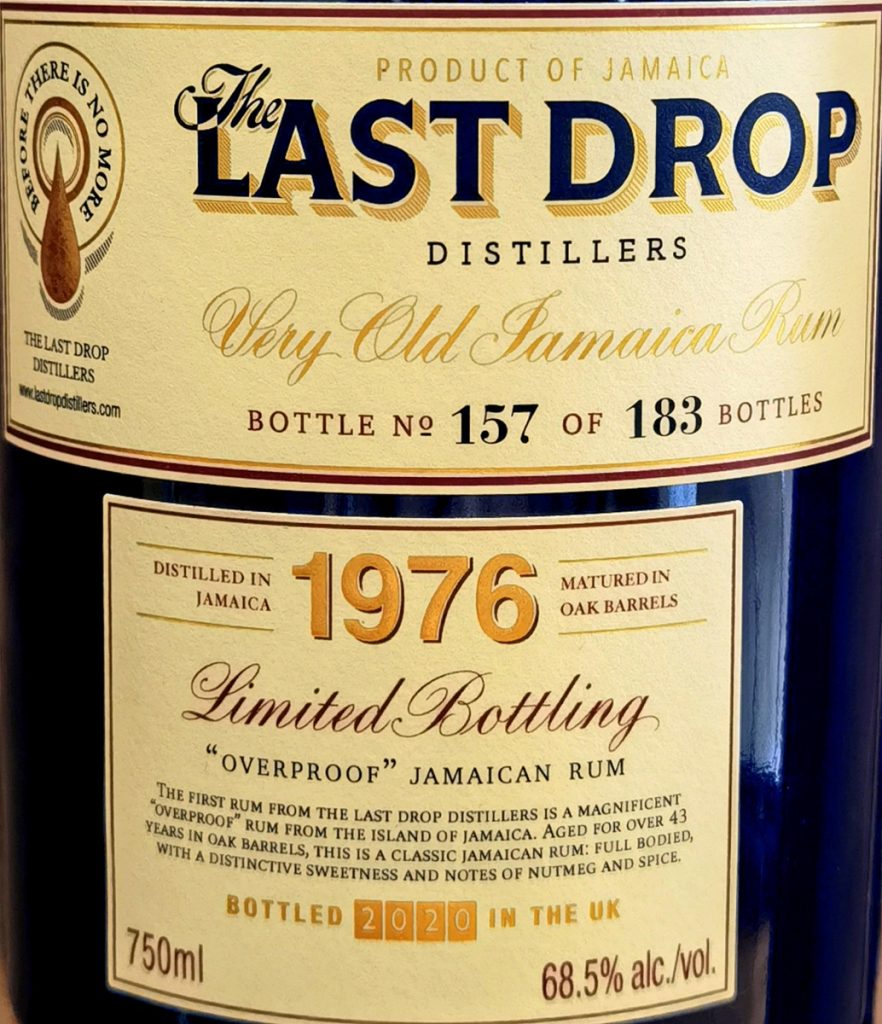

One of these is this rum, a big, bold, rare, practically unknown brown bomber from Jamaica that was laid down the year my family left Africa and arrived in Guyana – 1976. It coyly ignores its own provenance and simply says “Jamaica”, but man, that age is serious, the strength is near biblical, and a sniff of the cork is worth more than my mortgage, so it’s probably best I put a review out there for all those who may one day wonder whether it’s worth forking over that kind of gold for an unproven rum of such mystery. The short answer to that question is “yes” – but only if (a) you are in funds and (b) you really have the interest. Without both these conditions, well, fuggeddabouddit.

So who on earth produced this thing? Where was it hiding all this time? Which distillery made it? What does the tech sheet look like? And – perhaps more importantly – should we even bother? Questions such as these were going through my mind the entire time I was admiring, photographing, reading about and tasting it.

The restraint with which the rum opened is remarkable. It’s 68.5% ABV and aged almost beyond reason, and you’d expect both the power and the lumber to be overwhelming: yet it presents no bite, no scratch, no vicious wood claws, no harridan-like screaming – just a serene, enormously solid flow of firm olfactory notes. Rubber, acetones and honey start the parade, attended by salt caramel and the slightly acrid tang of a warmed-up indoor swimming pool in winter. Aromas of wafers, warm and freshly baked chocolate chip cookies, coffee grounds, and a seemingly never ending parade of all the dark fruit you could name (and a few you can’t) – prunes, dried apricots, plums, sapodilla, kiwi fruit, blackberries and more. And even then it’s not done – one senses the cloying musk of dead bees, melting wax and dusty rooms in old houses, marshmallows and even moist aromatic tobacco. How so much scent was stuffed in here surpasses my understanding but it’s clear that this is one of the most complex and amazing rums I’ve ever tried.

The restraint with which the rum opened is remarkable. It’s 68.5% ABV and aged almost beyond reason, and you’d expect both the power and the lumber to be overwhelming: yet it presents no bite, no scratch, no vicious wood claws, no harridan-like screaming – just a serene, enormously solid flow of firm olfactory notes. Rubber, acetones and honey start the parade, attended by salt caramel and the slightly acrid tang of a warmed-up indoor swimming pool in winter. Aromas of wafers, warm and freshly baked chocolate chip cookies, coffee grounds, and a seemingly never ending parade of all the dark fruit you could name (and a few you can’t) – prunes, dried apricots, plums, sapodilla, kiwi fruit, blackberries and more. And even then it’s not done – one senses the cloying musk of dead bees, melting wax and dusty rooms in old houses, marshmallows and even moist aromatic tobacco. How so much scent was stuffed in here surpasses my understanding but it’s clear that this is one of the most complex and amazing rums I’ve ever tried.

Last Drop Distillers is not, as some alert whisky anoraks will inevitably rush to inform me, actually a distillery, but an exclusive, high-end premium indie bottler. They occasionally – or at their whim – release very rare and very pricey ultra-aged limited edition bottlings on to the connoisseur’s market, and perhaps one of the reasons most of us have rarely if ever heard of them is because we penurious coin-counting rum-hoarding peons are too busy working for The Man to swim around the upscale markets in which Last Drop cruises. They issued mostly whisky, with an occasional liqueur, port, cognac or rum (this one) to round things out, almost all decades old, dating back to the eighties, seventies, sixties, fifties…even the 1920s.

The small company was founded in 2008 and brought together Tom Jago and James Espey, two whisky industry veterans who might at first blush seem to be a little long in the tooth to be setting up new commercial ventures at a time most of us are marking out plots and making wills and feverishly downing our valued stashes before we lose the ability to spell “rum” correctly and start drooling instead of drinking. Yet they did, even though Mr Espery (a veteran of International Distillers & Vintners (IDV), United Distillers & Vintners (UDV) and Chivas (where he was chairman) had just retired at 65 and Mr Jago (who had had a hand in the development of both Bailey’s Irish Cream and what would become Johnny Walker Blue Label) was a sprightly 82. They conjured up this little company where they determined they would source what – by their own lights – would be the rarest and best spirits available.

Riding the increasing bow wave of premiumisation that was just starting to take off, Espey did the marketing himself: no wholesaler was really interested in such small volumes as they were producing, but in the first ten years TLD sold just about all 7,000 bottles of the 11 one-off releases of Scotch whisky made to that point. This finally attracted some attention and in 2016 Sazerac, the American spirits conglomerate which owns Buffalo Trace, bought them for an undisclosed sum in a wave of acquisitions around that time, probably to be a part of its luxury division. A condition of the deal was for the existing release philosophy and management structure to be retained, and both Mr. Jago and Mr. Espey stayed on; the former’s daughter Rebecca Jago, joined the company in 2010 and the latter’s, Beanie Espey, in 2014 ,and when in 2018 Mr. Jago — he was the president at that time — passed away, the ladies were on the expanded board and kept up the same careful pace of exclusive and expensive bottlings.

As of 2023, after fifteen years of operation, there have been a mere 31 releases, making the SMWS rum selections (70+ in about the same timeframe) seem positively profligate. None costs under four figures and since you’re most likely already googling this rum, and because the purse-hunting, gimlet-eyed Mrs Caner also reads these reviews, you’ll forgive me for not mentioning it here.

The taste, in a word: stunning. It presented less as a pure Jamaican rum than a blend of Jamaica and Demerara, and showcases the best of both. There were layers of flavour here,, starting with rubber, nail polish, brine, licorice, honey, vanilla, sweet creamed wafers and the aforementioned chocolate, coffee grounds and salted caramel. In between the spaces coiled the fruits as before – prunes, apricots, overripe oranges and pineapples – and underneath that, one could sense cereals and toast and molasses, even a tang of marmite. And the spices, those were there, light as a dusting of icing sugar on a tart: nutmeg, cinnamon, cumin, cloves.

All of the minor elements on display were chock full of memorable and strange and subtle (and sometimes near-unidentifiable) tasting notes, each of which populated the edges of our awareness for only fleeting moments before another wafted in and around and took its place. They were not the core flavours, the primary notes — those were obvious — but existed to enhance, to supply background, atmosphere, like all those strange characters who move half-unseen and almost unnoticed in the dim corners of Dickens’s or Dostoyevsky’s novels.

And the finish well, what can I say? If this was a movie it would be a four-hour-long extravaganza with a cast of thousands, a bunch of secondary also-rans, two overtures plus an intermission. In short – epic. No other word does it justice, and while admittedly there was little that was introduced at this point that wasn’t already noted above, the amalgam of a basket of ripe and overripe fruit, spices, cereal, coffee, tobacco and leather was a fitting conclusion to a great tasting experience. There are always risks, in a rum this old and from Jamaica, of over-oaking and bitterness and too much reliance on one or other ester-laden note that then ruins the party for everything else and throws the chakras out of whack – not here; in fact, the balance is superb: it is, quite simply, one of the best rums I’ve ever had.

And the questions remain. Which distillery? Everything I’ve researched says it’s a Clarendon, yet for those who are expecting some hogo-laden congener-squirting Jamaican funk bomb from Ago would be disappointed; there are no screaming, rutting esters in play here. Nor, for that matter, does the rum present as a pot still product, and the accompanying red booklet provides remarkably little background here: in fact, it tells us only that it’s from the south of Jamaica. However, Richard Seale, who helped me flesh out the background (see my notes below), in urging caution about expecting a New Jamaican taste profile, also mentioned it was likely from a long scrapped columnar still that once existed at Clarendon but which was later replaced by more modern pot and other columnar stills.

But of course, at this kind of remove, we want the info for our own historical knowledge, and while interesting, it’s ultimately almost unprovable. What’s important is that in knowing it, we see that the TLD 1976 lacks the fierce pungency of Hampden or Worthy Park (which in any case were not operational or laying down aged stock at that time), does not have the elemental brutality of Long Pond (I’m thinking TECA here), and is a ways better than the more elegant middle of the road approach of even Appleton’s older offerings (though the 50 YO comes really close).

It is admittedly somewhat mental to buy the TLD, even with that age and strength and that historical legacy – it’s akin to the Black Tot Last Consignment, and for the same reason. But let’s face it, we don’t really need to. The good stuff is all around us, and there’s oodles of excellent tipple available to our relentlessly questioning snoots and jaded palates, and for less, much less. To some extent what this rum really does is to demonstrate exactly how tasty and affordable so many rums to which we have access already are — modern drinkers are fortunate in the extreme to have such a wide choice available to them.

Yet even with all that choice it has to be said – if only by me – that the Jamaica 1976 is on its own terms, superlative. It’s complex to a fault, tasty beyond hope, balanced beyond dreams, a quietly amazing dram, destined to become a unicorn in its own right, like one of the old Demeraras Velier nervously slipped into the marketplace so many years ago. Somehow – don’t ask me how – I scored a single one of the 183-bottle outturn, perhaps the only one allocated to Canada, which had been sitting in Edmonton for two years gathering dust, ignored and passed over. Did I regret it? A little. Did I save it? Not a chance. This one is all about cracking, savouring…and then sharing.

(#1000)(93/100)

Other notes

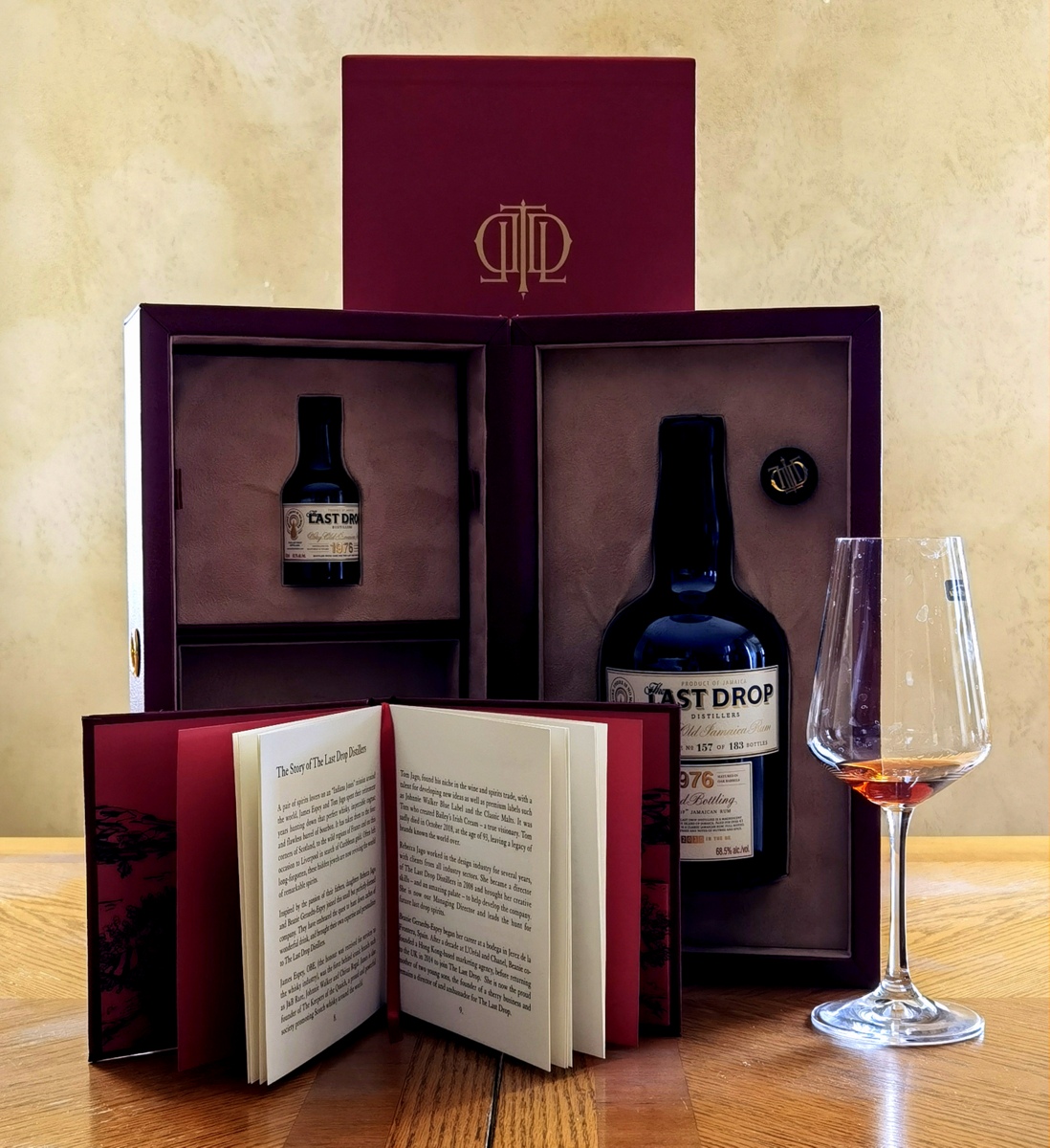

- The presentation of the bottle is first rate. Red leather box, embossed logo, extra cork, a book of small details about the company and the rum – and two bottles, one small 50ml mini to play with and the full sized bottle.

- My sincere thanks to Richard Seale, who took time out on two separate occasions to answer some questions and provide context and background. He is on the tasting panel for the Last Drops Distillers and apparently enjoys the experience enormously.

- My appreciation also to Matt Pietrek who helped me check on some historical details.

- There is no information as to where the barrel was sourced. URM in Liverpool, maybe, but I somehow think this is one of those rum barrels some whisky outfit had squirrelled away someplace. Just a hunch.

- Are there any other rums like this, from so far back, still ageing in any bottler’s portfolio? Unlikely, unless some of the old Scottish whisky houses are holding on to old barrels in dark cellars, unseen and maybe even forgotten by mere mortals. Richard suggested that there won’t be, either. There was a three year minimum age rule in play for whiskies since around 1916 that was also adopted by rum makers, so the incentive was to either release relatively young aged rums or send bulk abroad; and only after that rule was relaxed in 1973 or so, was there a gradually emerging market for single barrels. This, he theorises, is one of the main reasons why there are almost no bottled single barrel uber-aged rums in existence pre-dating the 1970s, and even the oddballs of the Cadenhead 1965 Guyanese rum, or the 1941 Long Pond, may just be the rare exceptions that prove the rule.