“Only one human has ever defeated a Minbari fleet in battle. He is behind me; you are in front of me. If you value your lives, be somewhere else.” Ambassador Delenn of the Minbari to Earth Alliance attack fleet, Season 3.

When Ambassador Delenn utters these words after a major space battle, and at a time when it seems utter destruction of Babylon 5 is imminent and despair abounds, one can barely resist jumping on the couch and doing a clenched fist “yeah!” Which I’m sure you’ll admit is not a common occurrence in TV dramas of any kind, and it says something about the emotional power of this often overlooked sci-fi series. Because Babylon 5 created a world so immersive, storytelling so strong, identification with the characters and narrative situation so remarkably complete, that one felt an energy and emotional connection to its characters, similar to that which Star Trek fans had for Mr. Spock, say.

The show, which ran for five years between 1993 to 1997, was a sprawling, operatic indulgence in world building, as seamlessly constructed as the Star Trek or Star Wars universes, and positioned itself between the character-driven style of the former and the grand themes of the latter. What it also did, and which is not generally acknowledged, was to point the way towards the golden age of long-form television through which we are now living.

In the years before (and during, and after) it aired, the episodic formula of TV was alive and well and had been the standard for decades. One could watch a series, or jump into it, at pretty much any point and miss nothing. Characters in such series were often very similar from one year to the next, few showing any kind of massive variation, let alone development. Of course, daytime soaps were plotted over many years, but they ground on in a kind of never ending continuity that replaced old and resolved situations with new ones (or twisted the same old ones into new shapes); in contrast B5 was envisioned from the very beginning as having a five year story arc, to be shown over five seasons, with each season telling the story of what happened in a calendar year. Long term planning was done at the inception, not as the show went on, and this allowed storylines or character arcs that were set up in Season 1 or 2 to not be crucial, or developed, or resolved, until much later in the series (which fortunately allowed the show to skate over some occasionally weak writing and pacing problems).

In this way it was miles ahead of more popular pop-cultural icons where the creators seemed to make things up as they went along, without a clear end game in sight, and pointed to a viable alternative to episodic television where one could jump in at any time and never get lost. Eschewing this format and sticking with the long form, J. Michael Straczynski (JMS from here on) plotted out his epic completely, and moved seamlessly towards his conclusion so well that he was able to weather the loss of a lead character in Season 1 and the near-cancellation of the series in Season 4 and still manage to continue the series and bring it to a proper end a year later.

***

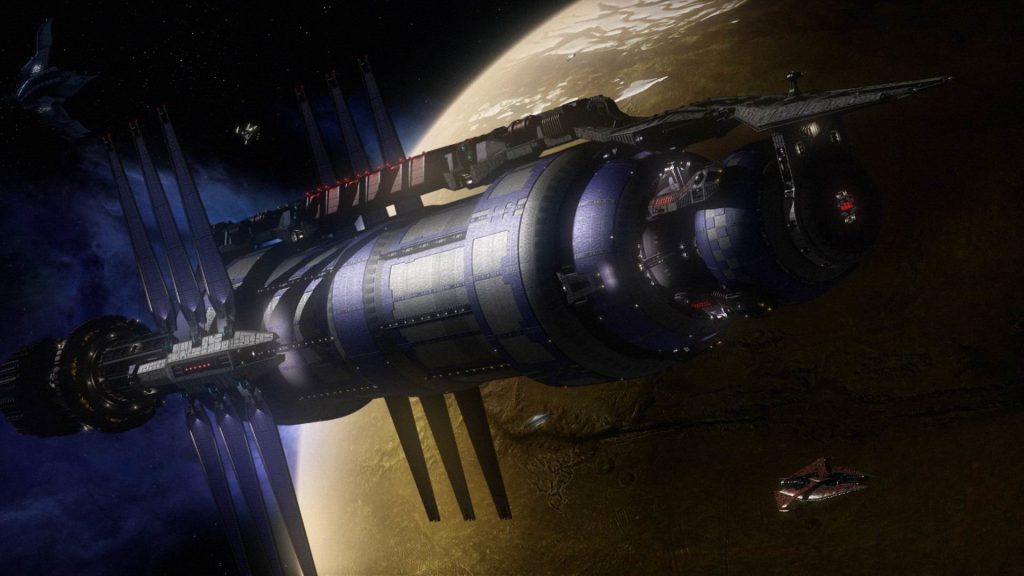

To summarize the plot is difficult, but let’s do what we can. Set in the 2200s, the B5 galaxy consisted of various space-faring races. Humans, of course. An older, and somewhat more technologically advanced race called the Minbari who were deeply ritualized. Two other major races were the Centauri (modelled after a mix of ancient Rome and revolutionary France with crazier hairstyles), and the Narns (humanoids with brown skin and leopard spots who had been conquered by the Centauri and who had only recently won their freedom and were now expanding aggressively). These two, exemplified by their respective ambassadors, were highly antagonistic towards each other and were joined by a League of Non-Aligned Worlds made up of a number of smaller spacefaring races who in turn provided backdrop, and swelled an episode or two here and there. And lastly, there were the mysterious Vorlons who were far more technologically advanced than anyone else…but about whom nobody knew much, since they always wore “encounter suits” to hide their appearance and prevented excursions into their own space.

Ten years before the events of the series in 2258, there had been a major war between Earth and Minbar in which almost resulted in the annihilation of the human race before the Minbari inexplicably surrendered on the cusp of complete victory. At around the same time the Narns rebelled against the Centauri Empire and won their freedom – the two remained bitter enemies ever since, fighting inconclusive skirmishes and jousting for influence and power with the lesser races. After the chaos of the Earth-Minbari conflict, it was decided to set up a space station in neutral territory to act as a sort of United Nations of the galaxy to prevent future carnage. Babylon 1, 2 and 3 were either sabotaged or destroyed, and B-4 mysteriously disappeared twenty four hours after going operational. At the beginning of the series, then, tensions, while remaining high, were managed in a sort of uneasy, fragile peace. But gradually that peace was beginning to unravel, and a strange new race of enormous hostility and destructive power (they were appropriately called “the Shadows”) was moving quietly, building allies and interfering in the agendas of the races to deliberately provoke conflict. Wars large and small were breaking out everywhere, and simultaneously there were problems on earth as a sinister group of (Earth) Government telepaths called the PsiCorps came to power behind the scenes, and Earth began to slide into an Orwellian dictatorship after the assassination of the president at the end of Season 1.

Over the course of the five seasons, all major and many minor characters were drawn into the great war that the Shadows unleashed, and their personalities and lives were altered in often surprising, unexpected ways. The ambitious Centauri ambassador Londo Mollari became Emperor but found redemption, his mortal enemy G’Kar became a revered spiritual leader, the Minbari ambassador Delenn changed her genetic makeup and found love, and the station Captain became a commander, a general and a statesman. The station Doctor found humility, the Commander of the station unrequited love, the Security Chief became a businessman. And such developmental arcs were not limited to the small “main” cast, but given to many other smaller roles that in other shows would have not received such depth of treatment (as G’Kar notes presciently in season 1, “Nobody here is exactly what they seem.”) The Vorlons and the Shadows have their rationales, twisted as they may be. Alfred Bester the PsiCop is a smirkingly evil sort-of villain played by Walter Koenig (better known as Ensign Chekhov) has appalling yet also rational reasons for what he does; Talia Winters the telepath reveals a depth of humanity not immediately evident; Vir Cotto grows from a bumbling idiot in the first season to his boss’s conscience (and later, emperor himself); a throwaway Narn character from an earlier episode becomes G’Kar’s bodyguard, and later disciple. A Minbari warrior leader utterly opposed to Ambassador Delenn proves to have greater depths than suspected. And so on.

All this is played against a technological setting that actually makes sense. Faster than light travel is accomplished by the use of “jump gates” or “jump points” which serve as conduits to hyperspace, a concept so ubiquitous in science fiction that one can hardly fault the creators for not looking for something more original. Babylon 5 creates gravity for itself by the use of rotating sections, which is scientifically sound. Medicine, weapons, computers, spacecraft and communications are similar to our current world, just made a little more advanced for the setting. Time travel is treated with respect and is organic to the story, not just some quick one-episode trick. It’s perfectly believable all the way through. Moreover, there is a backdrop of galactic history here — of empires risen and fallen, of old races and young ones, differing cultures, religions and mind sets — that is nicely integrated into the overall tapestry of the core story.

Babylon 5 suffered by being – inevitably – compared to Star Trek, the other sci-fi TV series that dominated the channels at that time. ST: The Next Generation copied the episodic format of the Original Series (as did Star Trek Voyager which premiered two years later); and in concept B5 was more like Deep Space 9, which was often thought to be a rip off of B5. To some extent the B5 Universe is different in conception and execution from that more famous creation, however. The emphasis was on grand movements of galactic history and the shift of people’s characters over time; of politics, religion, fanaticism, rise, fall, strength, weakness, honour, love, hate, good, evil. And indeed, the B5 characters were more flawed, much less noble, made mistakes, suffered enormous tragedy, in a way the many other universes simply never explored (“The City On The Edge Of Forever” episode from ST The Original Series probably came closest). The social constructs were grittier and less rosy; war was considered almost a normal state of affairs, as was poverty and prejudice; and the different races had distinct personalities and religious beliefs that were fleshed out over a long period. Even the special effects and production design were different, giving the show a look and feel that quite original (though by today’s standards, primitive). In its examination of smaller, greater and even galactic themes, it pushed the boundaries for science fiction in ways that had not previously been done, and if it had been, then nowhere on this scale or (I argue) this well.

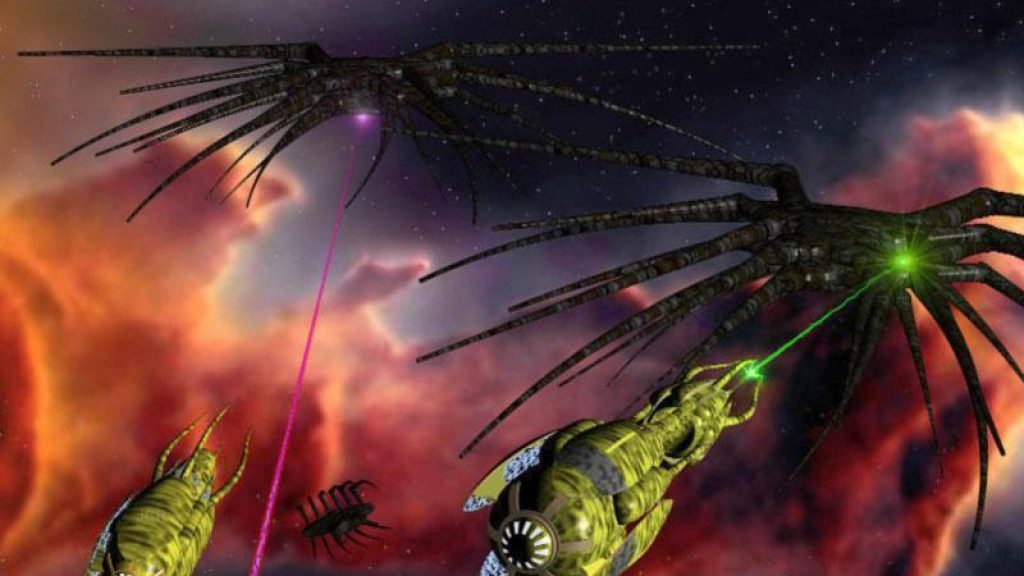

Certainly there is a derivative feel to the series. Behind the sweep of storytelling of empires rising and falling, wars won and lost, characters suffering love or loss or death, lie the great archetypes of our historical storytelling tradition. The hero on a quest, the lady fair, the venerable teacher who dies, evil villains and creatures and deeds most foul. Reality while adhered to, often takes second place to visual momentum: I mean, consider the Shadow vessels – in no way can they be termed logical in design (one wonders where the crew, if any, bother to sit, or where they fit into the fighters), but man, just look at them. They are instantly recognizable as evil, and may actually be the scariest warships ever seen on TV. So, who cares about the practicality? They work at the level of our subconscious race memories, where we fear the darkness and creepy crawly spiders.

In its influences, some are quite clear. Christian motifs are quite obvious, and plentiful. JMS took much inspiration from the Lord of the Rings: the Third Age, the Rangers, the Shadows, Lorien, Zahadum (a play on Khazad Dum), as well as a hero who falls to death there and is revived by a greater and older power, the uniting of two long sundered branches of life by a marriage in the present (like Aragorn and Arwen)…and with many other small details that are a wink to Tolkien. There are also references to Arthurian legend, as in the naming of Mr. Morden, Exacalibur or the episode “A Late Delivery From Avalon”. JMS named his series after the Baylonian creation myth and the conflict between order and chaos, not only in the show’s title, but in the opposing philosophies of the two great older races. Shakespearean quotations are sprinkled throughout. The great machine of the Krell from “Forbidden Planet” is winked at. A nod to Alfred Bester’s novel “The Demolished Man” is there for those who are familiar with sci-fi and Earth’s slide to a surveillance state echoes “1984” quite obviously.

***

If the show had weaknesses, one of them was certainly the lengthy setup in Season 1 which required far too many standalone episodes that did not always fit neatly into subsequent seasons, and the loss of Michael O’Hare to illness forced the removal of his major character and replacement with the talented Bruce Boxleitner, who at first seemed too boyish for the role but inhabited it so well it’s impossible to think of anyone else doing it. Season 5 had a tacked-on feel mandated by the show’s near cancellation in its fourth year, so JMS had to truncate several storylines and telescope others. Claudia Christian, another major character, left the show at this time, and all these issues meant that some continuity was unavoidably lost. Essentially, Season 2 through 4 were the core of it all, and remain the most watchable, the most riveting — with 1 and 5 more like essential bookends required for full understanding but not as enjoyable. The important thing to understand is that individual episodes might be problematic, but taken as a whole, there is a remarkable sense of JMS knowing exactly what he was doing every step of the way.

I also argue that for all its pacing problems — certain aspects of the long story take too long to set up and are resolved too quickly, or unsatisfactorily, though fortunately the whole remains strong – that the series managed to maintain coherency and consistency under these pressures, and still manage to deliver on 90% of what its creator envisioned, is some kind of miracle in modern TV entertainment. Unfortunately, unlike the other two franchises mentioned, B5 never really succeeded in becoming a touchstone of modern culture. Perhaps this was because it was too ahead of its time, and in its own way, perhaps even too quirky. Producers feared to alienate audiences who could not come in at any point and know what was going on (as they could with Star Trek). B5 was a show that required continuous viewing over a long period in the days before Netflix and DVDs and binge watching whole seasons.

The show did however spawn a number of TV movies (the best was a prequel called “In the Beginning”) and even a spinoff series called Crusade, which was cancelled before it even went on TV, though thirteen episodes had been filmed and eventually aired in 1999. Babylon 5 had a life in comics, novels and games, the last of which it could be said to have influenced rather more than any of the others. But nowadays I think it’s been relegated to a second tier production that lives on in occasional syndication but without the cultural impact I felt it could have had if, say, it came out now (which is unlikely). Another twenty years, it’ll be forgotten except by older fans.

It’s possible that a show like Babylon 5 may never be made again. Star Wars and Star Trek can work within their visual and cultural parameters precisely because of their near unassailable position in pop culture and the collective consciousness of the audience. But other sci fi series have a harder time of it. Battlestar Galactica went the route of realistic “hard” sci-fi and was one of the better ones, partly because of superior special effects and partly due to a solid multi-year story arc with a clear ending. “The Expanse” is another, perhaps even better – it’s also long-form in nature. But Babylon 5, with its grand themes is less on a level with those, lacks their hard-core engineering reality – it’s part of a myth pool, and cheerfully plunders mankind’s darkest fears, its earliest legends, its most powerful and enduring stories, to weave a complex tale of its own. The shakiness of its special effects to modern eyes, its occasionally poor writing, and its failing in comparison to other sci-fi series, should never blind one to either the trail it blazed for TV sci-fi, or the overall narrative excellence it displayed. I still think it’s one of the best of its kind ever made, and maybe that’s why I watch it without regret, shame or apology every few years from start to finish. My family regards this exercise in self-indulgence with a sort of he’s-at-it-again patience, but what the hell, it’s just that kind of experience.

Some references and additional notes

- Nardi Views has some nice essays that go into deeper depth than I have the time for https://domnardireviews.wordpress.com/tag/babylon-5/

- Wikipedia of course https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babylon_5

- Some Community links are here http://www.isnnews.net/babylon5/community/links.shtml

- An “oral history” article is a good reference

- In August 2018, (after I finished this essay) it was announced that Warner Bros. would reboot the series.