Once again we are visiting India, to look at a rum made by the world-famous whisky producer, Amrut Distillers. The story of this remarkable company has been told already so I won’t rehash it here — but it behooves us to note that for all the ballyhoo about its whiskies (for which it is mostly and justly famed), Amrut has been making rums for far longer, dating back to its initial establishment in 1948. Also, in a departure from Mohan Meakin (of Old Monk fame), Amrut did not descend from a British-run company from colonial times, but was and remains entirely home grown.

In years past I have looked at two rums from the company – the Old Port Deluxe, and the Two Indies rums; however, this was many years ago, and as I lurch obliviously into doddering and drooling dotage, my memory fails sometimes, so I’ll revisit those — or their current iterations — soon. Today, however, we’ll fill a small gap in the minimal company rum stable, and review the Two Indies White, which I found at the 2024 Paris Whisky Live — this edition was issued in 2023 — displayed with a complete lack of fanfare off to the side of more famous whiskies, on the ground floor booth of the company.

“Two Indies” is a moniker given to show off the rum’s antecedents from distillate produced both in the India (the east Indies), and the Caribbean (the west). The white rum is made somewhat at right angles from the two Two Indies variants, original and Dark, which both have at least three Caribbean components (Jamaica, Barbados, Guyana) to add to the Indian part. This one has some Jamaican rum – the distillery is never mentioned – added to a blend of Indian made sugarcane juice rum and jaggery-based rum.

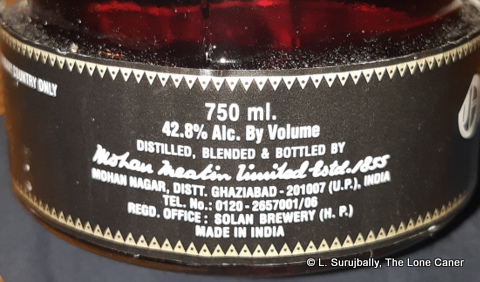

The source of the juice is the Bangalore facility where the company HQ is also located, from cane grown in their backyard, and the jaggery1 is sourced from India’s sugar city of Mandya, SW of Bangalore. All three parts are pot still distillates, which, after being made, are blended and aged for a short eight-months-to-one-year period in ex-bourbon casks. And, as is usual for India, it’s released at 42.8%, which is the Imperial 75 proof from colonial times that was never abandoned.

The source of the juice is the Bangalore facility where the company HQ is also located, from cane grown in their backyard, and the jaggery1 is sourced from India’s sugar city of Mandya, SW of Bangalore. All three parts are pot still distillates, which, after being made, are blended and aged for a short eight-months-to-one-year period in ex-bourbon casks. And, as is usual for India, it’s released at 42.8%, which is the Imperial 75 proof from colonial times that was never abandoned.

Although I’m sure the intentions were well meant, the rum noses as thin and weak. Initially one can sense candy floss and marshmallows, plus some light white fruits (pears, watermelon, papaya), some sweet coconut water, leavened with bananas, caramel, and some lemon zest. Behind all that are wisps of vanilla, cinnamon and cardamom, which one has to really strain to notice at all. One wonders where the Jamaicans are hiding, because weren’t they there to provide some oomph and kick and attitude? Doesn’t feel like that at all. And the distinctive aggro of a pot still product is decidedly muted (if not absent altogether), which is disappointing, to say the least.

This general sense of puling wimpiness pervades the palate as well. The website and promo materials talk about a “herbaceous” and “vegetal” profile, which I ignore, because it certainly doesn’t taste that way. Oh, we have some easygoing pears and guavas, an intriguing series of notes that channel fresh Danish cookies and pastries, and a light set of spices, but the crisp grassy notes of a true agricole are not in evidence. On the contrary, it’s underpowered and the profile suffers for that; this thing needs to be stronger, otherwise the whole thing, including the finish, is like unsatisfying coitus — brief, barely noticeable as an experience, and by the time you get a head of steam going, it’s over. There are some light fruity notes and a bit of spearmint gum as consolation for disappointed participants – I guess that’s something.

Granted the rum is relatively cheap and made for the cocktail and backbar circuit (it costs about €30), so as an interested reviewer I guess I’d buy it, try it … and then trade it or sample it off. The low strength and general youth and lacklustre profile are not to the rum’s advantage, and whatever the Jamaican portion of the blend is — on the website they stated it was added to “infuse the blend with its powerful, fruity esters” – it’s too little to put an exclamation point to the rum’s taste. It tries to take the best of three different rum styles, and succeeds at none of them, which suggests to me that perhaps it would be better to try and keep the rum as a pure Indian expression rather than try and jazz it up as some kind of exotic blend. Keep this rum on the bar as a mixer if you want, but me, I’d keep it there for something to juice up a cocktail, nothing more.

(#1102)(75/100) ⭐⭐½

Other notes