Ray Bradbury is a twisted Isaac Asimov, a literary Dali who painted with his words, a Stephen King before Stephen King was there. If King is the master of the occult, of horror, and of long novels and deep characterizations playing “what if?” with the universe, then one of the wellsprings of his imagination was surely the taut, tightly wound dystopian short stories penned by his prolific predecessor. And indeed, how much of our subterranean mental landscape has been formed by this one man, a contemporary of the early 20th century dime novels and pulp fictions with which I am so in love? In Bradbury we see a Golden Age of horror fiction even before it became respectable, a right turn from the prevailing “hard” sci-fi of the day — and yet, even to use such terms shortens and simplifies an enormous body of work encompassing sci-fi, fantasy, horror, mythology, psychology and fictional futurism. Categorizing the man and his output is like trying to nail down Asimov, or King – it’s too much to encompass into a single sentence. To the extent that there is s cultural mythology of the twentieth century, a sort of inner world of our imaginations, surely Bradbury is one of its creators.

Bradbury – and if any of us do not know his name by now we cannot call ourselves book lovers – is one of the masters of the short form. Few of his short stories exceed fifteen pages in length, and are as tightly wound, as clear of expression and as dense in imagery as anything penned by King in his beginnings, by Asimov, Heinlein, Robert E. Howard, Elmore Leonard, Dashiell Hammett or any of the myriad others who dabbled in the field (even Bradbury’s novels – The Martian Chronicles, or Dandelion Wine, for example – are short story collections in disguise, and Fahrenheit 451 began as The Fireman, a short story). And yet, unlike these straightforward writers who are mostly plot – and I don’t mean this in a bad way – there is always something off-kilter and distorted moving beneath Bradbury’s work…something badly reflected, like a mirror with a flaw one can sense but not always see.

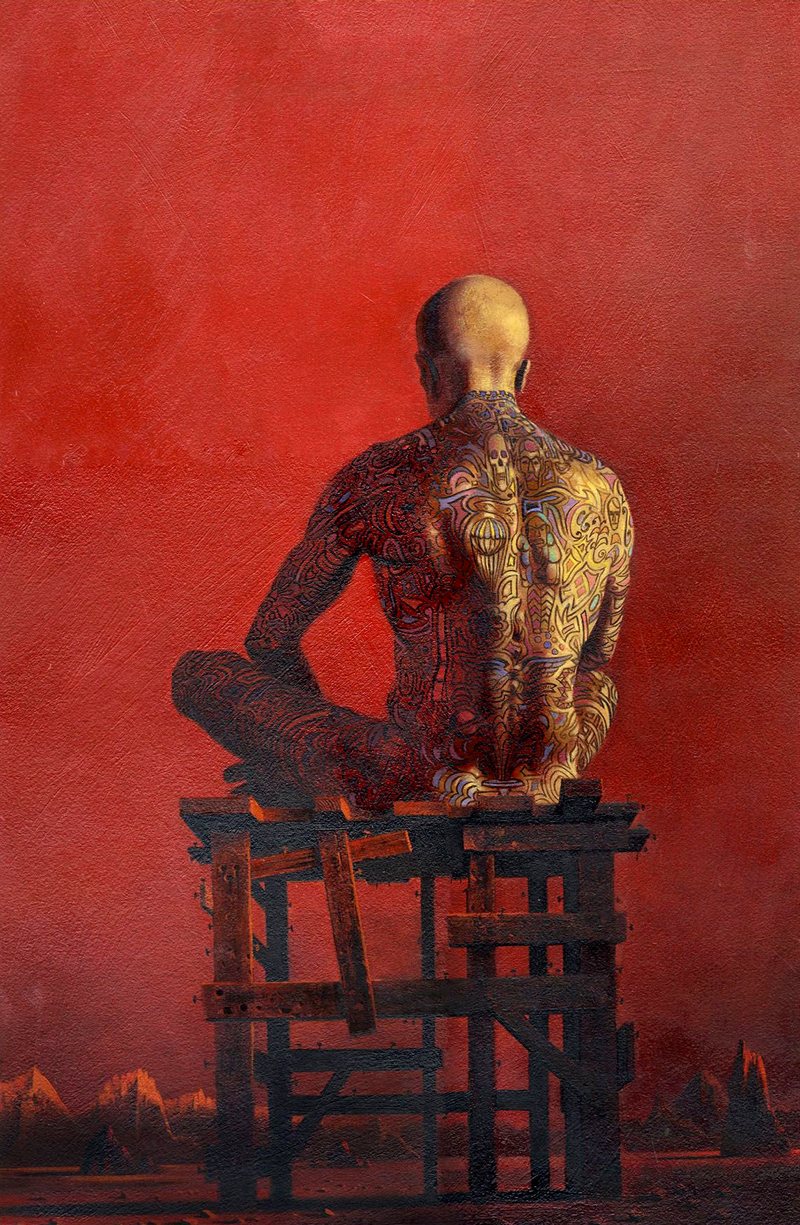

While I have read most of his collected works over the years, long and not-so-long, the ones to which I keep returning in order to sip at the well of his genius, are always the short stories of The Illustrated Man, “100 Celebrated Tales” and The Martian Chronicles. In the best of these, there is always a haunting sense of time and place…of America gone sour, perhaps, or of strange places in our memories, or even places that never were. And that feeling of almost – but not quite – recognition, like acquaintances long-forgotten who we feel we’ve met somewhere before.

Consider “A Sound of Thunder” – it combines time travel, a hunting safari, politics and chaos theory….how stepping on a butterfly irrevocably changes the course of history. Or “I Sing the Body Electric” which is only nominally about how a man brings a robot granny into the house to comfort his grieving children after the death of his wife. Or the creeping sense of horror about “The Playground” (which could have been written by King), where a man who changes places with his son to spare the child the cruelties of childhood, only realizes at the close how cruel childhood really is. There is the depth of psychological suspense in “The Veldt” where kids plot to murder their indifferent parents in a Star-Trek-type holodeck meant as a play area; and one of the most clearly realized, utterly atmospheric alien-worlds stories ever written, “The Long Rain”.

Bradbury’s work in sci-fi seems occasionally dated, but he himself argues that he doesn’t really write science fiction (at least not in the engineering style of “Red Mars”), but fantasy, because his worlds cannot exist, unlike those of the realists like Asimov and Heinlein. The reason his work still resonates, even after more than half a century is less because he wrote about futuristic rockets, robots or machines, than because he described people we can recognize – and how the development of the soul-annhilating techno-society he so clearly foresaw alters the way we think, the way we interact…who we are. He is a mordant ethicist who argues for humanity while pointing out how much more human our creations can become…and how little can be left in us if we are not careful.

Think of how “The Murderer” so acurately predicted our mad “always-connected” culture with his brilliant paragraph: Three phones rang. A duplicate wrist radio in his desk drawer buzzed like a wounded grasshopper. The intercom flashed a pink light and click-clicked. Three phones rang. The drawer buzzed. … The psychiatrist, humming quietly, fitted the new wrist radio to his wrist, flipped the intercom, talked a moment, picked up one telephone, talked, picked up another telephone, talked, picked up the third telephone, talked, touched the wrist-radio button, talked calmly and quietly, his face cool and serene, in the middle of the music and the lights flashing, the phones ringing again … Substitute an i-phone, laptop and TV and you’d have a picture of how my daughter spends time in her room.

And always, coiling underneath the spare plotline, is the dark side of Americana, in stories like the one where a child wishes for everyone in the world to disappear…and they do; of machines that stand around telling stories of the men who made them, now long extinct; of a man hurtling in space to his death, wondering what he can do “to make up for a terrible and empty life” before dying; how the Rocket Man wanted to be with his family when in space, and in space when with his family.

Bradbury is neither a Luddite nor a pessimist. Nor for that matter is he an optimist. He simply invites us to be alert to the consequences of our actions. He is realistic enough to know technology is not the answer simply because it can clean your house and create a robot replacement for you; just twisted enough to see the hope of machines wanting to act like humans will be overhsadowed by humans behaving like machines; and cynical enough to understand – and make us shudder at – the irony of youthful innocence reposing in adults while children are the amoral, devious homicidical crazies we ourselves allowed to be, and which we should fear. In the richness of his storytelling we see all the possible reflections of ourselves, all the permutations and possibilities of our society: we read his terse and evocative prose with appreciation and amazmenet and wonder…his stories take up residence in our minds. We know them, we love them, we dread them.

“There would be no King without Bradbury”, Stephen King once remarked. Maybe so, although he admits elsewhere to being as influenced by Lovecraft and Wheatley and pulp as by that old master. Be that as it may, it is thanks to Bradbury that we have an enriched body of often unappreciated, undeservedly low-rent work without pretensions of grandeur, that will stand the test of time — and which has become, somehow, part of the iconic literature of our age. If I were to think of which short stories out there I’ll be reading in the twilight of my life, when hope, realism and cynicism have taken equal residence in my heart, then I’ll pick Asimov, King, Heinlein, Naipaul, Lahiri, perhaps half a dozen others…and Bradbury for sure.