Introduction

If ever there was a hook, a cachet, a point of distinctiveness, something that set apart an independent bottler’s rums from the pack of baying pretenders, surely the SMWS has nailed it. Here is a bottler of primarily whiskies, that does no advertising, issues barely any rums, and yet whose rum-cred can be said to be up there with any of the Big Names. And this is in spite of their relative obscurity and rarity, and their cost. Their rums are never available on supermarket racks, only on the shelves of its own Members’ Rooms, its partners or online — plus, you have to be a member to get one, and pay for the privilege then too. Quality-wise, I can’t speak to their whiskies, and I wouldn’t go so far as to say the rums are on a level with the mastodons of our world – but their reputation even so is nothing to sneeze at.

That reputation rests partly on the distinctiveness of the tall green bottles which embrace the various rums – in my experience only Velier has anything near to this kind of presentation and then only with the main lines of the Habitations, the Demeraras and the Caronis. Then there is the Society’s marketing masterstroke of never saying which distillery produced the liquid inside, just a number, which drives newbs into transports of ecstatic confusion as they dive in to the lore of the Society and start to do their research. And lastly, perhaps most tellingly, are their bottle labels, which have not only gotten more informative (within the limits of the distillery obscuration noted above) – but also more amusing. I challenge anyone to tell me what some of their evocative titles mean, and yet, who can blame them for such a method to their madness? For, once seen and laughed at – or even agreed with – who could possibly forget?

That said, for an independent bottler as renowned as the Scotch Malt Whiskey Society (hereinafter referred to as the SMWS, or the “Society”), it is peculiar how little is known about it in the rum world. Oh, whisky fans certainly know of it, and I have several friends in the rumisphere who are members, but general rumfolks? Less. And yet, it’s not an old and proud production house dating back from the quiet halcyon days of Before, from the days of Scottish bottlers of the 1950s, or Italians in the 1960s or the rum torpor of the 1970s when Bacardi ruled all with a light-rum mailed fist. It was formed, quietly and without fuss, in 1983 and based on many of the same desires and reasons that inform the modern marketplace for indies.

Beginnings

Phillip “Pip” Hills (c) SMWS

As with many such organizations we have covered in the Makers series, the Society began as an idea in the mind of one man, Phillip “Pip” Hills, a tax consultant. Raised in Grangemouth close by Falkirk, he grew up knowing pretty much only blended whisky, which he didn’t really care for. This was in the 1970s, at which point scotch whisky was in the same doldrums as persisted in rum until the mid 2000s – blends were everything, cask strength the exception, and each brand went for long term taste stability. Fortunately for his taste buds, two of his friends had a farm way up north, next to a gentleman who would on occasion buy quarter casks of Glenfarclas from George Grant, and passed samples (supposedly filtered through a towel, goes one – disputed – anecdote) around generously — and those tastes from the cask that Hills tried were so entrancing for him and his own friends with whom he shared it (or to whom he spoke to about it), that they pooled their resources, and had him get in touch with Grant. He was lucky enough to fill in the spot of one of their “regulars” who had had the misfortune to pass way without passing on his annual cask allocation, and managed to buy that quarter cask for £2,500.

Clearly those people who came together in Edinburgh to get their share of that first cask didn’t stay silent, because subsequently, complete strangers would stop Hills and ask him to participate in his next purchase. This was sufficient for him to go back to Grants for two more casks, and the network effect of the participants over the next years was sufficiently strong for Hills to realize he was onto something. He felt that these whiskies were way better than the bottled blends, and if this expanding group of middle-class professional folks which comprised the buying circle – the syndicate – were turning into such aficionados, then perhaps selling single cask bottles on a more formal, paying basis was a good idea.

To do that he required an entry into the commercial whisky world, and as luck would have it, a fellow climbing enthusiast introduced him to Russel Sharp, also a climber, who at the time was head chemist at Chivas, responsible for quality. Sharp gave him a primer on the difference of the cask whiskies from bottled fare, and remarked that even if he (Hills) were to try doing this kind of semi-private bottling, legal issues such as trademarks would prevent him from using distilleries’ names on the labels. Though, he didn’t feel there was a market for it, as did all other contacts within the “regular” whisky world with whom Hills later got in touch.

Photo (c) OldLeith.com – The Vaults, when JG Thompson owned it.

The syndicate — including Hills, actor Russel Hunter, contractor David Alison, playwright W Gordon Smith and architect Ben Tindall — was incorporated into the Scotch Malt Whisky Society Ltd in 1983, with Gordon Smith, who wanted the position, installed as Chairman of the Board, even though Hills made it clear it was a co-operative sort of undertaking since all had equal shares. The Society had the mixed blessing of being able to buy the premises of J.G. Thomson (a wine merchant) called “The Vaults” which were to be vacated as Thomson moved to Glasgow (the top two floors were condemned). It was acquired by contributions from these members of the syndicate, but as it required major repairs and upgrades, by the time restoration was done they had all lost their investment – however, by then the Society was doing very well via its membership dues and bottle sales, so it’s a fair bet nobody lost their shirts, and the SMWS continues to operate from that base to this day (note: for further background reading on the The Vaults, see here; and for JG Thompson’s history, here.)

Having premises, a registered society, members and a mandate, Hills now required product, and went around to the distillers of the day to source casks for the Society releases. This was a time when many distilleries – Port Ellen, Glenugie, St. Magdalene and Brora are some examples – were closing and others were in dire financial straits, so there was no shortage of excellent casks to chose from. But he also found, not entirely surprisingly, that operating distillers at that time saw themselves as only expert selectors, suppliers of quality ingredients to make trademarked blends of consistent profile, rather than individualized whiskies with their own special distinctiveness and quality — which is very similar to the way Caribbean rum makers, until very recently, rarely saw their own rums as unique, or their estates’ production as selling points in their own right. This then allowed Hills to go around and buy casks which did not match the profiles for the blends the distilleries participated in, did not know how to market, and wanted to get rid of. And, perhaps as important, to get them for reasonable prices based on liters of pure alcohol per year aged, not in any way related to the cask, its type or provenance, or the quality of the whisky itself (a situation which would seem utterly insane today, for any quality spirit).

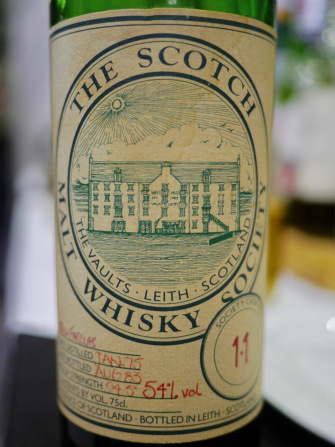

Release 1.1 with handwritten details by P. Hills

Product in hand — 1.1, the first one, was a Glenfarclas 1975 8 YO sherry cask and there were also 2.1 (a Speysider) and 3.1 (an Islay) — bottling came next. Fortunately, there was a small bottling plant in Commercial Street (a few corners away) which agreed to do the necessaries. It was decided to preserve an old fashioned, antique ethos to the appearance, and so green bottles were selected (these were common in the 1950s but being phased out by the time the Society was formed, and so also available at a much more reasonable cost). All four of the initial outturns were provided, then, in March of 1983; regular expressions were planned to be released monthly thereafter, and that has been going on almost without interruption ever since.

Hills and the first members were prepared to market the enterprise, figuring the quality of what the Society was offering in exchange for membership would more than speak for itself – but as it turned out, he got help: one of his business partners knew the food and wine correspondent for The Scotsman newspaper and it was suggested that a whisky tasting be organized for him and his journalist friends (although the focus of their writing, for the most part, had been wine). Hills mentions this tasting with fondness as a seminal event, possibly the first of its kind, and certainly Mr. Wilson wrote a sterling encomium of the drams he had tried, not just after that first tasting in 1984, but again a year later. I do not doubt that the word of mouth engendered by those well-connected media personages, and Wilson’s pair of articles, must have more than paid for the cost of the tastings.

That first session turned out to be such a success that the format was copied for the initial get together of the Tasting Committee, held in the kitchen of Hills’s house in Edinburgh, and he rather ruefully admits that it was a “motley bunch”. On paper, there was nothing wrong about getting together a set of people who worked with words and knew whisky – the committee included a historian, a professor of Celtic Studies, a professor from LSE among others – but the vocabulary simply wasn’t there (that took time to be developed – another similarity this story shares with rums) and so the quirky characteristic of the Society, that of metaphorical descriptions, was born that evening. That said, in the years that followed, Hills often wrote his own tasting notes, and the insouciant descriptions of all their bottlings has continued down to the present time, becoming part of both the lore and the cachet of the SMWS. And when you’ve got a wordsmith of the stature of David Mamet confessing that these descriptors gave him a bigger kick than the whisky…well, then you know you have something there.

That first session turned out to be such a success that the format was copied for the initial get together of the Tasting Committee, held in the kitchen of Hills’s house in Edinburgh, and he rather ruefully admits that it was a “motley bunch”. On paper, there was nothing wrong about getting together a set of people who worked with words and knew whisky – the committee included a historian, a professor of Celtic Studies, a professor from LSE among others – but the vocabulary simply wasn’t there (that took time to be developed – another similarity this story shares with rums) and so the quirky characteristic of the Society, that of metaphorical descriptions, was born that evening. That said, in the years that followed, Hills often wrote his own tasting notes, and the insouciant descriptions of all their bottlings has continued down to the present time, becoming part of both the lore and the cachet of the SMWS. And when you’ve got a wordsmith of the stature of David Mamet confessing that these descriptors gave him a bigger kick than the whisky…well, then you know you have something there.

Growth

Unsurprisingly, there were problems. One of the first was alluded to before and was an issue right from the start: distilleries refused to give permission to use their names, fearing trademark infringement and the dilution of their own brand by some fly-by-night cut-rate newbie on the scene who would sell substandard whisky and make them look bad. We see the same thing today with Rum Nation or That Boutique-y Rum Co. and the Compagnie des Indes, who occasionally chuck a “Secret Distillery” moniker on their labels (even though we all know it’s Heisenberg distillate, ha ha). That’s where the concept of numbering came into play – each distillery was assigned a number and as more casks from the same distillery were bought, a period separator provided the detail. So, when one drinks from a bottle numbered 111.3 (assuming it’s available), then that’s a Lagavulin, and their third cask purchase. Inevitably, it was a great marketing tactic as well, and it even became something of an underground mark of erudition to know which was which, and what the numbers meant, and that too became something of a trademark of the Society, redounding to their benefit.

An early meeting of the Tasting Committee (c) SMWS

Another issue was one that afflicts many fast growing enterprises: the inability of management to keep things under control, easier in a smaller concern than the sort of large operation the SMWS was rapidly becoming. Initially, as was natural, everyone knew everyone else and there was a familial, almost clubby atmosphere to the whole thing – the “fun” that was so important to Hills. This became impossible as membership grew. A year after 1.1 was released, the society already had well over 500 members and was bottling from Distillery #10. By the end of 1984 this was up to #16, and 1000 members – and the 10,000th member was signed up a mere four years later, by which time the distilleries number over fifty.

The Board composition changed – Smith ended up resigning after a couple of years as his management style clashed with the other members, to be replaced by Mr. John Lamotte who was no more successful: like his predecessor, he was more into social advancement and a staid, stuffy gentleman’s club style, rather than simply letting things be as a gathering of cheerfully like-minded friends and irreverent aficionados. Hills, seeing that if his own vision was to prevail, finally took over the Chairmanship in the late 1980s, and stayed there until 1995.

Aside from his ideas about the social raison-d’être of the Society, two aspects of his tenure were, for him, non-negotiable. One was that of releasing blended whiskies of their own, which he refused (at the time) to countenance. “There was an element on the Board which just wanted it to make money and provide them with a place in Scotland’s dull whisky establishment,” Hill wrote to me in 2020, with just a twinge of remembered impatience. “I opposed both blended whiskies and vatted malts on the grounds that […] it would have diluted the Society’s message – which in those days was much harder for folk to grasp, since nobody else had done what we were doing.”

Label and bottle designs remained relatively consistent from 1983-2006

Another inviolable rule of the Society which Hills refused to budge on was the advertising, which to him meant – none. He fought many battles with the Board to prevent it…but that did not preclude canny publicity-seeking and brilliant PR, such as the previously noted tasting with journalists. Another coup of this kind was cold-calling Jancis Robinson, a notoriously unimpressible wine writer for the Sunday Times Magazine who finally agreed to meet him, perhaps to just shut him up – he flew to London with five whiskies in a suitcase and she must have really liked what she drank, enough to write a full Sunday feature. In the years that followed, he took author and journalist Paul Levy on a tour of the Speyside distilleries (in a vintage 1937 diesel Lagonda no less) for a spread in the Wall Street Journal; and there was that five-page article in Playboy by David Mamet, among others.

All these efforts raised the profile of the Society and membership not only rocketed up (10k by 1988, remember) but expanded beyond the UK – the French, Japanese and US branches were begun in 1993, followed in the subsequent decades by Canada, Singapore, Australia, Malaysia, Germany and many others – clearly, the formula was a winning one and had an enormously wide geographical spread. I am unclear as to the exact financial and operational relationships such branches have with the mothership, but as Hills remarked, when the Society expanded into other countries, it raised costs.

Sourcing and stocking barrels, bottling and mailing — the entire logistical foodchain — became harder as the whisky world changed around them. Hills stayed on but understood his creation had perhaps outstripped him and wasn’t as interesting as it had once been, and the price demanded by RBS in 1995, for additional funds to keep the organization afloat, was more responsible financial management (meaning, it was implied, “not you”) and a concomitant loss of control…he called it quits and resigned in August of that year. Since then he’s been writing and indulging his own interests, but emerged from a sort of self-imposed obscurity to be part of the SMWS’s 35th Anniversary celebrations in 2018 (he relates an anecdote about the doorman to The Vaults asking him for his membership ID but alas, neglects to say what the reaction was when he said it was Number 001).

Maturity

Even without him, however, the SMWS continued and went from strength to strength. They purchased two more venues in London (2000) and Edinburgh (2004), funded by a share scheme from members; Japanese whiskies were introduced for the first time in 2002 and, without Hills there to block it, the first vatted malt was released the following year. The biggest thing to hit the Society came in 2004: in a move that surprised many, the SMWS was acquired by (or sold to) Glenmorangie. The exact rationale was never stated outright, but it is likely that as it grew perhaps money became a more overriding concern and “fun” conclusively retreated. Glenmorangie allowed a larger selection of whiskies to be released, for one, and with LVMH (the parent company) having rather deeper pockets, some of the financial issues the company evidently continued to have, could be addressed.

What was the cause of these issues that might have precipitated the sale? Having to some extent created – or at least participated in – the modern renaissance of individualized single-cask Scotch whiskies released at full proof, they may have been overtaken by other independents, or distilleries themselves, who didn’t require membership to sell such products and priced them more cheaply. The expansion overseas was another factor, and the logistical difficulties of buying more whiskies to satisfy this demand was surely a third.

What this pointed to was that the Society had become less a membership club than a true independent bottler of international scope. However, this required being nimble and agile in an increasingly competitive marketplace for single cask whiskies if one wanted to retain relevance. It is therefore probably no coincidence that the earlier “standard” green bottles were replaced by the first generation of uniquely-shaped now-iconic tall green ones in 2008, possibly in an effort to lend more pizzazz and originality to their outturns and distinguish them from others made by all the competitors (I can assure you, that succeeded). That same year “Unfiltered” magazine debuted.

New Bottles & Label Design in 2017 (c) SMWS

But by 2015 Glenmorangie had other things on its mind, and their own dedicated whisky brands they wanted to concentrate on, and so the SMWS was sold on again to a group of private investors, thirty in all, some of whom were Society members themselves. The return of members to the management had a number of immediate impacts: reassurance of the rank and file membership that corporate interests were not affecting the brand, and that members themselves were at the helm; a web presence; and, perhaps more importantly, a professional warehousing scheme – the society had become a stockist of some note and instead of simply buying already-aged casks they liked, partnered up with many of the distilleries and were able to buy new make spirit, put them in their own casks, practice rigorous wood management and in all ways expand their potential outturn (as an ancillary note, it would also require a very long term outlook for their maturing stocks). In 2017 they also did another redesign of the bottles – they kept the shape and colour but tinkered with the label, making them, again, a bit more bold and energetic.

Today’s Society

These changes did not come without a price. Older members groused that the “brand” had become less than what it had been and recalled, as most will (and as Hills had) the good old days, that it was no longer fun, no longer that private, small, chummy and collegial “young turks” atmosphere which had so characterized its first years.

An older version of the logo

Also, many new and more sophisticated drinkers of whisky — who, like rummies, are now able to revel in a selection of product that a generation ago was both unthinkable and unavailable — complained about a drop in quality and an increase in prices, forgetting or ignoring how far whisky as a commercial drink had come in that generation. Some even grumbled (or at least remarked on) that the expansion of the Society into other spirits like armagnac, cognac, gin and (heaven forbid!!) rum has been emblematic of its loss of focus.

By 2020, the SMWS was and remains the largest membership club for whiskies – or any spirits, for that matter – in the world. They boast some 28,000 members in 24 countries, release whisky bottlings from over 140 distilleries — and if the speed at which their current outturns sell out is any indication, then no matter how many people resign in protest or bitterly denounce their pricing and marketing strategies, there is no question in my mind that in their own way, they have changed the whisky world irrevocably with their green bottles, and have a legion of purchasers for just about every one of them.

I should know – because while my own belief is that they spent years mucking about with that obscure Scottish tipple before coming to the True Faith of rum (did I say I was a wee bit biased? I might have), I’m a member also, and have not regretted it, if only because it allows me to lay hands on at least some of those fifty or so rums they’ve put out the door, and to write long historical essays like this one, as well as the reviews for the ones I’ve had. And I have to admit, had a lot of fun doing it.

The Rums

Possibly the most significant change to their whisky-only ethos Phillip Hills had so long championed and defended, came just before, and during Glenmorangie’s tenure as the owners, and that was the expansion of the lineup to include not only rum, but cognac, rye, bourbon, gin and armagnac and (in a decision that probably caused him a sleepless night or two) blended malt whisky as of 2017.

The first rums I can find any trace of were released as far back as 2001, and the strange thing is that nobody at the SMWS seems to be able to recall anything about them (other than that they existed). The Society has no online master list of everything they’ve ever issued (“I think your record keeping is much better than the Society’s!” noted Richard Goslan rather wryly, when looking at my own rum list) and photos and anecdotes are all I have.

The first rums – I believe these to be R1.1, R2.1 and R3.1 (but this remains unconfirmed)

Perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised but they were from three Big Guns of rum: Jamaica (Monymusk), Barbados (WIRD) and Guyana (Port Mourant) – I’m going to go out on a limb and suggest they were Releases R1.1 for the Monymusk, R2.1 for the Port Mourant and R3.1 for the WIRD, largely because, even though the bottles don’t look to be numbered, what else could they be? (Note: Troyk890 on Reddit’s /r/rum comment to this post, suggested not, and gave reasons – he felt they may have been special editions). Nothing else preceded them and for many years nothing came after, until a Trinidadian bottling from Providence Estate (which is not Caroni) was released in 2006. Who pioneered the move within the Society, to deal with rum, is a mystery. The source of the casks is unknown. Rum Nation might have found a rum barrel or two mouldering in Scottish distilleries years ago and bought them, but that was an exceptional case, and those days are over – so most likely Main Rum / Scheer or some European broker was involved, which squares with the process most others independents go through.

In any event, the initial issues of rums in 2001 appear to be nothing more than essays in the craft, and excited probably zero interest, much as Velier’s initial offerings from the Age of their Demeraras did. People just weren’t ready for them, and whisky lovers didn’t take rum seriously – it pains me to admit, but they had a point (back then, anyway). Even Serge Valentin, that doyen of the crisply miniscule tasting note, only took note of rum in 2010 himself. So three rums from 2001, a couple from around 2006 and then dead silence until 2012 when eight rums were offered for sale. I have no evidence that diversification and the desire for potential additional revenue streams were behind that decision – that was the year people started to pay rather more attention to rums, you might recall – but to me it seems reasonable, even if the effort died for another four years while Glenmorangie negotiated the sale and the boys in Scotland scratched their sporrans wondering what to do with that annoyingly non-specific but very tasty drink from the Caribbean.

All funning aside, 2016 was the year we can see rums really become a part of the SMWS pantheon. The amount of distilleries got expanded to ten, from all the traditional locales like Guyana, Jamaica, Panama, Nicaragua, Trinidad and Barbados. One wonders why St. Lucia is not part of the lineup, or, for that matter anything from Antigua, Mauritius, Reunion, Japan, Asia or Australia, but we must accept that rum is a vanishingly small part of the SMWS’s knowledge base and they are, remember, primarily a whisky bottler. I’m not saying we should be pulingly grateful, but maybe a shade understanding. They don’t have anyone like us working for them (yet).

A few of The Caner’s Collection of SMWS rums….

Anyway, as of February 2021, there are some 63 rums in the master list (see below for my best effort), with more to come. There is no schedule for the Society, and remember, one has to be a member to buy them when they do come out. That membership fee might have only been £23 a year back in 1983 but it’s more now, plus the cost of the bottle itself – few new entrants into the rumworld are likely to spend that much money for something so erratically released, from a company whose specialty is not even rums.

My own opinion is that there is great potential here for the Society if people ever get bored with its whiskies; and even the rarity of the rums gives them a certain reputation and elicits grumbles of thwarted desire. We need more, not less, and affordably priced, easily available. If the SMWS ever went big time into this corner of the spirits worlds, I think there’s no telling how large that market for its rums would become or where it could end up. Although I have to admit that, like Mr. Hills, I started off by treating them as enormously enjoyable fun drinks, and wrote each of my initial reviews in that vein: if they were to become just like every other indie out there, some of that might conceivably be lost…and that’s even with the insouciant and enjoyable naming of their bottles, and those amusing tasting notes.

Sources

Other Notes

- An article this long will invariably have some errors of omission, or inadvertent (hopefully minimal) factual inaccuracies – those are entirely my responsibility, and where pointed out, I’ll make corrections.

- I have focused most of this bio on the activities of Mr. Hills as a lynchpin, but that should not diminish the contributions of the many others who were involved in the Society — directly, indirectly, peripherally or in-between — over the years: the original Syndicate of founders, the farmer named “Stan,” John Lamotte, Anna Dana, Denise Nielson, Adrian Darke, Richard Gordon, Ritchie Calder and many others.

- In August 2021 I wrote a small piece in SMWS’s “Unfiltered” in house magazine, on why their members should be trying rums. In December of the same year I added a more expanded opinion relating to the Society’s rum releases, to the review of the Jamaican R 1.4

Rum Master List (as of June 2023)

Distillery R1 – Jamaica / Monymusk

Distillery R2 – Guyana / DDL (Various Stills)

- Cask 2 1989-2001 12 YO 66.7% <Unnamed>

- R 2.2 1991-2012 21 YO 71.4% “Too Much of a Good Thing”

- R 2.3 1991-2012 21 YO 69.5% “Visiting a Gothic Art Gallery” (PM)

- R 2.4 1991-2013 22 YO 67.8% “Sweeney Todd in a Victorian Kitchen”

- R 2.5 1991-2013 22 YO 67.8% “Parfait Amour”

- R 2.6 2003-2017 14 YO 51.3% “Banana Flambee”

- R 2.7 2004-2017 13 YO 63.4% “Pleasing and Teasing

- R 2.8 2003-2018 15 YO 58.3% “Out of Our Comfort Zone”

- R 2.9 2008-2019 11 YO 62.0% “Demerara Deliciousness”

- R 2.10 2004-2020 16 YO 59.2% “Explore, Experience, Enjoy!”

- R 2.11 2003-2020 16 YO 59.1% “Goat Farm, Esters & Vinyl Funk”

- R 2.12 2004-2020 15 YO 57.2% “A Precious Treasure Trove”

- R 2.13 2006-2020 14 YO 50.8% “Funky Rum Flavours”

- R 2.14 2003-2020 17 YO 59.4% “Caribbean Crab Cakes”

- R 2.15 2003-2021 17 YO 58.8% “Charismatic Funk”

- R 2.16 2003-2021 17 YO 58.9% “Glue, Glorious Glue!”

- R 2.17 2008-2021 12 YO 61.4% “Swaggering Bravado”

Distillery R3 – Barbados / WIRD

Distillery R4 – Trinidad / Providence Estate

- Cask 4 1990-2006 16 YO 50.9% “Cherry, Chocolate…”

Distillery R5 – Jamaica / Longpond

Distillery R6 – Barbados / Foursquare

Distillery R7 – Jamaica / Hampden Estate

Distillery R8 – Nicaragua / Compañía Licorera de Nicaragua (Flor de Caña)

- R 8.1 1998-2016 18 YO 57.5% “Sneaking a Tot into Woodworking Class”

- R 8.2 1998-2016 18 YO 57.5% “The Hunt Master Before Lunch”

- R 8.3 2014-2016 12 YO 55.0% “Fruit and Nut Case”

- R 8.4 2014-2019 12 YO 57.5% “Campfire in Nicaragua”

- R 8.5 2014-2017 13 YO 68.4% “Sheer Opulence”

- R 8.6 1998-2017 19 YO 68.9% “Nicaragua WD40 Dunderfunk”

- R 8.7 2014-2020 14 YO 67.5% “The Volcanic Spirit”

- R 8.8 1999-2020 21 YO 57.2% “Limbo Dancing In A Kilt”

- R 8.9 2004-2020 15 YO 67.4% “Beef Twerky”

Distillery R9 – Panama / Varelas Hermanos

- R 9.1 2004-2017 13 YO 61.8% “Music for the Rockers of Rum”

- R 9.2 2004-2017 13 YO 62.0% “Paddington Bear’s First Sip”

- R 9.3 2006-2017 11 YO 60.8% “Caramel Custard Doughnut”

- R 9.4 2004-2017 13 YO 62.1% “Chocolate Chili Combo”

- R 9.5 2008-2017 9 YO 64.4% “Stem Ginger and Treacle Tart”

- R 9.6 2004-2019 15 YO 61.6% “Sugar Sweet Sunshine”

- R 9.7 2004-2019 15 YO 62.0% “Patacones with Pikliz”

- R 9.8 2006-2020 14 YO 59.1% “Treacle Thyme”

- R 9.9 2008-2021 13 YO 63.0^ “Challenging Conventional Wisdom”

- R9.10 2006-2022 16 YO 57.9% “Soothing Sensation”

Distillery R10 – Trinidad / Trinidad Distillers (Angostura)

Distillery R11 – Jamaica / Worthy Park

Distillery R12 – Belize / Travellers

- R 12.1 2007-2017 10 YO 66.2% “Morello Cherry Delight”

- R 12.2 2007-2018 11 YO 65.7% “The Stuff That Dreams Are Made of”

Distillery R13 – Trinidad / Caroni

- R 13.1 1998-2018 20 YO 62.3% “Deep dark and Brooding”

- R 13.2 1998-2020 20 YO 62.1% “Ready Made Marmalade”

- R 13.3 1998-2020 20 YO 62.5% “Havana, Madagascar & Tahiti”

- R 13.4 1998-2021 23 YO 61.8% “Bizarre, Bonkers & Brilliant”

Distillery R14 – Guyana / DDL – Port Mourant

- R 14.1 1991-2021 29 YO 58.6% “Papaya The Sailor”

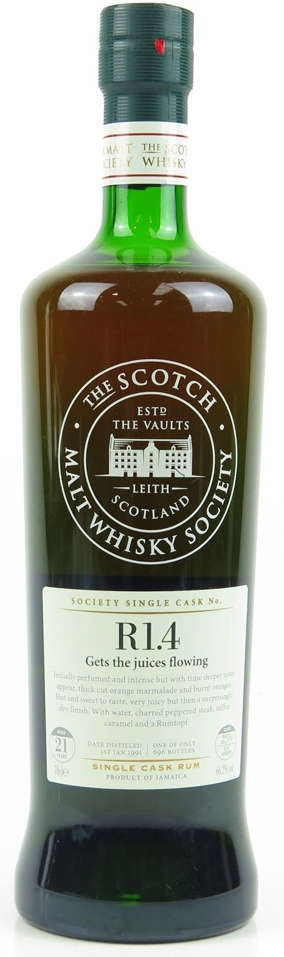

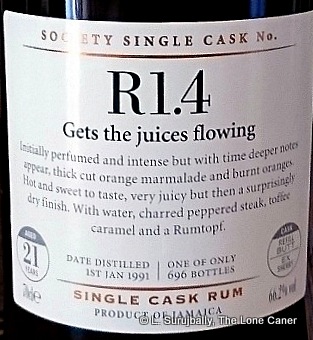

The R1 series (see ‘Other Notes’ below for a quick recap on the numbering schema) of the Society is from Jamaica, Monymusk to be exact and this specific one is from the third issue in 2012, the R1.4, which, in an unconscionable fit of rather reasonable naming, they call “Get the Juices Flowing” … though of course that could describe any Jamaican under the sun. Distilled in 1991, bottled in 2012, the still is unmentioned – however, since Monymusk rum is distilled at Clarendon which has had a columnar still only since 2009, it’s almost certainly a pot still rum. A peculiarity is the outturn: 696 bottles from a “single cask”, which the label helpfully tells us was a sherry butt (likely 500 liters or perhaps more), and as we know from experience, the Society does not muck around with proof but releases it as is from the cask – 66.2% here.

The R1 series (see ‘Other Notes’ below for a quick recap on the numbering schema) of the Society is from Jamaica, Monymusk to be exact and this specific one is from the third issue in 2012, the R1.4, which, in an unconscionable fit of rather reasonable naming, they call “Get the Juices Flowing” … though of course that could describe any Jamaican under the sun. Distilled in 1991, bottled in 2012, the still is unmentioned – however, since Monymusk rum is distilled at Clarendon which has had a columnar still only since 2009, it’s almost certainly a pot still rum. A peculiarity is the outturn: 696 bottles from a “single cask”, which the label helpfully tells us was a sherry butt (likely 500 liters or perhaps more), and as we know from experience, the Society does not muck around with proof but releases it as is from the cask – 66.2% here.  This creates some interesting commercial dynamics. With thousands of members around the globe and only a few hundred bottles per release (single barrel, remember), it’s inevitable that most people wanting, say, one of the 275 bottles of release 66.177, will be SOL. The society has responded to this inevitable problem by issuing many more expressions in a given period than ever before, from all over the flavour map, and allocating supplies all over the world. They have begun doing blends. Prices are not subject to escalation (except on secondary markets). And of course they have dabbled their toes into other spirits categories as well – gin, bourbon, Armagnac, rum, and so on.

This creates some interesting commercial dynamics. With thousands of members around the globe and only a few hundred bottles per release (single barrel, remember), it’s inevitable that most people wanting, say, one of the 275 bottles of release 66.177, will be SOL. The society has responded to this inevitable problem by issuing many more expressions in a given period than ever before, from all over the flavour map, and allocating supplies all over the world. They have begun doing blends. Prices are not subject to escalation (except on secondary markets). And of course they have dabbled their toes into other spirits categories as well – gin, bourbon, Armagnac, rum, and so on.