“Hither came Conan, the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandalled feet.”

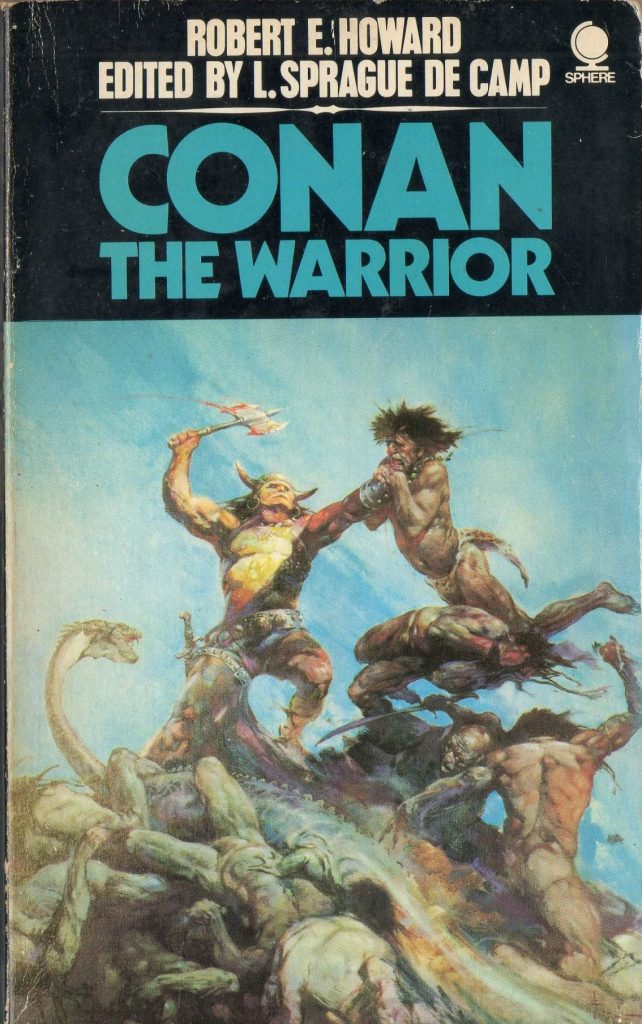

So goes the introduction to perhaps the iconic hero of all Sword and Sorcery tales, themselves a subset – or bastard cousin – of the heroic fantasy genre. Is there a man alive who has not at some point heard of Conan the Cimmerian? Or seen the vivid paintings of Frank Frazetta and been transported into the mystical and legendary kingdoms of Hyboria? In penning these tales of mythical times long past, Robert E. Howard created one of the great characters of modern American fiction, and one I have returned to time and time again when the weighty tomes of non-fiction or the effort to come to grips with some intellectually subtle point of a Booker Prize contender simply becomes too much for me. Conan hearkens back to the dime novels and penny dreadfuls of the disreputable past, reeks of cheap print on cheaper paper, and redolent of a black and white time when unsentimental heroes talked tough and cracked wise. Sure Burroughs created Tarzan earlier, L’Amour the Sacketts later, and Dashiell Hammett , Raymond Chandler and John M Cain also wrote tough tales of pulp: but among them all coils Howard.

Robert E. Howard, who committed suicide at the age of thirty, wrote some eighteen stories of varying lengths about Conan during his lifetime (along with a huge volume of general pulp magazine fiction covering all fields and genres), most of which were published in Weird Tales; eight others were pieced together from his complete and incomplete papers after his death, and published posthumously. L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter adapted Howard’s notes and outlines to add another four complete stories and a few pastiches, while other authors as varied as Robert Jordan and Poul Anderson have added another fifty or so to the body of work: but the core of it all remains the eighteen Howard himself wrote. These are the backbone of the ten paperback volumes that document most of Conan’s life, from the first “Conan” where he is eighteen or so, to “Conan the Avenger,” the tenth, where he is in his mid forties, King of Aquilonia, and has a wife and son.

Howard remarked in one his letters that he preferred to write about straightforward heroes with muscles, not brains. His reasoning had a sort of charming simplicity to it: in a jam, nobody expected them to think their way out of things – they just hacked, slashed, brawled or shot their way out of trouble (and all his other heroes – Bran Mak Morn, Solomon Kane, King Kull, Turlogh O’Brien – followed this general trend). In the highly mythological world of Hyboria, all men were cast in a sort of stark relief, with simple, strong characteristics, and all women were curvaceous, beautiful and not at all meek. The impact of Howard’s virile, magic-infested creation was like a blast of colour in a black and white world, and let’s face it: Tolkien might have written about noble sylvan elves in gentle northern climes, but it’s a subtle wine compared to the savage red bouquet of Hyboria’s realism. This kind of writing marries the colour and dash of historical romance fiction with the atavistic supernatural thrills of the weird, occult or ghost story. In short, it’s escapism at its best.

Howard remarked in one his letters that he preferred to write about straightforward heroes with muscles, not brains. His reasoning had a sort of charming simplicity to it: in a jam, nobody expected them to think their way out of things – they just hacked, slashed, brawled or shot their way out of trouble (and all his other heroes – Bran Mak Morn, Solomon Kane, King Kull, Turlogh O’Brien – followed this general trend). In the highly mythological world of Hyboria, all men were cast in a sort of stark relief, with simple, strong characteristics, and all women were curvaceous, beautiful and not at all meek. The impact of Howard’s virile, magic-infested creation was like a blast of colour in a black and white world, and let’s face it: Tolkien might have written about noble sylvan elves in gentle northern climes, but it’s a subtle wine compared to the savage red bouquet of Hyboria’s realism. This kind of writing marries the colour and dash of historical romance fiction with the atavistic supernatural thrills of the weird, occult or ghost story. In short, it’s escapism at its best.

“Conan the Warrior” the seventh book in the cycle, takes place when Conan is in his mid- to late-thirties, and the three novellas in it are called “Red Nails”, “Jewels of Gwahlur” and “Beyond the Black River”. At this stage in his career, Conan had already been a freebooter, a pirate, a mercenary, gained the name “Amra” and seen much of the world. Howard himself wrote these three, and for my money, they are among the best he ever did: “The Frost Giant’s Daughter” and “Queen of the Black Coast” are also in that exalted company, but in separate books, and so I have selected this trio as an introduction to Howard and his Cimmerian.

“Red Nails” stands as the most evocative of the three, with Conan and Valeria of the Red Brotherhood escaping a monster in a forest to come upon a massive, all-enclosed stone city inhabited by the remnants of two warring peoples, who hammer one red nail into a massive ebony column for each enemy they kill. The arrival of Conan and Valeria tips the balance decisively towards one of the two dying tribes, yet friendship, betrayal, lust, sorcery, action and dark magic all have their turn on this tautly written tale.

After parting company with Valeria (the stories are roughly chronological), Conan heads to the jungle to raid a legendary treasure city of Gwahlur (hidden inside the caldera of an extinct volcano), but finds more than he bargained for when the priests who live there are slaughtered by strange beasts and Conan barely makes it out alive.

Lastly, Conan heads to the pictish frontier along the Black River, just as the tribes unite and boil over the border to massacre all the Aquilonian settlers on the Bossonian marches, under their mad sorcerer Zogar Sag. If “Red Nails” had a sense of time and place in the darkened stone-covered city that was unique and vibrant, “Beyond the Black River” is the best short novel of forest war and magic I’ve ever read, with strong pacing and fast action that never loses or confuses its way.

It’s a credit to the strength of Howard’s writing that after a bit one can tell which is his work and which is done by others. Nothing Sprague de Camp wrote in his reworking of later stories comes even close to Howard. Consider this passage from “Red Nails” – Olmec was as tall as Conan, and heavier; but there was something repellent about the Tlazitlan, something abysmal and monstrous that contrasted unfavourably with the clean-cut compact hardness of the Cimmerian….if Conan was a figure out of the dawn of time, Olmec was a shambling somber shape out of the darkness of time’s pre-dawn. Or this one: In the cold, loveless and altogether hideous life of the Tecuhltli, his admiration and affection for the invaders from the outer world formed a warm, human oasis that constituted a tie which connected him with a more natural humanity totally lacking in his fellows, whose only emotions were hate, lust and the urge to sadistic cruelty. This is pulp fiction at its best: closely worded descriptions of appearance and motivation, stark identity and basic emotions. And yet I defy anyone to read any of these stories and not admit how vibrant and rich in imagery they are. How strong and direct when compared against the more subtle offerings to which we are accustomed.

And this is not all. If they had been merely thrilling reads – which they are – I wouldn’t have bothered putting the work up for consideration. But Howard’s work presaged much else in modern literature and drew from a well-established wellspring of past tribal lore. Conan is the archetype of the Lone Hero – almost a Nietzschean superman – scattered throughout mankind’s oldest legends, and can be found in much of present day fiction: in Conan we see shades of Hondo and Jason Bourne, of The Road Warrior, the Hardened Street Cop, or the Solitary Soldier on the field of battle. He’s Audie Murphy with a sword.

And this is not all. If they had been merely thrilling reads – which they are – I wouldn’t have bothered putting the work up for consideration. But Howard’s work presaged much else in modern literature and drew from a well-established wellspring of past tribal lore. Conan is the archetype of the Lone Hero – almost a Nietzschean superman – scattered throughout mankind’s oldest legends, and can be found in much of present day fiction: in Conan we see shades of Hondo and Jason Bourne, of The Road Warrior, the Hardened Street Cop, or the Solitary Soldier on the field of battle. He’s Audie Murphy with a sword.

In “Jewels” one can sense Michael Crichton’s “Congo;” “Black River” is really a rewritten western of the kind John Ford would make popular in his films and Louis L’Amour in his novels. And the darkness of Howard’s magic and sorcery has echoes of Lovecraftian horror: indeed, the two were correspondents, and some argue that the darkly beautiful fiction of the Cthulu mythos has its origins in Conan (though the reverse has also been posited and that Conan’s Hyboria is a subset of Lovecraft’s more insanely imagined worlds). And from there, a straight line can be drawn into “Xena”, Dungeons and Dragons, Warcraft, “Wizard’s First Rule,” and Stephen King.

Lastly, attention should be drawn to Frank Frazetta, whose dark and savagely iconic paintings of the sword and sorcery genre practically redefined fantasy art as we know it (The Legend of Zelda computer game explicitly named Frazetta’s Conan work as an inspiration) and took residence in our imaginations of such places: no elves and dwarves and green dales here, but shambling horrors, beautiful women and ferocious large-thewed men, in bloody battle with sharp glittering weapons under dark stone towers of crumbling and ruined civilizations.

How one crazy young Texan writing for a pulp magazine during the Depression could so completely influence an entire literary genre and have an impact decades hence in fields not imagined in his day is not something about which I can hazard a guess. All I know is that the cables stretching from his stories to these times are there, and in this one book of three superlative tales one can still find them, tautly vibrating and calling us in with their magic.