A kokuto shochu, one of the oldest spirits made in Japan, derives from unrefined sugar (kokuto) and in that sense it straddles an uneasy and somewhat undefined territory between agricole-style and molasses-based rums. Nosing the clear spirit demonstrates that: it opens with a lovely crisp agricole type brine and sweet alcohol, channelling sweet soda pop – Fanta, 7-Up, a bit of funk, a bit of citrus; and then adds a pot still kind of funkiness to the mix, like the aroma of fresh glue on a newly installed carpet, paint, varnish, and a lot — a lot — of fresh, light, tart, fruity notes. Guavas, Thai mangoes, strawberries, light pineapples, mixed fruit ice cream, yoghurt. Yamada Distillery makes two shochus and this is the one they call “Intense” – based solely on how it smells, I believe them.

A kokuto shochu, one of the oldest spirits made in Japan, derives from unrefined sugar (kokuto) and in that sense it straddles an uneasy and somewhat undefined territory between agricole-style and molasses-based rums. Nosing the clear spirit demonstrates that: it opens with a lovely crisp agricole type brine and sweet alcohol, channelling sweet soda pop – Fanta, 7-Up, a bit of funk, a bit of citrus; and then adds a pot still kind of funkiness to the mix, like the aroma of fresh glue on a newly installed carpet, paint, varnish, and a lot — a lot — of fresh, light, tart, fruity notes. Guavas, Thai mangoes, strawberries, light pineapples, mixed fruit ice cream, yoghurt. Yamada Distillery makes two shochus and this is the one they call “Intense” – based solely on how it smells, I believe them.

The taste is, in a word, light. There’s a reason for this which I’ll get to in a moment, but the bottom line is that this is a spirit to drink neat and drink easy because the flavours are so delicate that mixing it would shred any profile that a neat pour would lead you expect. It’s faint, it’s sweet, it’s extremely light, and what I think of when trying it is the soft florals of cherry blossoms, hibiscus; herbs like thyme and mint, mixed up with light yellow and white fruits, cherries, grapes. It’s enormously drinkable, and beats the hell out of any indifferently made 40% blanco in recent memory…and if the finish is practically nonexistent, well, at least there are some good memories from the preceding stages of the experience.

There’s a good reason for its lightness, its sippability — and that’s because it’s a mere 30% ABV. By rum standards, where the absolute lower limit is 37.5% before heading into liqueur country, that disqualifies it from being considered a rum at all: even if we were to accept the dual fermentation cycle and its unrefined sugar base, to the rum-drinking world that strength is laughable. I mean, really?….30%??! One could inhale that in a jiffy, down a bottle without blinking, and then wash it down with a Malibu.

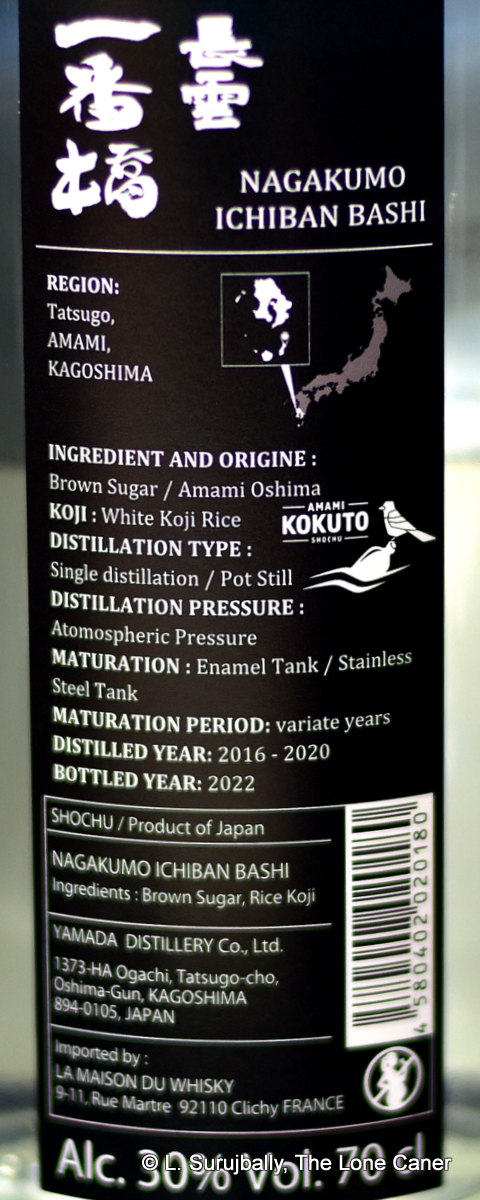

Consider the provenance and specs, and park the ABV for a moment. It comes from the Amami islands in southern Japan (between Kagoshima and Okinawa), made by a tiny, family run distillery on Oshima Island 1that has existed for three generations, since 1957 — that’s considered medium old by the standards of the islands, where firms can either be founded last year, or a century ago. Perhaps they are more traditional than most, because there are no on-site tastings, no distillery sales, and no website – it seems to be a rare concession for them to even permit tours (maximum of five people), and have as much as a twitter and instagram account.

Consider the provenance and specs, and park the ABV for a moment. It comes from the Amami islands in southern Japan (between Kagoshima and Okinawa), made by a tiny, family run distillery on Oshima Island 1that has existed for three generations, since 1957 — that’s considered medium old by the standards of the islands, where firms can either be founded last year, or a century ago. Perhaps they are more traditional than most, because there are no on-site tastings, no distillery sales, and no website – it seems to be a rare concession for them to even permit tours (maximum of five people), and have as much as a twitter and instagram account.

But that aside, the Nagakumo Ichiban Bashi is practically handmade to demonstrate terroire. The brown sugar is local, from Oshima, not Okinawa, and that island. They distil in a single pass, in a pot still. The resultant is rested, not aged (at least, not in the way we would understand it), in enamelled steel tanks for several years in a small solera system. And the resultant is really quite fascinating: similar enough to a rum not to lose me, and different enough to pique my interest. Even at its wobbly proof point, the whole thing has a character completely lacking in those anonymous, androgynous, filtered whites that sell everywhere.

Shochus generally, and kokuto shochus in particular, must, I think, be drunk and appreciated on their own level, with an understanding of their individual social and production culture. It is useful to come at them from a rum perspective, but perhaps we should give them space to be themselves, since to expect them the adhere to strength and profile of actual rums is to misunderstand the spirit.

Admittedly therefore, the low strength makes the shochu rate a fail when rated by western palates accustomed to and preferring sterner stuff. My personal feeling is that it works on its own level, and that nose, that lovely, robust, floral, aromatic nose…I mean, just smell that thing a few more times — it makes up for all its faintness of the palate. Perhaps the redeeming feature of the shochu is that you can channel your inner salaryman after work, sip and drink this thing multiple times, still not get a debilitating buzz on, and still find some notes to enjoy. There aren’t too many cask strength rums that allow you to do that.

(#945)(78/100) ⭐⭐⭐

Other notes

- The LMDW entry for this shochu says it is made partly from Thai rice to which muscovado sugar is then added. This is wrong. The koji mould which is used for primary fermentation is developed on Thai rice. But rice is not used as a source of the wash.

- Shochu is an entire spirit to itself, and kokuto shochu is a subset of that. For the curious there is a complete backgrounder available, with all sources noted.

- The name on the label, 3S, is a Japanese concern that deals primarily in shochu (the three “S” moniker stands for “Super Shochu Spirits”) where they act as an independent bottler. They are a subsidiary of G-Bridge company, which is a more general trading house established in 2006.

- I feel that the sugar cane derivative base of kokuto makes it part of the rum family. An outlier, true, but one which shares DNA with another unrefined-brown-sugar-based spirit such as we looked at with Habitation Velier’s jaggery-based Amrut, and the panela distillates of Mexico. If it doesn’t fall within our definitions then we should perhaps look more carefully at what those definitions are and why they exist. In any case, there are shochus out there that do in fact got to 40% and above. It suggests we pay attention to such variations — because we could, in all innocence, be missing out on some really cool juice.