Haiti is unique as a nation because it is where the only successful slave revolt in the world took place, at the turn of the 18th century. Sadly, it is now the poorest country in the western hemisphere, and successive dictatorships, foreign interference and natural disasters have left the place in shambles.

That any businesses manage to survive in such an environment is a testament to their resilience, their determination, their ingenuity….and the quality of what they put out the door. The country has become the leading world producer of vetiver (a root plant used to make essential oils and fragrances), exports agricultural products and is a tourist destination, yet perhaps it is for rum that its exports are best known, and none more so than those of Barbancourt, formed in 1862 and still run by the descendants of the founder.

Until the mid 20th century, Barbancourt was something of a cottage industry, selling primarily to the local market. In 1949 they relocated the sugar cane fields of the Domaine Barbancourt in the plaine du Cul-de-Sac region in the south east, and by 1952 ramped up production, increased exports and transformed the brand into a major producer of quality rum, a distinction it has held ever since.

The rhum, based on sugar cane juice not molasses, used to be double-distilled, using pot stills in a process similar to that used to produce cognac (Dupré Barbancourt came from the cognac-producing region of Charente which was undoubtedly his inspiration); however, nowadays they use a more efficient (if less character-driven) three-column continuous distillation system, where the first column strips the solid matter from the wash and the second and third columns serve to concentrate the resultant spirit…so what is coming to the market now is not what once was made by the company.

Haiti has no shortage of other rhum producing companies – but smaller outfits like Moscoso Distillers or LaRue Distillery are much less well-known and export relatively little, (and back-country clairins are in a different class altogether)…and this makes Barbancourt the de facto rum standard bearer for the half island, and one of the reasons I chose it for this series. This is not to dismiss the efforts of all the others, or the the artisanal quality of the clairins that Velier has brought to world attention since 2014 — just to note that they all, to some extent, live in the shadow of Barbancourt; which in turn, somewhat like Mount Gay, seems in danger of being forgotten as a poster boy for Haiti, now that the pure artisanal rum movement gathers a head of steam.

The current label of the 8YO

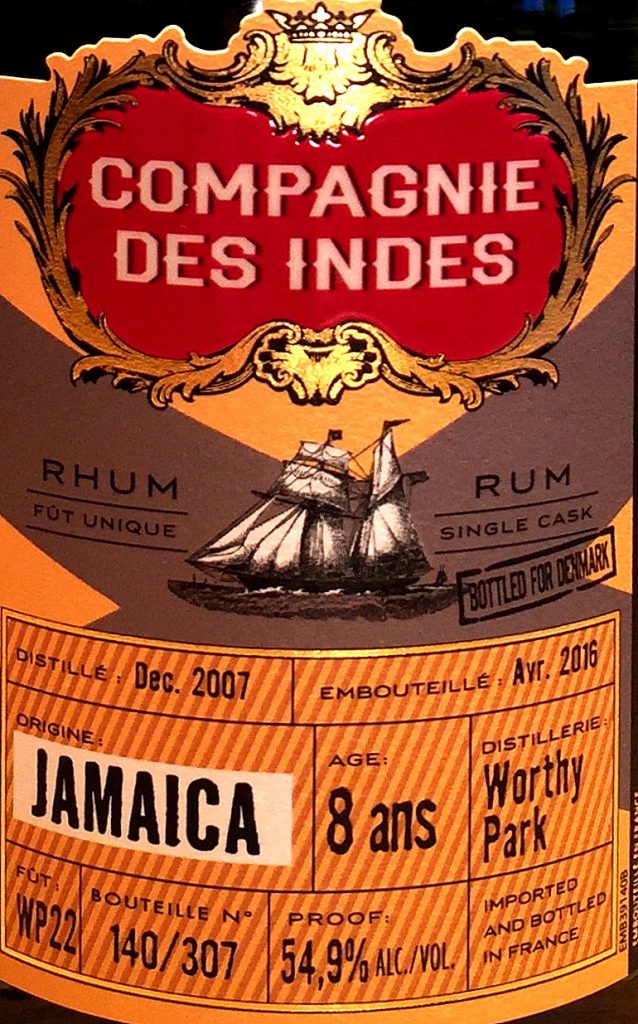

Barbancourt’s rhums are not issued at full proof: they prefer a relatively tame 40-43%, and every possible price point and strength is not catered to. The company has a relatively small stable of products: the Blanc, the 3-star 4 Year Old, the 5-star 8 Year Old and the flagship 15 year old (Veronelli’s masterful 25 year old is a Barbancourt rhum, but not issued by them). Though if one wanted to get some, then independent bottlers like Berry Bros., Bristol Spirits, Duncan Taylor, Cadenhead, Samaroli, Plantation and Compagnie des Indes (among others) do produce stronger and more exacting limited offerings for the enthusiasts.

Yet even with those few rhums they make, whatever the competition, and whether one calls it a true agricole or not, the rhums coming from Barbancourt remain high on the quality ladder and no rumshelf could possibly be called complete without at least one of them. After trying and retrying all three major releases, my own conclusion was that at the intersection of quality and price, the one that most successfully charts a middle course between the older and the younger expressions is the 5-star 8 year old (I looked at it last way back in 2010, as well as one earlier version from back in the 1970s) which remains one of the workhorses of the company and the island, an excellent mid-level rum that almost defines Barbancourt.

It does display, however, somewhat of a schizophrenic profile. Take the nose, for example – it almost seems like a cross between a molasses based rum and an agricole. While it certainly possesses the light, herbal aroma of a cane-juice distillate, it also smells of a light kind of brown sugar and molasses mixed up with some bananas and vanilla (it was aged in French oak on Haiti, which may account for the latter). There’s also a sly briny background, combined with a pleasant hints of nougat and well polished leather, plus the subdued acidity of green apples, grapes and cumin. Not all that intense at 43%, but excellent as an all-rounder for sure.

What the nose promises, the palate delivers, and yet that peculiar dichotomy continues. It’s soft given the strength, initially tasting of caramel, toblerone, almonds and vague molasses and vanilla (again). Brine and olives. Spices – cumin, cinnamon, plus raisins, a certain delicate grassiness and maybe a plum or two (fruitiness is there, just understated). Nope, it doesn’t feel like a completely cane juice distillate, or, at best, if feels like an amalgam leading neither one way or the other, and the close sums all that up. It’s medium long, with salt caramel ice cream, vanilla, a bit of raisins and plums, a fine line of citrus, a little cinnamon dusting, and a last reminder of oaky bitterness in a relatively good, dry finish.

What makes the Barbancourt 8 YO so interesting — even unique — is the way the makers played with the conventions and steered a center line that draws in lovers of other regions while not entirely abandoning the French island antecedents. It reminds me more of a Guadeloupe rhum than an out-and-out agricole from Martinique, with perhaps a pinch of Bajan thrown in. However, it’s in no way heavy enough to invite direct comparisons to any Demerara or Jamaican product.

So, does it fail as a Key Rum because of its indeterminate nature, or because it lacks the fierce pungency of a clairin, the full grassy nature of a true agricole?

Not at all, and not to me. It’s a completely solid rhum with its own clear profile, that succeeds at being drinkable and enjoyable on all levels, without being visibly exceptional in any specific way and sold at a price point that makes it affordable to the greater rum public out there. Many reviewers and most drinkers have come across it at least once in their journey (much more so than those who have tried clairins) and few have anything bad to say about it. It’s been made for decades, is well known and well regarded — not just because it’s from Haiti, but because it also has a great price to value ratio. There’s a lot of talk about “gateway” rums, cheaper and sometimes-adulterated rums that are good enough to enjoy and savour, that lead to more and better down the road. It’s usually applied to the Zacapas, Zayas, Diplos and younger rums of this world, but if you ever want to get more serious about aged agricoles, then the Barbancourt 8 YO may actually be one of those that actually deserves the title, and remains, even after all these years, a damned fine place to start your investigations.

(#592)(84/100)

Other Notes

In a curious coincidence, a post on reddit that did a brief review of this rhum went up just a few days before this was published. There are some good links contained within the commentary.

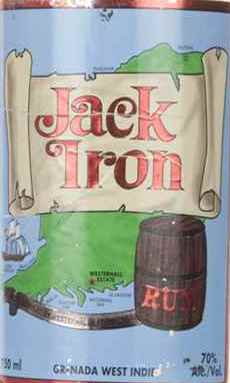

The Jack Iron rum from Westerhall is a booming overproof issued both in a slightly aged and a white version, and both are a whopping 70% ABV. While you can get it abroad — this bottle was tried in Italy, for example — my take is that it’s primarily a rum for local consumption (though which island can lay claim to it is a matter of idle conjecture), issued to paralyze brave-but-foolhardy tourists who want to show off their Chewbacca chests by drinking it neat, or to comfort the locals who don’t have time to waste getting hammered and just want to do it quick time. Add to that the West Indian slang for manly parts occasionally being iron and you can sense a sort of cheerful and salty islander sense of humour at work (see “other notes” below for an alternative backstory).

The Jack Iron rum from Westerhall is a booming overproof issued both in a slightly aged and a white version, and both are a whopping 70% ABV. While you can get it abroad — this bottle was tried in Italy, for example — my take is that it’s primarily a rum for local consumption (though which island can lay claim to it is a matter of idle conjecture), issued to paralyze brave-but-foolhardy tourists who want to show off their Chewbacca chests by drinking it neat, or to comfort the locals who don’t have time to waste getting hammered and just want to do it quick time. Add to that the West Indian slang for manly parts occasionally being iron and you can sense a sort of cheerful and salty islander sense of humour at work (see “other notes” below for an alternative backstory).

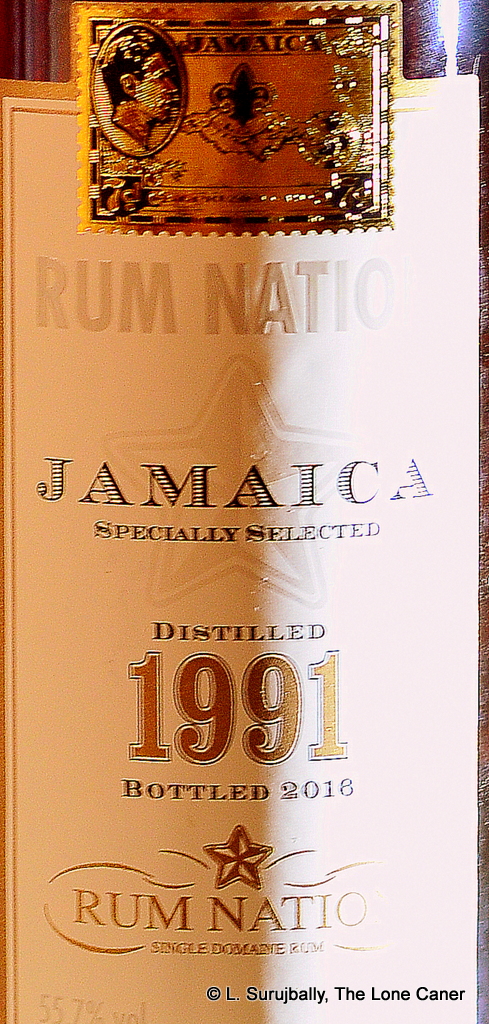

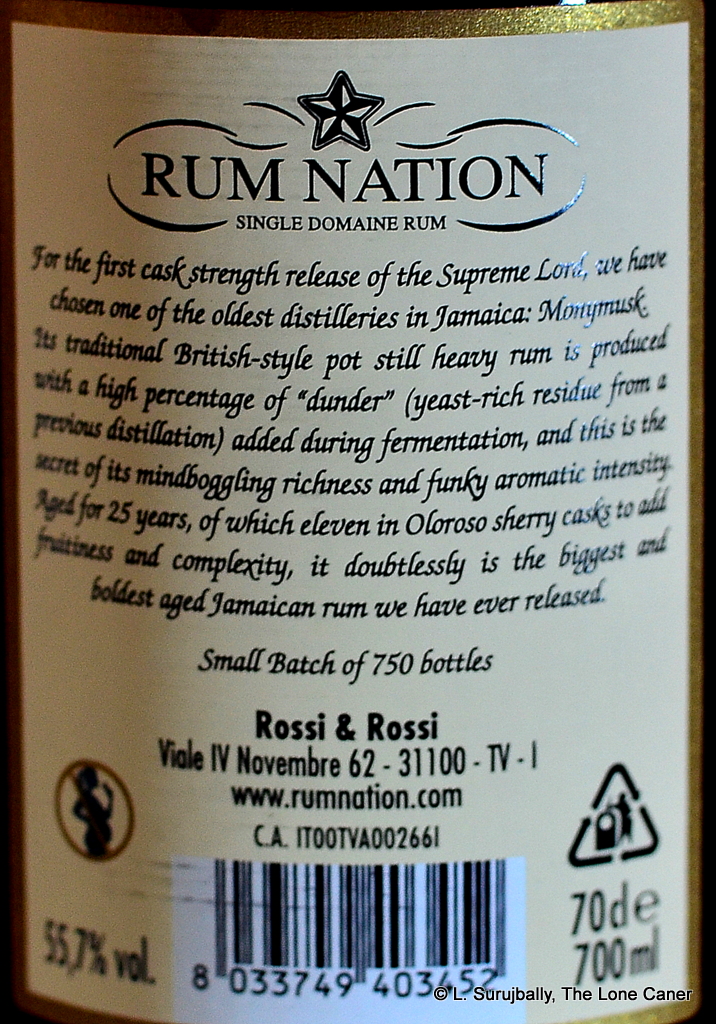

And for anyone who enjoys sipping rich Jamaicans that don’t stray too far into insanity (the

And for anyone who enjoys sipping rich Jamaicans that don’t stray too far into insanity (the  The rum continues along the path set by all the seven Supreme Lords that came before it, and since I’ve not tried them all, I can’t say whether others are better, or if this one eclipses the lot. What I do know is that they are among the best series of Jamaican rums released by any independent, among the oldest, and a key component of my own evolving rum education.

The rum continues along the path set by all the seven Supreme Lords that came before it, and since I’ve not tried them all, I can’t say whether others are better, or if this one eclipses the lot. What I do know is that they are among the best series of Jamaican rums released by any independent, among the oldest, and a key component of my own evolving rum education.

This brings us to the

This brings us to the

Because for the unprepared (as I was), the nose of this rum is edging right up against revolting. It’s raw, rotting meat mixed with wet fruity garbage distilled into your rum glass without any attempt at dialling it down (except perhaps to 40% which is a small mercy). It’s like a lizard that died alone and unnoticed under your workplace desk and stayed there, was then soaked in diesel, drizzled with molten rubber and tar, set afire and then pelted with gray tomatoes. That thread of rot permeates every aspect of the nose – the brine and olives and acetone/rubber smell, the maggi cubes, the hot vegetable soup and lemongrass…everything.

Because for the unprepared (as I was), the nose of this rum is edging right up against revolting. It’s raw, rotting meat mixed with wet fruity garbage distilled into your rum glass without any attempt at dialling it down (except perhaps to 40% which is a small mercy). It’s like a lizard that died alone and unnoticed under your workplace desk and stayed there, was then soaked in diesel, drizzled with molten rubber and tar, set afire and then pelted with gray tomatoes. That thread of rot permeates every aspect of the nose – the brine and olives and acetone/rubber smell, the maggi cubes, the hot vegetable soup and lemongrass…everything. Just as we don’t see Americans making too many full proof rums, it’s also hard to see them making true agricoles, especially since the term is so tightly bound up with the spirits of the French islands.

Just as we don’t see Americans making too many full proof rums, it’s also hard to see them making true agricoles, especially since the term is so tightly bound up with the spirits of the French islands.

We don’t much associate the USA with cask strength rums, though of course they do exist, and the country has a long history with the spirit. These days, even allowing for a swelling wave of rum appreciation here and there, the US rum market seems to be primarily made up of low-end mass-market hooch from massive conglomerates at one end, and micro-distilleries of wildly varying output quality at the other. It’s the micros which interest me, because the US doesn’t do “independent bottlers” as such – they do this, and that makes things interesting, since one never knows what new and amazing juice may be lurking just around the corner, made with whatever bathtub-and-shower-nozzle-held-together-with-duct-tape distillery apparatus they’ve slapped together.

We don’t much associate the USA with cask strength rums, though of course they do exist, and the country has a long history with the spirit. These days, even allowing for a swelling wave of rum appreciation here and there, the US rum market seems to be primarily made up of low-end mass-market hooch from massive conglomerates at one end, and micro-distilleries of wildly varying output quality at the other. It’s the micros which interest me, because the US doesn’t do “independent bottlers” as such – they do this, and that makes things interesting, since one never knows what new and amazing juice may be lurking just around the corner, made with whatever bathtub-and-shower-nozzle-held-together-with-duct-tape distillery apparatus they’ve slapped together.

Oh yes…though it is different – some might even sniff and say “Well, it isn’t Foursquare,” and walk away, leaving more for me to acquire, but never mind. The thing is, it carved out its own olfactory niche, distinct from both its older brother and better known juice from St. Phillip. It was warm, almost but not quite spicy, and opened with aromas of biscuits, crackers, hot buns fresh from the oven, sawdust, caramel and vanilla, before exploding into a cornucopia of cherries, ripe peaches and delicate flowers, and even some sweet bubble gum. In no way was it either too spicy or too gentle, but navigated its way nicely between both.

Oh yes…though it is different – some might even sniff and say “Well, it isn’t Foursquare,” and walk away, leaving more for me to acquire, but never mind. The thing is, it carved out its own olfactory niche, distinct from both its older brother and better known juice from St. Phillip. It was warm, almost but not quite spicy, and opened with aromas of biscuits, crackers, hot buns fresh from the oven, sawdust, caramel and vanilla, before exploding into a cornucopia of cherries, ripe peaches and delicate flowers, and even some sweet bubble gum. In no way was it either too spicy or too gentle, but navigated its way nicely between both.

To be honest, the initial nose reminds me rather more of a Guyanese Uitvlugt, which, given the still of origin, may not be too far out to lunch. Still, consider the aromas: they were powerful yet light and very clear – caramel and pancake syrup mixed with brine, vegetable soup, and bags of fruits like raspberries, strawberries, red currants. Wrapped up within all that was vanilla, cinnamon, cloves, cumin, and light citrus peel. Honestly, the assembly was so good that it took effort to remember it was bottled at a hefty 66% (and wasn’t from Uitvlugt).

To be honest, the initial nose reminds me rather more of a Guyanese Uitvlugt, which, given the still of origin, may not be too far out to lunch. Still, consider the aromas: they were powerful yet light and very clear – caramel and pancake syrup mixed with brine, vegetable soup, and bags of fruits like raspberries, strawberries, red currants. Wrapped up within all that was vanilla, cinnamon, cloves, cumin, and light citrus peel. Honestly, the assembly was so good that it took effort to remember it was bottled at a hefty 66% (and wasn’t from Uitvlugt).

Rumaniacs Review #087 | 0574

Rumaniacs Review #087 | 0574 Now here’s an interesting standard-proofed gold rum I knew too little about from a country known mostly for the spectacular temples of Angor Wat and the 1970s genocide. But how many of us are aware that Cambodia was once a part of the Khmer Empire, one of the largest in South East Asia, covering much of the modern-day territories of Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Viet Nam, or that it was once a protectorate of France, or that it is known in the east as Kampuchea?

Now here’s an interesting standard-proofed gold rum I knew too little about from a country known mostly for the spectacular temples of Angor Wat and the 1970s genocide. But how many of us are aware that Cambodia was once a part of the Khmer Empire, one of the largest in South East Asia, covering much of the modern-day territories of Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Viet Nam, or that it was once a protectorate of France, or that it is known in the east as Kampuchea?