Part 1 – Influences & Developments to 2005

Introduction

Take a look at the rum world in 2018, and several aspects jump out immediately. The top-end rums getting most of the press and user approbation are almost all rums issued at cask strength; many, if not most, are made by an ever-increasing stable of independent bottlers, with Foursquare being one of the few primary producers making such strong rums as part of their core lineup, and others hastening to catch up. Rums are often being made “pure,” which is to say without additives, labels are much more informative than ever before, and unaged whites are becoming more and more popular (and appreciated). The major large-company rum brands of ten years ago – many of which were and are aged blends – remain enormously popular but have almost all been relegated to second-tier status in the eyes of knowledgeable aficionados. And the dissemination of information regarding rums – whether via news stories, magazine click-bait, blogs, review sites, Reddit forums or Facebook rum clubs – has enabled the trend in this direction exponentially.

When one considers the state of the rum world prior to 2005, this ninety-degree turn in the drinking habits of the tippling class seems well nigh unprecedented. It is my considered opinion that the Demerara (and to a lesser extent the Caroni) rums issued by Velier in the years 2005 to 2014 were instrumental in altering the rum landscape in a way few rums before ever had, or ever will again. To this day, many consider them among the best rums from Guyana ever issued, and that includes the independents (of which Velier was surely one in spite of being primarily an importer). Many of the concepts we take for granted when choosing top-shelf rums from Guyana – indeed, from anywhere – were encapsulated and brought to a wider audience by the Demerara series. We live in the world they helped make, and it is our loss that they ceased being issued almost before we even properly acknowledged their existence.

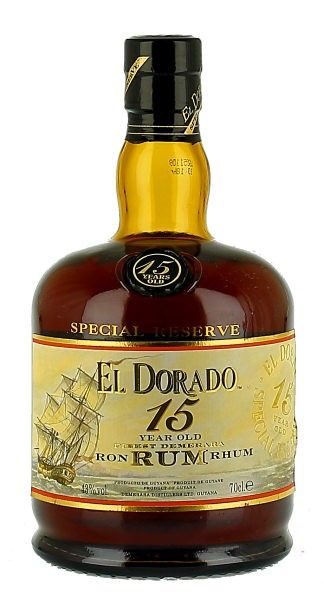

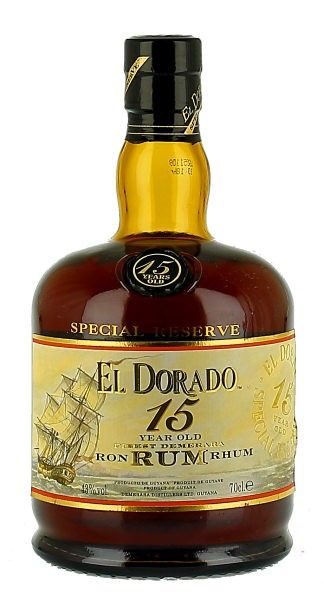

In this first portion of a rather long three-part essay I’m going to look at the trends, influences and developments that I believe laid the foundations for what is unofficially called the Age of Velier’s Demeraras. I argue that these were the release of the El Dorado 15 year old in 1992, the rise of the internet, three books, a website, proliferating independent bottlers in Europe — all of which led to a more informed and rum-educated drinking cadre, some of whom went on to form the first websites devoted to rums and reviews. Also, oh yes….there was a small Italian importer….

As it was then…

The rum world in the 1980s was a rather staid one, moving along very much as it had for years before. Major rum companies from around the Caribbean were issuing more or less the same rums they had been for decades – then as now, 40% ABV was practically a standard, age almost uniformly under ten years (if mentioned at all), and the market was full of familiar brands, similar recipes, incremental development, and with column still blends being the majority of sales.

The rum world in the 1980s was a rather staid one, moving along very much as it had for years before. Major rum companies from around the Caribbean were issuing more or less the same rums they had been for decades – then as now, 40% ABV was practically a standard, age almost uniformly under ten years (if mentioned at all), and the market was full of familiar brands, similar recipes, incremental development, and with column still blends being the majority of sales.

As with all such general conditions, there were exceptions at the margins. Many small companies “made” rum for sale around the world – but they were really rebottlers and independents, not primary producers with sugar estates and/or distilleries of their own. Too, although 40% was a common sort of strength (especially in the United States), it was not an absolute. The French Caribbean islands made more than their fair share of rums around 50% ABV and rums made for export to European countries often boosted the strength to 43-48%

When it came to market domination, Bacardi was the undisputed leader, and lighter Spanish-style rums seemed to be everywhere – I even found them and not much else in Central Asian bazaars in the early 1990s. The great Asian houses like McDowell’s and Tanduay were unknown except in their region. Most rums in production at the time were considered mixing drinks at best, which was a state of mind deriving from the misconception that it was a pirate’s booze, a sailor’s hooch, a drink to have fun with…not something to be taken seriously. Not to be had by itself, or to be savoured on its own. Unlike, for instance, whisky.

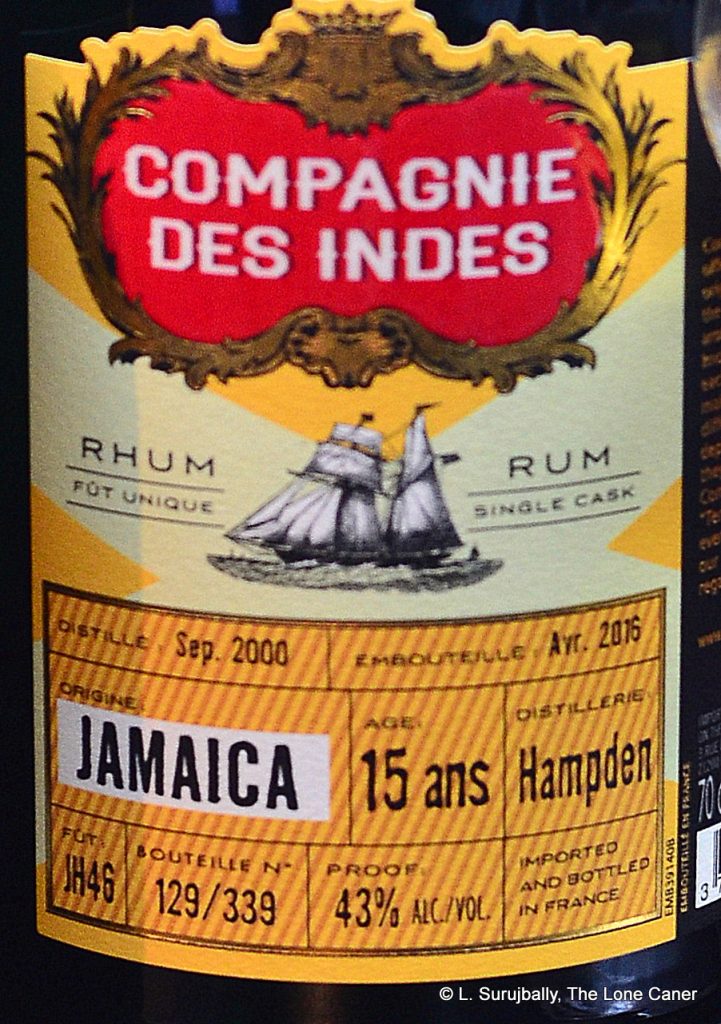

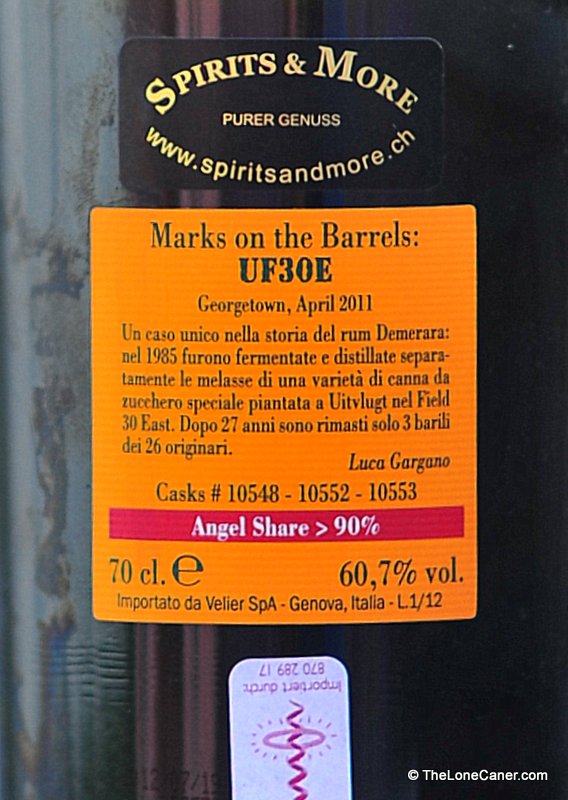

Although some independent bottlers issued more seriously aged rums in limited quantities, they didn’t expand production or really take it further – the market was a small one, and such bottlings were mostly bought by whisky aficionados and some hard core rum enthusiasts-cum-collectors, who were intrigued by the variations –people like Steve Remsberg, profiled here and here or Luca Gargano, or Martin Cate or the Burrs. Rum culture in the general public — both in perception and consumption — was primarily about cocktails, the mythmaking of Hemmingway-esque muscularity…today’s social-media-enabled rum clubs, where reviews of the latest bottling of a favoured company go up in days, hours or even minutes after formal release, where minute variations of favourite styles or individual rums are endlessly bickered over, and where discussions about additives erupt every other post, were not even a cloud on the horizon.

This is not to say a wide variety of rums was not being made – quite the opposite. South and Central America had a long and proud history of rum production. Companies like Varelas Hermanos, Vollmer, Zacapa, Zaya, Dictador, Travellers, Flor de Cana, Juan Santos, and Cartavio were issuing softly blended and solera-style rums since the early 1900s and some even predated the turn of the century. Cachacas had been made for hundreds of years in Brazil. In the East there were almost unknown rums from India and Thailand and Indonesia. Cuba had its national production arm sending rums to Scheer and began working hand in hand with Pernod Ricard to produce the Havana Club line in the 1990s; and while booted out of Cuba itself, Bacardi was selling rums by the tankerload globally (largely due to subsidies provided by the US government). The French islands, with their plethora of small and fiercely individualistic distilleries sold primarily to the European market (France in particular), and even with the slow demise of sugar and rum production, distilleries in Jamaica, Trinidad, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, Guyana, Antigua and Barbados (to list but some) struggled gamely on.

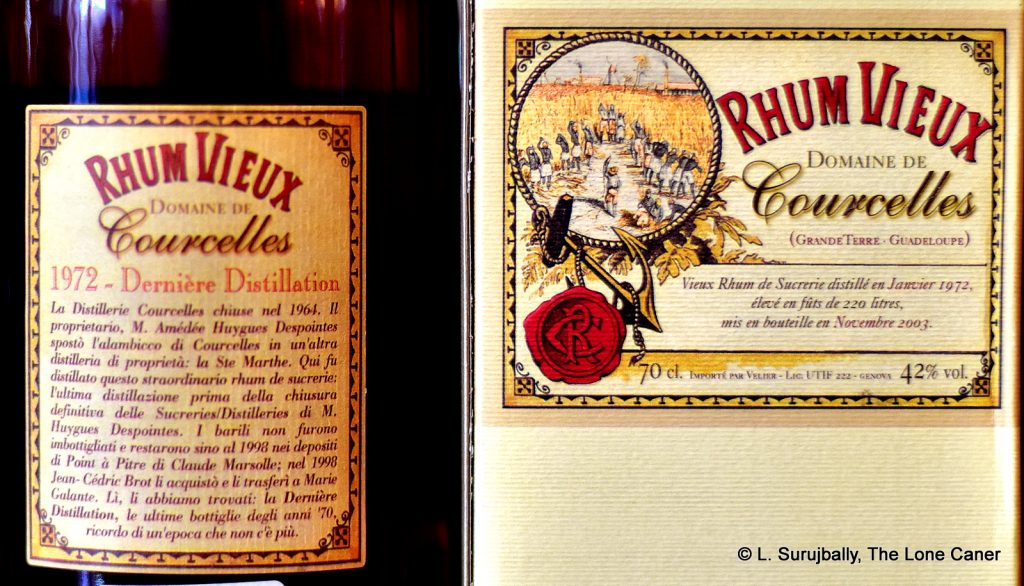

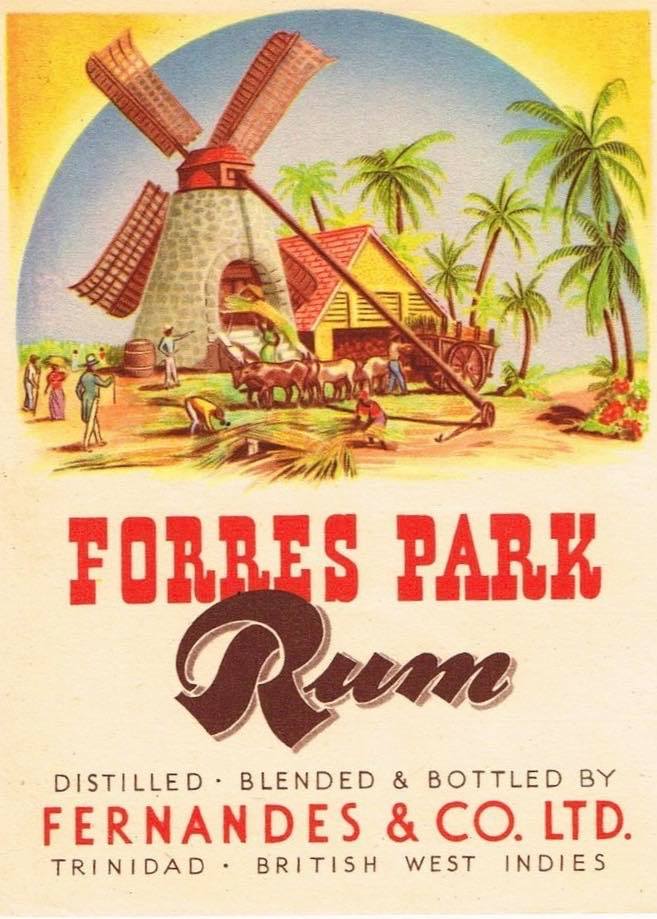

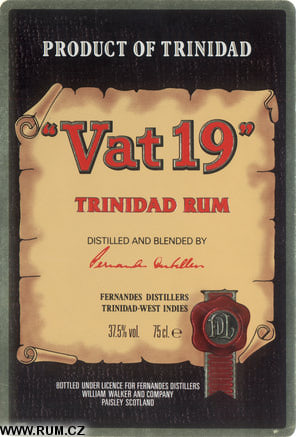

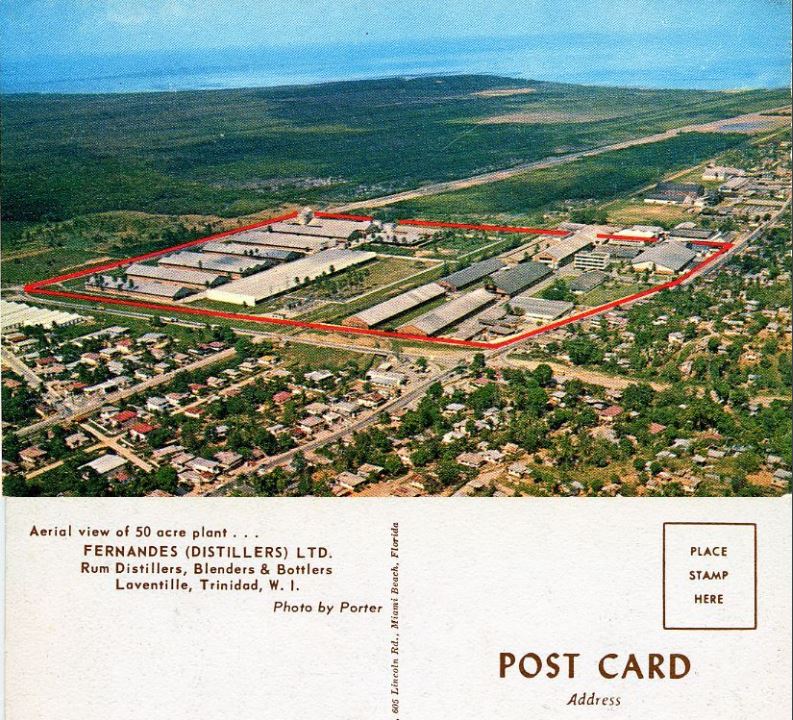

Aged rums made by primary producers from the pre-1990s eras were on the market, sure, and there was no shortage of them….but one had to look carefully for the specific trees in the forest (nowadays even more so when most exist in private collections or in memory alone). Fernandes Distillery in Trinidad made the Ferdi 10 Year Old from as far back as the 1930s and was still making it in the 1960s and 1970s; Appleton produced a 12 year old and a 20 year old from way back in the 1960s, issued a limited 25 year old in 1987, and old gaffers will remember the Dagger 8 Year Old and Three Dagger Jamaican 10 Year Old from J. Wray, also hailing to the 1930s; and going back even further in time, Jamaica at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition, London, 1886 by Sir Augustus J. Adderley lists 10, 15, 25 and 31 year old rums from merchant bottlers like D. Finzi & Co. and Wray and Nephew (before they acquired Appleton). I know there was an 18 year old “Old New England Rum” from the USA in 1934; Beenleigh in Australia made a five year old rum (and supposedly supplied the Royal Navy); Banks DIH in Guyana made a five year old as far back as the 1950s (though I don’t know when the 10 year old first appeared). La Favorite on Martinique had a ten year old back in the 1950s and 1960s, but like most agricole makers, were much more into millesime rhums, and while I’m sure the agricoles had more than my research uncovered, their naming convention of vieux, tres vieux and XO makes it difficult to see what is aged beyond, say, six to ten years. Most aged rums around the world seemed to be ten years old or less. A twenty year old was unheard of, thirty the stuff of dreams. (We had to wait until 1999 for the G&M 58 year old, another ten years for the Courcelles 37 year old).

Aged rums made by primary producers from the pre-1990s eras were on the market, sure, and there was no shortage of them….but one had to look carefully for the specific trees in the forest (nowadays even more so when most exist in private collections or in memory alone). Fernandes Distillery in Trinidad made the Ferdi 10 Year Old from as far back as the 1930s and was still making it in the 1960s and 1970s; Appleton produced a 12 year old and a 20 year old from way back in the 1960s, issued a limited 25 year old in 1987, and old gaffers will remember the Dagger 8 Year Old and Three Dagger Jamaican 10 Year Old from J. Wray, also hailing to the 1930s; and going back even further in time, Jamaica at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition, London, 1886 by Sir Augustus J. Adderley lists 10, 15, 25 and 31 year old rums from merchant bottlers like D. Finzi & Co. and Wray and Nephew (before they acquired Appleton). I know there was an 18 year old “Old New England Rum” from the USA in 1934; Beenleigh in Australia made a five year old rum (and supposedly supplied the Royal Navy); Banks DIH in Guyana made a five year old as far back as the 1950s (though I don’t know when the 10 year old first appeared). La Favorite on Martinique had a ten year old back in the 1950s and 1960s, but like most agricole makers, were much more into millesime rhums, and while I’m sure the agricoles had more than my research uncovered, their naming convention of vieux, tres vieux and XO makes it difficult to see what is aged beyond, say, six to ten years. Most aged rums around the world seemed to be ten years old or less. A twenty year old was unheard of, thirty the stuff of dreams. (We had to wait until 1999 for the G&M 58 year old, another ten years for the Courcelles 37 year old).

Anyway, much of the primary producers’ rum production went to Europe in bulk (a lot went to E&A Scheer, which was and remains one of the largest brokers buying rum stock in the world) and was then blended into European producers’ rums, of which there were many, none of which achieved any sort of lasting fame (unless it was the navy style of rum made by UK companies like Watsons for the local market). There were many small merchant bottlers, shops and back-street independents who released extremely limited and now-often-forgotten bottlings of aged expressions into the marketplace. And so the West Indian distilleries consolidated, shuttered, closed, changed focus, modernized, diversified, found new markets…and somehow the rum continued to flow.

Anyway, much of the primary producers’ rum production went to Europe in bulk (a lot went to E&A Scheer, which was and remains one of the largest brokers buying rum stock in the world) and was then blended into European producers’ rums, of which there were many, none of which achieved any sort of lasting fame (unless it was the navy style of rum made by UK companies like Watsons for the local market). There were many small merchant bottlers, shops and back-street independents who released extremely limited and now-often-forgotten bottlings of aged expressions into the marketplace. And so the West Indian distilleries consolidated, shuttered, closed, changed focus, modernized, diversified, found new markets…and somehow the rum continued to flow.

But underneath this relatively placid existence of blends and unquestioning rum-is-fun-no-questions-need-be-asked, several seemingly unrelated events occurred which were to lay the foundations of whole new directions for the rum world.

1992 and the El Dorado 15 Year Old

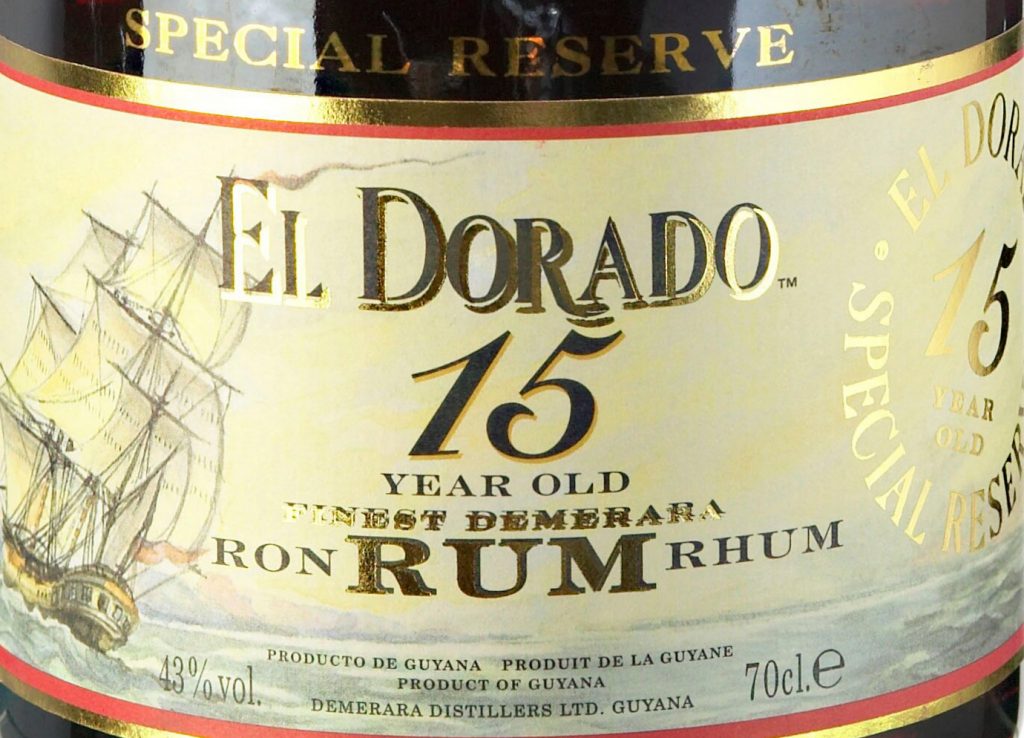

In 1992, what proved to be an enormously influential rum came on the scene – the El Dorado 15 Year Old and its brothers up and down the line, the 5, 12 and 21 and (later) the 25s. It may not seem so now, when so many aged brands are sold around the world, and where every distillery has a few in its portfolio. But it sure was then.

Bearing in mind the (very) abridged list of older rums mentioned above, it doesn’t entirely surprise me that whatever the age, few or none seemed to ever make a huge worldwide splash. The market wasn’t there, the connoisseurship was lacking, and information interchange was by magazines and snail mail, not the internet (see below). People just didn’t know enough and had few avenues open to self-education that characterizes today’s fanboys. Remember also, most of the aged rums were issued by small rebottlers in Europe or their agents in the producing countries/islands on behalf of the originating distilleries, and that kept outturn relatively small. Independents like Samaroli and Veronelli had been making such rums since the 1970s, and Scottish whisky makers and re-bottlers certainly issued their fair share, though they were rare in the pre-1992 era.

And a downside to the independents was that they didn’t always made it clear where they originated – bought directly from the distillery of origin, or through a European broker like Scheer. Only occasionally was it unambiguously stated where the ageing had taken place. They varied from expression to expression, and long term consistency was rare. They were not always specific, and commonly labelled as “aged” or “country” rums – Superior Rum, Extra Old Rum, Barbados Aged Rum, Guyanese Rum, Jamaican Rum, and so on. The concept of making the estate the selling point was almost ignored. Many were, in fact, blends of uncertain age, mixing several estates’ marques into a single product. The consumer was certainly not helped to make an informed choice in the matter because exclusivity was the key selling point – you took what you got, trusted the skill of the producing company, and were grateful.

What made the El Dorado 15 (and its brothers) so seminal is that for the first time and over an extended period, a rum was made the same way every time, with an outturn not of a few hundred bottles, but in the tens and hundreds of thousands, year in and year out. Consumers were getting a true fifteen year old rum of distinctive taste and consistent profile, not some supposedly exclusive and high-priced limited edition of a “Manager’s Reserve” or “Private Family Stock” or “My Dog Bowser’s Anniversary Blend.” Now anyone could buy this rum, which was a cut above the ordinary, had really cool antecedents, and was an absolute riot to drink neat. Best of all, the El Dorado 15 was approachable – it retailed at an affordable price, had a taste the average consumer would like (toffee, caramel, licorice, citrus and raisins remain in the core profile), could be mixed, swilled or sipped, had great marketing and was issued an unthreatening 40%. The greater rum drinking audience went ape for it.

What made the El Dorado 15 (and its brothers) so seminal is that for the first time and over an extended period, a rum was made the same way every time, with an outturn not of a few hundred bottles, but in the tens and hundreds of thousands, year in and year out. Consumers were getting a true fifteen year old rum of distinctive taste and consistent profile, not some supposedly exclusive and high-priced limited edition of a “Manager’s Reserve” or “Private Family Stock” or “My Dog Bowser’s Anniversary Blend.” Now anyone could buy this rum, which was a cut above the ordinary, had really cool antecedents, and was an absolute riot to drink neat. Best of all, the El Dorado 15 was approachable – it retailed at an affordable price, had a taste the average consumer would like (toffee, caramel, licorice, citrus and raisins remain in the core profile), could be mixed, swilled or sipped, had great marketing and was issued an unthreatening 40%. The greater rum drinking audience went ape for it.

Within a few years, just about every primary rum producer with a well known brand caught the wave, and the 1990s and 2000s saw an explosion of older rums. Companies all over the western hemisphere rushed to bring out aged expressions, and such rums soon became staples of many companies’ lines (and Appleton finally got the respect for its 12 YO it deserved, as well as beginning the regular issuing of older variations). The South and Central American and Spanish Caribbean islands’ rum makers took their time with it: they were blenders for the most part, a few solera-style makers, and they saw no reason to go full bore in this direction (many still don’t). The French islands with their millesime approach and their own ideas on what constituted a good aged rum dabbled their toes, but with a few exceptions (I saw a 12 YO dating back to the 1970s once, so they certainly existed) they rarely ventured over ten years old – and bearing in mind the quality of what they achieved and the recognition their brands already had and have always maintained in their primary markets, it was and remains hard to fault them for this choice.

So the aged rum market almost by default landed, and has remained, with some exceptions, in the British West Indies, led by Appleton and also DDL, the company whose work would produce the next great wave of rums ten years down the road….but not under its own banner.

Books

One development that also raised the profile of rum was the publishing of three books — two in the early 1990s, the other nearly ten years later. To some extent they have been overtaken by events, yet they remain quiet classics of the genre, and carried with them not only the promise of other books written in the decades that followed, but a resurgence of interest in rums as a whole. They remain cornerstones of the literature, not least because they were among the first to try and provide a deeper background to the variety of rums represented without overwhelming the readers in technical minutiae of the rum-making process most neither wanted nor understood.

Released in 1995, Ed Hamilton’s book “Rums of the Eastern Caribbean” was a rich and varied survey of as many distilleries and rums as Mr. Hamilton found the time to visit and try over many years of sailing around the Caribbean. Because of its limited focus, it lacked a global perspective, but it was a treasure trove of information of the rum producing world in the eastern Caribbean at that time, it was based on solid first hand experience, and many rum junkies who make distillery trips part of their overall rum education are treading in his footsteps. If nothing else, it elevated the knowledge of the curious and made it clear that there was an enormous breadth in rums, so much so that historical info aside, anyone could find something to please themselves. (It was followed up in 1997 by another book called “The Complete Guide to Rum”).

Dave Broom’s 2003 book “Rum” was a coffee-table sized book that combined narrative and photographs, and included a survey of the rum producing nations and islands and regions to that time. It was weak on soleras, missed independents altogether and almost ignored Asia, but had one key new ingredient – the introduction and codification of rum into styles. Then as now, the debate over how to classify rum was a problem. Colour was still used as a main marker and gradation of type (the additives and coloration debate had yet to reach wide attention, and was all but unknown to the drinking public), stills were not considered a way to distinguish rums. Mr. Broom’s contribution to the field was to at least attempt to stratify rums: in his case, regions that had broad similarities of production and profile: Jamaican, Guyanese, Bajan, Spanish and French island (agricole) styles. Cachacas were not brought into the classification and there was no real way to incorporate multi-regional blends or rums from outside the system (like, oh, Australia) – but it was an remains enormously influential, though by now somewhat dated and overtaken by events (he issued a follow-up “Rum: The Manual” in 2016, the same year as “Rum Curious” by Fred Minnick came out).

What these books did was make rum interesting and more appreciated in the eyes of the larger public, in a pre-internet world where whisky prices were just starting to climb. They showcased something of the variety that rum provided, and educated many neophyte rum lovers into the foundations of their favourite drink. It showed them the varieties and differences and production methods that allowed a more sophisticated understanding of the spirit. Rum was clearly not just some blended bathtub moonshine for the sweet-toothed who didn’t appreciate a single malt, or a bland and boring mixing agent — but a spirit with a long and technically rigorous, geographically broad-based history that deserved mention, if not respect.

The Internet

The Internet

To some extent the remarks here are a subset of larger cultural shifts around the world which were enabled by the internet and the world wide web itself. Access was available in 1995, but nowhere near as ubiquitous as it became over the subsequent decades. The internet enabled web pages, those pages enabled blogs, blogs became review sites and fora for interaction — and all of it created a communications revolution for rum lovers. What this allowed and promoted was a new understanding of the spirit, a grasp of its enormous stylistic range and geographical dispersion, as well as quick dissemination of information on rums, brands, companies, personalities, reviews, and opinions. It’s no accident that the sugar imbroglio (see a brief discussion in Part 3) arose only after the internet permitted such exponential interaction and news-exchange among drinkers; or that the first rum festivals began springing up just as the first review sites did, in the mid 2000s. The importance and impact of the web on rum appreciation simply cannot be overstated.

It took more time for the first write ups of Velier to come out the door on such websites, but before that happened there came one website that proved to be enormously influential, which all bloggers from that era remember.

Ed Hamilton and the Ministry of Rum

It took years after its launching in 1995 for the Ministry of Rum to acquire the central status it held for the next decade, and in its heyday it was one of the key places for aficionados to meet and share information (Capn Jimbo’s site was the other), and likely the most popular. While it possessed a fair amount of articles and searchable information on distilleries, brands and countries – a first at that time, and a godsend to the researchers – the real basis for its influence and popularity was the forum and discussion area, and, to a lesser extent, the Connoisseur’s Cabinet where occasional reviews would be posted (with Ed’s permission – and for the record he refused it to me when I asked after passing review #50, noting – correctly – that too many new and aspiring writers folded after a couple of years). At its peak, there would be new discussion threads and posts springing up daily, sharing information, raising issues, offering advice and opinions. Even now in 2018 there’s a steady trickle of people on that site, posting “Hi I’m a new rum lover from ____”.

In these days of Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, Tumblr, Pinterest, blogs, aggregators, instant messaging and full-time online presences, it’s difficult to remember how groundbreaking this trend actually was. Now rum lovers did not have to create websites (a difficult and often confusing task in the early 2000s) and then hope that they would be found – they could simply post on the Ministry. Many of the older names in the rum writing game started their careers by commenting – extensively – here. This one original website did more than most other avenues to help disseminate information and news about rum, and introduced the vocal, dedicated fans to one another, a process that has accelerated with the advent of social media.

Independent Bottlers / Private Labels

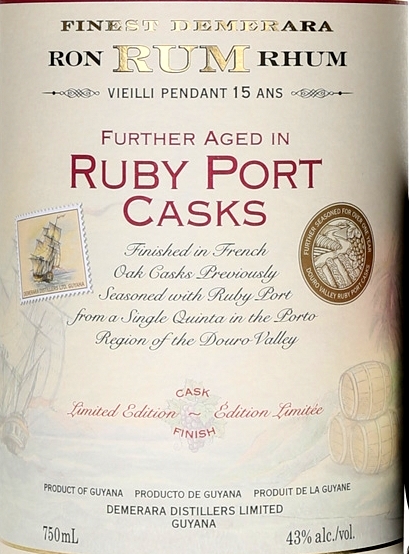

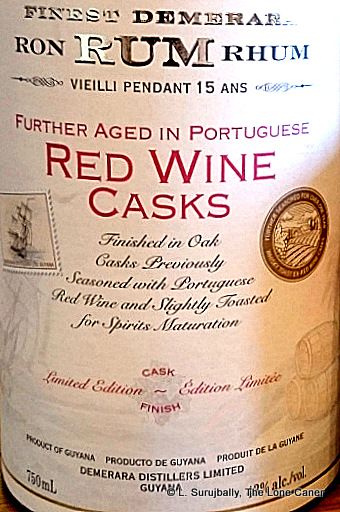

If you put aside the 151 overproofs that Bacardi, Lemon Hart, Cruzan, Don Q, Goslings, Matusalem and a handful of others were releasing, the limited edition “cask strength” market was all but nonexistent until a decade ago, and these 75.5% mastodons were all you got. All were considered cocktail bases, not rums in their own right: they were certainly not premiums. Such cask-strength rums as were considered a cut above the ordinary were mostly issued by independents, not by major producers (who limited themselves to powerful cocktail mixers like the 151s), and the independents weren’t looking to make overproofs but echoed whisky maker’s full-proof ethos.

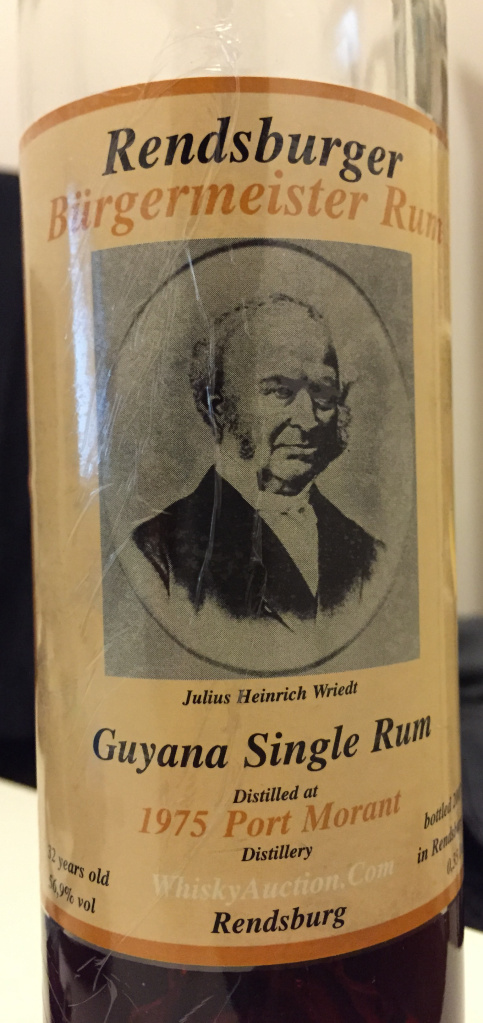

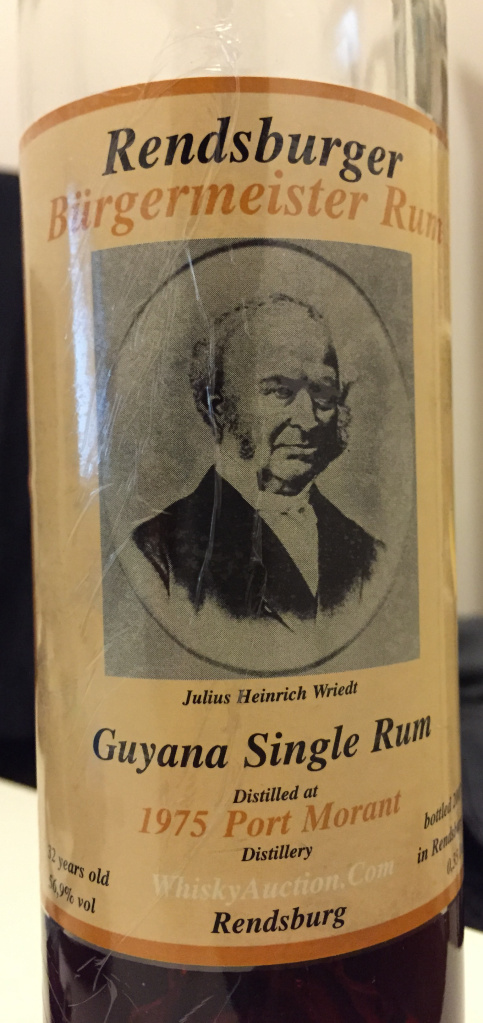

Almost alone in the world, then, the Europeans issued a few high-proof bottlings, released by re-bottlers and spirits companies such as Cadenhead, Gordon & MacPhail, A.D. Rattray, Berry Brothers & Rudd among others; as well as smaller concerns like Illva Saronno (Italy), Vaughan-Jones (UK), EH Keeling (UK), Antoniazzi (Italy), John Milroy (UK), Frederic Robinson (UK), Austin Nichols (USA), A.A. Baker (US), Nicholson (UK), Watson’s (UK), Sangster, Baird-Taylor, Gilbey & Matheson, Henry & White, Lemon Hart, (among many many others). The Germans had their own such companies such as those around Flensburg (Rendsburger, Dethleffson and Berentzen Brennereien for example, who made long forgotten rums under brand names like Asmussen, Schmidt, Nissen, Anderson and Sonnberg). And there was a scattering here and there, like Walter Reid in Australia, la Martiniquaise and Bardinet in France, a smattering of Americans…and quite a few small outfits in Italy.

It was a lonely occupation for these rebottlers and small operations, because the rums they created – whether aged, blended, high-proofed or all these at once – never really sold very well even at standard strength. Fabio Rossi, who started Rum Nation in 1999, told me it took more than two years to sell the first Supreme Lord and Demerara series of rums he started off with; and as recently as 2012, one could get the entire Velier Caroni outturn to that point for a couple thousand euros (on ebay’s Italian site), a situation which could certainly not happen today. It was the hard-to-shake perception of rum as not being “premium” that was at the bottom of it, a situation it took another ten years to rectify, and it was the small, nimble companies who we now refer to as “independents” who led the way.

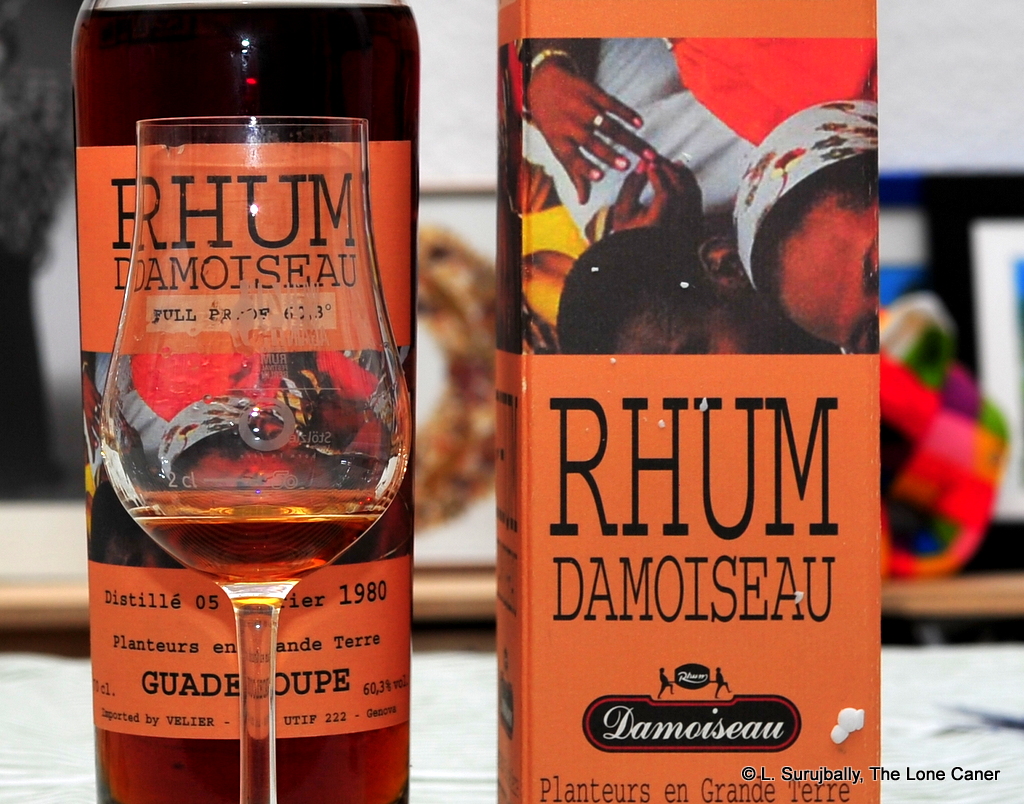

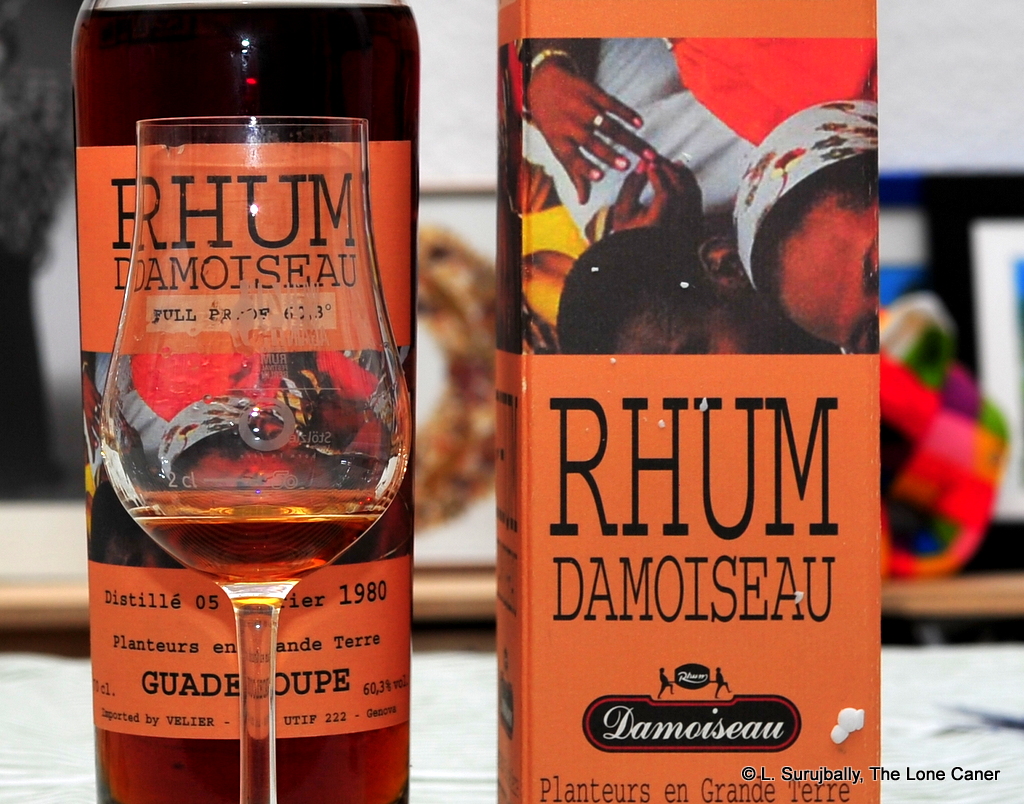

A word should be spared for the work of the Martinique and Guadeloupe rum producers which don’t conform to the title of independents, but which also laid some of the groundwork for the renaissance of strong and singular rums that was about to take off. These small estate distilleries sold their rums primarily on the local market and exported to France through their own distribution arms there. Among all their lightly aged rums and blends and whites, they also and occasionally produced millesimes which were specific years’s limited productions, bottled when such outturns were considered a cut above the ordinary. And while these were never very consistent (each one was different from the last), never really aged beyond all reason, only occasionally issued beyond 50% – they did showcase that a particular year’s output of rum might be considered a connoisseur’s drink and could be said to be grand-uncles of the single barrel releases by others. And that is why the Clement 1952 and 1976, the Damoiseau 1953, Bally 1939 and 1960 and 1970, Montebello 1948 remain hugely expensive, yet still-sought-after exemplars of craft rum making by the producers of Martinique and Guadeloupe.

A word should be spared for the work of the Martinique and Guadeloupe rum producers which don’t conform to the title of independents, but which also laid some of the groundwork for the renaissance of strong and singular rums that was about to take off. These small estate distilleries sold their rums primarily on the local market and exported to France through their own distribution arms there. Among all their lightly aged rums and blends and whites, they also and occasionally produced millesimes which were specific years’s limited productions, bottled when such outturns were considered a cut above the ordinary. And while these were never very consistent (each one was different from the last), never really aged beyond all reason, only occasionally issued beyond 50% – they did showcase that a particular year’s output of rum might be considered a connoisseur’s drink and could be said to be grand-uncles of the single barrel releases by others. And that is why the Clement 1952 and 1976, the Damoiseau 1953, Bally 1939 and 1960 and 1970, Montebello 1948 remain hugely expensive, yet still-sought-after exemplars of craft rum making by the producers of Martinique and Guadeloupe.

However, it’s the Italian companies which were to some extent key to the emergent Age, because although many were simply importers and distributors, some also dabbled in blending and reissuing of rums under their own labels. They created the culture of Italian independents that dated back to the 1960s when sweetened “rhum fantasias” were in vogue in Italy, produced by companies like Pagliarini, Toccini and Seveso; they were accompanied by importers and rebottlers (Veronelli, Soffiantino, Martinazzi, Antoniazzi, Pedroni, Illva Saronno, and Guiducci are just a few examples) which led to their more successful inheritors, Samaroli, Moon Imports, Silver Seal and Velier, just about all who started with single barrel whiskies before turning their attention to rums.

Which leads us to that little importing company from Genoa, and its owner – Luca Gargano.

Luca Gargano and Velier

Luca Gargano and Velier

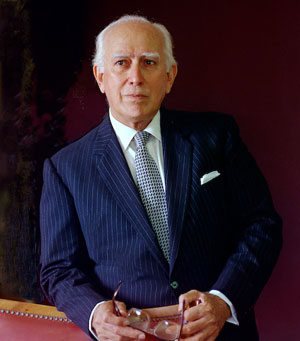

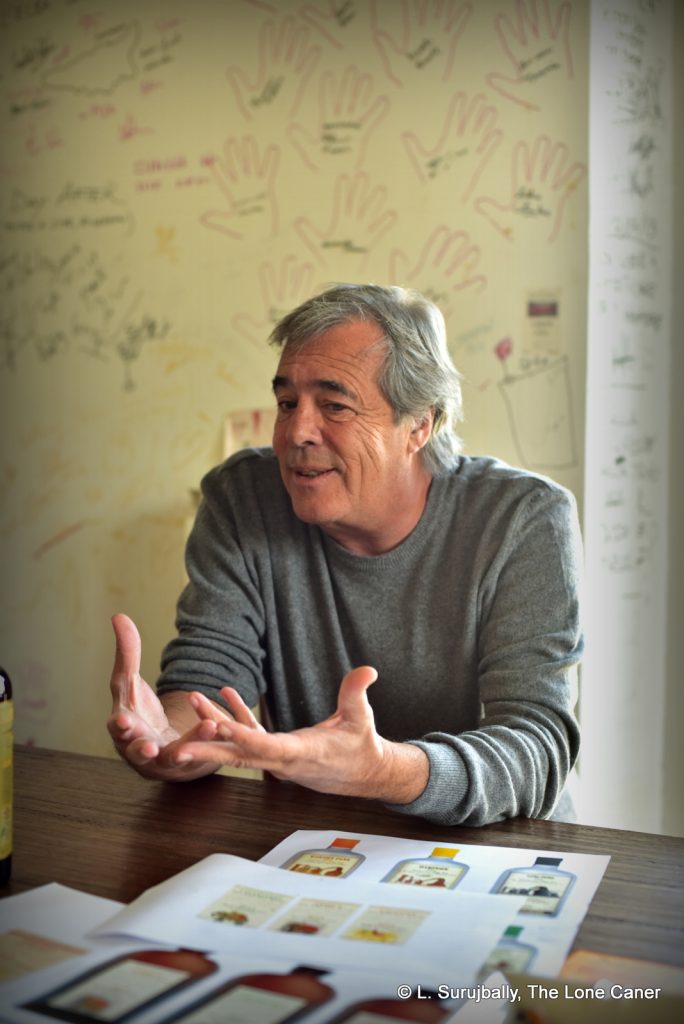

In the 1980s, Velier was a small family-owned Genoese spirits distributor with perhaps a quarter million dollars a year turnover and a staff of less than ten. It had been formed in 1947 by Casimir Chaix and concerned itself primarily with importing and distributing wines, spirits, brandy, tea and cocoa. Luca Gargano changed all that by buying it in 1986, when he was still only in his twenties. He had been a very young brand ambassador for St. James (from Martinique) and the experience had left him with a deep appreciation for rums, especially artisanal ones. When the time came for him to start a company of his own, he used Velier as a vehicle for his deeply held beliefs and the outpouring of his ideas.

Luca, who came from a family that was both close to the land and well connected in Italian commercial and political society, had spent years traversing the Caribbean in his time with St. James. His filial connection with traditional farming and agriculture, his observation of the way technology was changing the world (not necessarily for the better), his feelings about politicians and the slanted biases of the news, led him to create his now-famous Five Principles: nothing happens in specific chunks of time; newspapers and the media are there for sales and not truth; politicians are in it for themselves; telephones tie you to themselves but offer little except conversations that were better and more enjoyably conducted in person; and why stress out about driving a car when one can use taxis? And as a consequence he stopped watching TV, didn’t waste his time with newspapers or personal vehicles, chucked away his watch and never bothered with a cell phone of his own.

But there was a sixth principle, not often stated, yet deeply held. And that was that food and drink should be as natural as possible, organic, free from the interferences of technology, fresh from the land. When one applies that to food it’s one thing, but few before him sought to apply the concept to rums (except perhaps out of necessity). He felt that rum should be bottled as it either came off the stills or out of the ageing barrel without further messing around. He may have known more than we did in those more innocent times, because although it is now common knowledge that many old favourites which came to the market in the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s were dosed with additives, back in the day there was a lot more trust going around between consumers and producers.

But there was a sixth principle, not often stated, yet deeply held. And that was that food and drink should be as natural as possible, organic, free from the interferences of technology, fresh from the land. When one applies that to food it’s one thing, but few before him sought to apply the concept to rums (except perhaps out of necessity). He felt that rum should be bottled as it either came off the stills or out of the ageing barrel without further messing around. He may have known more than we did in those more innocent times, because although it is now common knowledge that many old favourites which came to the market in the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s were dosed with additives, back in the day there was a lot more trust going around between consumers and producers.

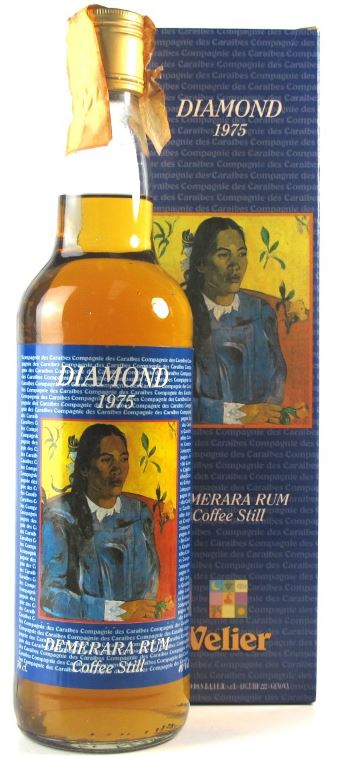

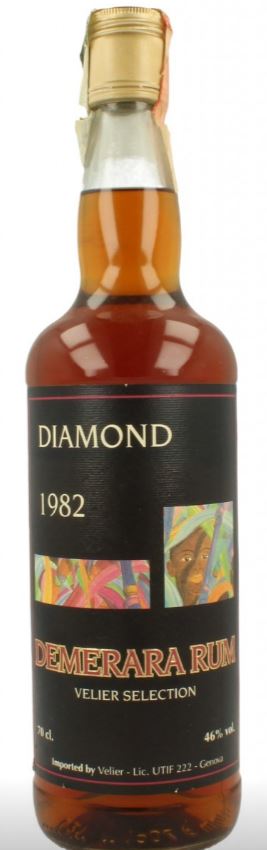

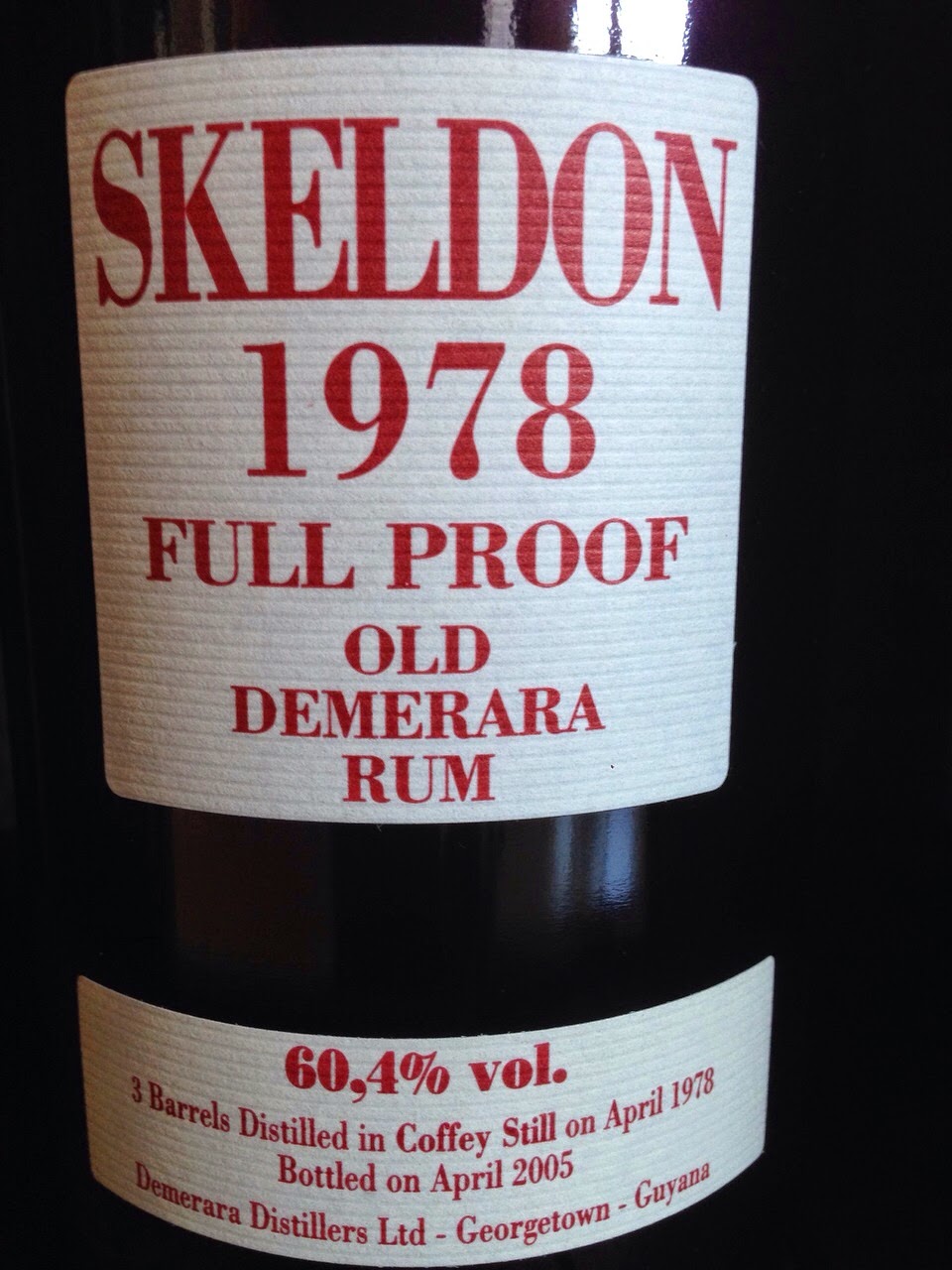

Whatever the case, Luca wanted to put his name on pure rums that were as close to the still as possible, and if aged, fresh out of the barrel. He started by finding some old Guyanese rums, continentally aged, and put them out the door in 1996, with a further set of three in 2000. Neither entirely satisfied him, because the first set was diluted down to 40% and the second to 46%. A third series was released in 2002, also at 46% by which time he was in a better position to negotiate barrels with DDL.

And he needed to go further with his ideas on rums, because these early Demerara rums, to put it bluntly, made no mark, no splash, and fell flat. They sold, but not well (I’ve been able to pick a few up as late as 2017), and in any event were not exactly what he wanted. The continental ageing and dilution in particular dissatisfied him — he felt something of the intrinsic character of the underlying distillate that showcased the stills and their uniqueness, had been lost. He pulled in his horns, gave it some thought and was much more personal and involved in his future selections. He wanted to issue a rum that was at the full proof of the barrel, not some milquetoast please-the-most rum which he himself did not appreciate.

He was still wrestling with whether this was a workable commercial concept when he found a stored 18 year old rum at Damoiseau in Guadeloupe which was so spectacular, that he released it at 60.3% ABV in 2002, crossing his fingers as he did so. The success of the Damoiseau 1980 made it clear that among people who knew their stuff, such rums would sell and find their own audience and he not limit himself in the future, as he had with the past three releases.

He was still wrestling with whether this was a workable commercial concept when he found a stored 18 year old rum at Damoiseau in Guadeloupe which was so spectacular, that he released it at 60.3% ABV in 2002, crossing his fingers as he did so. The success of the Damoiseau 1980 made it clear that among people who knew their stuff, such rums would sell and find their own audience and he not limit himself in the future, as he had with the past three releases.

He issued no new rums for the next three years, and then emerged with the next outturn in 2005. Four rums, one of them almost a legend. The Age can be said to have begun here.

In Part 2 I’ll look at the rums of the Age, and in Part 3 make some points about the aftermath of their issue and revisit some of these “historical” figures to see where they’re at in 2018.

Notes

Much of this is written based on my own writing and thinking and life experiences, though I have dipped into other bloggers’ published work here and there (like Matt Pietrek’s essay on Scheer and Marco Freyr’s background essays on Barrel Aged Mind). The research done in writing my own rum reviews and company biographies for nearly ten years has provided much of the remainder.

It’s hard to find people whose memories stretch back that far, to recapture the flavour of what the pre-1990s rum world was like – so some artistic license has been used to describe those times, though the facts are as accurate as I could make them.

The section on older aged rums and independents is by no means exhaustive. It’s surprising how difficult it is to find exactly when a particular ten- or twelve- or fifteen-year-old rum first emerged on the scene, and to find discontinued variations becomes an exercise in real Holmesian diligence. I used my own photographs from Velier’s 4000+ rum warehouse for some of the examples in this section, and I would be remiss if I did not mention Peter’s Rum Labels in Czechoslovakia, which is an amazing resource, the best one of its kind in the world. I hope that people with large rum collections built up over many decades will one day allow people like me access to their stocks – to photograph and catalogue them (and maybe even to try a few) and for sure to write about them, as I do for the Rumaniacs. Too much history is being lost just because we don’t know enough, forgot too much, and never thought to record things properly.

Needless to say, if any mistakes or errors (especially of omission) are noted, please let me know and I’ll make amendments where required.

Nose – In a subtle way this is different from the others. It opens with aromatic tobacco, white almond-stuffed chocolate and nail polish before remembering what it’s supposed to be and retreating to the standard profile of salty caramel, molasses, vanilla, cherries, raisins, lemon peel and oak, quite a bit of oak, all rather sere.

Nose – In a subtle way this is different from the others. It opens with aromatic tobacco, white almond-stuffed chocolate and nail polish before remembering what it’s supposed to be and retreating to the standard profile of salty caramel, molasses, vanilla, cherries, raisins, lemon peel and oak, quite a bit of oak, all rather sere.

Nose – Leaving aside a slight sweetish note (which I suppose is to be expected, though still not entirely welcome), it noses relatively darker and richer and fruitier than just about all the others except the “Dry”…within the limits of its strength and mild adulteration. Peaches, raisins, cinnamon, cloves, caramel, peanut butter, cherries in syrup and candied oranges, even a little bitter chocolate. It’s all rather delicate, but quite pleasant.

Nose – Leaving aside a slight sweetish note (which I suppose is to be expected, though still not entirely welcome), it noses relatively darker and richer and fruitier than just about all the others except the “Dry”…within the limits of its strength and mild adulteration. Peaches, raisins, cinnamon, cloves, caramel, peanut butter, cherries in syrup and candied oranges, even a little bitter chocolate. It’s all rather delicate, but quite pleasant.

Nose – At first there didn’t seem to be much of anything there, it was so mild as to be lightly flavoured alcohol. But after some minutes it got into gear and revved up some, with a solid core of light brown sugar, molasses, salt caramel, some sweet soya. Not much deep fruitiness here, just light grapefruit, bananas and nuttiness, and sweet white chocolate.

Nose – At first there didn’t seem to be much of anything there, it was so mild as to be lightly flavoured alcohol. But after some minutes it got into gear and revved up some, with a solid core of light brown sugar, molasses, salt caramel, some sweet soya. Not much deep fruitiness here, just light grapefruit, bananas and nuttiness, and sweet white chocolate.

Nose – This has a light, sweet, almost delicate series of smells. There are acetones, flowers and some faint medicinal, varnish and glue aromas floating around (I liked those – they added something different), and initially the rum noses as surprisingly dry (another point I enjoyed). These then morph gradually into a more fruity melange – tinned cherries in syrup, ripe pears, pineapples, watermelons – while remaining quite crisp. It also hinted at salted caramel, crunchy peanut butter, breakfast spices and a little brine, and the balance among all these seemingly competing elements is handled really well.

Nose – This has a light, sweet, almost delicate series of smells. There are acetones, flowers and some faint medicinal, varnish and glue aromas floating around (I liked those – they added something different), and initially the rum noses as surprisingly dry (another point I enjoyed). These then morph gradually into a more fruity melange – tinned cherries in syrup, ripe pears, pineapples, watermelons – while remaining quite crisp. It also hinted at salted caramel, crunchy peanut butter, breakfast spices and a little brine, and the balance among all these seemingly competing elements is handled really well.

Nose – Somewhat dry and redolent of sawdust, accompanied by delicate flowers an acetones. Quite solid and lightly sweet, and deserves to be left to stand for a while, because after some minutes the molasses, caramel and light licorice notes characteristic of the line begin to make themselves felt, and are then in their turn dethroned by a deep fruitiness of ripe cherries, blackcurrants, plums, raisins and black grapes almost ready to spoil. In the background there’s some leather and citrus, neither strong enough to make any kind of serious impression.

Nose – Somewhat dry and redolent of sawdust, accompanied by delicate flowers an acetones. Quite solid and lightly sweet, and deserves to be left to stand for a while, because after some minutes the molasses, caramel and light licorice notes characteristic of the line begin to make themselves felt, and are then in their turn dethroned by a deep fruitiness of ripe cherries, blackcurrants, plums, raisins and black grapes almost ready to spoil. In the background there’s some leather and citrus, neither strong enough to make any kind of serious impression.

On the palate, I didn’t think it could quite beat out the CdI Worthy Park (which was half its age, though quite a bit stronger); but it definitely had more force and more uniqueness in the way it developed than the Longpond and the Mezans. It started with cherries, going-off bananas mixed with a delicious citrus backbone, not too excessive. After ten minutes or so it opened further into a medium sweet set of fruits (peaches, pears, apples), and showed notes of oak, cinnamon, some brininess, green grapes, all backed up by delicate florals that were very aromatic and provided a good background for the finish. That in turn glided along to a relatively serene, slightly heated medium-long stop with just a few bounces on the road to its eventual disappearance, though with little more than what the palate had already demonstrated. Fruitiness and some citrus and cinnamon was about it.

On the palate, I didn’t think it could quite beat out the CdI Worthy Park (which was half its age, though quite a bit stronger); but it definitely had more force and more uniqueness in the way it developed than the Longpond and the Mezans. It started with cherries, going-off bananas mixed with a delicious citrus backbone, not too excessive. After ten minutes or so it opened further into a medium sweet set of fruits (peaches, pears, apples), and showed notes of oak, cinnamon, some brininess, green grapes, all backed up by delicate florals that were very aromatic and provided a good background for the finish. That in turn glided along to a relatively serene, slightly heated medium-long stop with just a few bounces on the road to its eventual disappearance, though with little more than what the palate had already demonstrated. Fruitiness and some citrus and cinnamon was about it.

When the Scandinavians started publishing their results, the roof blew off — it quite literally changed the rum landscape overnight. For the first time there was proof — clear, testable, incontrovertible

When the Scandinavians started publishing their results, the roof blew off — it quite literally changed the rum landscape overnight. For the first time there was proof — clear, testable, incontrovertible  The El Dorado 15 remains a staple of the rum drinking world to this day in spite of its now well-publicized dosage. It has received much opprobrium for the lack of disclosure (DDL never commented on the matter of dosage until an interview with Shaun Caleb in 2020, and for the record the practice is being phased out) and has slipped somewhat in people’s estimation to being a second tier aged product. Yet it remains enormously popular and is a perennial best seller, a rum many new entrants to the field refer to as a touchstone, even though DDL has moved to colonize the space Velier pioneered and begun issuing cask strength limited bottlings from the stills themselves in 2016 (the

The El Dorado 15 remains a staple of the rum drinking world to this day in spite of its now well-publicized dosage. It has received much opprobrium for the lack of disclosure (DDL never commented on the matter of dosage until an interview with Shaun Caleb in 2020, and for the record the practice is being phased out) and has slipped somewhat in people’s estimation to being a second tier aged product. Yet it remains enormously popular and is a perennial best seller, a rum many new entrants to the field refer to as a touchstone, even though DDL has moved to colonize the space Velier pioneered and begun issuing cask strength limited bottlings from the stills themselves in 2016 (the

As noted in Part 1, after a few years of developing the company and broadening its portfolio, Velier began its move to craft spirits in 1992 (which may not be a coincidence), by beginning its selection of barrels of rum for its brand. This led, in 1996, to the issuance of three Guyanese rums – all issued at 40% (see next paragraph) and using a third partly bottler (Thompson & Co.). All were continentally aged.

As noted in Part 1, after a few years of developing the company and broadening its portfolio, Velier began its move to craft spirits in 1992 (which may not be a coincidence), by beginning its selection of barrels of rum for its brand. This led, in 1996, to the issuance of three Guyanese rums – all issued at 40% (see next paragraph) and using a third partly bottler (Thompson & Co.). All were continentally aged. Luca was dissatisfied with this, and four years later tried again, with three more rums from Guyana. These were bottled by a Holland-based subsidiary of DDL themselves (called Breitenstein), because by this time Velier’s association with DDL had become much firmer and it was felt to be more cost effective – though they remained continentally aged. Of particular note was Luca’s find of the LBI marque, quite rare, though which still produced it remains an open question. The Enmore also comes in for mention because of its strength – it was the first attempt to issue at full proof…why he did not follow on from this concept here is unknown, but considering that the

Luca was dissatisfied with this, and four years later tried again, with three more rums from Guyana. These were bottled by a Holland-based subsidiary of DDL themselves (called Breitenstein), because by this time Velier’s association with DDL had become much firmer and it was felt to be more cost effective – though they remained continentally aged. Of particular note was Luca’s find of the LBI marque, quite rare, though which still produced it remains an open question. The Enmore also comes in for mention because of its strength – it was the first attempt to issue at full proof…why he did not follow on from this concept here is unknown, but considering that the

2005 and 2006 together saw the issuance of not only eight different Guyanese rums but nine and eight Caronis respectively. None of these received especially wide acclaim or attention, though my feeling is that the 1991 Blairmont was definitely one of the better rums I’ve tried from the stable and the one occasion I tried (without notes) the PM 1993, it was equally impressive, though relatively young compared to its siblings issued in those two years.

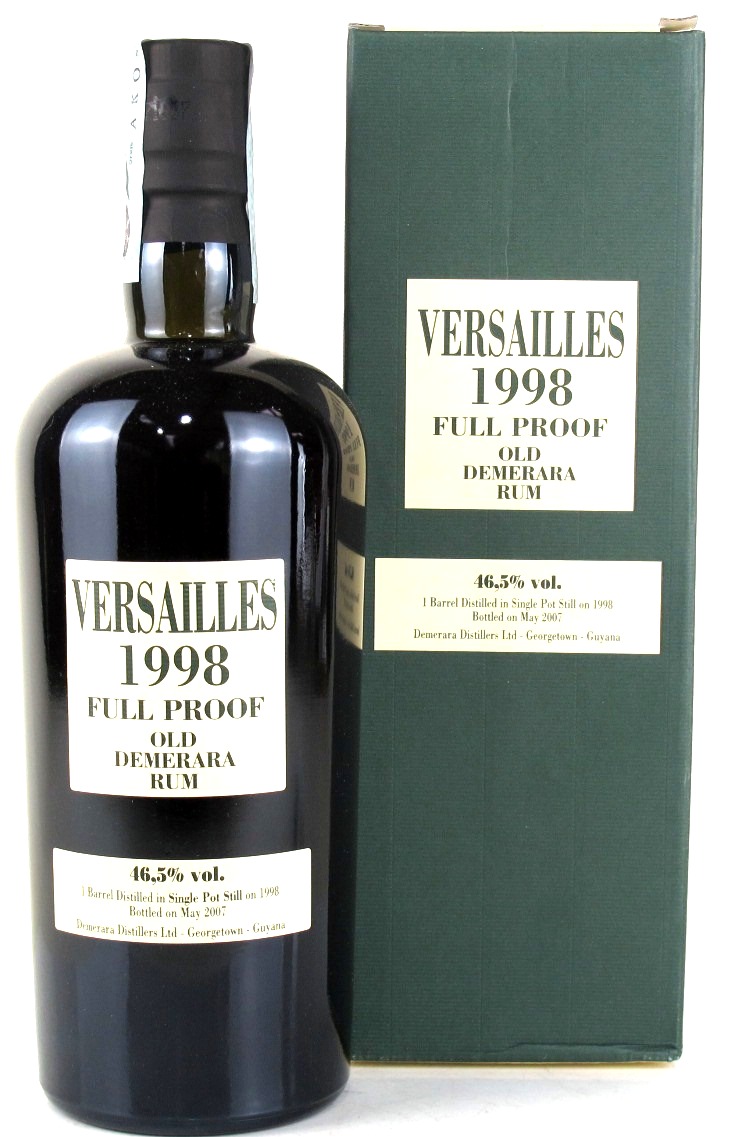

2005 and 2006 together saw the issuance of not only eight different Guyanese rums but nine and eight Caronis respectively. None of these received especially wide acclaim or attention, though my feeling is that the 1991 Blairmont was definitely one of the better rums I’ve tried from the stable and the one occasion I tried (without notes) the PM 1993, it was equally impressive, though relatively young compared to its siblings issued in those two years. 2007 was an odd year, when everything issued was under ten years old, which may just have been a function of what was put in front of Luca to inspect and select. The first Versailles rum since 1996 was issued in 2007, and somehow another LBI rum was found – it would prove to be the last.

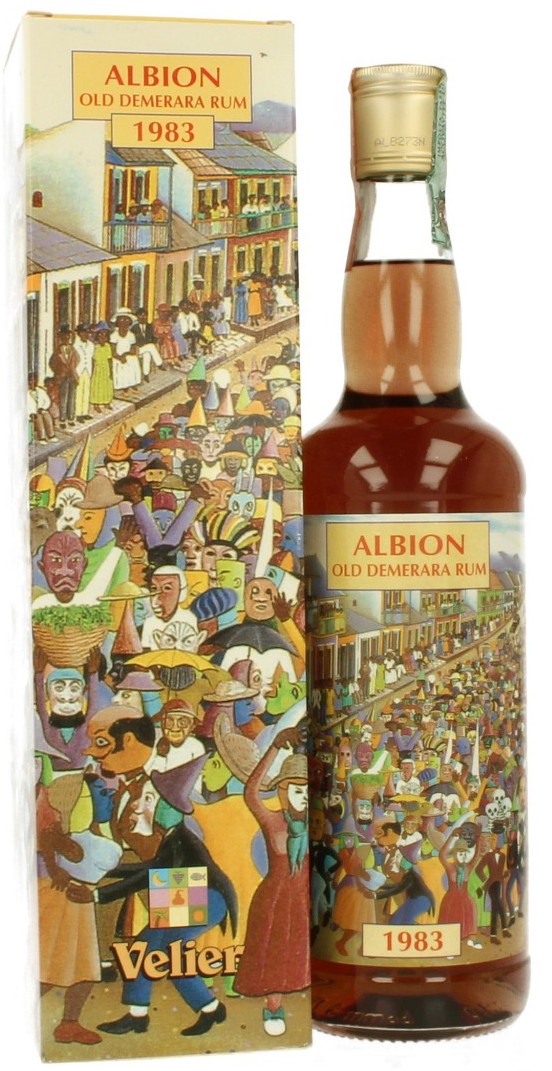

2007 was an odd year, when everything issued was under ten years old, which may just have been a function of what was put in front of Luca to inspect and select. The first Versailles rum since 1996 was issued in 2007, and somehow another LBI rum was found – it would prove to be the last. When it came to releases, 2008 was a banner year for the company, when eight Demerara rums were issued at once. Yet widespread acceptance remained elusive: costing out at over a hundred euros per bottle, most consumers in Europe, where distribution was primarily limited, felt this was still to expensive (bar the Italians, who I was told were snapping them up). One can only imagine how frustrating this must have been to Luca, who knew how good they were. The standouts from this year’s collection were undoubtedly those amazing 1970s Port Mourants, which are now probably close to priceless, if they can even be found. (And even the others are becoming grail quests – I saw an online listing in June 2018 for the Albion 1983, at close to two thousand euros).

When it came to releases, 2008 was a banner year for the company, when eight Demerara rums were issued at once. Yet widespread acceptance remained elusive: costing out at over a hundred euros per bottle, most consumers in Europe, where distribution was primarily limited, felt this was still to expensive (bar the Italians, who I was told were snapping them up). One can only imagine how frustrating this must have been to Luca, who knew how good they were. The standouts from this year’s collection were undoubtedly those amazing 1970s Port Mourants, which are now probably close to priceless, if they can even be found. (And even the others are becoming grail quests – I saw an online listing in June 2018 for the Albion 1983, at close to two thousand euros). Something interesting happened in 2010, overlooked by many, ignored by the rest. For the first time reviews of the Velier Demeraras start to appear in the blogosphere, and they were all from Serge Valentin of Whiskyfun. He had

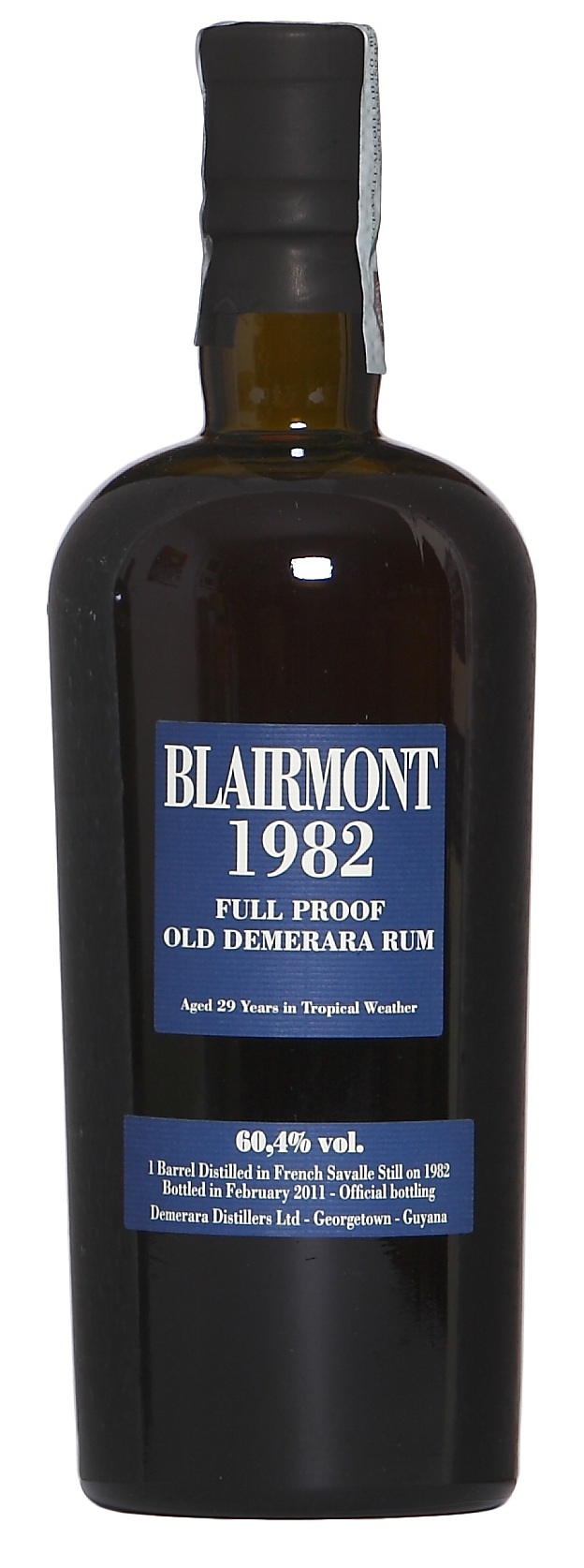

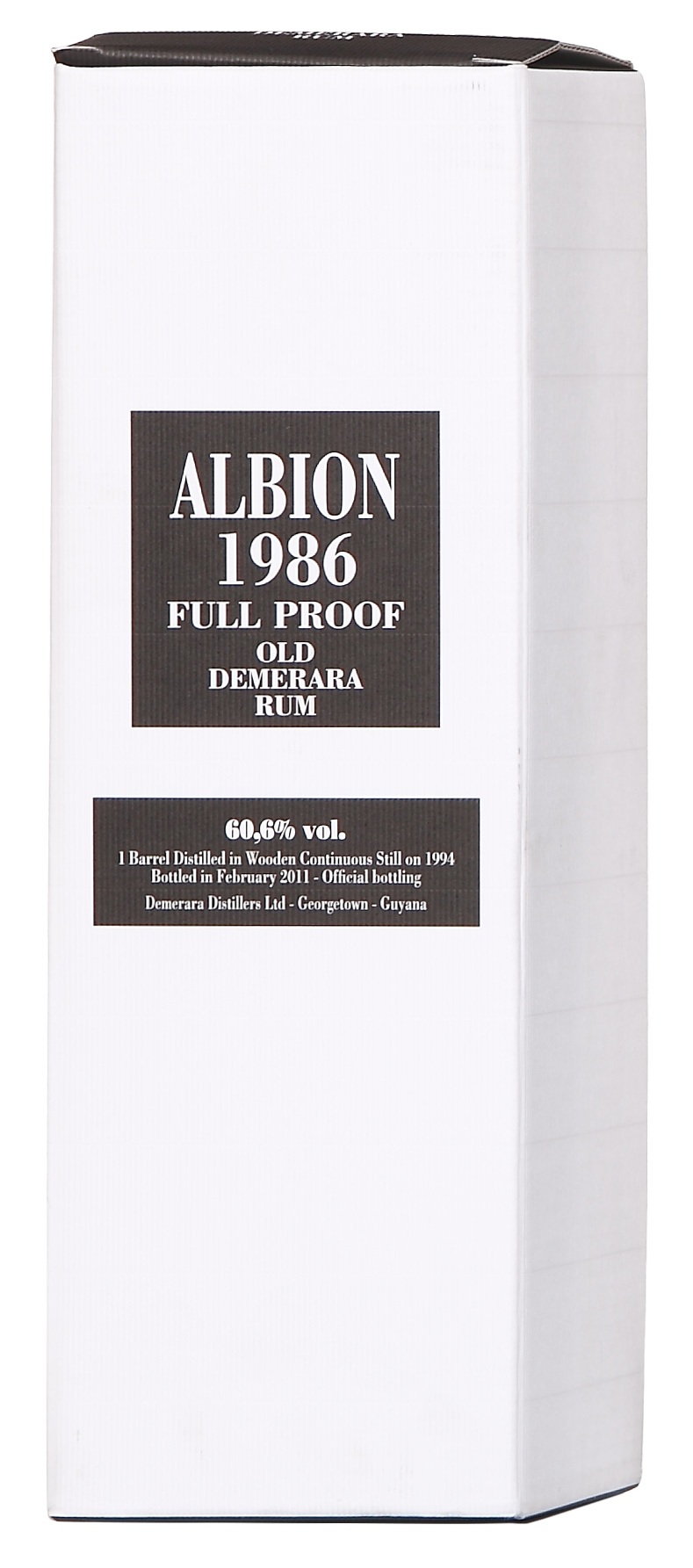

Something interesting happened in 2010, overlooked by many, ignored by the rest. For the first time reviews of the Velier Demeraras start to appear in the blogosphere, and they were all from Serge Valentin of Whiskyfun. He had  2011 was another skinny year, with only three rums being released, two of which were from Albion. Why DDL would sell off barrels of defunct distilleries like LBI, Blairmont or Albion is a curious window into their commercial mindset at the time – it’s possible that they simply didn’t see any margins in such niche products which might cost more to bring to market than they would sell for, though Velier clearly showed this was not so. Since Velier maintained a low profile outside Italy, they probably didn’t see such rums adding value to the DDL brand, and were okay letting them go.

2011 was another skinny year, with only three rums being released, two of which were from Albion. Why DDL would sell off barrels of defunct distilleries like LBI, Blairmont or Albion is a curious window into their commercial mindset at the time – it’s possible that they simply didn’t see any margins in such niche products which might cost more to bring to market than they would sell for, though Velier clearly showed this was not so. Since Velier maintained a low profile outside Italy, they probably didn’t see such rums adding value to the DDL brand, and were okay letting them go.

Nothing was issued in 2013 (the reasons remain obscure), and b

Nothing was issued in 2013 (the reasons remain obscure), and b

The rum world in the 1980s was a rather staid one, moving along very much as it had for years before. Major rum companies from around the Caribbean were issuing more or less the same rums they had been for decades – then as now, 40% ABV was practically a standard, age almost uniformly under ten years (if mentioned at all), and the market was full of familiar brands, similar recipes, incremental development, and with column still blends being the majority of sales.

The rum world in the 1980s was a rather staid one, moving along very much as it had for years before. Major rum companies from around the Caribbean were issuing more or less the same rums they had been for decades – then as now, 40% ABV was practically a standard, age almost uniformly under ten years (if mentioned at all), and the market was full of familiar brands, similar recipes, incremental development, and with column still blends being the majority of sales.

Aged rums made by primary producers from the pre-1990s eras were on the market, sure, and there was no shortage of them….but one had to look carefully for the specific trees in the forest (nowadays even more so when most exist in private collections or in memory alone).

Aged rums made by primary producers from the pre-1990s eras were on the market, sure, and there was no shortage of them….but one had to look carefully for the specific trees in the forest (nowadays even more so when most exist in private collections or in memory alone).  Anyway, much of the primary producers’ rum production went to Europe in bulk (a lot went to E&A Scheer, which was and remains one of the largest brokers buying rum stock in the world) and was then blended into European producers’ rums, of which there were many, none of which achieved any sort of lasting fame (unless it was the navy style of rum made by UK companies like Watsons for the local market). There were many small merchant bottlers, shops and back-street independents who released extremely limited and now-often-forgotten bottlings of aged expressions into the marketplace. And so the West Indian distilleries consolidated, shuttered, closed, changed focus, modernized, diversified, found new markets…and somehow the rum continued to flow.

Anyway, much of the primary producers’ rum production went to Europe in bulk (a lot went to E&A Scheer, which was and remains one of the largest brokers buying rum stock in the world) and was then blended into European producers’ rums, of which there were many, none of which achieved any sort of lasting fame (unless it was the navy style of rum made by UK companies like Watsons for the local market). There were many small merchant bottlers, shops and back-street independents who released extremely limited and now-often-forgotten bottlings of aged expressions into the marketplace. And so the West Indian distilleries consolidated, shuttered, closed, changed focus, modernized, diversified, found new markets…and somehow the rum continued to flow. What made the

What made the

A word should be spared for the work of the Martinique and Guadeloupe rum producers which don’t conform to the title of independents, but which also laid some of the groundwork for the renaissance of strong and singular rums that was about to take off. These small estate distilleries sold their rums primarily on the local market and exported to France through their own distribution arms there. Among all their lightly aged rums and blends and whites, they also and occasionally produced

A word should be spared for the work of the Martinique and Guadeloupe rum producers which don’t conform to the title of independents, but which also laid some of the groundwork for the renaissance of strong and singular rums that was about to take off. These small estate distilleries sold their rums primarily on the local market and exported to France through their own distribution arms there. Among all their lightly aged rums and blends and whites, they also and occasionally produced

But there was a sixth principle, not often stated, yet deeply held. And that was that food and drink should be as natural as possible, organic, free from the interferences of technology, fresh from the land. When one applies that to food it’s one thing, but few before him sought to apply the concept to rums (except perhaps out of necessity). He felt that rum should be bottled as it either came off the stills or out of the ageing barrel without further messing around. He may have known more than we did in those more innocent times, because although it is now common knowledge that many old favourites which came to the market in the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s were dosed with additives, back in the day there was a lot more trust going around between consumers and producers.

But there was a sixth principle, not often stated, yet deeply held. And that was that food and drink should be as natural as possible, organic, free from the interferences of technology, fresh from the land. When one applies that to food it’s one thing, but few before him sought to apply the concept to rums (except perhaps out of necessity). He felt that rum should be bottled as it either came off the stills or out of the ageing barrel without further messing around. He may have known more than we did in those more innocent times, because although it is now common knowledge that many old favourites which came to the market in the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s were dosed with additives, back in the day there was a lot more trust going around between consumers and producers.

He was still wrestling with whether this was a workable commercial concept when he found a stored 18 year old rum at Damoiseau in Guadeloupe which was so spectacular, that he released it at 60.3% ABV in 2002, crossing his fingers as he did so. The success of the

He was still wrestling with whether this was a workable commercial concept when he found a stored 18 year old rum at Damoiseau in Guadeloupe which was so spectacular, that he released it at 60.3% ABV in 2002, crossing his fingers as he did so. The success of the

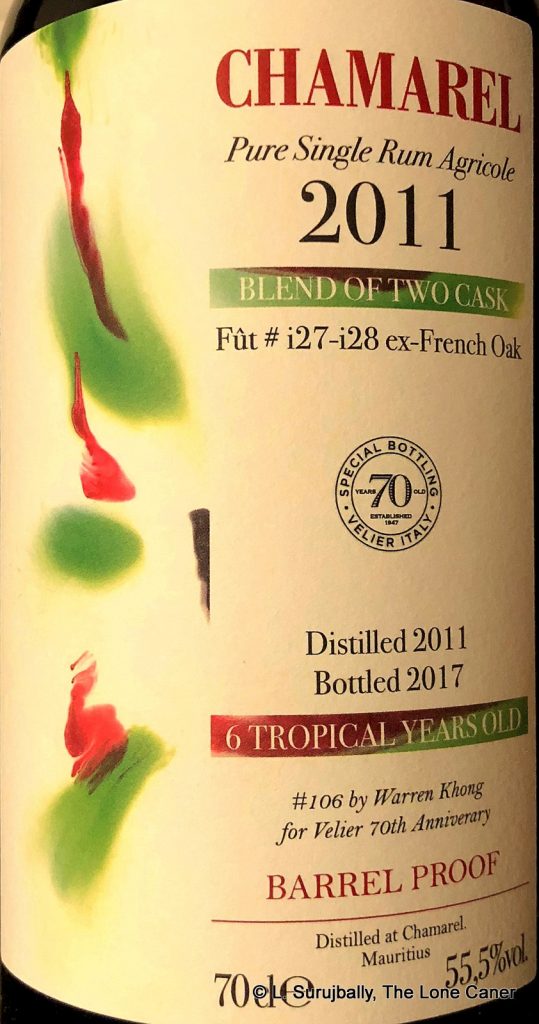

Chamarel Pure Single Rum Agricole 6 YO 2011-2017 55.5%

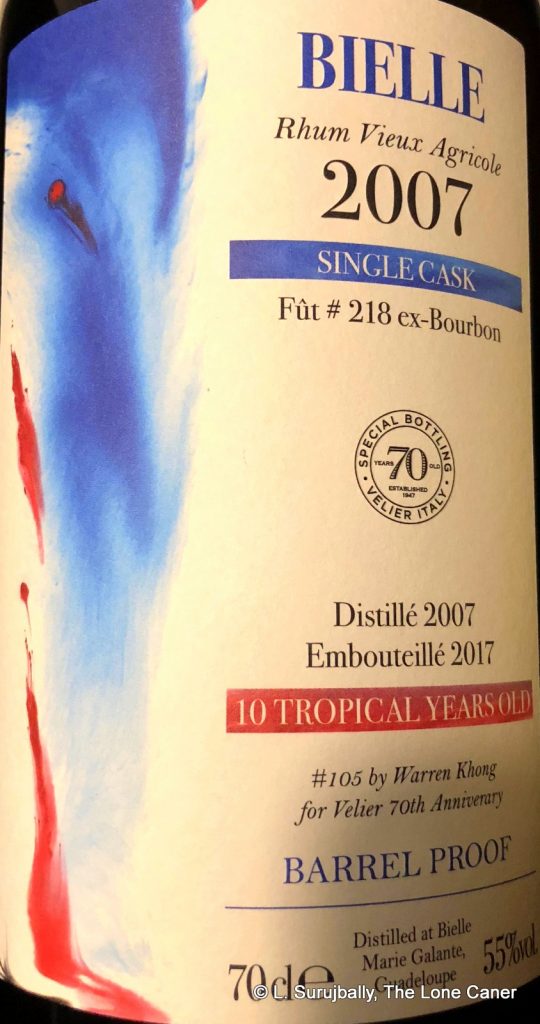

Chamarel Pure Single Rum Agricole 6 YO 2011-2017 55.5% Bielle Rhum Vieux Agricole 10 YO 2007-2017 55%

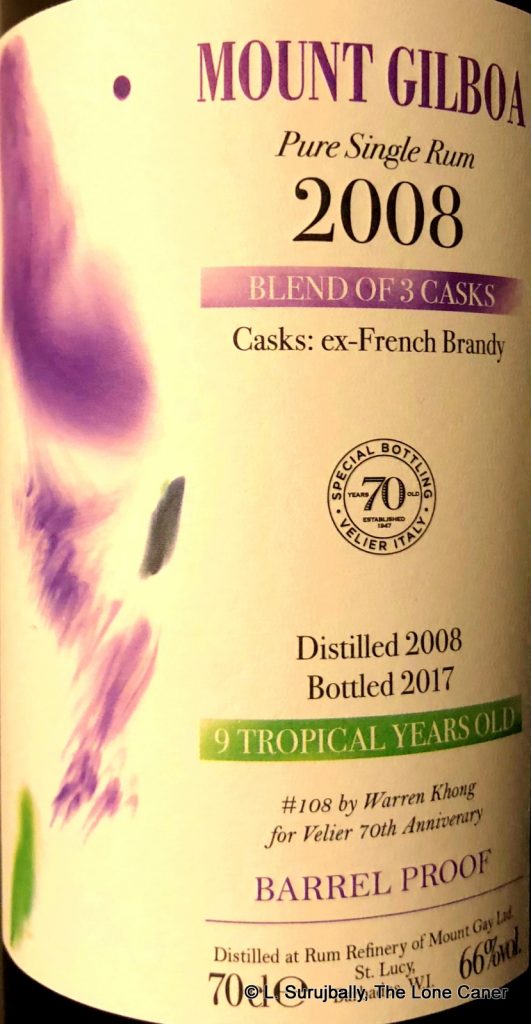

Bielle Rhum Vieux Agricole 10 YO 2007-2017 55% Mount Gilboa Pure Single Rum 9 YO 2008-2017 66%

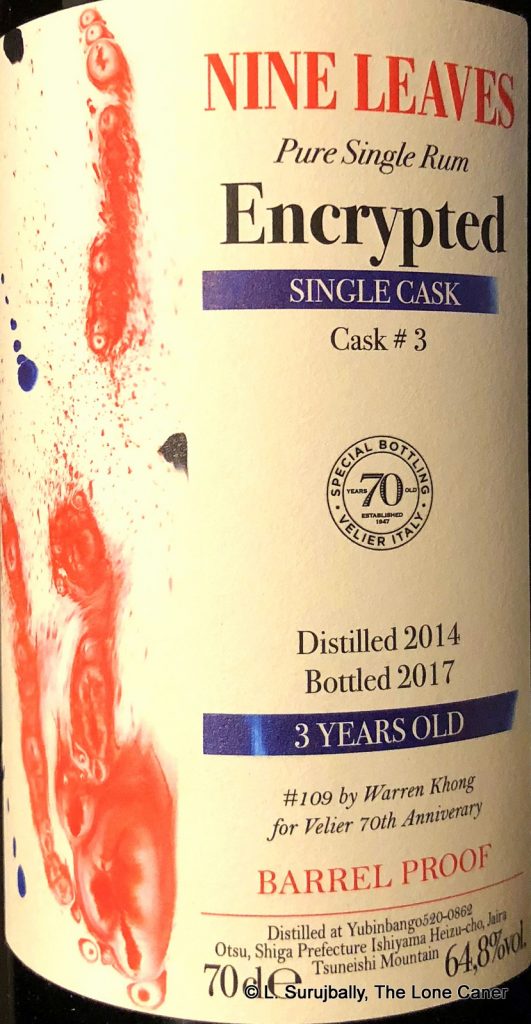

Mount Gilboa Pure Single Rum 9 YO 2008-2017 66% Nine Leaves Pure Single Rum “Encrypted” 3 YO 2014-2017 64.8%

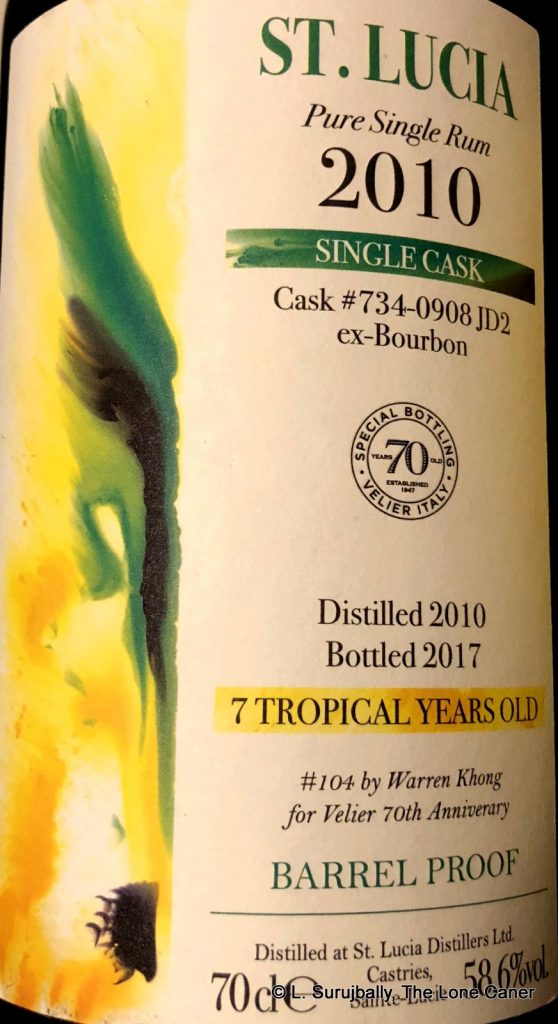

Nine Leaves Pure Single Rum “Encrypted” 3 YO 2014-2017 64.8% St. Lucia Pure Single Rum 7 YO 2010-2017 58.6%

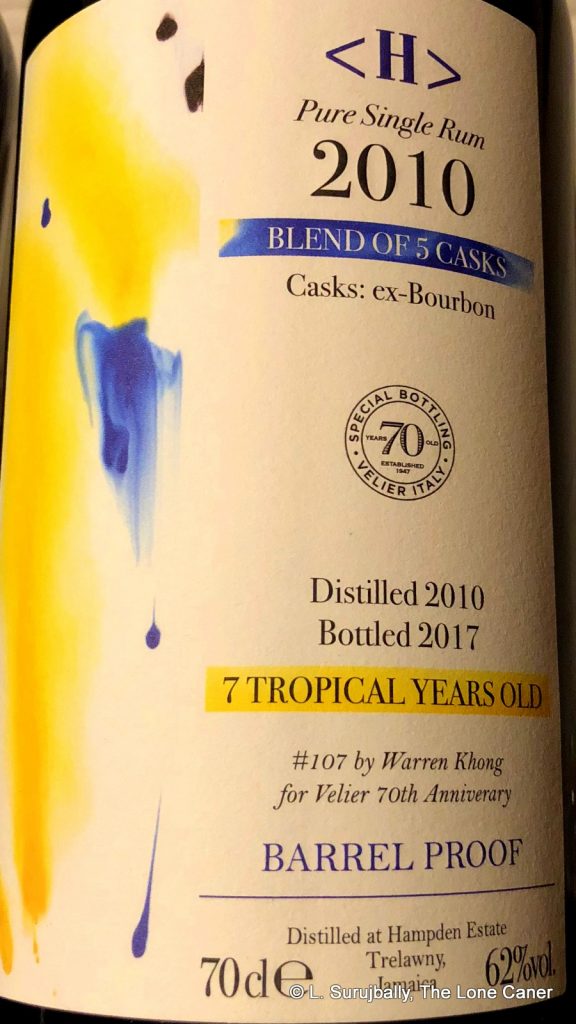

St. Lucia Pure Single Rum 7 YO 2010-2017 58.6% <H> Pure Single Rum 7 YO 2010-2017 62%

<H> Pure Single Rum 7 YO 2010-2017 62%

The nose begins with an astringent sort of dryness, redolent of burnt wood chips, pencil shavings, light rubber, citrus and even some pine aroma. It does get better once it’s left to itself for a while, calms down and isn’t quite as aggressive. It does pack more of a punch than the 25 YO, however, which may be a function of the disparity in ages – not all the edges of youth had yet been shaved away. Additional aromas of bitter chocolate, toffee, almonds and cinnamon start to come out, some fruitiness and vanilla, and even some tobacco leaves. Pretty nice, but some patience is required to appreciate it, I’d say.

The nose begins with an astringent sort of dryness, redolent of burnt wood chips, pencil shavings, light rubber, citrus and even some pine aroma. It does get better once it’s left to itself for a while, calms down and isn’t quite as aggressive. It does pack more of a punch than the 25 YO, however, which may be a function of the disparity in ages – not all the edges of youth had yet been shaved away. Additional aromas of bitter chocolate, toffee, almonds and cinnamon start to come out, some fruitiness and vanilla, and even some tobacco leaves. Pretty nice, but some patience is required to appreciate it, I’d say.