#479

We’re on something of a Jamaican rum kick for a week or two, because leaving aside Barbados, they’re the ones getting all the press, what with Worthy Park and Hampden now putting out the juice, Long Pond getting back in on the act, Monymusk and New Yarmouth lurking behind the scenes, and remember JB Charley with its interesting hooch? And of course behind them all, Appleton / J. Wray remains the mastodon of the island whose market share everyone wants a bite of.

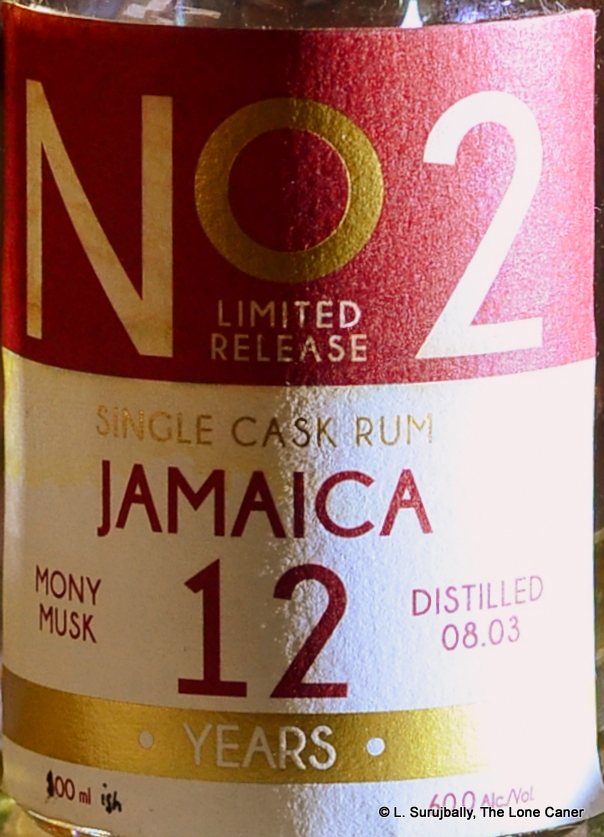

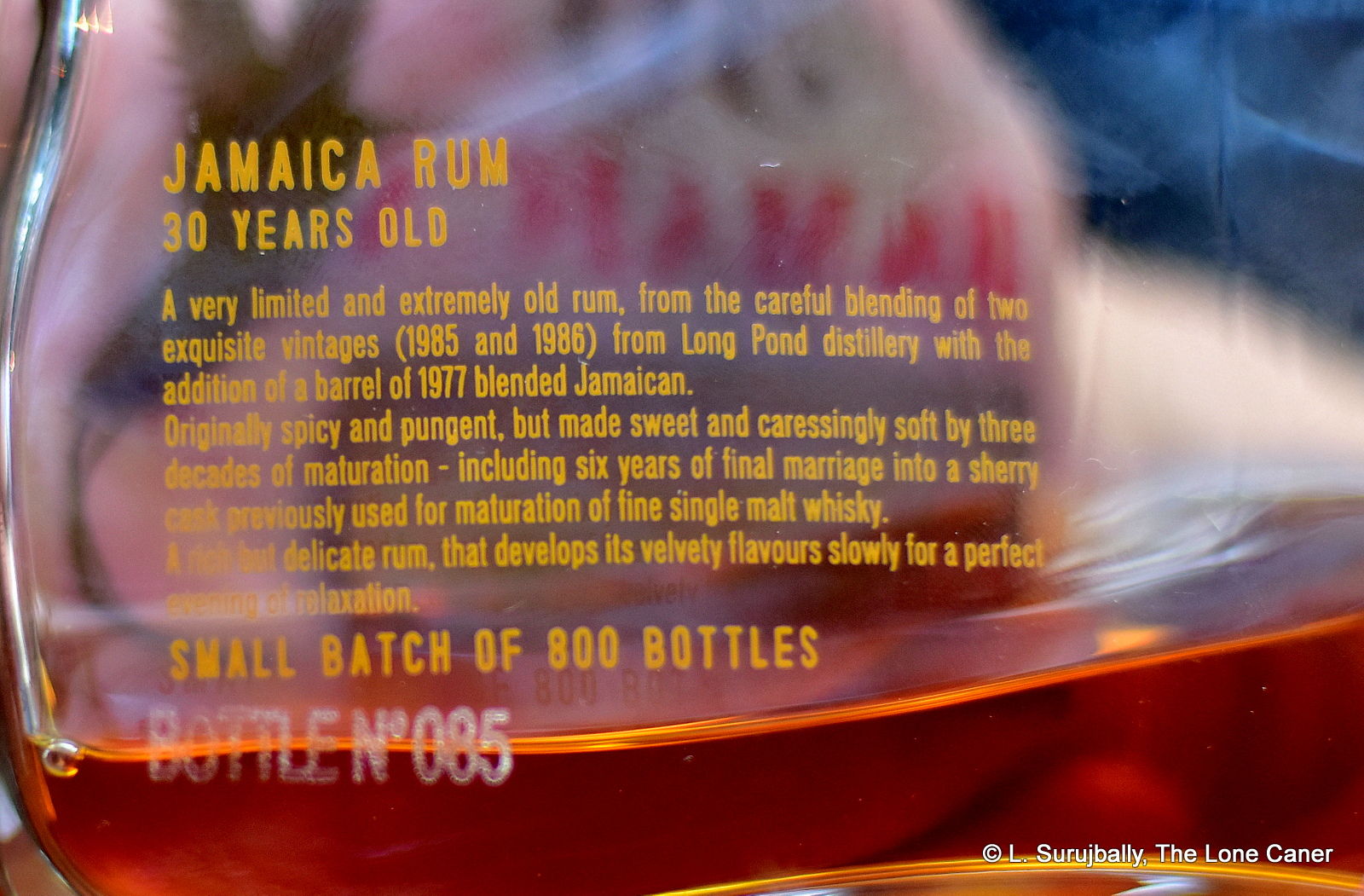

While Worthy Park’s three new 2017 pot still offerings are definitely worth a buy, and Hampden is putting some big footprints into the sands of the beach, I still have a thing for Long Pond myself – this comes directly from that famous and oh-so-tasty G&M 1941 58 year old I value so highly and share around so much. Alas, the only place one is going to get a Long Pond rum these days (until they reopen for business, for which many are waiting with bated and boozy breath) is from the independents, and Compagnie des Indes was there to satisfy the need: so far I think they have about twenty Jamaicans in the stable, of which three or four are from Long Pond and I think they’re all sourced from Scheer or the Main Rum Company in Europe. (Note: The best online background and historical data on Long Pond currently extant is on the site of that rabid Jamaican-loving rum-chum, the Cocktail Wonk, here and here).

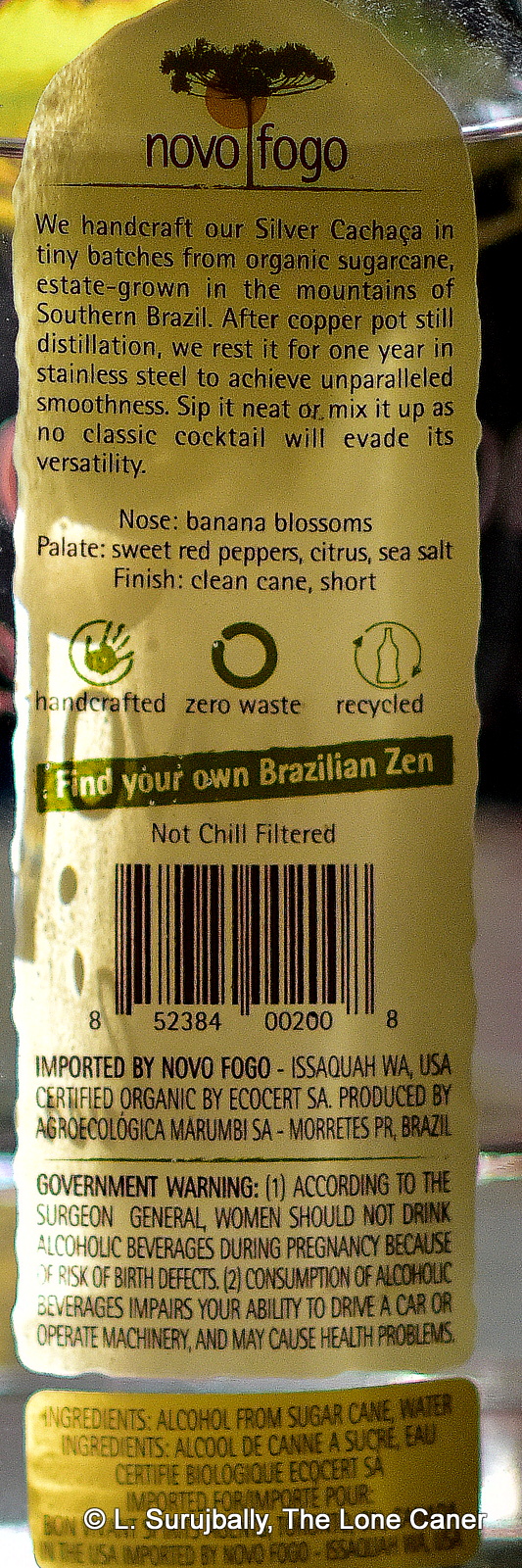

Moving on to tasting notes, I have to say that when the bottle was cracked and I took a hefty snootful of the pale yellow rum, I was amazed at the similarity to (and divergence from) the G&M 1941 that was over four times older – there was that same wax and turpentine opening salvo which was augmented by phenols, rubber and some vague, musky Indian spices. Honey and brine, olives, a few sharp red peppers (gone quickly), and a generous serving of the famous funk, crisp fruits and light flowers. It was well assembled, just a shade vague, as if not entirely sure what it wanted to be.

Never mind. The palate was where the action was. Although the bottling at 44% ABV was not entirely enough to bring out all the subtleties, there was more than enough to keep the glass filled several times as I leaned back and took my time sampling it over an hour or so. It began soft and warm with bananas, honey, whipped cream, a little salt caramel, and a little rye bread, aromatic wood chips (I hesitate to say cedar, but it was close). Then the ester brass band came marching on through, providing the counterpoint – citrus, tart apples, cider, green grapes, and was that a flirt of cumin and curry I sensed? It came together in a nice tantara of a long, warm and spicy finish that wasn’t particularly original, just tried to sum up the experience by re-presenting the main themes – light fruity notes, some salt, olives and caramel, and a final leaf-blade of lemon peel holding it all together.

Long Pond is known for its high ester count of its rums and that over-the-top funky flavour profile, so what I tasted, tamed as it was by the relatively unassertive proof point, came as no surprise and was a pleasant reminder of how very well properly-made, lovingly-aged Jamaican rums can be. This standard proof rum was issued for the general market with 384 bottles and as far as I know there’s no cask strength or “Danish market” edition floating around. But that’s not really a problem, since that makes it something everyone can appreciate, not just the A-types who cut cask strength rums with cask strength whisky. Whatever you preference in these matters, the CdI Long Pond 12 remains a tasty, low key Jamaican that isn’t trying to rip your face off and pour fire down you throat, just present the estery, funky Jamaican rum in its best light…which this it does with delicacy, finesse, and no problems at all. It’s a really good twelve year old rum.

(85/100)

Other notes