Tintin is becoming a worldwide phenomenon (again) as a result of Jackson & Spielberg’s 2011 film adaptation (long overdue, in my opinion, and thank the Lord they didn’t do it in live action). Me, I’ve been a fan since my childhood, and have had the entire collection at several points in my life (they keep getting pinched by young friends and relatives, who are drawn to the adventures and Herge’s signature drawing style). I wanted to do a review of one of his adventures, even though, to purists, I imagine that it is not necessarily a book per se, but a comic. Well, maybe, but as literary works in their own right, comics have their own pride of place, and we cannot readily ignore them. And who is to say the primarily visual medium of Tintin is in some way less because of it?

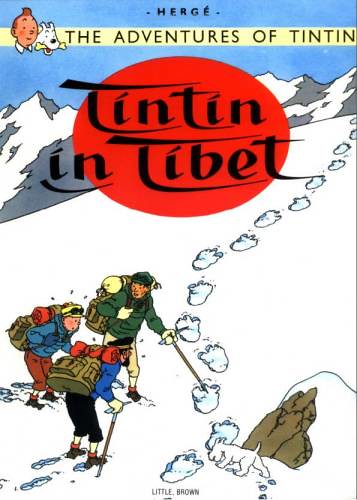

Tintin in Tibet is to my mind one of the most straightforward and artistically rendered comic strip of the series, and possesses one of the strongest, simplest story lines. Tintin, after reading about a plane crash in Tibet, has a dream that his young Chinese friend Chang (first encountered in the much more politically aware The Blue Lotus created in 1934/1935) is still alive, and resolves to find him. Drawn in a minimalist style with much empty space and clear renderings of the harsh Himalayan mountains, the story follows Tintin and his two companions to the crash site, to the search in the forbiddingly desolate terrain and there isn’t a moment when you aren’t eagerly turning the pages to see what’s next. Here, for a wonder, supporting characters are minimal – no Calculus, no twins, no Castafiore, no Wagg, Abdullah, Rastapopulous, Alan or any villain. And indeed, none is needed – the story and its clarity of drawing are as as devoid of excess as a haiku. And, it might be added, as strong.

Herge created Tibet as an anodyne to his personal problems of the time: he was in love with a young woman in his office and did not know how to end his relationship with his wife of the past three decades; he had been having nightmares of white (a cartoonist’s writer’s block, maybe?) and wanted to put together something simpler, something starker. After some batting around of ideas he came up with this one, and it ended up being serialized in Le Journal de Tintin in 1958, and published in book form in 1960. For what it’s worth, his nightmares ceased, he chose the path of divorce, and Tibet is considered one of his finest works.

Tintin is a character thought up by the Belgian author in the 1920s. Officially his profession is that of a reporter, though he really looks too young for the role – he’s usually referred to as a “boy reporter” — and doesn’t do much writing throughout the series of his adventures: he often seems more like a boy scout than a professional of any kind. His distinctive shock of upturned hair and his white fox-terrier Snowy first appeared in 1929 when Tintin in the Land of the Soviets appeared. By the time Tintin in Tibet was released thirty years later, the character and his colorful supporting cast was already known the world over…and least recognized in that other great stable of comic book characters, the USA. He had never had a girlfriend, was still the same age, seemed to have no real source of income, was still able to jet off to have adventures in strange places at the drop of a hat…and remains popular to this day (and no, I won’t get into the gay motifs many have commented on).

There are several aspects to the perennial attraction of Tintin’s adventures. First and foremost is the artwork. Herge championed a drawing style from which American comics had long diverged (and continue to diverge) – that of clear lines which presented extraordinary detail in a single frame, without ever actually overcrowding it. Called ligne claire, the characteristics of such artwork are an absence of shading and hatching, which provide all elements within the frame equal importance, defined only by relative perspective. Too, while the characters in the frame are somewhat cartoonish, the background detail is highly realistic. It’s almost tailor-made to capture the young mind, and when you think about it, the early Superman and Batman comics from the thirties also displayed this kind of style, though with less background detailing and gradually increasing shadow and contrast.

Secondly, there is sly wit and humour throughout the entire series, embodied in vivid and memorable characters. The detectives Thompson and Thomson (they are specifically noted as not being twins on the official website), and their “to be precise” gags (note their mustaches, the only way they can be told apart). Cuthbert Calculus, the boffin who is hard of hearing and has that bizarre combination of brilliance and naivetee (and endearingly literal approach to conversation – Sheldon Cooper is his modern-day incarnation) that so characterizes the comic scientific cliché. The cynical (but loveable) near-alcoholic whisky-loving, oath-uttering Captain Haddock, whose name the scatter-brained opera singer Bianca Castafiore can never quite remember. Snowy himself, and his little side comments. And all those other secondary characters who popped up here and there throughout the decades in one adventure or the other: Jolyon Wagg, Chang, General Alcazar, Abdullah and his doting father, Sir Francis Haddock, Red Rackham, Rastapopulous Rex, Olivera de Figuera, Zorrino. It’s a well-populated tapestry and aficionados know them all by heart. Tintin and his sidekicks may be a bit one-dimensional, but there’s no question that the richness of the storytelling and artwork carry you along past such complaints.

Those who are familiar with Tintin will recognize his similarity to a Boy’s Own story – a rip-snorting adventure yarn that takes you along with its young protagonist to exotic locales in order to solve dastardly crimes and make the world a safer place. It’s really not meant to be taken too seriously. Still, for its time it was quite a bit ahead of American comics, and displayed a respect for other cultures which came about as a result of much controversy over previous editions of Tintin’s adventures (most notably Tintin in the Congo) which had embarrassed and affected Herge quite deeply. Herge had often been seen as a collaborator with the Nazis in the post-war years, even though his work of the time was staunchly and deliberately apolitical – probably these experiences and the outcry over negative portrayals of indigenous people made him more sensitive to such perceptions in both his later work and the subsequent revisions of his earlier comic strips.

Tintin’s adventures encompass sci-fi, mystery, adventure, exploration, mysticism, horror, technology, bigotry and humour. I think everyone who likes Tintin has a favourite, not least because of the broadness of its themes. I like them all, and some less than others, but it’s a mark of its strength that the whole canon remains one of those pieces of my literate life which left such a mark that I keep buying and re-buying the series, even as I pass my own sell-by date. Hopefully, one day, my own boy and his in turn, will appreciate it as much as I do.